Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Brain: Basics re "Mental Health"

|

Mental Health and the Brain:

|

|

Our second session and resulting on-line forum discussion seemed not to entirely settle the question of what is meant by "mental health," suggesting instead that part of the explanation for the existing fragmentation of the mental health care system may have to do with different and in some cases conflicting conceptions of what "mental health" actually is. For the next several sessions, we'll be looking at the brain and features of it that may suggest more coherent ways to think about "mental health."

Readings for this week

Where we've been so far

"All this disagreement about the idea of soul, self, mind and body as being seperate entities makes the study of mental health a fractured and incongruous practice. To which part do we owe the most loyalty and which part needs to be cured?" ... akerle

"I think we are actually, truly downplaying mental illness if we decide that mental health is basically subjective. " ... ysilverman

"My definition of mental health consists of two criteria: personal and societal. Yet I am unsure how to treat the tension between them." ... jrlewis

"While we are replacing the terms/ideas of "illness"/"health" with new ones, the idea too of "help" should be more broadly defined/termed, as an exchange/engagement with other individuals (whether "experts/professionals" or not)/culture." ... LauraC

soul, self, body, mind, individual, culture, subjective, objective, normal, abnormal, physical, mental, biological, psychological, assistance, exchange, health, diseased (ill) ....

What we're looking for is a way to think about "mental health" that acknowedges its complexity, rather than requiring us to choose between things presented as alternatives. And that makes sense of that complexity in a way that is practically useful?

"If a person presents with a symptom that is mentally unhealthy (by whatever standard of mental health we conclusively decide upon) the person who is helping them must then look to what could have caused this to be the case. Maybe it's social, maybe it's biological, maybe it's existential, etc. Then, a treatment plan is decided upon, to restore this person to mental healthiness (to being able to understand their current condition and how to change it, or whatever other definition we would like). This treatment plan might involve talk therapy, it might involve drugs, it might involve meditation. Most importantly, it must involve the patient's continuing involvement in self-assessing and assisting their helper is assessing them." ... kmanning

"We need to think deeply about a good definition of health and illness that deals with both on a holisitic level, without stigmatizing, but still opening up our ability to really help each other. " ... adiflesher

"So it almost returns us to the notion that "mental illness" had much more to do with disconnect from the (social) norms than anything else- yet for those of us who have felt the rush into the pit of darkness and apathy, there seems to be more than just social norms. So what does a truly biopsychosocial definition, or an otherwise multifactorial one begin to look like?" ... Judie McCoyd

"I cannot stress enough how important it is to me for personal responsibility to play a part in the definition. Even people who are struggling need to be held accountable for their “stuff.” ... merry2e

A way of thinking that acknowledges an important role for the personal, what is going on inside ourselves, without neglecting the physical, the interpersonal, or the cultural? Want "help" with what seems out of control without given up personal agency in its entirety (maybe even enhancing it?)

Alternate models of mental health

- Child-rearing

- Education

- Science

- Biological evolution

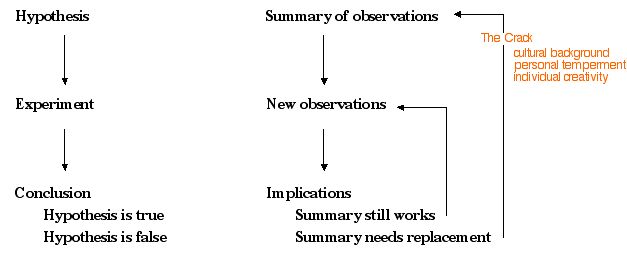

Science as truth in lending and as a model

Traditional Loopy, story telling and revising

- Empirical science is not and cannot be an account of "reality"

- Empirical science provides a way to account for observations but leaves open the possibility of others

- Empirical science has inherent and desireable subjective elements

- Empirical science is a story, a way to account for observations whose significance is as much in the new questions it raises as in its use in the present

- Scientific stories should always be taken with a grain of salt

- One never gets it "right," but one can always get it less wrong

- The standard is local, not global, fixed, or eternal; there is no single right way to get it less wrong

- Wherever one is at any given time, one has the resources to get it less wrong

- What is important is not what one can't do but what one can do

- Getting it less wrong can be facilitated by borrowing from/contributing to others getting it less wrong in their own ways

- "Meaning" derives from the process rather than existing in the abstract, and is itself revisable

- "Mental health" = a measure of a continuously variable and multi-dimensional capacity to grow/change/evolve/create and recreate meaning for oneself and others?

The Brain (= nervous system): Starting Point for a Story

|

The Brain - is wider than the Sky - Emily Dickinson (1830-1886) |

|

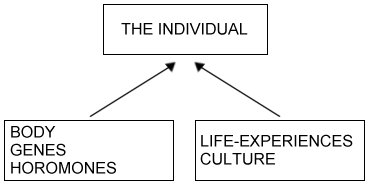

Suggests brain as central node, a locus for complexity

|

|

- not genes versus environment but genes AND environment

- not physical and mental but physical AND mental

- not biology versus culture but biology AND culture

- not individuals versus society but individuals AND society

- all influences on mental health, including the self, are influences on the brain

- brain is different in each individual, constantly changing?

Suggests all human experiences/thoughts/understandings are constructions of the brain

- meaning doesn't exist in things but rather in our interactions with, characterizations of them

- who are we in terms of the brain? how does the brain create meaning? (see Illusions, ambiguous figures, and impossible figures: informed guessing and beyond)

- how does the brain create self? other? culture?

