Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Defining "Mental Health"?

|

Mental Health and the Brain:

|

|

Our first session and resulting on-line forum discussion set a context for our continuing conversation based on institutional characterizations of the state of mental health care and our own experiences with it. Among a number of issues that raised is the question of what exactly one means by "mental health." We'll explore that question further this week. To get started

- Write one paragraph that gives, as best you can at the moment, what you think is a clear and useful definition of "mental health" and post it as a reply to the question posed in the on-line forum below. Don't worry about its being "right." You will have ample opportunity to suggest revisions to your definition (and other peoples') during the rest of the semester.

- Do a quick first time reading of the three papers linked to below. Do this AFTER you have written and posted your one paragraph definition. The upcoming session will consider the extent to which the three readings do or do not provide reasons to change existing definitions of "mental health" and point directions in which such revisions might perhaps be usefully made. Your thoughts about the papers needn't be posted now; you should include them in the forum below as part of our continuing on-line discussion after the Monday session.

Readings for this week

- A Critical Analysis of the Scientific Model of Health

- Culture as Disability

- Models of Mental Health: A Critique and a Prospectus

The Problem

- "the mental health delivery system is fragmented and in disarray" ... New Freedom Commission on Mental Health

- "Stigma erodes confidence that mental disorders are real, treatable health conditions" ... National Alliance on Mental Illness

- "Policy makers, insurance companies, health and labour policies, and the public at large - all discriminate between physical and mental problems." ... World Health Organization

- "In order to get rid of the stigma behind mental illness, it's important to establish that it is indeed a medical disease with biological causes." ... Paul Bloch

- "Many of us feel that mental illness should be treated as physical illness, and that treating it as such will destigmatize mental illness. Along those lines of thinking it seems perfectly reasonable to search for a cure, just like scientist would search for a cure for physical illness." ... jrieders

- "for it to be construed as a disease locates it within the individual, as something to be "fixed" and ignores the cultural context, which ... can be a significant influence in defining/addressing mental phenomena" .... LauraC

- "Even if all disorders (mental and physical) could theoretically be boiled down to some physiological cause, there is no reason to believe that people would not stigmatize them anymore. If we do want to reduce the stigmatism surrounding mental illness, it’s not enough to just prove a medical/biological cause. " ... ryan g

- "Many mental health problems, who knows what percentage, are caused by life style choices." ... mbayer

- "it depersonalizes the illness experience and may lead to an increased sense of alienation from one’s own mind (body)" ... Sophie F

- "If a person, by medical standards, has a mental illness, but they themselves are happy and don't feel that their mental health is compromised, do they still have a mental illness?" ... kmanning

- "Is “mental health” an endpoint or an ongoing project of sorts?" ... Sophie F

- "All this disagreement about the idea of soul, self, mind and body as being seperate entities makes the study of mental health a fractured and incongruous practice. To which part do we owe the most loyalty and which part needs to be cured?" ... akerle

- "I think it's really hard to listen to and believe all of this talk about treatment for mental illnesses when we don't even really know what a mental illness is." ... Karen Ginsburg

- "This inability to recognize mental illness astonished me. Has our society reached such a point as we are no loger capable of not only helping but recognizing those that need it the most? ... llamprou

Defining "mental health": a solution?

- " A mental illness is a state of mind (be it depressed, manic, etc) that disables one from functioning in a given society" ... Paul Bloch

- "Mental Health is a sense of general acceptance and satisfaction with the mental states one is experiencing." ... jrlewis

- "Everything I come up with seems to have too many exceptions to be a "definition."" ... Ljones

- "I'm wary of any definition that references societal norms" ... ryan g

- "Society has to define 'normal' parametres because there is no other way but who are we to judge what makes people happy and what is normal? Certain behaviours may be harmful to society but that doesn't make them abnormal. We just don't like them so we classify them as such" .... akerle

- "It can't be all black and white, all the time, either "mental health" or "mental illness."" ... merry2e

- "I think it has more to do with the context and the specific person than any all-encompassing definition." ... Paige Sayer

- "Mental health isn't necessarily about being happy" ... Riki

- "the popular definitions of "mental health" ... are based almost exclusively on what I would not consider to be "mental" activities at all, but rather behavior ... Is behavior a true gauge of mental health? Or is it just the only one we really care about? ... sgibbs

- "Perhaps one's mental health is entirely unique to every individual and there is no general definition." ... llamprou

- "Much of our discussion seems to be moving in a direction which would suggest that what defines "health" or a "good/normal human specimen" is going to be left up to individual choice. This would mean that an individual human person gets to decide what is good for them and they can say nothing about what is good for their neighbor ... I feel I need to voice a contrary opinion ... We may not ever know with certainty what ought is implied, but there certainly is some ought ... " ... mbayer

- "I think we are actually, truly downplaying mental illness if we decide that mental health is basically subjective. " ... ysilverman

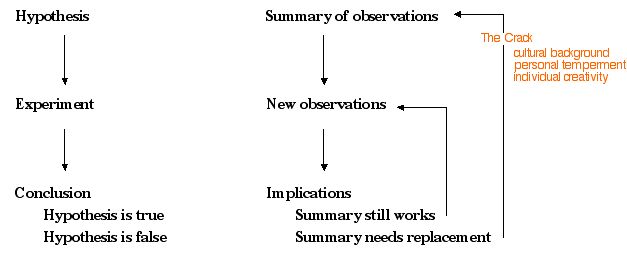

Is the "medical model" a good take off point for thinking about/trying to define "mental health"?

Contexts in which the medical model evolved/is most effective:

- relatively simple cause/effects relationships (eg. the "germ theory")

- near universal agreement on what constitutes a "problem" to be fixed

- strong correlations between cause/symptom/treatment which in turns makes isolation and categorization ("diagnosis") productive

- presumption that observations by external observers ("objective") are more useful/reliable than internal ("subjective") experiences

- usefulness of transferring personal authority to "expert" other

"Mental health" phenomena

|

"“What this is saying is that all treatments work, at least for some people, and have serious risks for others,” he said. “It’s a trial-and-error process” to match people with the right medication." ... NYTimes, 15 Sept 2008 "Fifteen years ago his condition would probably not have been called bipolar disorder, and some doctors might hesitate to diagnose it in him even now, preferring other labels that more directly address James’s rage and aggression: Oppositional Defiant Disorder (O.D.D.) or Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (A.D.H.D.) — both of which have been applied to James as well." NY Times Magazine, 14 Sept 2008 |

- complex cause/effect relationships

- cultural and individual variation, both as normative factors and as causes

- weak correlations among causes/symptoms/treatments

- individual/subjective factors play prominent roles

- diminished personal authority may itself be a problem

In search of some alternative starting points/models for thinking about "mental health" (and perhaps a new definition of it?)

Child rearing

Education

- One never gets it "right," but one can always get it less wrong

- Wherever one is at any given time, one has the resources to get it less wrong

- What is important is not what one can't do but what one can do

- Getting it less wrong is best done by borrowing from/contributing to others getting it less wrong in their own ways

- Individuals and cultures influence each other

- "Mental health" = the capacity to grow/change/evolve/create and recreate meaning for onself and others?

Does this help with the stigma problem? With the culture problem? With other problems? What problems does it not help with? What new problems does it create? Put your thoughts from/following today's discussion in the on-line forum below.

Comments

The definition is not really a good definition

This post has taken me a while to get up here and a large part of the reason is because the definition that was decided upon last Monday does not sit well with me at all. I don't believe that only the mentally healthy are able to grow/evolve/create and recreate, often times the those that do these things most are those in serious need of mental help.

