Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Brain, Education, and Inquiry - Fall, 2010: Session 4

Session 4

Class is itself an experiment in a particular form of education: co-constructive inquiry

Learning by interacting, sharing observations and understandings to create, individually and collectively, new understandings and new questions that motivate new observations

Depends on co-constructive dialogue, being comfortable sharing existing understandings, both conscious and unconscious, in order to use them to construct new ones. Need diversity of understandings, need to be able to both speak and listen without fear of judgment. Need to see both self and others as always in process, always evolving.

First web paper due Monday, post and bring hard copy to class. See Course organization for details.

Starting where we are: from last weeks forum

While I enjoy the romanticism of not having a destination in mind, I still feel the logical imperative to construct a coherent narrative of the "romanticism", of the sense of "lost". I'm finding it hard to articulate all the ideas here into some kind of coherence. Maybe my brain will work it out somehow ... LinKai_Jiang

A world without rules is something we resist from our very core, both from fear and because, as inherently finite, limited beings, we want our world to be more like us so that we have a place in it ... We don't want to be floating in infinity with no ground beneath us ... Abby Em

I feel like we’re going in circles. We are saying things that without a doubt, make a whole lot of sense, but it’s all been said before ... We already identified in class that there are no objective truths but doesn’t that contradict precisely what we’re trying to in this class - find an overarching, so-to-speak, ideal/perfect system of education? ... Maybe its just my interest in postmodernism that’s making me say this, but the world is so diverse and each individual has such a different way of thinking, how will be ever be able to agree upon what society should be like? ... Amenah

If education is a means of teaching us how to perceive, or TRY to perceive, the same things as other people, to come to a consensus, is that useful? Should we be reaching for a consensus? ... kgould

Should the objective of education be to bring everyone to the desired outcome? Or should it be to allow everyone to progress their own outcomes? ... This made me think of competition. I've always thought that a little competition was a good thing. If different goals are set to provide different outcomes, do we lose competition? ... eledford

Imagine if all classes were structured in the same way as this class. At first, this made me slightly uncomfortable and nervous because I am someone who secretly likes knowing exactly what’s expected of me in a class and a specific rubric for what I have to do to get a good grade ... Turns out, there is a fairly specific structure to this class. The difference is, the structure is not oppressively exhausting. The professor acts as a facilitator ... rather than merely transferring information to us to memorize and then testing us on the material that was never actually put into practice or absorbed ... In the transfer model of teaching, the key step in the learning process is missing. How could the students be expected to use the material that they are being taught in real life if they never learn how to apply it? ... Angela Digioia

Speaking of the class loop, I like the practice. I am receiving a lot of interesting insight from across the board. Reading through the posts this week, there is clearly some deep thought going on about education, structure and pedagogy. My addition to the loop this week, in contrast, feels minimal. Minimal in the way that spending the day in your slippers reading a novel is minimal. Not like it’s a bad thing, but more just a cathartic balance when things get really serious ... FinnWing

Since we seem to have classified this course as “somewhat unstructured,” I’m questioning why I’ve been writing these responses in such a structured way, when my thoughts after class are anything but. Am I just trying to add structure? ... epeck

maybe structure isnt bad. but structured structure - the holding on and incessant need for structure is what causes claustrophobia. if structure existed and loose boundaries, maybe we'd be alright ... skindeep

imposing structure is, I think, always going to involve a tradeoff .... Because the other, totally neutral half of reality is chaos... and we have to find a way of allowing this in, rather than always assuming that we have to tame or subdue the "destructive" powers of chaos by strangling it with structure. Since if there is no empirical reality, our impulse to impose the structure that will allow us to feel like we've got it all figured out, like we really are the "masters and possesors of nature," should in fact be viewed as the destructive or hindering impulse at work here. An attempt to indulge our control-freak anxieties... when the only way to palliate them is to let that "need" for control go ... jessicarizzo

if a teacher fails to acknowledge the diversity of their students than they fail to teach [effectively] ... “Is there only one way to survive?” I think that society likes to make us think that the concept of survival or the means by which we survive is universal, but is it? I don’t think so ... L Cubed