Is the brain THAT big? Starting to think about it .... and getting less wrong

|

|

| The problem | Another loop |

- not a stimulus/response machine but an interconnected set of sem-autonomous input/output boxes at several levels of scale with small scale architecture continually being changed by its own activity

- excitation (including self-excitation) and inhibition

- lots of room for individuality and change

- sensory neurons, motor neurons, interneurons

- signals are action potentials, themselves context dependent for meaning

- action/perception as patterns of action potentials in neurons, so too feelings/thoughts/understandings

- who's in control? where is self?

- I-function (experiencer, story teller, conscious) as distinct box

- Pain (like all other "meaning") is in the head

- Self is distributed/variable

Your thoughts in the on-line forum ....

- Brain as node?

- Can find what we need in there?

- Does it help?

Comments

Interesting little tid bit

I thought this was interesting regarding the whole mind/body dynamic:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p9Glq9SVSxQ

This video is related to

This video is related to Antonia's video. I watched this for my psychology class last semester. The patient had the corpus callosum removed because of severe epilepsy. I find very clarifying Dr. Gazzaniga's definition of mind.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jvjITzq4O6c

As a psychology major in

As a psychology major in undergrad, I often felt that there was a gap between the "harder" natural sciences (chem, bio, physics) and "softer" sciences such as psychology, anthropolgy etc.. Maybe it was only at my school, but I really felt like psychologists had an inferiority complex about it. Or maybe it was just me...

Anyway, I wonder why there needs to be a rift.

Dr. Grobstein got me thinking about this in his first post where he alluded to entropy. Here are some quotes from Dr. G's post:

"We have randomness (meaninglessness) as a driving force that causes new things to be created."

"Perhaps those things, rather than being failings, are actually what drives the ongoing process of 'getting it less wrong'"

and here are some quotes from the Wikipedia article on entropy:

"[Entropy] is a measure of the randomness of molecules in a system... Spontaneous changes, in isolated systems, occur with an increase in entropy. Spontaneous changes tend to smooth out differences in temperature, pressure, density, and chemical potential that may exist in a system"

I see a lot of parallels.

I guess my point is... It's not hard to imagine that mental and psychological phenomena may obey some of the laws of nature that "hard science" has

discoveredgotten less wrong. Perhaps we would be well-served to use these principles as guides and/or foundations for new exploration into mental and psychological phenomena.Another example... I like the argument that Marty makes for a metaphysical aspect of reality. He says that nothing comes from nothing... something is, something always was.

That sounds like the first law of thermodynamics to me.

mixing hard and soft and getting ... mental health?

Pleased to be a tranmission vector for the idea (meme?) that the hard sciences have things to learn from the soft and vice versa. Maybe we could extend the idea to better interconnect science with the social sciences generally and humanities as well? Another example of not picking between two sides but using their differences to find new ways to think?

Clever use of strikeout. How'd you do that?

strikeout

the web and mental health

It's funny ...

Because as much as I took (and in some ways still take) issue with our attempt to do away with the idea of "mental illness", I am totally on board with both the reorganization of our ideas on the scientific method (though I agree with jrieders above that perhaps this is just semantics, that it is generally accepted that whatever we say today, and whatever we "prove," may of course be false, that we are always trying to understand things less incorrectly) and with the idea of the brain/mind as both a parser and creator of reality.

In today's (tomorrow's?) New York Times the Modern Love column is about how someone with a frontal lobe injury tries to reconcile his current reality with his past reality, not fully able to understand the world in the ways he used to, or others do ... And I think we all do this to varying degrees. Perhaps it is partially because I write fiction, but I think so much of our reality is based entirely on how we percieve it. Additionally, I always find memory studies fascinating -- how likely it is that we will misremember events, make up events, how easily we can be influenced to remember things differently. One of the studies I have always found particularly interesting is the one in which people created memories of interactions with Bugs Bunny at Disney World -- despite the fact that Bugs is not a Disney character.

I also think our perceptions of reality are very much culturally -- or subjectively -- based. A friend often tells the story of taking some sort of iq test when she was younger, and being shown a picture of a three-legged table.

"What is wrong with this picture?" she was asked, and later it was brought to her mother's attention that she hadn't mentioned the missing leg.

"Of course she didn't," her mother had responded ... In their house, they had a lot of modern furniture, including a three-legged coffee table.

Perhaps slightly differing from Paul, but in the same vein, I think that regardless of whether or not shared perception is an example of objective reality, or simply a brain construct, there is something important about life as a social being as sharing with others a perception that reality is shared. There will always be variations in the things we are sure! happened, and yet both comfort and reassurance are derived from a sense of a shared reality.

I also read the Powers book last year, and in a lot of ways Capgras reminded me of my own grandmother's changing perception of reality with early alzheimers (not uncommon) ... A year or so before she was diagnosed, she became very agitated because she and my grandfather were living in a home that was an exact replica of their real home in every way, but that was not their home. Every aspect of it was the same, but she was positive it was the wrong home. My father would try to question her, first just to get her to see she was wrong, and then just to ask why, if everything about her "new" home was exactly the same, she cared if they had moved. Couldn't she live the same life in this replica of her home? But of course her agitation continued. Maybe she was right, in a sense, just as in "The Echo Maker", what does it mean to be the same person everyday? Aren't we each just our own constant reinterpretation of events? Maybe our houses *are* different everyday ... But if our brain isn't comforting itself with this thought, what use is it?

