Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Brain's Constructions and Deconstructions of "Reality"

informed guessing and beyond

Recent General Readership Articles

|

What one sees (or hears or feels or tastes of smells) is ... reality? Or a construction of the brain? A construction that might be different if the brain were different? And so could in fact be different in different individuals with different brains? And different for the same individual at different times? The more we learn about the brain, the more it appears that "reality" is indeed a construction of the brain. A disconcerting idea perhaps, one that challenges a whole host of age old assumptions and practices for many people. But the idea is also one that can help us to better understand ourselves and our relations to each other and to the world around us. And one that can give us an enhanced ability to play a significant role in our own lives and in the universe of which we are a part.

Perceptual "Illusions"

"Staring at a pattern meant to evoke an optical illusion is usually an act of idle curiosity, akin to palm reading or astrology" ... but its also entrancing to most people. And with good reason. "Illusions" provide us with a window into how our brains work. And the more they are studied, the clearer it becomes that brains have been designed (by evolution) not to discover "reality" but rather to make the best sense they can at any given time of inputs that are ambiguous, that might in principle be interpreted in any of an infinite number of different ways.

Given this ambiguity, what we perceive is not "reality", but rather the brain's best guess, an informed best guess, of what is out there that is meaningful to itself (and us). Everything we perceive is such a guess. "Illusions" are just special cases that help us to understand what the brain is using to make that guess, what makes it an "informed" guess. And that understanding, in turn, points us to ways we can move beyond our existing guesses to "less wrong" ones.

Informed Guessing: An Old Example

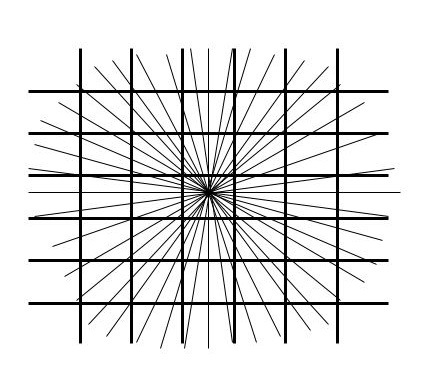

A large class of visual illusions reflects a tendency of the brain (in all senses, not only visual) to pay more attention to changes in input signals occurring over space and/or time than it does to the absolute values of those signals. As a consequence, one's perception of the brightness (as well as the color) of an object is heavily influenced by other objects in the scene one is looking at (as well changes from what one was previously looking at). This can yield quite dramatic changes in both the color and the brightness of particular objects depending on their spatial and temporal context (cf. Making Sense of the "Picture in the Head").

Why isn't the brain organized to show us things "as they are", instead of making their appearance dependent on other things? In what sense is paying more attention to changes than to absolute values a "best guess"? At least a partial answer to that question involves recognizing that the light reaching our eye from any given location depends not only on the properties of the object at that location but also on the properties and location of whatever is illuminating it (see Tricks of the Eye, Wisdom of the Brain). If our perception of objects depended only on the light we get from them, their appearance would change with every change in the illuminating source. A rose would look quite different in the morning than it does at noon or in the evening. Comparisons in the amount and character of light coming from different objects are much less sensitive to variations in the source of illumination ("a rose is a rose is a rose"). By paying more attention to comparisons than to absolute values, the brain is guessing that what is out there are "objects", things that have borders and stay pretty much the same from moment to moment. For most purposes, its a pretty good guess. For others (like if you want to know what fabric will look good on the sofa in your living room, or how a website will look to someone who is "color blind"), it pays to keep in mind that the brightness or color of something, like other aspects of perception, is always a guess. To put it differently, looking at differences is "useful" in some situations and less so in order. It creates stable order in what might otherwise be a less comprehensible fluidity, but in doing so it presumes the usefulness of certain features that may not be useful in other situations.