I may be a little ahead of the curve but I just finished reading the book that I picked to do my report on, it is in the reading list and titled "Divided Minds". The novel tells a story of two twins sisters of which one has schitzophrenia. Both sisters attended and graduated Magna Cum Laude from Brown University, both were able to get into prestigious medical schools. Does this sould like either one of these ladies had any problems with our definition of mental health?

As one reads this book however it becomes clear that neither of the two are actually mentally healthy. Both sisters are suffereing either physiologically or emotionally. I would like to think that when I suffered a serious depression in high school that I was still able to grow/evolve/create and recreate. I think that this definition is in many ways greatly flawed. I think mental health is far more complicated than the ability to do these things.

Unfortunately I do not really have a definition to propose but this definition certainly does not cover all the bases. I think that perhaps what mental health is cannot be defined, and I know that Paul thinks that this is a cop out. Maybe the correct way to assess mental health is in levels, similar to Maslow's Heirarchy of Needs. Is it possible that there is a very basic concept of what consists of mental health and tiers that than can build from that basis.

Really what I want to point out is that "our" definition is flawed and I don't think that any progression can be made from such a flawed notion of what mental health is. Those are just my thoughts and I know it has taken a while to put them up here, but I kept starting this blog trying to defend the definition when really I completely disagree with it.

mental health: right and wrong

What 'destigmatizes' illness...?

I feel as though society stigmatizes cancer and AIDS because no one completely understands the complexities of these illnesses. Instead, people just associate them with "devious" behavior - like linking AIDS with unprotected sex or syringe sharing. If people were to see AIDS as a sydrome and not as its metaphores, then I think the stigma would vanish...

...So while I now think that mental health/illness is more complicated than the illness model, my original point was that if people saw mental illness as an illness and not as weak character or bad behavior or any other associations, the the stigmas would go away.

Defninition of Mental Health

Definition of Mental Health:

It took me a really long time to get to post, but I reallywanted to give the issue of Mental Health, Health and Illness a great deal ofthought before I committed anything to writing.

I want to start of by saying that I really began by feelinga great deal of sympathy to Paul’s position. Having studied psychology, Ibelieve that the DSM is really a very bad way to think about Mental Health andIllness. Furthermore, it seems there are a lot of places in the field of mentalhealth that are poorly served by the medical model. I think Paul made thosepoints quite well. Yet I was still somewhat uneasy with the idea that there isnot such thing as illness when related to mental health.

I spent some time talking to a couple different people inthe field and also re-reading some old articles and these are my conclusionsfor the time being.

First I think that its easy to pick on the illness model, becauseit’s actually a limited model even in medicine. As Paul lays out the medicalmodel, the lack of complexity seems to apply well to a broken arm but not to acase of diabetes or heart disease. Diabetes or heart disease, seem tocorrespond better to Paul’s description of mental illness. They have complex causes and I think theywould best be seen through more complex lenses than medicine currently tends totreat them.

There are ofcourse many holistic approaches that have beenbecoming more popular that deal with illness in a broader context and give “cures”that involve lifestyle on a whole.

So to a certain extent I think the illness model is a bit ofa paper tiger.

But I also had another critique of the model that came outof talking with my father who is a psychologist that works with schizophrenics. I asked my father whether he thoughtthat it helped schizophrenics think about their condition as an illness. Hethought that it was actually quite helpful and did not need to be stigmatizing.

He pointed out that to begin with as a society we tend toview mental health in much more stigmatizing ways than as an illness. For most of our recent history mental illness(or difference) has either been criminalized, treated as demonic or dismissedas just crazy. In contrast to these, the idea of illness is actually a verycompassionate and meaningful advance. Wedon’t stigmatize people for having cancer and we are less likely to stigmatizethem for mental illness.

The Illness model can also help people think about theirconditions from a disease management perspective. A diabetic knows that theyneed to monitor their diet and educate themselves about the feelings that goalong with different levels of blood sugar. In the same way a schizophrenic caneducate themselves about brain differences that accompany schizophrenia and thedifferent ways that this differences can affect their lives.

Having said all of that I feel that the problems of thedisease model extend throughout the field of mental health. For example, is itreally helpful for us to think about ADD from a disease perspective. Here it really seems that we are stretchingthe boundaries of disease into very murky waters indeed.

After a lot of thought, my conclusion is:

1. The disease model is usefulbut limited for both mental health and physical health. All health and lack ofhealth has the potential to be very complex. We should always honor and seek tounderstand diversity as it effects human health.

2. The division betweenphysical and mental is a very problematic one. All mental phenomena have aphysical correlate and vice versa. Back pain (and pain in general) is a mentalphenomena. We must remember this both in the treatment of mental health andphysical health.

3. We need to think deeplyabout a good definition of health and illness that deals with both on aholisitic level, without stigmatizing, but still opening up our ability toreally help each other.

Mental "illness": from spirits to criminality to stigma to ... ?

Being personal too

Hi merry2e. Although I have shown the hand of my professional life- I too have struggled with the personal. My brother- never satisfactorily diagnosed (had paranoid schizophrenic; schizo-affective disorder; bi-polar and the ever favorite dually diagnosed, died over the summer after ingesting too much cocaine and Fentenyl. Was he lacking "conscience"? Sometimes. Was he too sensitive and in touch with (painful) reality? Sometimes. Did he qualify for a diagnosis that should have meant helpful services might have been his due- much of the time. Yet, the reality (notice the little 'r') is that few who really struggle with severe mental disorder (a term with which I'm a bit more comfortable than "illness") often get even less in terms of care than those who are the "worried well" who want to self- actualize. I still maintain that offer of a relationship in which to engage and try out one's stories in various ways ( and I agree with Anne's implication that they are stories and Paul's that they are changable and not always consistent) is still the ideal way for allowing "treatment" of the disconnect people struggling with difference from the norm often experience. So it almost returns us to the notion that "mental illness" had much more to do with disconnect from the (social) norms than anything else- yet for those of us who have felt the rush into the pit of darkness and apathy, there seems to be more than just social norms. So what does a truly biopsychosocial definition, or an otherwise multifactorial one begin to look like?

"more than social norms"

Certainly my personal experience as well. Which isn't to say that social norms are irrelevant (they're not; I'm convinced that my own episodes of depression, for example, would have been distinctly less unpleasant if I'd been living in a different culture), but that there is indeed "something more" involved.

For Judie's "professional life," see "Another periodic participant"

website

http://www.thinkbody.co.uk/index.html

Some interesting articles for those of you interested in body therapy/mind-body connection...

I am torn once again along with some others!

mental health: "blunt and personal"

An obsession with meaning

is very interesting, and reminds us that a definition of mental health as self-understanding and self-evolution is really just an ideal and a norm itself. Just because it involves the evolution of a person towards an undefined goal as opposed to some ideal, does not mean it doesn't leave some people being deficient and some not, in ways that perhaps wont always be in agreement with who thinks they are mentally healthy and who not.

Also, to respond to your thoughts on "being realistic" akerle, I think part of the problem with the mental health world right now is that people started being realistic before having a concrete or unified understanding of what they were being realistic about - prescribing drugs and treatments and writing policies before anyone had any idea what the problem even really was. I too get frustrated with overly abstract discussions about topics that need immediate action, but hey, we're in a seminar, why not start as abstractly as we can and work our way down?