Many students chose to write about very obvious topics and didn't see why anyone should question the topic or ask them to back it up with facts or evidence. This brought me to think about the exercise we did in class when Prof. Grobstein showed us images within images. Almost everyone at first glance, individually saw one thing and with further concentration and scrutiny brought themselves to see a different image. I wanted to draw upon this and create a similar dynamic with my group of students to help them see not only what an argument was but also the value of arguing for your perception of something ... D2B

If a person’s brain is able to make multiple associations or constructions within a given period of time when viewing a particular figure, object, does that translate to the person being more tolerant and flexible with perceiving, listening, understanding and even seeing other peoples viewpoint or perspectives on constructions of the like? ... mmc

what does it mean to "know something" about the brain? It seems reasonable to assume that we need education to discover anything about the brain, so we must first have education to know things about the brain. And the things we know about the brain are, in turn, shaped by the frameworks we have acquired through our education. So the relationship, it seems, is potentially more complex than subjective knowledge about an object ("the brain") -- a scheme which only operates in one direction ... bennett

If my brain is physically wired in a certain way, with certain chemical reactions causing me to bicker with my sister, what can I do to change that? ... Evren

the brain is often made out to be a hinderance to the creative process. The brain has come to represent logic and reason whereas the heart has come to represent emotion and creativity and generally, people are not willing to acknowledge any overlap between the two. After our discussion last class, however, it seems like this perception has some faults ... Seriously loopy science requires creativity in the sense that many perspectives lead to a greater understanding of a question and when one perspective leads nowhere, it is important to look at the problem from another perspective. This is the basis for all creativity, I think. What is creativity if not diverse perspectives? ... ln0691

What is/should be the objective of education?

Can thinking about inquiry and the brain help?

Re inquiry (from earlier session):

"Knowledge," in the sense of empirically based understanding, is summaries of past observations with expectations for future observations, a starting point rather than a final word. Knowledge is always subject to revision, either based on new observations or on new stories or both. And always has an element of uncertainty to it. Acknowledging uncertainty in existing knowledge gives everybody the the ability to play a role in creating new knowledge.

Re education: objective is not to acquire knowledge but to acquire the means to create it? to "discover how to participate in the transformation of the world"?

Adding in the brain

All knowledge/understanding is a product of the brain, a construction by it, a "story" that could be otherwise?

"The truth about stories is that's all we are ... If we change the stories we live by, quite possibly we change our lives" (Thomas King, The Truth About Stories) ... and our educational systems?

Knowledge/understanding is always tentative, not only because of cultural variation but, at a deeper level, because perception itself is never definitive

Implications for education (to date):

- Stop presenting understandings as "right," "definitive"; present instead as foundation for developing new understandings?

- Diversity in classrooms an asset rather than a problem?

- Ability to see things in multiple ways a virtue, a desired result of education?

- ????

Moving on ... Is the brain an empirical inquirer? (see How Babies Think). A story teller? How do the two relate?

The brain as empirical inquirer

|

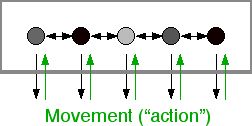

The sphaghetti (switchboard, "reflex") box model

Virtues

|

Problems of reflex model

Harvard Law of Animal Behavior

"Under carefully controlled experimental circumstances, an animal will behave as it damned well pleases"

Divergence and convergence

|

Sphaghetti (switchboard, "reflex") plus box model

Virtues

|

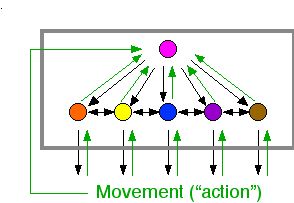

A rethinking - boxes in boxes

|

The sphaghetti (switchboard, "reflex") box model

Virtues

|

Facing up to the stereotopy, stimulus-response problem ... freeing the box from the outside world, adding autonomy