I think that in creating narratives, our minds often strive to jive with others -- to make connections in shared perceptions or communal cues. Often people who have traumatic brain injuries do explain the world differently (and perhaps in ways no less correct), but they also often feel frustrated, maybe vaguely aware that their perception is a bit off kilter, maybe just less able to make their narrative comforting. I am more than happy to decide that being mentally healthy means feeling able to construct a personal narrative that is bolstering and personally sensical. In a way, the goal of our brain is not necessarily to get reality "less wrong", but to make our lives easier. (Case in point -- often people with personality disorders/PTSD view the world more in terms of luck and less in terms of personal agency. In reality, many of these people may have experienced "unlucky" events over which they had little control. Is their perception less right? Perhaps not. But is it helpful to them? Well, perhaps not, too.)

lessons from/about mental health/life

Delighted to both "take issue" and seek "connections in shared perceptions," indeed to do the former in pursuit of the latter?

Along these lines, I too think "illness" has been (and may still be) a needed improvement in thinking about mental health; its certainly an improvement over some earlier ways of thinking about it. But it too has some problems, particularly in the realms of agency and encouraging agency and diversity and encouraging diversity. My guess is we're not actually so far apart on this at this point.

Nor, for that matter, are we, I suspect, so far apart on the "reality" issue either. There are indeed different worlds, and your three legged table story is a nice example. And we do indeed seek "shared reality," partly for the "comfort and reassurance" interpersonal connectedness provides. But the story of your grandmother, and the Echo Maker suggest there is something else involved as well. People may actually decline interpersonal "shared reality" and the associated "comfort and reassurance" when it doesn't resolve an intrapersonal conflict.

What we seem to seek is not just interpersonal agreement but intrapersonal agreement as well. And the two may push us in different directions. Is one or the other "healthier"? Or are they both perhaps not actually ways to achieve "comfort and reassurance" but rather motivators for our continuing exploration of new ways of being? Maybe the brain isn't designed "to make our lives easier," but rather to faciliate our lives as explorers?

An interesting idea about

An interesting idea about the personal importance of constructing a consistent story. I spent a significant amount of time with a patient suffering from advanced Alzheimer's. Yes, I mean to use the word suffering. The mental states he experienced caused him anguish and anxiety. What I found interesting, was his attempt to mask his confusion. He was a master at evading giving answers to simple questions. He made use of such tactics as deflection and humor. The level of sophistication of his strategies was impressive. Yet, I wonder how much comfort they afforded him. A lone storyteller?

It often seemed like he was too scared of criticism to share his own meaning or stories. Throughout the course of his illness, he had learned to anticipate conflict between his story and the accepted, communal story or stories. To a limited extent, he was conscious of his inability to defend, factually, his story. Therefore, he chose not to share his personal story.

It was not always so, earlier in the development of his disease, he much more comfortable sharing. Perhaps this was because he perceived that his story was not significantly different from the “accepted story”. As he encountered increasing opposition to his story, he began editing out the controversial elements. There was never an attempt to resolve the conflict between the two stories. In fact, his story was discriminated against on the basis of his material (physical) illness. So he stopped participating in the storytelling activity.

A storyteller without an audience is a sign of mental illness? Or more generally, the lack of storytelling activity is mental illness.

Reality, Truth, & materialism

materialism, story, and the brain

Hmmm. LauraC and I have been back on forth on this one for a while, without my quite understanding what's on her mind. This morning I think I get it, and think it relates to Paul's concern as well. Let me take a crack at both ...

Descartes' dualism (or at least what was subsequently made of Descartes' writing) invoked two distinct realms, one of matter and the other of spirit. And, in this context, the story that all human experiences are "constructed" might be (sometimes is?) heard as asserting that everything is "spirit," ie that there is no "matter." I suspect in fact that in my effort to emphasize the importance of "construction," I may contribute to that way of hearing the story. Mea culpa.

The story should perhaps emphasize more that all human experience is a construction by the brain, which is itself organized matter, and hence experiences (and stories) too are organizations of matter. The story of the constructedness of human experience should not be heard as asserting that story (or spirit?) is all there is, nor that story (or spirit) exist in a realm parallel to that of matter, but rather that story (and spirit?) are forms of organized matter (just as culture is forms of organized individuals).

What follows from this is that properties of matter are not irrevant to thinking about human experiences/construction/stories (and spirits?). While they don't determine any of these things, they do influence them. Yes, I am likely to get into trouble if my story doesn't include the likelihood of failing on my fanny if I try and sit down without a chair there. And my story is particularly problematic if everyone other than me has a story that acknowledges that. Equally importantly, since my story is itself organized matter it can readily play a causal role in reorganizing matter. If there is no chair here, I can reorganize matter to allow me to sit down (by going and getting a chair, or even making one).

That all of human experience is a construction of the brain is not a classic "idealist" position (Berkeley: there is no matter but only ideas). Nor is it a classic materialist position (everything follows necessarily from the properties of matter). Nor is it a classic dualist position in which matter and spirit/ideas each have their own independent existence. It is instead a story in which there is both matter and ideas/spirit, because the latter are forms of the former. One can have BOTH matter and ideas (and bidirectional causal relationships between the two), just as science can be BOTH objective and subjective because objectivity is created out of subjectivity.

Is there something "out there"? "outside of us/our brain"? There certainly seems to be, and there seems to be something in here that makes up us/our brains as well. We can and do productively tell, compare, and revise stories about that (those?) somethings. What we can't do is to compare those stories to what is "really" out there/in here. That's too bad if a completed description of "reality" is one's goal. But maybe "reality" is actually less interesting than what one can make of it? In that case, one can actually take pleasure in the inability to provide a definitive description of it, and in the play of alternative realities that leaves open for humans to create.

Continuing on that thought....

Last semester, we also came to the same conclusion (or hypothesis) that our reality - or perception of it- is just a construct of the brain.