Mental Health...and Reality

I've just finished Jeanette Winterson's novel, Lighthousekeeping, which gives another perspective on the question of whether mental health can be measured in terms of an "awareness of reality":

The psychiatrist…asked me why I had not sought help sooner.

“I don’t need help…I can dress myself, make toast, make love, make money, make sense”….

“Do you keep a diary?”

“I have a collection of silver notebooks.”

“Are they consistent?…do you keep one record of your life, or several? Do you feel you have more than one life perhaps?”

“Of course I do. I would be impossible to tell one single story.”

“Perhaps you should try.”

[and then, from a later session:]

“An obsession with meaning, at the expense of the ordinary shape of life,

might be understood as psychosis….”

“I do not accept that life has an ordinary shape….How would you define psychosis?”

"...out of touch with reality."

Since then, I have been trying to find out what reality is, so that I can touch it.

re "reality" (and mental health)

Am myself reading The Echo Maker by Richard Powers, which perhaps ups the ante a bit. The novel revolves around a man who has had an auto accident and comes out of a coma certain that his sister, who has been caring for him, is an imposter (an instance of "Capgras syndrome;" see one of the background readings for this coming week). That in turn begins to raise serious questions both for the sister and for a visiting neurologist (an Oliver Sacks character) about whether each of them actually is or is not who they thought they were. Who's "out of touch with reality"?

And those in turn bring to mind a couple of interesting movies I've seen recently. At the end of the Coen Brothers latest, Burn After Reading, one character asks "What have we learned?" to which the reply is "Not to do that again." The scene ends with the follow up question "What did we do?" and the response "I don't know." Couple that perhaps with the tag line from Charlie Wilson's War, "we'll see," and you get .... reality?

One more article to question some of the assertions

This focus on the belief that having a diagnosis or Connecting the biological aspects of mental health issues to functioning somehow leads to less stigmatization and more self- and other- understanding may be based on an incorrect assumption. In one of the most recent Social Science & Medicine journals, an article by Jason Schnittker ("An uncertain revolution: Why the rise of a genetic model of mental illness has not increased tolerance" (2008; 1370-1381)lays waste to this notion. In the spirit of getting it less wrong, foundational assumptions must be questioned.

just being realistic here

In reading all of this discussion about mental health/illness and concepts of abstract thought I'm forced to wonder something- what does this all really mean for the population at large? I am all for a world in which we cater to each individual's desire to become more self- actualised but HOW can this happen? What can we actually do to change minds and hearts about mental illness (or whatever we want to call it). At the end of the day...abstract thought is just that: thought. Unless, however, it somehow manifests itself in the real world. This disussion may broaden our minds but can we use these conclusions in a concrete way?

As for my ideas on how to do this- well I can't say that i understand any better than the next person. Perhaps we need to change policy, change the education system but something needs to change s we can see the effects f THIS conversation on the real world.

As I am posting rather late,

more thoughts on "diagnosis"

If we allow a diagnosis to take the form of more of a description of a person's mental state (as opposed to healthy/ill) and remove value judgments like we have been discussing, I think a diagnosis, and yes I still want to use that particular term, can be extremely useful. If someone is seeking help because they are no longer able to understand themselves and how they can change themselves, a diagnosis of the form I suggest - one that helps a person recognize their behaviors and explain and understand what societal/mental forces might be causing them -might be extremely helpful in restoring a person's ability to understand themselves. The help-giver must of course be very careful not to apply value judgments, but so long as they are, I think someone seeking help for mental health troubles of our new definition can certainly benefit from a diagnosis. We just need to expand what a diagnosis can involve.

Therapeutic Tales

Telling tales

Hello Prof Dalke,

I know for my life telling my stories in therapy, etc., have been helpful for releasing past hurts, etc., and I have learned that there is a place and a time to tell them. This reminds me of a story I wrote last Fall semester that hit on some personal issues...and then I felt as though I could not write for months later. Was this helpful? I can see now that it was though the timing was a bit off. And it may just be that a text that one find's very hard to digest is reassuring for another. I used to obsessively read books on concentration camps when I was a child/teen. The more detail, the better. And, though these stories I read were horrible...they taught me of courage and bravery and many other concepts that I needed to learn.

Just a thought.

Meredith

Some concepts that may help

As someone has practiced clinically for 20+ years and who has partnered in the journey of self-awareness/ movement toward a healthier place/attempts to feel better, I have some concepts to offer to the discussion.

First, a number of the posts reference the idea of whether the individual is discomforted by their experience of their mental/ emotional/ interactional state. In the old Freudian terms, this was referred to as having a condition which is ego dystonic, as opposed to ego syntonic where the person feels perfectly fine just the way they are (think Axis II personality disorders). Now, what does it do to your various definitional attempts to think of people who few like because they do not fit into their social milieu well, but who view everyone else as having the problem?

Another thing to grapple with: Freud once said that mental health was the ability to live, love and work productively- what does that one mean for people who are unable to fulfill one of those capacities due to a physical condition rather than a mental/ emotional one?

There is an article on "The social construction of Normality" by Sophie Freud as well as various critiques of mental health models by Thomas Szasz that indicate, to varying intensities, that what gets deemed as mental health is really just an ability to fit into one's environment (with anything revealing a lack of fit deemed as less healthy). Indeed, the change of homosexuality from viewed as diagnosable to a varied lifestyle is often used as an example of the mutability of definitions of mental health and subsequent diagnoses.

As a clinical social worker, I have found that very little about definitions and diagnoses has relevance to the work I am doing with clients. Granted, I am seldom working with people experiencing "SMI" (severe mental illness) although I am often working with people who are experiencing intense emotions and huge destabilizing life changes. Many of these folks could be "diagnosable" with DSM criteria (and some have to be for insurance purposes), yet I seldom if ever find that this provides anything useful for our work together. Invariably, finding out the client's story, their interpretation of it, the ways they believe this defines who they are, and the areas of pain that exist within the story, all provide a much more useful template for our work together. Notably, that work, unlike medical practice, involves formation of a relationship where working together in authentic, warm and perspective- building ways is what moves the work. Again, unlike medical practice, it is not a matter of the therapist giving advice, directly intervening upon the being of the client, nor functioning UPON the client in anyway- merely continually being willing to be in relationship in a way that supports the client when they feel destabilized and destabilizes and stretches the client when they feel self righteous.

Fodder for the mill....

The tyranny of diagnosis

I found this article in the NYTimes (i don't think it's already been posted, but if so I apologize!) about how doctors are treating only illnesses and not whole patients.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/19/health/chen9-18.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

It's so in line with our discussion as to almost not be new and exciting anymore, but one thing it does illuminate is that this problem of doctors only treating what is wrong or deficient - and not treating a person as a whole person - is not unique to mental health at all.

As I mentioned in class when Prof Grobstein was presenting the medical model of cause - symptom - treatment, I dont think the mental health model needs to be different from this basic backbone of the "medical model". What does need to happen is that we expand the definition of cause to be more than biological. If a person presents with a symptom that is mentally unhealthy (by whatever standard of mental health we conclusively decide upon) the person who is helping them must then look to what could have caused this to be the case. Maybe it's social, maybe it's biological, maybe it's existential, etc. Then, a treatment plan is decided upon, to restore this person to mental healthiness (to being able to understand their current condition and how to change it, or whatever other definition we would like). This treatment plan might involve talk therapy, it might involve drugs, it might involve meditation. Most importantly, it must involve the patient's continuing involvement in self-assessing and assisting their helper is assessing them.