Notice loop, comparison of expectation and input, as per loopy science/inquiry

Finding all this and more in physical structure of the nervous system

Neurons and their interconnected organization

Sensory neurons, motoneurons, interneurons

Boxes and cables

Individual variation (more) and continual variation - remember neocortex

Topographic organization: the brain as a distributed system

The bipartite brain

Relevance for thinking constructedness of world but also of self: pain, phantom limb pain

Your continuing thoughts about diversity, distributed systems, bipartite brain in the forum below ....

Comments

I agree with what a lot of

I agree with what a lot of people have already said about learning how our brains work will help us. Another thought I had was how the brain has evolved over time. This came up in another class I'm taking and I wonder how people 'thought' even before people developed the ability to produce speech? Was it in images? How did the acquisition of language change our brain? Or did the brain change before we acquired language? This would also tie in to education and learning. Do we need words/language to think, have ideas, learn?

The Brain

I think that brain serves as both an empirical inquirer and a story teller that creates many constructions. In studies of child-development and the acquisition of cognitive abilities and creative problem-solving, it is clear that the brain functions both as an empirical scientist and as a constructivist story teller. Our stories undergo changes and develops (broadens to incorporate new information to encompass by the development of new constructions (schema, ways of knowing the world, methods to broader understanding). Children are much like scientists in the sense that they also are able to learn about their surroundings and environment through carrying out experiments (get their information from the environment through their senses and observations of unknowns that their brain processes, stores, puts into memory and can be retrieved at any time with the connections they make (if in LTS). Then analyzing the reactions, responses, behaviors and outcomes of the situation thereby formulating hypotheses that depict their initial observations and inally building on those inputs based on what they learn and start constructing stories. It is these schema and constructions that are constantly evolving which leads to new understandings and ideas.

When thinking about a new born, there mind is almost a blank slate. Sensory info will be organized, accumulated and saved for later use. You have to have information before you make a story. You start to make deductive reasoning from your own experience and exposure before you even know anything about the brain. Certain things are just innate that you learn as you go along and store that information for retrieval later. As you get older (as of a few years old) and you start thinking, you will be able to make associations and deduce things on your own but initially its instinctive, like feeding, survival, bodily functions, evacuating dangerous situations.

Can we train our unconscious outputs so that certain prejudices or stereotypes we have for specific situations that we learn and have made associations with (our preconceived notions whether true or false) don’t occur interfere with our understandings, interactions and contributions in different situations? It makes sense in an evolutionary perspective that unconscious output is more reactive for survival and based on instinct. Can the unconscious be made to parallel deductive reasoning? Under what circumstances would that be advantageous?

Students as scientists

Reading Simone's post reminded me of the science curriculum I encountered during an internship over spring break. The curriculum is called "modeling" and it employs inquiry based techniques where a teacher rarely gives a student an answer or an explanation, but rather asks questions that are aimed to get a student's mind working as a scientist's would. This encourages students to become explorers rather than followers in the education process, and because a teacher won't give them a straightforward answer, students often look to their peers for guidance. Thus every student becomes a learner and a teacher. The most apparent manifestation of these roles occurs during what is called "whiteboarding." For this activity, the teacher will give the entire class a problem they have to solve. The class is broken up into groups of four, and each group shares a whiteboard on which they answer the problem. In general, each group of students will be able to solve the problem, even though no single student in the group can solve the problem individually. Additionally, each member of the group is suppose to be able to explain everything that is written on the whiteboard, thus ensuring that the entire group understands the solution. Sharing knowledge and learning through inquiry seems to facilitate understanding, retention, and the ability to apply and adapt familiar problem solving methods to solve unfamiliar problems.