I insisted that there are some concrete realities that transcend one's perception. For example, if all the brains in the entire class agreed that we were sitting on chairs, then the concrete reality was that we were sitting in chairs. I thought that if many independent minds share certain perception of reality, then the perceived reality must be real. Any thoughts?

Nowadays, I'm not so sure because the fact that the perception is shared may just be a construct of the brain in itself...

Radical Therapy: A Political Activity?

I'm hoping to join you for class next Monday night, and in anticipation...

have been mulling over my own current project: bringing 5 years of intensive therapy to a conclusion, looking @ what didn't work (esp. my dissatisfaction w/ the lack of "reciprocity"), and trying to find a satisfactory way to "end"...

to bolster myself along the way, I have been looking @ a very 60s text, The Radical Therapist, which insists that therapy--which has been dominated by gradualist models that bolster the status quo--needs to remake itself as a political activity. The assumptions here are that the essence of all psychiatric conditions is alienation, and that alienation is the result of oppression, about which the oppressed has been mystified or deceived.

Oppression + Awareness = Anger

Liberation = Awareness + Contact

I guess what I'm trying to do is put on the table some questions about the political dimensions of mental health practices in this country: the degree to which they preserve the current state of things, and the degree to which they might try to interrupt them...perhaps these questions offer other angles into talking about "the material"/"real" world?

Like Sophie, I am interested

What struck me when Prof Grobstein kept asking us if facts about the world were to true (and we were supposed to continuously respond no) was that I kept wanting to say "they are true to whomever thinks them". Sure, consciously I can doubt that there is actually a computer in front of me right now, or that I am actually a body, but my unconscious self that is telling me to act even before I am conscious of it DOES BELIEVE THOSE THINGS TO BE TRUE, it must! Why else would it be acting at all? In fact, to my unconscious mind, THOSE THINGS ARE TRUE. If we are going to give anything a capital T Truth value, I would say it is the inputs our unconscious mind is acting on. We can question all we want consciously, but until we can make our conscious thoughts affect our unconscious beliefs (“beliefs” being yet undefined – maybe they are neural pathways, maybe they are something less concrete in the “mind”) we are not actually affecting change in ourselves. When I taught myself in seminar on Monday to make the flashing dots on the warning sign move in all directions, I truly felt like “reality” had totally slipped out from under me, and felt as though if I tried hard enough I might be able to control absolutely everything around me. However, until I meet Morpheus and learn to make a spoon bend in front of me with my mind, reality does exist for ME. Reality is the facts about the world I cannot or have not yet convinced my unconscious mind to believe are false. Or could be false, if I wanted them to be. Training myself to see the flashing lights move in different ways made me absolutely convinced the conscious “mind” can and must affect the unconscious “brain”.

What science is then is more than just finding commonalities between our conscious interpretations of the world, but also finding commonalities between our unconscious notions of reality. I guess I am a believer that it doesn’t matter if there’s anything “really out there”, because to our unconscious minds, there always will be.

mental health: towards a bipartite brain

I'm not inclined to go quite so far as to say "it doesn't matter if there's anything 'really out there'," but you've put your finger on a really important distinction, and some of its implications. Yes, what we've been talked about "are all questions of the conscious mind." And there is indeed more to the brain than that, much more. As we'll talk about this coming Monday.

"Reality is the facts about the world that I cannot have not yet convinced ny unconscious mind to believe is false" is a nice way to put it, maybe slightly revised as "Reality is what one part of the brain has yet to persuade another part of the brain could be different." Maybe we could rephrase "to my uncconsious mind, those things are true," as "it doesn't occur to my unconscious mind that they might be otherwise"?

Regardless, science (and culture) is certainly "more than just finding comonalities between our conscious interpretations of the world ." Finding commonalities" between our unconsciousnesses is at least as significant. And "until we make our conscious thoughts" affect our unconscious "we are not actually effecting change in ourselves." At least not stable change.

Stuff

Is there a role in this conversation for the nature of conscious and unconscious thought? In what ways is our behavior informed by factors of which the I-function is not aware? What about free will?

Ryan g in his post discussed the nature of “assigning meaning” to things. Is this not something we do anyway, whether consciously or not? Is there some part of our brain that naturally catalogues our experiences and compares them to that which we are currently “perceiving” in an effort to create a match, to create order out of disorder? As there are limits to the amount of information, at any given time, our brains can process, visual, auditory, etc. there must be some processes by which the brain filters the vast amount of information and through the various inputs and outputs and looping creates a mosaic that is “reality” for a given individual.

"…freedom has a twofold meaning for modern man: that he has been freed from traditional authorities and has become an 'individual,' but that at the same time he has become isolated, powerless and an instrument of purposes outside of himself, alienated from himself and others; furthermore, that this state undermines his self, weakens and frightens him, and makes him ready for submission to new kinds of bondage. Positive freedom on the other hand is identical with the full realization of the individual's potentialities, together with his ability to live actively and spontaneously."

The above is taken from Erich Fromm’s book, The Fear of Freedom (page 233, Published by Routledge, 1960) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erich_Fromm

I like the idea of the “full realization of the individual’s potentialities…”

"Who does depression hurt? Everyone."

"If the mind is, indeed, within the brain, which is within the body, is there a point at which the inextricable link between them can be seen as integral in “illness” and not just mental “illness.”"

I like this idea and I think it's very important for people to realize that mental illnesses manifest themselves very physically. Take anxiety -- someone will have racing thoughts maybe about others' negative reactions towards them and might think things like, "I'm going to die. It will be so embarrassing." And all the while their heart is racing, they are sweating, they feel nauseous, they can't stop shaking, they can't breathe, and so on. How can you call that strictly mental?