Like Ryan, I am struggling with coming up with step #2 of our mental health definition - how to use the definition to ACT. Somehow, the theory I outline above currently gives me comfort.

What I am not sure of yet though, is what exactly the ultimate "good" in mental health is. Prof grobstein said it is understanding oneself and how to change oneself. In my first definition that I posted I said it was being in a state where one is always seeking happiness/wellness (I believe all humans by nature strive to achieve a greater sense of happiness than that which they presently posses). I like how professor grobstein's definition does not involve an ideal, BUT i also think there can be many different kinds of definitions that dont involve ideals, and do involve the evolving of the patient. I would be very interested in discussing other possibilities for the ultimate "good" of mental health.

Mental health practice and its "ultimate good"?

The brain?

Katie, I agree ... I think

Katie, I agree ... I think that is part of why I felt like our discussion in class almost devolved into semantics. Because whatever we call it, I feel like there can be a very qualitative difference between periods of mental wellness and mental unrest. I can believe that there are people who feel differently minded -- but I also think a lot of people who suffer revel in being diagnosed, in being told that their unhappiness/anxiety/loss of control is not an inherent part of their personality or life or mind, that there are varieties of methods available to work towards alleviating what might reasonably be called symptoms.

As Laura very accurately pointed out above, the brain is an organ, if a complicated one. Yes, all brain illnesses lie on a continuum. And maybe there is no clear demarcation between mental health and mental illness ... But many people who hit "emotional bumps" in the road can say that their outlook on life is *totally* different at some points than it is at others. I am very willing to agree that diagnoses, as they stand, can be as harmful as helpful, but I also completely feel that times of emotional aberration are much like periods of illness. Certainly many people don't feel more emotionally able during those periods of time ...

I hate to personalise this discussion, and at the end of the day I think most of us have gone through periods during which, for whatever reason, we feel less emotionally well. At the same time, I would feel remiss in not acknowledging that at points I have felt very emotionally different -- and that at these points I feel significantly less, and not more, myself. In fact, I feel kind of ... sick.

If someone undergoes a transient period of intense mental pain, different than anything they have experienced prior, is prescribed medication, and after 2-3 months feels markedly better in *every* way, I don't know that simply an emotional evolution has taken place. To me, it still sounds like they were episodically ill ...

Well spoken...er, written.

Well spoken...er, written.

I recall a client of mine, a woman in her early 20s, who had been diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive disorder. She also had mood swings, depression, a learning disability, a history of suicidal "gestures" and severe anger management problems. It was abundantly clear to me from our first session that she was very invested in her diagnoses, and in fact, had adopted them as a significant part of her identity. I asked her to describe her OCD rituals to me, and then I asked her if they were "getting in the way of her life." She said "no, not really", and I said, "Ok, let me know if and when they do." She then asked "Do you think I'm a freak?" I said, "nope." Then I moved on. It never came up again in session.

True, not everything needs to be fixed, at least not in the way we may think it does...and "normal" doesn't necessarily mean, um, "normal." :)

Like you, I have also gone through times of emotional "sickness", and have often described it as "not feeling like myself" (this is a common complaint of individuals with depression). As I have said elsewhere in this forum, I believe most individuals to have some sense of what normal is for them...I just recalled another Gestalt term, which is homeostasis...the desire of a system to reach a state of equillibrium. Might this be included in a definition of "mental health"?

Sarah

From "mental" to "emotional" health: behaving and feeling

I am not entirely ready to

I am not entirely ready to completely divorce the medical model of health/illness from mental health. I don't think we can accept that the brain is something special and should not be treated in the same way the body is treated. If my arm is broken a doctor fixes it, if my stomach cells can't create a certain enzyme that is need for digestion then a doctor gives me a pill to supplement the enzyme, if my brain is missing an enzyme that keeps me from remembering what happened 5 minutes ago then my doctor should give me a pill too. If something is broken, it should be recognized as such. This does not mean that everything needs to be fixed just because we know that it is broken. Health is just one of many goods in human life that must be ordered and subordinated to one another.

If I had a mutation that gave me an extra arm, I would have to acknowledge that the mutation is abnormal. But I would not need to say it is necessarily a bad thing that needed to be fixed. The arm might enable me to do a lot of new and useful things, but it would also result in my alienation from much of society because having 3 arms is abnormal. I think this is the line of reasoning that is being used to suggest that we should not think of mental illness as an illness at all.

I agree with that assessment on some level. But, there comes a time when these "differences" will effect wether or not someone can live a distinctively human life and I think this is the case more often than not with mental differences. If, through some difference in brain composition and function, a person looses the potency to: engage in community, to acknowledge and try to improve their own understanding of reality, or any other activity that is distinctly human then I think there is reason for saying that person is broken. Having three arms doesn't prevent me from living a human life but being unable to engage reality does.

Side note on reality: I agree entirely with what Grobstein said about human knowledge being partial and perspectival, but the fact that we say we try to get things less wrong implies (correctly I believe) that there is some objective reality to which we are all trying to conform our conceptions to. Each cultural norm is imply the sum of the most popular understandings of reality in a given place. That is why people are so fond of saying that one is not better than the other, simply because it is difficult to tell which one is better than the other. However, rest assured that one understanding of reality is better than another, although I don't know for sure which one it is. I do think it (the best approximation of reality) is mine, and you do think it is yours or else we wouldn't think what we do!

Prof, Grobstein could you elaborate what you mean by a capacity to create meaning?

A fresh perspective...

I'm going to go out on a limb and say that after last Monday's discussion many of us are feeling a bit lost for words...

(Example... Me in my last post: "My God... !! We can't say anything about anything. Nothing is for real. There is no healthy/ill, good/bad, wrong/right, up/down... Where do we go from here?")

Ok, maybe it's just me. But with that in mind, thank you for bringing some new perspectives to the table, Marty.

I want to dive a bit deeper into some of your ideas... It is suggested that If something is broken, it should be fixed. Someone who is unable to live a life that is distinctively human is broken, and therefore, should be fixed.

This concept of a distinctively human life is interesting to think about. What criteria constitute a distinctively human life? Three were mentioned: 1. able to engage reality 2. participate in community 3. acknowledge and improve understanding of reality. Beyond this, I feel it is left up to us to fill in the blanks intuitively.

However, this maybe isn't so intuitive... as Sophie suggested. Who is to say what a distinctively human life is? The doctors? The politicians? Spiritual leaders? Each and every individual? The task seems overwhelming to say the least.

With this in mind, can we ever really define if a person is broken?

And speaking of broken... if we are defining a broken/not broken dichotomy, I would say that a three armed man is broken. However, it's suggested that we can acknowledge his difference without making value-judgements. Why can't we do this for "mentally broken" people?

Finally, there was also the idea that "getting it less wrong" implied an objective reality. I don't have much to say about that besides for I am slightly envious of your conviction. However, I am not sure that trying to get it less wrong suggests an objective reality. Here's a quote from Dr. G's paper:

"My answer to these challenges is not only that one can indeed do science in the absence of the concepts of truth and reality, but, whatever one (the I-function?) may think, that is in fact, operationally, the way science is done. "Progress" in science is not measured by increasing closeness to "truth" or to the "real"'. It can't be, because neither "truth" nor the "real" is a known location against which proximity can be measured. Progress in science has instead always been (and can't but be) measured in terms of distance from ignorance. Science proceeds not by proving "truth" or "reality" but rather by disproving falsity, not by painting the "right" picture but by painting a picture "less wrong" than prior pictures. And that, rather than either "objectivity" or some other privileged access to "reality" is in fact the basis of the demonstrable power of science.