Teaching the Brain

We talked about the randomness/unpredictability of the nervous system last time and it made me think about whether or not the same type of system exists in the classroom. In reading through the articles about education reform, it seemed that they talked a lot about the identifying specific problems (inputs) that create unfavorable forms of education (output). Once the problem had been identified, those involved in reform attempted to look for other ways to change the input in order to gain a different output. However, oftentimes the outputs were not the desired output even though other cases had proven that such an output was possible. For example, failing public schools can sometimes be turned into charter schools. At times this change to charter schools creates a success story, but other times it is not the case. Could the problem be that like the nervous system the educational system is not based on input and output alone? If so, I would think that a different approach to reform would be necessary. There would be no room for creating formulas for success and there would have to be a much more individual approach to reform from school to school.

Teacher Town Hall

Talk about good timing! There is a discussion on msnbc right now that somewhat resembles our conversation last week in class. Some of the topics that have come up are: how to encourage creativity and team-based learning at all ages, how to train students to be critical thinkers, how to close the equality gap in schools, how to engage both sides of the brain, how to change how teachers and students are assessed, curriculum development, charter schools, etc. If you have some time this afternoon, it's on until 2 PM and I'm sure that there will be coverage online as well. There is definitely no consensus among the audience on any of the topics, which is making the conversation incredibly rich.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/39368543/ns/local_news-san_francisco_bay_area_ca/

education and the brain: beyond postmodernism?

Interesting and rich conversation last Monday evening on, among other things, the pros and cons of various kinds of structure in education and on related early findings in our "experiment in ... co-constructive inquiry." What struck me in particular was a significant amount of discomfort generated by a "somewhat unstructured" educational environment that began with a presumption that education itself was imperfect and invited discussion of the nature of its imperfections.

Concerns about negativity, about achieving nothing more than rehearsing old ideas, about the impossibility of reaching consensus about an "ideal world" (much less achieving it), of getting lost in diversity and diffuseness, and about the hazards of working without a net, "floating in infinity with no ground beneath us," are all perfectly understandable. They are, though, themselves also all worth thinking more about in the context of an inquiry into both education and the brain.

People getting together under circumstances even less structured than the present one, and having exchanges that yield novel outcomes satisfying to most or all of the people involved are, I suspect, actually the norm rather than the exception in human life in general. Kids get together (or used to?) to play "make up" games; adults "hang out" together. Such gatherings often involve a certain amount of griping and frequently yield not only a sense of satisfaction but also new ideas and avenues to explore in the future. And no one worries about whether "ideal worlds" can be created, nor about whether everything said is coherently related to everything else, nor about "floating in infinity with no ground beneath us" (though that may in fact be what is going on).

What intrigues me is that a particular set of concerns and anxieties doesn't arise in all contexts but does in some, in a classroom context in particular. What this suggests is that we tend to bring to classroom contexts some distinctive set of expectations and an associated set of concerns about ways that either we or those around us or both will fail to live up to those expectations. In the interests of trying to better understand education, it might be worth trying to make explicit both the expectations and the reasons why we fear they won't be met. And in the interests of better understanding the brain, it might be worth asking how those expectations and anxieties arise, what is involved in their construction. And how, once having arisen, they influence subsequent behavior. More generally, it might be worth exploring whether these concerns and anxieties are inevitable or might be otherwise.

For the sake of the record, my own expectations for our particular classroom context are no more (and no less) than that there will emerge for me (and others) out of sharing of perspectives new and useful ways to think about education and the brain. My own starting point is that all existing human institutions (to say nothing of understandings) are imperfect in one way or another, and that while there is no "ideal" state to be reached, one can use an identification of imperfections to get things locally "less wrong." I also tend to presume that "floating in infinity with no ground beneath us" is such a fundamental feature of the human condition that it is not worth noticing, unless/until there is a need to respond to someone's assertion that it is actually otherwise (cf Intelligent design and the story of evolution: no need for drawing lines in the sand. An update and Two cultures or one?).