I also thought about that commercial for an antidepressant which says, "Where does depression hurt?...Everywhere." How many times has someone complained of "unexplained" physical pains only to receive the response, "It's all in your head"? People need to stop thinking that some illnesses are just "all in your head" and therefore aren't legitimate.

illness and freedom, all in the mind (and culture?)

If its all a construction of the brain, then indeed "all illness is in some ways mental illness." And we should stop distinguishing between "real" problems and those that are instead "all in the head"? Find a "less wrong" way to distinguish, for example, between a pain originating from an injury to the leg and a comparable pain experienced in someone not having a leg? Recognize that the state of the brain may well have impacts not only on the experience of the injured leg but on the injured leg itself? Yes, there may well be implications here not only for thinking about "mental" health but health in general. And yes, there is "a role in this conversation for the nature of conscious and unconscious thought." We'll get there this coming Monday.

Nice to have Fromm on the table too. Outside Britain (which I was when I ran onto it), the book was published as Escape from Freedom. Fromm certainly encouraged people to "live actively and spontaneously" but he also suggested that such freedom coud, depending on the state of society, become "an unbearable burden ... identical with doubt, with a kind of life which lacks meaning and direction." Sounds like "full realization of the individual's potentials," like other ways to characterize "mental health," is dependent on cultural context.

God in Dickinson's Brain

I was interested by the last stanza of Dickinson's poem on the brain that Prof. Grobstein references above:

As syllable from sound.

Does she suggest that God is a creation of the brain--as the sky and you and me are in the first stanza--or that the brain is more like God itself, and more the creator and source of all reality, rather than the one being created by the other?

I'm interested in continuing this connection between God and the brain, and in connecting to the earlier comments on how religion enters our conversation about mental health. Is religion a "disability" for the study of the brain? Or, perhaps, as we consider an individual or culture's particular vision of itself in relation to God, it will inform a definition of "mental health" as it relates to a particular story. Dickinson couldn't separate God from the brain in her poem--and it seems to me that many people/patients will also have a hard time separating god/the creator from the brain, that which creates meaning.

brain = God

I really like this God = brain idea...

As we learn more and more about the nature of things, (or get things less and less wrong...) it's interesting to reinterpret ancient religious texts in the light of new discoveries.

How about this one:

20Once, having been asked by the Pharisees when the kingdom of God would come, Jesus replied, "The kingdom of God does not come with your careful observation, 21nor will people say, 'Here it is,' or 'There it is,' because the kingdom of God is within you."

Luke 17:20-21

"the brain is just the weight of God"

Many thanks. I've been using/thinking about that Dickinson poem for a long time, without having a way to make sense for myself of the third stanza. And you've given me one. Yes, its NOT parallel to the first stanza. One DOESN'T fit inside the other. Instead they are the same: brain/God as "the creator and source of all reality." It would be interesting to look at the critical literature on Dickinson to see to what extent that reading has/has not been proposed/generally recognized.

Delighted, of course, to have further conversation about the relation between religion and mental health. Religions and spiritual traditions, of course, are themselves pretty diverse, some having a God, others gods, and stil others making do without any concept of a supernatual, a divine, or an eternal. I suspect that diversity too is relevant for thinking about mental health.

Grobstein's question marks,

Grobstein's question marks, surrounding his body-box, indicate that we don't have much certainty about what exists outside of our own minds; even our own physical bodies are a source of mystery. I can't accept that I have a body with such and such dimensions and then go on to doubt the environment that my body lives in, therefor I think it is fair to say we don't have much certainty about our bodies. Likewise if my brain/mind are sitting inside of my head (with such and such dimensions and relation to the rest of my body). But, I don't have any certainty about my body so I think it is fair to say we don't have any certainty about the physical properties/workings of our brains. What we are left with is a very immaterial self (NOT unimportant... think about the irony associated with our common use of the word immaterial=insignificant...) about which we can be certain. This self is Descartes cogito that he decided to stick into the brain into what he called the pineal gland. We are doing the exact same thing if we reduce ourselves to a brain inside of a body.

Ryan's point about the firing of neurons causing ideas or ideas causing the firing of neurons is excellent. We don't/ probably can't know the answer to that question.

JrLewis makes a great point as well about the different ways of addressing the questions we are discussing. Depending on which way you view the world-- take your pick from the list provided or from some other-- you will approach these questions in a particular way and be looking for a particular kind of answer.

In response to the religion comment above:

I don't think every religion necessarily attributes a metaphysical aspect to human beings, although most do.

But, what is significant about religion is that it acknowledges a metaphysical aspect to reality (the question marks surrounding Paul's body/brain box) I find it hard to deny this aspect of those question marks. Think about it, nothing comes from nothing: something is ==> something always was. Physical things can change and do not exist necessarily ==> there must be something that is which is not contingent but necessary. And, it cannot be anything like what we experience since we only experience contingent/changing things.

So, if we are going to talk about what mental health is from a perspective that accepts that we are a brain in a body and that everything we experience is subjective (in and of itself.. nobody argues that our experience of a thing is objective) we will get certain kinds of answers which might be useful and productive.

If we talk about mental health from a perspective which suggests that there must be more to a human than the body and brain and that there is an objective real world out there in which our bodies reside we will get another group of answers which might also be useful and productive.

Which story makes most sense to you?

mental health: sense, certainty, uncertainty, and usefulness

Yes, indeed, there are different perspectives from which come different things "which might be useful and productive." But, given that, maybe the question to ask isn't what story "makes most sense to you" (a skull or a woman looking in a mirror?) but rather "what story seems to offer ways to think about things that might be more useful and productive than what has yet been thought?" All other things being equal, one might in that case choose to further explore a story that, at the moment, makes less sense to one. After all, one already has significant experience with the usefulnesses as well as the problems of stories that make more sense.