This is, of course, simply another way of describing "pragmatic multiplism", the notion that inquiry proceeds by assuming that, at any given time, there exist at least two admissible interpretations of available observations, the one currently used and the different one that will, by accounting for available observations as well as some new ones, replace it."

Getting it less wrong without an objective reality

"If something is broken, it

I think it's important to realize that some people don't want to seek help (even if society deems it necessary) because they feel as though aspects of their mental condition allow them to do or create things that they otherwise could not have done. For instance, some people with bipolar disorder don't like treatment because they like what work their mania gives rise to and they feel more creative during their manic episodes. There are many great works of art that probably wouldn't exist if the artists had sought medical help -- Van Gogh, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, Kurt Cobain. That isn't necessarily to say that everyone who suffers from a mental "illness" should abstain from getting help, just that positive things <i>can</i> result from dark times. Sometimes mental "illnesses" should be embraced instead of looked down upon.

more on creativity and "mental health"

From a recent senior thesis

I found Riki's comment on

I found Riki's comment on certain mental illness and their effect on the creative performance to be very interesting.

However, I also believe that creative talent is not something necessarily linked to a disability, but rather an innate quality that may manifest itself in some individuals more than in others. The cure for disabilities should not, in fact, be something that suppresses a natural talent or a particular quality, but rather something to help this talent or quality to evolve.

Especially in light of the type of society in which we live today, where mental illnesses are somewhat frowned upon, we cannot just appreciate the disabilities of a person only when that proves to be productive in artistic terms, and ignore the individuals in all other contexts. Thus, a cure for mental illnesses would not be aimed at changing the person itself, thereby eliminating a particular creative talent, but, on the contrary, at helping him/her flourish in all fields of his/her social life.

I agree that not everything

I agree that not everything that is broken needs to be fixed. I personally feel that there is way to much unnecessary "fixing" that occurs now in our "prozac nation".

But just gotta point out that the artists you mention all committed suicide, three of them before any real treatments existed for their conditions. Yes, these people were talented, creative, amazing, and very, very unhappy. I'd like to venture that if they could talk they might have something to say about the "costs" of their creativity. I think our culture has created a romantic view of the "mad genius", that in actuality may not be so great. Kay Redfield Jamison's "An Unquiet Mind" addresses this very issue with great feeling and eloquence.

Just a thought.

Sarah

I definitely think that our

I guess some of it stems

I guess some of it stems down to whether or not you think that creativity is more valuable than a life lived without bipolar disorder...

In fact, studies have shown that creativity and bipolar disorder are strongly correlated to one another. But they have also shown that family members of people with bipolar disorder who do not present as bipolar also have enhanced creativity. So what if bipolar is on the continuum of creativity, but past the point of mental health on that continuum? All four of the people you mentioned committed suicide before the age of 50.

It is true the mania can produce extreme highs, but depression can produce equally extreme lows -- and as the "mental state" takes its course, it becomes harder and harder to produce *anything* during those often increasingly intense periods of mania.

There are some interesting dicussions on this topic on the web both on serendip (/exchange/node/1726 -- Dr. Grobstein has just invited this conversation to find its way over here) and off (http://ideaflow.corante.com/archives/2005/11/10/bipolar_children_more_creative_than_other_kids.php) ... And I'm sure other places as well. And you're right -- some people in both locations find the illness debilitating, while others say they avoid treatment and revel in the mania.

Still, even if there are benefits, the lows can be extremely low. A brilliant friend of mine, who had been hospitalised multiple times, talked of frequent suicidal impulses and attempts during mania (though this person didn't consider herself to be suicidal, and certainly didn't want to die). She certainly doesn't feel she has benefited, regardless of her bursts of creativity.

This page (http://www.pendulum.org/bpnews/archive/001653.html) quotes a study that says people diagnosed with bipolar who take lithium are 8 times less likely to commit suicide than people who are off lithium. Just because there are some positives to something, if it really does kill people, does that make it not an illness?

Bipolar disorder, autism, life, and death

Thanks for a useful set of links. Kaye Redfield Jamison in her An Unquiet Mind, says

There's an interesting parallel here to Temple Grandin, writing about her own experiences with autism. Yes, there are pontential problems but also potential virtues. Maybe the key here is to stop thinking about bi-polar disorder or autism (or .... etc) as in themselves "illnesses" and start thinking instead about what potentials (positive and negative) are associated with particular kinds of human variation and how to help people nake the most of those?

That, of course, sounds a lot like life in general, for everyone. Along those lines, maybe its worth also keeping in mind that life itself "really does kill people"?

" Along those lines, maybe

" Along those lines, maybe its worth also keeping in mind that life itself "really does kill people"?"

Touche. Though, I want to say that having thought about it for a long time (certainly longer than this term thus far), I do not think that a healthy (physically or mentally) individual should want/attempt to kill themselves. Others are welcome to disagree.

And, along those lines, there isn't necessarily physical illness, either? Or, something that hastens death isn't an illness, but a change in states? Of course we will all be felled at some point or another, but that doesn't mean that ailments are to be ignored, I don't think. Half the fun of life is evading death ... Or maybe more than half, even.

Still unsure, but...

I’m not sure what Professor Grobstein means by “create” meaning. However, inherent in your statements is that you have ascribed meaning to certain behaviors and that meaning is somewhat arbitrary. An arm is broken when it is broken, but how can we asess what range of human behaviors constitutes “broken” in the same way? Especially, when values are not universal, to which you aluded. A broken arm remains so whether in Bryn Mawr, Alaska or… However, behaviors are not so easily reduced to a dichotomy: broken vs. normal. I’m also uncertain about your use of “distinctively human life.” I’m not sure it is reasonable to impose limits upon what makes us human based on behavior, variable and subject to myriad external factors. We may view someone, for example, on the high-functioning continuum of autism to be “sick,” but as we saw in class, the same “pathology” could be ascribed to you or me if a different system of values is employed. In my opinion, that which makes us “distinctively human” cannot be confined to a finite range of behaviors.

I don’t think my “approximation” of reality is better than your approximation of reality, but mine, though ever-changing, works for me.

mental health and "making meaning"

I'm still fumbling...

Several years ago, I read a book by James Gordon, a psychiatrist, called Manifesto for a New Medicine. I found an interview with him, http://www.healthy.net/scr/interview.asp?ID=225, in which he discusses the limitations of the healthy/sick paradigm. He says, “I was first attracted because I was made uncomfortable by conventional psychiatric treatment. I was working with psychotic people, who seemed not to be sick in the way that people with gall bladder disease or people with heart disease or cancer are sick, yet they were treated as if they were physically ill. They were put in pajamas, and given large doses of medication. I didn?t understand it. It seemed like they had certain difficulties; they were sometimes harder to understand or more erratic than most so-called normal people, but they certainly didn?t seem sick.

So I began to question the whole medical model. That is, that there was a specific disease entity that people had, and a specific kind of pharmacological or surgical treatment for them. I began to question whether for these psychotic people, if we regarded their experience as essentially a human experience, if we created a healing environment in which they would be fully respected, could change the nature of their illness? So I was questioning the whole notion of fixed diagnostic categories.”