Informed Guessing: A New ExampleOne might perhaps better say that "the brain's inclination to make guesses about the future creates many common illusions". Some people might be disappointed that there isn't evidence here that the brain can actually "see into the future" but its more than interesting enough to discover its apparent efforts to do so and how those seem to impact on what we perceive.

|

|

Its an intriguing and not at all farfetched idea that in trying to make sense of ambiguous input the brain would tend to try and anticipate future appearances rather than generating perceptions of "things as they are". We do not normally sit stationary in a stationary world but instead typically are in motion in a world that itself may be continually changing. Interpreting signals in this context gives us a set of ways to make sense of the world that we wouldn't otherwise have, as first compellingly pointed out by J.J. Gibson. Moreover, neural processing takes time (see Time to Think), enough so that by the time a perception is created it may well be out of date.

Perhaps then the message is that the "informed guesses" that our perceptions are based on include not only some presumption that there are reasonably stable "objects" in the world but also on a presumption that one's relation to them is likely to be changing over time in somewhat predictable ways. Here too, its useful to know that what we perceive is an informed guess, but always a guess. Often it may be advantageous to anticipate what will be seen, but some times one might want to know what is now. And for that one needs to know that what one sees might be different if evaluated in differently informed ways (use a ruler to verify the squares are in fact flat squares).

Could We Do Without Informed Guessing?But what's "real"? What would the world look like if one didn't make informed guesses? Supposing one could itemize all the ways that what we perceive is constructed, all the informed guesses that the brain makes, and then remove them. What would things look like? That question was posed by a student in a class on neurobiology and behavior I taught this year, and another student suggested the answer: "I think reality would be a very noisy place". And that may indeed be the best answer one can provide. "Eliminative reality" may be mostly randomness, waiting to have small statistical regularities noticed by a brain capable of best guesses (see Eliminative Reality and following comments/links, and Chance in Life and the World). Maybe "meaning" is what we make of small regularities in noise?

Who's Doing the Informed Guessing? and Why Should One Care?

Clearly there are things being revealed by illusions that, as suggested by how entrancing they are, teach us things about ourselves and our relation to the world around us. That we don't know about these things until we discover them through illusions also illustrates a more general important lesson about ourselves. The "informed guessing" is being done by processes in our nervous system of which we are largely unaware. Not only do we not know the basis of the informed guessing, until we notice and study it, but we aren't in fact usually aware that what we see involves guessing at all.

Clearly there are things being revealed by illusions that, as suggested by how entrancing they are, teach us things about ourselves and our relation to the world around us. That we don't know about these things until we discover them through illusions also illustrates a more general important lesson about ourselves. The "informed guessing" is being done by processes in our nervous system of which we are largely unaware. Not only do we not know the basis of the informed guessing, until we notice and study it, but we aren't in fact usually aware that what we see involves guessing at all.

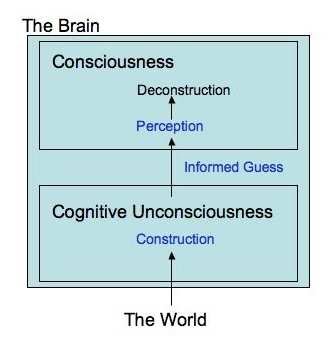

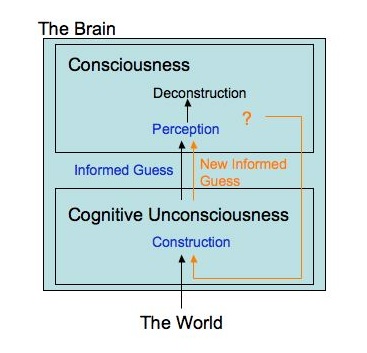

This is because our brains consist of two relatively distinct regions. One, the cognitive unconscious, makes informed guesses and delivers them to the second, conscious part, which supports our awareness of what we are seeing while knowing little or nothing of how what we see has been constructed. By trying to explain illusions, wondering how we come to see what we see, we can, using consciousness, deconstruct the process of perception, gaining a useful ability to appreciate things in ways other than those made immediately available by the informed guessing of the unconscious.