Along these lines, I'd be inclined to argue that "there must be something that is which is not contingent but necessary" qualifies as a story with which most people already have substantial experience. A story that everything is contingent might, for many people at the moment, make less sense but prove in the longer run to be more useful and productive. If "we only experience contingent/changing things" perhaps a story that works with that that would be more useful than one that doesn't?

Descartes is interesting in this connection. Yes, we don't have certainty about either the outside world OR our bodies. And we don't have certainty about "the physical properties/workings of our brains." So, if we put inside the brain a self about which we are certain we would indeed be simply be replaying Descartes in a modern guise. But maybe we could put there a self about which we have some uncertainty, just as we do about the body and the outside world? Descartes was a wonderful skeptic, but perhaps was unabe or unwilling to carry his arguments to their limit? See Writing Descartes. Perhaps there is no certainty anywhere, including inside ourselves, but only varying degrees of uncertainty? Which are, in turn, the cracks through which we escape determinism of all kinds, and acquire the capability to bring genuinely new productive/useful things into existence?

the ghost in the machine?

All this discussion about the brain reminds me of a brilliant New Scientist that came out a year or so ago. It was the 50th anniversary edition of the magazine and inside were prominant scientists who tried to answer some of life's more complex questions (i.e is there free will? Is the universe deterministic etc.) Inside there was an article about the brain (that I would have posted but it costs money and I am, sadly, an impoverished student) talking about the 'ghost within the machine'. Or the lack thereof. If we want to discuss the idea of culture as disability as regards to mental health then, at this point, I think there is no greater cultural disability for the study of the brain than religion.

The 'less wrong story' that we have come up with at this point states that all human functions and experiences are a product of the brain. The brain and the mind are the Same Thing. Religion inherently separates the mind from the body/ brain and skews universal perceptions of self. The 'ghost in the machine' serves no purpose other than to jam the gears. Many religions dislike the notion that we can 'trivialise' the human experience down to the firing of a few synapses. What if we acknowledge that the human experience is a creation of the brain but that doesn't make it less wonderful. In fact, I would argue that we don't need a ghost because the machine alone is deeply subtle and complex.

Mental health, religion and the "ghost in the machine"

Lots of interest in the religion matter. See MartinBayer, mstokes, and comments on their comments. Is it enough that the "machine alone is deeply subtle and complex" or is there something more at issue? Some other function that a "ghost" serves?

Maybe we should call it A "less wrong story" instead of THE "less wrong story"?

Thoughts on Monday...

A few initial thoughts on the Monday discussion:

"Nothing has meaning besides the meaning the brain gives it."

I believe this statement...

but I don't really know why. I'm trying to figure it out. I think that illusions are good evidence for this story. For some seriously cool illusions check out Sidewalk Chalk Guy.

Maybe it's just easier. Instead of debating infinite possibilities, why not just come to the conclusion that all possibilities are erroneous. Seems kind of dreary... like quitting.

Perhaps my problem with assigning inherent meaning to events/behaviors/conditions is that it implies that someone decided upon the meaning. Who decides on the meaning of things? God?

I'll keep thinking about the "why" and get back to you.

I do think that this story has interesting pragmatic implications. If a healthcare provider approaches patient interaction in this spirit, it seems that he/she would be prepared to address the complexity of the situation and provide treatment with minimal judgement and/or preconceptions.

One last thing... I have a question about the story of the mind being inside the brain... It seems like we are just taking it for granted that the mind is a production of the brain. What is the evidence that the mind is actually a production of the brain? I know that there is considerable evidence for the physiological basis of emotions, but what about thoughts/ideas and the notion of the self?

It seems like this might be in the itinerary for next week... but I'm definitely curious to hear. Who says neural firing causes thoughts? Why not thoughts causing neural firing? I know this is an old (almost cliche) issue. Has it been answered and I'm just unaware of it?

I'm not sure this is the

I'm not sure this is the evidence that you were looking for, and it is certainly not all-encompassing, but through studies with monkeys, we can alter their perceptions of "reality." Let me explain...

If you can find, through single cell recording, a brain cell in a monkey that responds particularly well to faces, and then to show that monkey a picture of static (i.e. there's not really anything there but random black and white pixels) while simulatneously exciting that cell, the monkey is more likely to respond that they see a face.

There are more examples of a change in brain activity causing a change in perception/thought, though I don't have a list. And, no, this doesn't "prove" that ideas don't cause neurons to fire (instead of the other way around) but I think that there is much more evidence showing that the brain is indeed the seat of the mind than there is for the mind being elsewhere and somehow effecting the brain/body.

~Laura

Monkeys, thoughts, brains

Microstimulation of

Microstimulation of inferotemporal cortex influences face categorization

Seyed-Reza Afraz Roozbeh Kiani & Hossein Esteky

Nature 443, 598 (2006)neural firing, meaning, thoughts

Agree that illusions are one set of observations relevant to the "nothing has meaning besides the meaning the brain gives it" story. There are for me a variety of others at least some of which I hope we'll get to. But looking forward to your further thinking about what makes it an appealing story for you. And agree it has "interesting pragmatic implications," also to be further explored.