JRLewis mentioned that discarding the health/illness paradigm seemed to draw an artificial distinction between mind and body. While, I agree the distinction is artificial, on the contrary, I think re-shaping the dialogue about mental states, along a continuum, with language that is less extreme (healthy vs. ill) creates an environment in which more voices can be heard in the conversation about these mental states and if they are to be shaped or changed, it is not, necessarily, with an end in mind. In my opinion, this is not, simply, an issue of semantics, but an issue of redefining the terrain of what we know as mental illness; and, in so doing, recognize that perhaps there is no destination where mental well-being is concerned, but rather it is the journey that is significant. In the Bipolar Puzzle article from this past Sunday, linked somewhere above, mentioned two instances in which the diagnosis of bipolar in children had been changed, and both were due to the influence of physicians. My question is, in the realm of “mental health” are physicians the people who determine normative behavior?

Ian Hacking, who works in the field of Philosophy of Science, has written widely on the phenomenon he calls “making people up.” (http://foucaultblog.wordpress.com/2007/06/15/ian-hacking-on-making-up-people/). The thrust of his argument is that the more we study, classify and define people, the better able we are to “control, help, change or emulate…” He then points out that all of our studying, probing and doctoring actually changes people, for we do not exist in a vacuum. In this view, people are who and what they may be; this is not an argument against medicine or against comprehensive treatment for those who present in a mental health practitioner’s office with troubling behavioral patterns. The point, in my mind, is to understand that just as health/illness do not exist unto themselves, without the coalescing of myriad factors (experience, cultural background, age, etc.), nor can we reduce behavior, the workings of the mind to a singular cause and effect. Moreover, in so doing, we create "illness" and categories of people, such as the outmoded category of hysteria, amongst others. To borrow Sarah’s analogy from above, two peoples’ kidneys, whether healthy or not, are a lot more similar than the mental states of those same two people, though their brains may also structurally be similar. Again, biology is essential and to borrow James Gordon’s words, we should attempt to work with the “transformative” powers of biology, but not see a biomedical framework as the "answer" to a “problem.”

"what of people who do

I think a lot of stigma is due to the fact that many people are subjected to labeling, for instance, as being bipolar, and that is how people define them. They aren't seen as another person just like me or you, but rather as a bipolar person. It can be very alienating, which is terrible because people, not just those who are mentally "ill", need to know that they are not alone in their experiences. It's just part of the human condition to search for others so as not to feel so alone.

Also, I think it's interesting to listen to the words people use when describing someone who has a mental "illness". Do they suffer from something, do they have something, is it who they are? I use all of them without giving it much thought...

Labels

Rikki -

An excellent point. You are absolutely right that a diagnosis can be very devastating for the individual. Very early in my therapeutic internship, I learned to refer to clients in a specific way: e.g. not "a bipolar". "a borderline", "a schizophrenic", but rather "a person with (or "diagnosed with") bipolar disorder", "a personal with borderline personality disorder", etc, for just that reason.

It's also why I believe strongly in group therapy. Like you said, these experiences can be very alienating, and it can be very helpful to interact with others who are going through something similar, be it depression, panic attacks, or auditory hallucinations.

Most therapists I know (the good ones, anyway) tend to stay away from the term "suffer from", and try to refer instead to specific symptoms or diagnoses. e.g., "the client experiences/reports periods of delusional thinking..." or simply, "diagnosed with...".

In session, I have also used the verb "struggle", since that is often what I see people doing in response to their symptoms...

Sarah

Making up & Changing people

"He then points out that all of our studying, probing and doctoring actually changes people, for we do not exist in a vacuum."

I like the idea of "making people up" and the concept that individual people together influence their culture/society but that activity can in turn change the individuals and so on back and forth. I like concrete examples and one (maybe) that came to mind... why do people who hear voices, those with schizophrenia or what have you, often have hallucinations of a negative nature? One suggestion is that historically most people who heard voices did not neccessarily have negative/threatening/violent ones, and that cultural judgements about hearing voices has biased hallucinations.

"what of people who do benefit, personally, from a paradigm that does empower them to see "illness" as being something they "have" and not who they are?"

I don't think a particular "model" of anything has to be entirely rejected, if there are aspects of it that "work" I think they can be incorporated into a new "model". As Professor Gibbs said in class, many of her clients like thinking about their "condition" as biologically based and that helps them acheive whatever their goals in therapy may be. But it still begs the question, would those people who are empowered by thinking in terms of "illness" feel disempowered to begin with in a new/better model of mental health? If yes, then feeling empowered by thinking in terms of "illness" would seem appropriate. But maybe they could end up feeling more empowered by a new/better model? I think a goal for a new model of mental health would be for all to feel as empowered as possible in the first place and then act from there. I think maybe we have to examine what purpose thinking of something as an illness, not a part of who they are, serves. For my personal experiences of depression, thinking it of an "illness" has been helpful in so far that it releases some of the responsibility and allowed me to look at my experience more objectively and in a way understand it better. On the other hand, thinking of it as an "illness" makes me feel powerless and feel like it has "happened to" me.

So, I guess my conclusion for right now is that because we've acknowledged that individuals are so diverse, on a number of parameters, we can't get caught up in trying to make too broad of generalizations, as there will always seem to be exceptions and unique contexts to consider.

Illness

Laura -

Your comments about your personal experience of the term "illness" made me think about another group of clients I have dealt with...substance abusers and addicts. Many therapeutic approaches to treating these clients shun the use of the term "illness" for just the reason you state - it can lead to feelings of powerlessness and reluctance to accept personal responsibility. To some extent I agree, but I don't think using the term illness necessarily leds to complacency - I certainly have not observed that in my clients with schizophrenia, for example.

By analogy, if I get ill with a cold, I might feel like it "happened" to me, but I might also admit that maybe I've been working too hard, and I'm still gonna go buy some cough syrup!

Sarah

I agree with Sophie that the

I also agree that we cannot draw a distinction between mind and body. In one of my psychology courses, we spent time talking about in other parts of the world where psychological differences are not talked about or considered serious (I wish I could remember where specifically we were speaking about) psychosomatic illnesses are a lot more common.

On a lighter note...

Yona sent me this video and it seemed a little too similar to what we are discussing to not post.

http://streetbonersandtvcarnage.com/blog/street-carnage-films-presents-sophie-can-walk/

Plus, it will make you smile.

Thanks for sharing this! It

In defense of mental illness

I've been thinking about the conversation from Monday, and keep coming back to the same few "thought bytes":

- To perhaps expand on jrlewis' comments (I'm so sorry I don't remember your non-screen name!), the brain is an organ, part of a larger organ system that is the CNS and PNS. Sure, it's complicated, and we don't understand it as well as, say, the kidney (which is pretty amazing, too), but it's comprised of the same stuff. Why, then, is difficult to imagine that this organ can become "diseased"?

Individuals with schizophrenia show dementia, changes in personality, acting out, and progressive loss of brain volume throughout their lives. Individuals with Alzheimer's and Huntington's Disease show the same symptomologies. All three conditions typically show an adult onset, are thought to arise through a combination of genetic and environmental factors, and are currently without cure. Is any one of these more of a "disease state" than the others? Anyone want to make the argument that Alzheimer's is not an illness?

- I don't think that the term "mental illness" can be considered in a vacuum. Rather, it exists in relation to "mental health." "Illness" implies that there was once health, and now there is not. It also implies that the sate of health can be reacquired. The people I know with schizophrenia remember a time when they were "mentally healthy", and they mourn its loss. They also hope for its return, and are eager to learn of advances in research and treatment.

I can certainly see the argument that individuals on the more higher-functioning end of the autism spectrum may not remember a time when their mental state was any different (given the early onset), and thus may understandably take exception with the "illness" label. However, it is my experience that most people with debilitating mental conditions, be it depression or schizophrenia, long to return to their own unique state of mental "health", and have little interest in convincing themselves or others that their condition represents a "different type of normal."