Recognizing and accepting that we have nothing to work with but ourselves and each other, our past experiences, our constructions from them, and the resulting dreams for the future, seems to me not only an adequate but an appealing place to work from (cf Writing Descartes and Fellow travelling with Richard Rorty). We may not ever get it "right," but we will always have open possibility in front of us and all the needed wherewithal to contribute meaningfully to shaping what comes next. Maybe that's the point of education? to enhance peoples' confidence in and abilities to contribute to shaping the future? Maybe "postmodernism" isn't the end state but rather a useful take-off point, allowing us to make better use of human diversity for conceiving and trying to implement possible futures?

Along these lines, it seems to me important to emphasize not only the looping capability of the brain, as we discussed it in class last time, but also a creative contribution to that looping, an ability to try out things that are influenced but not determined by the past. It is because of the existence of a certain "intrinsic variability" contributing to our behavior that there can be new things under the sun. For more on this theme, see Making sense of the world: the need to entertain the inconceivable and Inverting the relationship between randomness and meaning ...

"the same conditions that leave us vulnerable to the unpredictable and uncontrollable also give us the freedom to influence our own lives and the universe in which we find ourselves. In a "meaningful" universe, either one designed by someone else, or one fully governed by impersonal laws, our role is, at best, to discover the purpose of the designer or to decipher the laws. In a "meaningless" universe, we have the room to conceive and reconceive meaning ourselves."

Appreciating the Brain

I feel a little bit torn, because on the one hand the research and findings on the brain are fascinating; and on the other hand are these findings not what inquisitive thinkers have discovered and rediscovered over the course of history? Is understanding the brain not just understanding people? Good teachers do understand how people work, but I think that neurosciences understanding of the brain can go to different levels.

This is most interesting because neuroscience, as I understand it, is either in or just out of its infancy and as a result is still finding itself. There is so much to learn about the brain, so much that is known, and then so much that is not known. By understanding the brain, educators are better able to tap into resources that can be used for individual students through knowledge of how different students or groups learn best. One potential example is that if Altzheimer's is caused by a decay in a certain part of the brain, and children who have a test done see if they are more susceptible to this disease, and the brain does have neuroplasticity ("how entire brain structures, and the brain itself, change from experience" (wikipedia)), then knowing a way (hopefully non-invasive) to improve that part of a child's brain could serve the dual purpose of improving her memory, while also diminishing the likelihood, or at least delaying the onset, of the disease. There are a number of ifs in that statement, but it also comes from some speculative research that is being done on seeing precursors to Altzheimer's (with a dab of conjecture placed on top by me).

A link to a summary of a study the Professor Grobstein posted last week that talks about Altzheimer's, and other diseases, and the brain:

http://www.dana.org/news/brainwork/detail.aspx?id=7382&p=2

Teachers and The Brain

After class, I was a little confused and honestly do not think that I retained all of the information that was presented on the brain. After speaking with a classmate, I think I have a better understanding, but am still trying to form my own views on the subject. However, this is something that I have thought about and come to my own conclusions about:

I don’t think that it is absolutely necessary for [all] teachers to know how the brain works formally because I think that sort of knowledge is best obtained through experience. This is especially true given the level of diversity found within each and every student. Having said that, I think teachers who “get it”, get it from their daily and constant interaction with their students. While they are teaching, they are simultaneously learning and forming their own understanding of the dynamics of the classroom and how their students fit into it.

knowledge and the mastery of the brain a teacher pre-requisite?

The other day in class we went over Emily Dickinson's understanding of the brain, the notion that all is held within and is a construction of the brain. In the discussion Prof. Grobstein inquired why teachers didn't attempt to thoroughly understand the brain and its workings in an effort to effectively influence the classroom and student learners. Yet is it that simple? Will the simple mastery of the brain truly drastically improve a teacher's effectiveness? Surely knowing the workings of the brain can give a teacher an upper hand but I believe there are so many other factors that play into a student's learning ability and capacity. Now if we are sticking with the Emily Dickinson theory, what does the brain make of abstract social constructions? I guess this delves into what is shared between brains. Nonetheless, what can a teacher make of shared knowing and acting amongst students and actors in their worlds that s/he (the teacher) is less than privy to?

in response to angela and epeck: if teachers...