And yes, of course, we'll want to talk more about including "thoughts/ideas and the notion of the self" in the brain, and be sure we know what kinds of observations support that story as well. "Answered"? No, of course not. But there are indeed relevant observations since, for example, Descartes (some in the Calvin and Ramachandran articles), with more appearing every day. Can thoughts affect "neural firing"? Yes, indeed, precisely because they seem to be "neural firing" (which helps to clear about a little problem with dualist approaches, how do immaterial things affect material ones? and vice versa).

tension

mental health: semantics, philosophy, and practice

By outside our perception I

By outside our perception I meant simply that we can choose to accept things as Truths, but can't make the argument that these Truths, no matter how many observations support them, are definitively TRUE. The motivation to move forward does not depend on Truth or reality, otherwise I don't know if I would ever get anything done, but rather focusing on the idea that our reality is only our personal reality when trying to solve a problem or dealing with a question only brings about more questions. I think there is absolutely space for philosophy in a discussion about mental health, but how much time and guesswork should be spent on it is questionable...

A Little Philosophy?

I think that discussing a little philosophy is useful in this class. The outlook one adopts, whether constructivism, constructive realism, or realism will affect one’s aims. Similarly, the perspectives of multiplism, pragmatic multiplism, and singularism are relevant. These concepts or principles influence the goals and methodologies of interpretation in art, science, and all other human endeavors. By studying neuroscience and medicine, we are attempting to interpret the brain and mental health.

It is a matter of philosophy whether or not you believe that there really is an empty table in the room. This philosophy will allow you make certain interpretative claims. If someone doesn’t think there is a table in the room, then you can diagnose a problem with their brain or nervous system. As a realist singularist, it seems, to me, to be easier to set non-arbitrary norms. As a constructivist singularist, you might be able to set the same norms, based on consensus. However, this consensus is subject to the counter arguments put forth in the McDermott and Varrenne paper.

Multiplists face a great challenge determining admissible criteria for interpretations. Multiplist ideals may be more inclusivist in nature. These criteria may be open to the some criticisms as the singularist constructivists. They may also lead to an anarchy of interpretation or what we called the soft and fuzzy definition in class. The philosophical perspective can help inform our arguments and take our thoughts in new and interesting directions. Some of those places, we have already visited in class, but there are many more.

Interesting Observation?

ambiguous figures: what alters what is perceived ....

Those who help others - trained to alter perception....

Last semester, I remember having much difficulty changing the direction of the blinking dots. However, last night, I changed the direction with much ease. In other words, I was able to alter my perception.

Going back to what Julia said before about those who "help" others, I think this is very relevant. I think psychologists or 'those who help others' are trained to readliy see all different perceptions (like how I was suddenly able to see the dots go in all directions) and to expose their patients' brains to all the different conformations of perception.

I completely agree with Paul

I completely agree with Paul and Julia: psychologists are trained to see all different perceptions, as we are able to categorize and interpret incoming sensory information.

However, after thediscussion in class, I feel that I’m really confused…

If we perceive things differently from one another, does this mean that there is more than onereality? Are we, in some ways, prisoners and only able to see the shadows of a reality, like the men of Plato’s cave? Do we call reality something that is not? How would we be able to recognize the sources of the shadows?

Mental health and reality, multiple worlds

Maybe there aren't any "sources of the shadows"? Maybe "Ambiguity and uncertainty are not ... the ripples of the imperfect glass through which the brain tries to perceive reality. They are instead the fundamental "reality", both the grist and the tool by which the brain (and, hence, all humans, you and I among them)" constructs its "reality". In this case, there is indeed "more than one reality", or at least more than one world ....

"In what important but often neglected sense are there many worlds?" asked the philosopher Nelson Goodman. Maybe philosophy is not irrelevant to thinking about mental health? Would we think and act differently in re mental health if we discarded the presumption that "reality" is out there, and imagined instead that "reality" is no more (and no less) than the commonalities we have so far been able to find in the different pictures/worlds we each have in our brains?

Are psychologist currently actually "trained to see all different perceptions"? Neurologists? Psychiatrists? Social workers? Could they be? Should they be? What would the task of mental health workers be if we took the many worlds view seriously? Would it eliminate any need/effort to alter individual worlds or give new motivations, suggest new methods for doing so?

no one is all-seeing

As a neophyte social worker, I can confidently say that I have not been "trained to see all different perceptions." While one might argue that I could accumulate such knowledge given enough time/experience/mentoring/studing, I have my doubts. Indeed, the very notion that an individual, let alone a whole class of individuals, could succeed in seeing all angles of a phenomenon seems to me to contradict the idea of "getting it less wrong," and to imply the attainability of some absolute truth.

That being said, I do agree that (at least for me) one is helped by being exposed to perspectives, or interpretations, or ways of looking, one cannot (or has not) readily access(ed) on one's own. And good therapists do just that, they offer a summary of observations that helps an individual get unstuck...at least, that's been the case for me. And of course one does not have to be a therapist to do this, though being trained as one may increase the frequency with which one does it (as might being a scientist, a philosopher, or anyone inclined to believe in multiple realities and questions her/his own).

The question whether taking the multiplicity of possible world views seriously would "eliminate any need/effort to alter individual worlds" relates to the "culture as disability" issue. Nevertheless, I do believe that individual world views can be disabling, not (or not only) because they are not taken seriously by others, but (also) because they do not foster what you, Paul, have suggested as a working definition for mental health; they discourage personal agency and cast doubt on the possibility of change. Perhaps the problem in such cases is that the individual takes his/her own story too seriously.

Therapist as story teller

"anyone inclined to believe in multiple realities and questions her/his own ... helped by being exposed to perspectives, or interpretations, or ways of looking, one cannot (or has not) readily access(ed) on one's own"

That appeals to me as a good definition of a mental health worker. In which case, recognizing the constructedness of human experience is an essential element.