I also have a problem with using words like "growth", "evolve" and even "change" in a definition of mental health. As a therapist, I try to stay away from these sorts of terms, because I feel them to be somewhat condescending, implying that one is "lacking" something or is not "complete" the way they are. This attitude also stems from my adoption of the Gestalt therapeutic approach (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gestalt_therapy), which essentially rejects the explicit goal of change (becoming what one is not) and replaces it with the goals of awareness and integration (becoming what one is).

Ok, I'm shutting up now.

Gestalt theory

Sarah, thank you for bringing up Gestalt theory (which I have no understanding of beyond what wikipedia just told me, but sounds very interesting!). Perhaps wikipedia's summary is not exactly correct, but from what it says, it actually appears to be very in line with (my understanding of) professor Grobstein's definition of mental health.

To quote the all-powerful wikipedia on Gestalt therapy:

"The client learns to become aware of what they are doing psychologically and how they can change it. By becoming aware of and transforming their process they develop self acceptance and the ability to experience more in the "now" without so much interference from baggage of the past. The objective of Gestalt therapy, in addition to helping the client overcome symptoms, is to enable him or her to become more fully and creatively alive and to be free from the blocks and unfinished issues that may diminish optimum satisfaction, fulfillment, and growth."

The end goal of Gestaltian therapy thus seems to very much be saying what I interpret Professor Grobstein to be defining mental health as: the ability to perceive of one's own condition and how one can change it.

(I am unsure whether I think one needs to only be aware of how one's situation could be changed, or needs to actually be changing it, in order to be mentally healthy - thoughts?)

Anyway, while I do really like the self-understanding/evolution theory of mental health, and I'd be happy to call it the first step one takes when deciding if someone is "mentally healthy", I worry that in many cases asking this question wont get us very far. Is a child with bi-polar disorder who is threatening the lives of his family members one moment and crying in their laps the next impaired in being able to understand his own condition and how to change it? YES. Now what?

I think the challenge put forth in Culture as Disability, and by the self-understanding/evolution definition of mental health is a very worthy cause that must be addressed, but I also think if we put forth ALL our efforts towards changing cultural norms so there is no longer "mental illness" and "mental deficiencies", we are going to not give "help" to a lot of people who may need it in a more "traditional" mental illness kind of way.

(I apologize for my overuse of quotation marks. I am wary of all adjectives and nouns after our discussion Monday night. And also for not really giving any conclusions in this post - the ideas are still unclear in my mind!)

Gestalt and change

Laura and K (sorry I do not know your full name...) -

Great stuff!

Yes! You are absolutely right in interpreting that the purpose of awareness is change...that's perfectly in line with one of the main tenets of Gestalt theory, the Paradoxical Theory of Change, described below by Arnold Beisser http://www.gestalt.org/arnie.htm:

"I will call it the paradoxical theory of change, for reasons that shall become obvious. Briefly stated, it is this: that change occurs when one becomes what he is, not when he tries to become what he is not. Change does not take place through a coercive attempt by the individual or by another person to change him, but it does take place if one takes the time and effort to be what he is -- to be fully invested in his current positions. By rejecting the role of change agent, we make meaningful and orderly change possible.

The Gestalt therapist rejects the role of "changer," for his strategy is to encourage, even insist, that the patient be where and what he is. He believes change does not take place by "trying," coercion, or persuasion, or by insight, interpretation, or any other such means. Rather, change can occur when the patient abandons, at least for the moment, what he would like to become and attempts to be what he is. The premise is that one must stand in one place in order to have firm footing to move and that it is difficult or impossible to move without that footing.

The person seeking change by coming to therapy is in conflict with at least two warring intrapsychic factions. He is constantly moving between what he "should be" and what he thinks he "is," never fully identifying with either. The Gestalt therapist asks the person to invest himself fully in his roles, one at a time. Whichever role he begins with, the patient soon shifts to another. The Gestalt therapist asks simply that he be what he is at the moment. "

Maybe this helps clarify my position. I agree that it matches pretty well with Paul's definition of mental health as well....although I would add the prerequisites of awareness and acceptance as a means to change/growth/evolution...whatever you want to call it. I just tend to stay away from these explicit terms in session with my clients, and instead focus on fostering awareness in the here and now. It also helps to deal with the issue of "normal"... I agree with Laura that while a universal standard of normal is not especially useful in any context, most individuals have some idea of what is normal for them, or are searching for it. My approach is to try and help them discover or re-discover that for themselves.

I guess a part of me also believes that as individuals, we are already "complete"...life is not so much a matter of growth as a matter of discovering what already exists...I hope that makes sense.

Where do we go from here?

After agreeing with Katy in the class discussion, I want to agree with her digitally.

As I said in class, all of the models of mental health that we have discussed - "culture as disability," "Dr. Grobstein's neuro/bio/cultural model," "Georgia Griffin's revised scientific model"- seem to promote this idea of acceptance in one way or another. In other words, we shouldn't try to "fix" mental "illness," we should strive to erase the fact that we even see anything to fix.

I don't feel like I can effectively argue against any of these right now, nor do I think I want to... In fact, I think I would say I agree with the direction that they all suggest - for not only mental health but health care in general.

That being said... If I am to to discard the cultural framework I have been working in... the idea of a healthy/ill dichotomy... even my beliefs that an organ should function in a certain way... in the interest of being less wrong, I feel like I don't have any ground to stand on anymore.

How can we come up with a practical solution from all this? While some people might be more than happy to have the healthy/ill dichotomy erased (the deaf community is an example that comes to mind), as Katy and sgibbs said, we can't deny that there are a large number of people who are not happy with their mental states and who want help.

In the bio/neuro/cultural model, it was suggested that we cannot wait around for medicine to try and figure things out. We need to address the problem that is facing us NOW. We need a solution. Do we have one? I'm left with a feeling of "what now?"

Oops!

What I meant to say was NO! The bi-polar child is not able to self-understand/evolve!

I don't know that I'd want

I don't know that I'd want to consider things thought of now as an "illness" (depression, schizophrenia, etc.) as a "different type of normal", but instead maybe as... "natural", something to be acknowledged as normal to happen? A different type of normal might suggest that someone is content being that way permanently, I don't think most people with depression feel that way. But what about also acknowledging some of the positive aspects (creativity for some, new perspectives after "recovery"), etc. "Illness" would seem to ignore those things.

The issue of those terms and Gestalt therapy is interesting. I feel them to be positive, especially evolve, evolving would never imply being complete in anyway. And never having to be complete would take the pressure off of being "normal". I do like the goal of awareness, and self-reflection, as a therapeutic process. But that only seems like the first step... what can you do with that awareness but change (perspectives, attitudes, actions, understandings, etc.)?

Defining "mental health" (or not) - PG thoughts

Yeah, I really DO think we could do better by finding a framework other than medicine ("illness," focus on "fixing things," "objective expert") to think about "mental health." And that's NOT an attack on medicine per se, but rather an acknowledgment that the issues/problems/challenges of dealing with behavior/human experience are significantly different from those medicine has so far evolved to effectively deal with. Medicine as a profession could certainly move in new directions, and probably will. But I'm not inclined to presume that we have to depend on the medical profession and wait for that. Just as I'm not inclined to presume that biology/neuroscience will in time give us the answers to difficult questions like what "mental health" actually is and when to "cross the border" with treatment, and wait for those. The problems exist now, and have to be dealt with now.