.... perhaps don't need to be the scientists, the who, in the educational equation, needs to be? I agree that teacher's are often "made" without this knowledge, rather a basic understanding of diverse learners and thinkers.

what if, perhaps, the STUDENTS were the scientists? perhaps a greater understanding of how our minds work, how we perceive information, and the diversity of ways that we are capable of learning would inspire kids are a young age to be involved with school, and discourage feeling of inferiority in the classroom. with a greater understanding and internalization of this fact, that we are all constantly students of the world, and that by just observing and participating our brains are literally growing, taking in information and exercising, inclusion in educational settings that often are stress inducing would be more rewarding.

i remember being “left behind” in school, as other kids learned their multiplication tables earlier the i, and i was subjected to what was then highly embarrassing ridicule. (my father, in the end, had to write the answers to multiplication facts on my arm during at-home study sessions so that i would remember!) this memory made me hate math ever since... however if it had been explained to me that my brain just worked differently, not necessarily ineffectively, i may have been able to see that the skills that i learned in more "creative" subjects, where i excelled, were also applicable to maths and sciences.

Maybe the point is for US to understand how OUR brains work, and not leave it up to the teachers to totally adjust the way the classroom works, just how WE work inside the classroom.

Our Own Understanding

“Maybe the point is for US to understand how OUR brains work, and not leave it up to the teachers to totally adjust the way the classroom works, just how WE work inside the classroom.”

I couldn’t have said it more perfectly- being aware of how we learn is critical to our growth as learners in maximizing our learning.

I Agree...

Simone, I had been thinking along the same lines in terms of how much education seems focused on improving teachers, curriculum, resources, etc., but not really looking into ways to create better students more directly. That is, rather than changing everything around students but not explaining why, it would be nice to explain to students, or let the students explain to teachers, how they are learning best, and to make changes based on mutual understandings with lots of student input. I think that this would improve students, get them more involved, by adjusting the classroom to their needs.

I find the biological

I find the biological explanation of the the nervous system in the previous class to be illuminating. The fact that the nervous system is capable of moving on its own is quite fascinating. I'm interested to find out more implications of this knowledge. To what extent can we say this self-sufficient movement is knowledge-producing? I'm not sure how much the nervous signal can tell us about what it is doing exactly.

I'm curious whether there are "form-forming" parts of our brain? As noted by Gestalt psychologist and evident in our daily experience, we tend to see our sensual data in organized forms: shapes instead of linear elements and colors instead of pixels.

Teachers as scientists?

I am continually struck with the model that we’re building which relates the parts of the brain to various functions that create who we are and how we interact with the world around us. It’s truly amazing the speed with which neurons communicate to produce reactions, thoughts, words, movements, etc. As I sit typing, this very process is happening, including a something “seriously loopy” that enables me to act or assess the movement (output) that my fingers are making, as they’re making it, to produce the next word on the page.

As I continue to read articles about how to change the brain and the unique position that teachers play, I am surprised that more teachers do not have some knowledge of the biological side of the brain and the cyclical process that is constantly taking place in their students’ brains. After all, this process is directly linked to the children’s outputs and outcomes, right? I am also wondering how so many teachers, without previous training as a biologist or neuroscientist, just “get it”. I’ve been lucky enough to have many teachers like this over the years; the ones whose lesson plans and activities are able to stimulate each part of the brain to maximize the output produced (whatever that may be) and generate new inputs continuously. Here, the brain is never bored (if boredom is anything but a construct of the brain itself). How do they do that?

Great thoughts... Though

Great thoughts...

Though maybe we should discuss further what boredom is. Is it hunger of the mind? It is us being uncomfortable with having nothing to do?