The "Bayesian Brain" and "Free-energy"

Just as we tend to see the world as consisting of clear and certain objects rather than a sea of ambiguity, brain researchers have tended to think of the brain itself as functioning in terms of a large and complex but ultimately machine like set of clear and certain processes. More recently, however, it has begun to be suggested that there is significant indeterminacy, and hence ambiguity, within the brain itself, and that brain function might be better understood not as a set of cogs and wheels but rather as an information processing system that continually and somewhat unpreditably generates and updates probabilistic descriptions not only of the world but of its own function as well.

"Making predictions and evaluating them seems to be a universal feature of the brain."

Thomas Bayes was an eighteenth century mathematician and minister who formalized a method of continuallly updating guesses based on new observations, without the assumption normally made by statisticians (and the rest of us) that uncertainty reflects imperfect information about an actual state. Bayes instead assumed only that all we ever know is the likelihood of something, and all we can do is to update that likelihood by new observations. Hence, the thought that it might be productive to look into the extent to which our brains are actually "Bayesian" inference machines.

Still more recently, it has been suggested that both interpreting sensory input and learning about the environment can be thought of similarly as processes of reducing the likelihood of substantial violations of predictions made within the nervous system or, roughly, as assuring that the nervous system has at all times reasonably good models of the world. In terms of trying to characterize brain function in the broadest possible terms, there are intriguing parallels between this and the minimization of free energy in chemical and physical systems.

Whether either the Bayesian or free energy formalisms prove in the long run to be productive routes to better understanding the brain, it seems clear that our brains are doing a lot more guessing and updating than most of us (neuroscientists included) have imagined in the past. Perhaps, as suggested, there is in fact nothing more than informed guessing, no describable "reality", no actual there there (at least nothing more than noise with some statistical regularities) without at least some informed guessing. Let's see whether taking that notion seriously takes us anywhere.

Ambiguous Figures: Beyond the Limits of Informed GuessingIllusory figures provide a window into the informed guessing that goes on in the brain, and suggest that there is an underlying ambiguity in making sense of the world that makes informed guessing a useful feature of perception. Ambiguous figures give us a more direct look at the underlying ambiguity, and at the limitations of informed guessing. They also serve to further strengthen the argument that consciousness gives us the ability to move beyond the informed guessing that our cognitive unconscious provides us.

|

|

Like illusory figures, ambiguous figures can be enjoyed and then disregarded as "special cases" of perception, as, perhaps, amusements created by artists lacking any more general significance. Once one gets interested in them, however, they seem to turn up again and again, and in lots of places where there is no artist involved. In fact, one can find multiple ways to see almost anything (everything?), if one puts one's mind to it.

If one's in a hurry, and needs to act now, its nice to have the cognitive unconscious provide one an informed guess. That's a snake, or a car bearing down on me, so move! But we don't always need to act immediately. Sometimes it can be useful instead to reflect on what we're seeing, and to see what other kinds of informed guesses our cognitive unconscious can come up with. One might even suggest that that is a primary function of consciousness, not to decide what is actually there and act on it but instead to withhold judgement long enough to give the cognitive unconscious a chance to come up with some alternative informed guesses. Maybe, in fact, knowing that what one sees is no more, and no less, than an informed guess and making use of that in one's behavior is an important part of what we mean by personal responsibility or free will? One can use informed guesses but not be a slave to them?

If one's in a hurry, and needs to act now, its nice to have the cognitive unconscious provide one an informed guess. That's a snake, or a car bearing down on me, so move! But we don't always need to act immediately. Sometimes it can be useful instead to reflect on what we're seeing, and to see what other kinds of informed guesses our cognitive unconscious can come up with. One might even suggest that that is a primary function of consciousness, not to decide what is actually there and act on it but instead to withhold judgement long enough to give the cognitive unconscious a chance to come up with some alternative informed guesses. Maybe, in fact, knowing that what one sees is no more, and no less, than an informed guess and making use of that in one's behavior is an important part of what we mean by personal responsibility or free will? One can use informed guesses but not be a slave to them?