Equally importantly, my guess, as a biologist/neuroscientist, is that such questions have no "objective" answers, and that future research will bear this out. The brain is not designed to achieve "objective" understandings of "reality." It is designed to make the best sense it can of the information it has, to create "stories" that in turn alter what has to be made sense of, and to revise those stories accordingly. Again and again. There is no fixed "standard" to be reached; there is an inherent, and desirable, subjectivity in all understanding. Deciding what "mental health' is, and when to "cross the border" have always been and will always be questions that have no "objective" answer, questions that one has always had to answer and will always have to answer "subjectively," ie in awareness that there is no "god's eye" view, and that one is always acting out of, and testing, one's current understanding.

The argument here is that "relativism," individual and cultural, is actually not something to be avoided but rather something to be embraced. It, and an associated "subjectivity" is part of the very nature of human behavior/experience (see also Fellow Travelling with Richard Rorty). Diversity, among both individuals and cultures, is not a failure to achieve perfection but rather the grist from which new and less wrong things are made. And that movement doesn't depend on any fixed ideal of what is "right" or "good" or "healthy." It depends only on an ability, which all human beings share, to notice things that don't work well NOW by whatever one's standards (individual and cultural) are NOW, to try and fix them, and to learn from those actions, to revise not only our understandings but our standards (individual and cultural). To make effective use of that ability, we need as well a willingness to live with the certainty of the uncertainty, and to allow ourselves to be changed by challenging it.

So, back down to earth. What does this have to do with thinking about "mental health"? First, it suggests that we should avoid identifying some humans as "healthy" and others as "ill." Humans differ from one another along a very large number of dimensions, and those differences have complex causal relationships among them. There is always uncertainty about the value and cost of any particular difference, about which ones need to be "fixed." We all have characteristics that are appreciated by ourselves and others, and other characteristics that either we or others (or both) would at the moment prefer we not have. And we would all be better off thinking of ourselves, and others, as a mix of characteristics, some less appealing and others more so (to ourselves and others). Reducing that richness to a single dimension and identifying people as healthy or ill by some arbitrary cutoff along it seems to me not only impossible but counterproductive. Our goal should be to encourage people to enhance their distinctive and valuable differences, not to try and make them all the same.

Second, this perspective suggests that just as we all are varying mixes of characteristics, we all have varying needs for sympathy and assistance from other people. One doesn't need the concept of illness in order to accept help from other people, nor to offer it to others. Indeed, the concept of illness frequently gets in the way of both accepting help ("I should be able to take care of myself") and offering it ("Are they really sick or are they just malingering, trying to take advantage of me, etc?"). Yes, there are, will always be, uncertainties about when/where/how/who to ask for help and to offer help. But it seems to me that trying to codify this in terms of a healthy/ill dichotomy demonstrably creates more problems than it solves.

Third, this perspective suggests that both research and therapeutic practice should focus less on "fixing problems" in some permanent sense and more on opening new directions, for both individuals and humanity at large. The history of efforts to find a "cure for cancer" are instructive in this regard. Cancer is increasingly understood not to be A symptom with A cause and A therapy but rather an intersecting set of symptoms, causes, and therapies nearly as diverse as the affected individuals. Furthermore, the risk of one or another breakdown of the control of cell growth is almost certainly an inevitable consequence of being a complex multicellular organism. There are a host of therapies for cancer but no "cure." It would be astonishing if human behavior/experience were not still more complex ("Because I relish complexity, I chose psychiatry - its more complicated than neurology" ... Nancy Andreasen, NYTimes, Science Times, 16 September 2000).

This is not at all an argument for not doing more research, but it is an argument for research directed less at what sometimes seems to be the straightforward challenge of finding simple ways to restore the "ideal" or status quo, and more at opening up the range of possible ways to think about what it is to be human, ways that start from a recognition of our complexity (cf A Dissenting Voice as the Genome is Sifted to Fight Disease). And it is not an argument against using particular therapies to try and help particular people in particular cases, but it is an argument that the core of therapeutic practice should not be to "fix" people in the sense of repairing something broken but rather to help people become better able to themselves see and choose from a wider array of possible selves.

Fourth, this perspective encourages us all to see culture not only as something that influences our behavior and standards, but also something that is, and can further be, influenced by our individual behavior and standards. Yes, Culture as Disability diagnoses a problem of cultures without offering a solution. But it would be a mistake to conclude that we therefore have to live with that problem. One could instead read the paper as a challenge: how could we reconceive cultures so they don't have that problem? Yes, doing research on complex entities requires different approaches than that on simpler ones: what kinds of new approaches can we imagine? Yes, "mental health" is at the moment widely thought about in terms of "illness" and its absence. What new, less wrong ways are there to think about it?

Thanks again for everyone's contributions to my thinking more about that question. Looking forward to seeing what new thoughts the conversation yesterday evening triggered in other peoples' minds.

"Deciding what "mental

"Deciding what "mental health' is, and when to "cross the border" have always been and will always be questions that have no "objective" answer, questions that one has always had to answer and will always have to answer "subjectively," ie in awareness that there is no "god's eye" view, and that one is always acting out of, and testing, one's current understanding. "

I think that what Professor Grobstein said above (which I quoted) is true: where is the line drawn? What are the parameters of mental illness? Who decides who is sick and who is well? Those questions are complicated and hard to answer, and in our largely imperfect attempts to do so we've created decidedly faulty tools (like the DSM) and made clear mistakes along the way (like including homosexuality IN the DSM). Still, that is the goal of "getting things less wrong," isn't it? To recognize that there are mistakes, and to try and improve on them?

Because I do think there are ways in which mental illness and physical illness are akin to one another, and though they may very well not be analogous, I also think that in class we ignored the fact that a lot of physical illnesses also have many causes, some which are not always that clear. Many people with heart disease are genetically pre-disposed, some don't excersize enough, some smoke, lots have a combination of the four (and other) factors at work ... And some of those people will die of heart attacks, and some will catch it earlier and take treatment that will (likely, though certainly not necessarily work), and some may experience physical ailments ... But even more, there are still gradations in "healthy" hearts. My blood pressure is fine, but I doubt I have the perfect heart ... So, some doctor somewhere has made a relative chouce about what a healthy heart does and doesn't look like.

In mental health, the structure is not drastically different than that, and just because we don't know exactly how to treat something doesn't mean there is no treatment. (If the big issue with disease is that it can cause physical harm and/or death, then the risks of psychological disease are not dissimilar ... )

I tend to agree with you

I tend to agree with you (this is Yona, right?)

Perhaps the brain is more complex than any of our other organs (admittedly it is) but it is still one of our organs and as such can be diseased just like any of our other organs. There is a continuum of of healthy vs ill for every one of our other organs and like you said, someone somewhere had to decide where to make the cut between healthy and unhealthy.

I think the one of the main differences between mental health and physical health is only that we haven't come to consensus on where to make the cut between healthy and ill. Maybe we won't ever make that hard line (and maybe there isn't one and any distinctions we make will be arbitrary). Maybe the best way to "treat" (for lack of a better word) the people who are on the cusp (i.e. autistic people etc) is to consider them to be different as opposed to diseased.

I don't know... I don't feel like I have any answers, but throwing the medical viewpoint out the window makes me feel like "What's next?" As faulty as it is, looking at mental illness from a medical point of view is the only way that seems practical, the only way that gives me a real guideline of how to move forward.

~Laura

Another Thought

Pain: physical or mental?