I also think the idea of

I also think the idea of teachers "getting it" without formal education is interesting. Since many teachers are able to intuitively know what will interest and encourage growth in a student, how important is it for teachers to learn about the brain more than on a very basic level? In one of my classes today, the professor pointed out that although in every intro. psych text book there is a chapter on the brain, it is barely referenced throughout the rest of the text. He also said that many behavioral (and thought-related) issues can be helped without knowledge of the brain - he even went so far as to say that knowledge of the brain is often irrelevent. We all intuitively know basic things about our bodies and the world around us, and will learning about these things help or bring us further away from our very physical and innate knowledge, or help us harness tools we may have but are not using? I wonder if teachers who know more about how the brain works are better teachers in any way - my natural inclination is to guess that they're not, but I'm not sure...

In a linguistics course I took last year, the teacher pointed out that although he knew a great deal about linguistics, he was not a better orator or interpreter of speech than anyone else - in fact, sometimes his knowledge hindered his abilities...

hmmm...

I find your take on this really interesting but I must ask for more just because I myself am trying to form an adequate response to this idea. I want to be on the same page as you before I speak/write. Can you elaborate more on this? Maybe with an example. I kind of see where you are going with your statements but how do you define "get[ting] it"? Do you mean the teachers are able to tap into their students' brains and generate some sort of neurobiologically-responsible output, leading to student engagement? If so, what the parts of the brain are you suggesting as being stimulated?

I am still wondering where

I am still wondering where thoughts fit into the nervous system. I recognize that thoughts are internal and are therefore could be thought of as part of the more internal workings of the nervous system, but several ideas discussed in psychology lead me to think of ideas as an input, or at least as an output that then cycles back and is an input (like how moving your arm may be output, but seeing it and feeling it move is input). Once we are aware of a thought, isn't it input?

-Thoughts can influence the behavior of an individual - this would make it seem that thoughts are input to the nervous system, since behavior is an output, but since behavior can also be an input maybe thoughts are an output. Are there any physical or psychological inputs that couldn't also be output?

-I'm having trouble differentiating silent thoughts and spoken thoughts. According to the model we discussed in class, a silent thought would not be input, but would a thought spoken-aloud be input? If there is no audience for the spoken-aloud thought, what differentiates it from a silent thought? This issue reminds me of split-brain patients, who sometimes must vocalize what they see in order to internalize it (for example if an object is in a field of view where only one eye can see it, and the "thought" of the object being there must be vocalized in order for the other half (that doesn't see the object) to understand that the object is there) - just because they have to vocalize their thought doesn't make it any less of a thought, but an observation that is spoken and influences thought definitely seems like input.

-Basically, I'm unclear on how to distinguish input and output. The more I think about it, the less I am able to distinguish the two...

- Here's the article I mentioned in class about neurological differences that lead to seeing things in multiple ways..it's a short and easy read (I think this link might actually only be a summary of the original article) - http://gizmodo.com/5629780/why-your-brain-flips-over-visual-illusions

ick. leeches.

So I know my feelings don't particularly matter, but I was having this complicated emotional reaction while being regaled with the tale of the undead leech last night in class. I guess one way of assimilating this new information could make us feel more powerful. If our brain is acting on the world as much as reacting to the world, we have less reason to feel like cogs in a deterministic machine. But I'm afraid the language being used to talk about the nervous system as something "active" was somehow personifying it, projecting this nice, human sense of agency that doesn't really seem to be telling the whole story.

As has been noted, all of us gathered here presumably care about education, think it's worth thinking about, theorizing, improving. So I wonder if anyone else was simultaneously a little awed and a lot repulsed by this pretty gruesome, science-fiction image of the brain in the jar... outputting, all by itself. I wouldn't ordinarily think of that activity as "acting" on the world. Little sparks are being emitted. And the brain runs some "tests" to see if those sparks have the anticipated effects... but that's less like active inquiry than an ongoing, equilibrium-seeking impulse to reorient oneself in an environment that's always going to have some fluidity to it. Which means always taking baby steps, and always playing catch-up. No room for boldness or vision there (meaningless mission-statement words, we should learn to do away with?). Because the brain isn't really asking questions... or if it is, it's not choosing what questions it wants to ask, or articulating those questions itself. Maybe I'm the one personifying where I shouldn't be now, but it does seem like understanding personness wants to be somewhere near the heart of this course.