Impossible Figures: Beyond the Limits of What Has Been

Deconstructing the process of perception using consciousness makes it possible not only to go beyond immediate informed guesses about the nature of things we say but to create things we would not otherwise perceive, to be creative. Visual artists have over centuries acquired great skill at using the brain's propensity to make informed guesses to cause viewers to see things other than what is actually there (a sense of three dimensions in two dimensional paintings for example). But one can, in addition, create representations of things that not only are not actually there but could not in fact be there. Escher is the best known of a large number of artists who create such impossible figures. To do so, they create images so as to cause the brain to make a best guess at one location in the image and a different and incompatible best guess at a different location. The upshot is that instead of their being multiple best guesses for the image as a whole, there is no satisfactory best guess at all. No single informed guess suffices for the entire picture. To put it differently, perceptions as informed guessing may be the foundations of our understanding but we are not limited by them. We can create things that go beyond what we have perceived and, in so doing, bring into existence in our world things that have never previously existed and would not but for our construction of them.

Deconstructing the process of perception using consciousness makes it possible not only to go beyond immediate informed guesses about the nature of things we say but to create things we would not otherwise perceive, to be creative. Visual artists have over centuries acquired great skill at using the brain's propensity to make informed guesses to cause viewers to see things other than what is actually there (a sense of three dimensions in two dimensional paintings for example). But one can, in addition, create representations of things that not only are not actually there but could not in fact be there. Escher is the best known of a large number of artists who create such impossible figures. To do so, they create images so as to cause the brain to make a best guess at one location in the image and a different and incompatible best guess at a different location. The upshot is that instead of their being multiple best guesses for the image as a whole, there is no satisfactory best guess at all. No single informed guess suffices for the entire picture. To put it differently, perceptions as informed guessing may be the foundations of our understanding but we are not limited by them. We can create things that go beyond what we have perceived and, in so doing, bring into existence in our world things that have never previously existed and would not but for our construction of them.

|

|

Drawing by Roger N.Shepherd, Mindsights,

|

"It is sometimes said that advances in empirical science not only necessarily alter our sense of humanness but invariably demean it ... I ... see the current and projected impact of empirical research on the brain in a quite different light."

Illusions, ambiguous figures, and impossible figures are fun, but they are more than that as well. They provide windows into how our brains work. And, in so doing, they help us see not only where our perceptions of "reality" come from but, even more importantly, the role we play in our constructions of reality and the capability we have to move beyond any particular construction. Yes, we may have to give up the idea of a fixed "reality" that we aspire to discover. But we are offered, to replace it, a sense of ourselves as active participants not only in making sense of our world but of shaping it as well. That is, it seems to me, not a bad tradeoff. To understand the brain is not to demean humanness, but rather to recognize that we have a continuing capacity to create in new ways, that any particular understanding is not an end but rather a foundation and resource for new understanding. No matter how much we learn about the brain (and the world) there will always be more to learn. The answer to the question "Is it possible to capture all the workings of your brain in one simple equation?" is a loud "no", because in learning we necessarily create new things to understand.

Comments

Hollow Mask Illusion

Hollow Mask Illusion Fails To Fool Schizophrenia Patients (Science Daily 17 April 2009)

Try as I might, I absoultely cannot distinguish a difference between the two faces in the article...

Brain's construction and disconstruction

On 13th September, 1848, 25-year-old Phineas Gage and his crew were working on the Rutland and Burlington Railroad near Cavendish in Vermont. Gage was preparing for an explosion by compacting a bore with explosive powder using a tamping iron. While he was doing this, a spark from the tamping iron ignited the powder, causing the iron to be propelled at high speed straight through his skull. It entered under the left cheek bone and exited through the top of the head, and was later recovered some 30 yards from the site of the accident.