"individual world views can be disabling ... they [can] discourage personal agency and cast doubt on the possibility of change. Perhaps the problem in such cases is that the individual takes his/her own story too seriously"

And so could be helped by a "multiplicity of possible world views" perspective? My guess is that this holds not only for "individual" world views but for community/national/cultural world views as well. On the flip side, perhaps in some cases (people/communities/nations/cultures), difficulty in creating a coherent world view might also be disabling?

Maybe the general need is to help keep things moving/evolving, sometimes by emphasizing the availability of multiple stories, other times by emphasizing the usefulness of having a particular working story at any given time?

Yes...and I would add the

thoughts..

Yesterday we talked a lot about dichotomies, and whether or not we felt the need to draw lines. Some people felt like these lines were necessary, that decisions had to be made to make terms and concepts credible. My problem with this is, even if in the moment, we can make some kind of line, how useful will that be? I think it's like observations being true up until this point- these lines may be true, up until this point, but tomorrow, they may be false. Is it worth it to spend so much time searching for lines to be drawn that can just as easily, with just one exception, be proven false, or should would be looking for things we can rule out, things we can say are already false, so we can make progress through observations that, once proven false, will always have that falseness to it?

Another thing I was thinking about, was with therapy, there is often such a stigma associated with going for help. I started to wonder how necessary therapy actually is- maybe (and I'm sure it is) an idealistic approach to think that maybe, everybody, with all of our problems and issues, is like a puzzle- maybe, we can help ourselves by helping others, just talking and trying to understand the other person can maybe help us reflect on our own troubles, and knowing that they will do the same in return- maybe that's all that is really needed, at the base of this idealistic world. Maybe the need for therapy and drugs and whatever else is what happens because we can't create, or act out this kind of altruistic world.

I would like to think that

mental health and crossword puzzles

I think that

I think that instead of trying to understand their patients, therapists are trying to help their patients understand themselves. I think it is true that we create our own realities, and what really matters is not the “actual reality” (or whether that even exists) but our perception of reality because this is what is real to us. The problem with this is that if we end up in a pattern where we are percieving reality in a way that is detrimental to us it is really hard to break that pattern on your own. Hopefully a therapist could help you take a step back and reframe your perception.

I guess what I was trying to say in class about an “actual reality” is the idea that when we perceive something we bring to it everything we have experienced before. When I look at a table, I am not just seeing that table- I am comparing it to previous tables I have seen, I may be reminded of a memory that had a table in it, etc. Our perception is not objective. I view “actual reality” as unbiased reality, a concept that cannot actually exist.

Mental health and the brain: from meaninglessness to meaning?

Mulling in particular the idea that everything we see (hear, taste, feel) is inherently "subjective," ie dependent on the idiosyncracies of our own distinctive nervous systems and their particular forms of construction. And that science (among other things) is an effort to achieve some degree of "objectivity," in the sense of finding/creating commonalities across our distinctivenesses (see The objectivity/subjectivity spectrum: having one's cake and eating it too?). Its an intriguing notion that "reality" is not the starting point for science. That it begins instead with the variety of different subjective/personal understandings and that it is from the interaction of those that "reality" is brought into existence, that "objectivity" and "reality" are actually stories that derive from social interactions, from the effort to find commonality.

Maybe "mental health" is in some ways the same thing? Not something that is a given that we try to achieve, but rather something that is brought into existence and continually revised by our efforts to find commonality in diversity, not only between people but within ourselves? Maybe we are less similar to each other than we sometimes think, and less coherent internally than we might like to believe? And perhaps those things, rather than being failings, are actually what drives the ongoing process of "getting it less wrong" (as a basic incoherence or randomness drives both evolution and the evolution of the universe?).

What all this would seem to imply (if one took the story seriously) is that neither we (nor biological evolution nor the universe) has a fixed goal any more than we (or they) have a coherent starting point. We (and they) have randomness (meaninglessness) as a driving force that causes new things to be created. And from those new things, and our observations of them, we create meanings as well as understandings, objectives, and goals. And we continually test and revise not only our understandings but also our objectives and goals both by new observations and by comparing them with those of other people. And so we evolve/change, based not on any absolute standards but rather on "getting it less wrong" by whatever local standards we have so far developed. The "law," as Oliver Wendell Holmes argued, is not how we are supposed to behave but rather a summary of what we have so far discovered are ways to behave that work.

Maybe all that provides an explanation for our difficulties in defining "mental health"? Its a work in progress, and necessarily starts from a fundamental subjectivity, one that it can't escape without losing its distinctive reason for being (unlike classical physics). And maybe that makes our course not only a theoretical exploration of "mental health" but a practical one as well? In wrestling with the meaning of "mental health" we're not only creating new meaning for it but also doing so in a way that provides us all concrete experiences with a particular way to get it less wrong, one that involves finding/creating coherences within and among ourselves.

Is the brain really big enough to do all of those things? To accept both left and right (objective and subjective, mind and body, the personal and the social, health and illness) rather than choosing between them? And to do so in a way that is productive rather than mushy? To start from meaningless and create meaning? And then challenge the meaning to create new meaning? And to find meaning in that process itself, both individually and collectively? We'll see ...

Ballerina Optical Illusion

Here's the illusion I mentioned in class... Get a bunch of people in the room and poll to see in which direction she's moving (I'd bet it's not the same for everyone!) Looking at her foot seemed to help me get her to switch and eventually you learn to get her to switch back and forth at will (very cool when you can keep her from doing a full revolution and just keep her switching back and forth three or four times...)

http://www.maniacworld.com/Spinning-Silhouette-Optical-Illusion.htmlas requested...

Post new comment