Tonight’s class seems to be a

Tonight’s class seems to be a potential turning point in the semester. As a class, we aired frustrations, were introduced to a model of the brain (i.e. the nervous system), and we seemed to not get stuck on points as much as in previous classes. That is all very positive and exciting.

In the spirit of posting early and often, here a couple thoughts that I feel are post-worthy:

Firstly, learning about a model of how the brain works is great. An important part of education is engaging other people’s ideas and hypotheses, trying to learn and evaluate those ideas, and then try to continue to build and incorporate into other situations. This brain model is certainly exciting to engage and learn about.

Secondly, I am very interested in the idea of what happens when we are not explicitly learning, studying, and engaging the copious stimuli in our lives. There is an article that Professor Grobstein posted a link for in the session three forum, which I look forward to reading, and I can share my thoughts once I have read it.

For the moment, how important is it to try to turn off/disengage from our logical, rational mind and just do things that do not require active thoughts? I think it is very important, and I am curious if anyone feels like sharing his or her own thoughts on this. For me, I think it may be most important for the rest and rejuvenation it provides. Anecdotally, I have found that if I do not take this time and space then I eventually just crash.

Anyway, good session tonight!

your brain on computers

Saw this in the Times a little while ago:

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/25/technology/25brain.html?_r=1

It's part of a series exploring the ways in which our inability to put down the iphone(or whatever) and the constant influx of "input" such devices bombard us with, for more than five seconds may or may not be making us dumber and less creative as a society. I think you can navigate from here back to older articles in the series that talk more about the good things "downtime" does for the brain too.

I saw this article as well

I saw this article as well and I thought it was very interesting. It's definitely possible that reading about these effects is making me feel them, but I can really relate to the feeling that some fundamental changes to my mental life have occurred since I started using computers and phones and whatnot on a regular basis. I remember that as a child I was a great and insatiable reader, always seeking out new books and new information; ever since I began getting things fed to me through technology, reading has seemed more difficult and less compelling. Have to lead my eyes physically through an article -- and I know this sounds crazy -- is simply not the same thing as reading on a computer, or using the internet more generally.

But i also wonder whether the alarmist aspect of the article is realistic. For as long as there's been anything even remotely like the "technology" that we have today, there have been Luddites and doomsayers. But, like we're learning in this class, the brain is incredibly plastic: I don't think it's realistic to assume that just because we're seeing new patterns of brain activity, that those are "bad" or deviate from some original norm. I'm not sure that there realistically is a norm to make reference to: hasn't the brain been evolving continuously, just as we have? Won't it continue to do so?

Brains, computers, and different ways of thinking/being

I too think an alarmist approach to the brain and computer impact isn't warranted: the brain will indeed be affected by computer use, as it has been by other cultural changes in the past, but its well-nigh impossible to say what those effects will be in the long run, much less to try and evaluate them. At the same time, I think it is indeed worth thinking more about the significance and the meaning of "downtime," of doing things "that do not require active thought." Our inclination to spend time that way tends, irrespective of computers, to be much less than is encouraged in many more meditative cultures, both eastern and western. For more this theme in a particular clinical context, see Thinking more about depression as "adaptive."

Interestingly, doing things "that do not require active thought" may not be quite the same thing as disconnecting from the outside world. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi's Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience argues for the desirability of a state of absorption, engagement with whatever one is doing, a state in which normal concerns/worries disappear in part because of the completeness one one's engagement with things outside oneself. And computers may in some contexts/situations actually contribute to that. See Life/education as a game.

Post new comment