By 1st January 1849, Gage was leading an apparently normal life.

From what I can see in the drawing the tamping rod is at least one inch thick

hollow mask illusion reply

Laura, those two photos are of the exact same person at the same time. There is only a subtle difference in the angle that each photo was taken. Pretend the two images are one Magic Eye picture and unfocus/cross your eyes. If you get it right (e.g., if you can "free fuse") you will see a third image appear in between the two that are actually there and that 3rd image will look like it's in 3-D. this image is actually special because when it's seen as a 3-D image, it's actually made to be inside out. The article you linked to was a summary of a publication suggesting that people with schizophrenia will be more likely to correctly see the face as being inside out (like looking at the inside of a plastic Halloween mask - called the hollow mask illusion) where as those without schizophrenia will see the face as being convex, as faces normally are.

See Photos Which Are Not There

In a specific case, a girl Child of 15 years was scanning the mobile of her uncle. Suddenly she screamed and told her mother that there were some pictures of her mother in nude. She gave discription of the clothes and place also.

There were no such photographs in it. She had seen her mother in compromsing position or have heard them making love. How to handle such situation. What is this condition and how to treat it??

Serendip Pingback

[...] This page has been linked to from Science and art, art and science, and .... life | Serendip's Exchange

[...]

Mirrors

Here's an intersting read exploring the brain's interpretation of mirror images and bringing up some of the realities we have discussed in theis years BBI. It also mentions how one's constant reflection can affect human behavior in such a way as to minimize cheating, social stereotyping in a work enviornment. Should school's try to build better work ethics and morals by installing mirrors all over their classrooms? Or implement something similar?

Other illusions?

Paul thank you for that

Paul thank you for that interesting and illuminating post:

As you know from our conversations, my interest is how we apply these basic and profound insights in the world of education. Nowhere in our education system do we address the mind and brain as the window through which we experience the world. We may study the brain in a biology class and we may study the mind to a certain extent in a psychology class, but these tend to be abstract investigations. To the extent that we study the mind and brain at all we study them much in the same way that we might study the geography of Eastern Europe or the history of World War II. We teach information. We do not help students engage in an investigation of their own mind.

As you pointed out illusions are fascinating because they offer such a strong experiential window into the workings of the mind. Illusions force us to question the nature of reality. They force us to think about the role that our mind takes in constructing reality. Illusions are useful teaching tools because they jar us out of the comfortably constructed perception of reality that we have in a given moment.

I find that when teaching about the mind illusions serve as a perfect way to set the tone for the class. Seeing an illusion wakes up the students, it’s almost like an on switch for the minds. At the same time the students get a jolt to their perception system and motivation to explore what is actually going on. This makes the rest of the class much more creative and interactive.

In a way I think it’s very similar to using a joke at the beginning of a speech. Playing with people’s expectations gets them to wake up and pay attention. It’s a signal to the audience that says this is new and important so pay attention. I actually thing that humor is another great topic to explore in any experiential mind class. What is humor? Why do we find certain things funny? How is humor used in social interactions? These are all fascinating topics and could be a great way for many students to investigate their own minds. Not to mention that discussion and presentations promise to be funny to boot.

So what’s the next step? Illusions are great, but where do they take us down the road? I think that the main question is: how do we teach about the mind experientially? Every one of us has a mind. Each of our minds is different and yet we share (construct) a common reality. What kinds of experiences can we create for students that help them discover the nature of their own minds? How can we create a lifelong dialogue based on curiosity and investigation?

These are subjects that I think a group of teachers would be in a great position to explore.

Here's a humorous idea for education

Illusions: the next steps?

Pleased we will have a chance to explore, together with other teachers, where "illusions take us down the road." Yes, illusions can wake people up, and I fully agree that (as with jokes) something more is needed.

What about the idea that a useful direction next direction is ambiguous figures (as opposed to illusions in general), since they seriously challenge the notion that the best we can do is "share (construct) a common reality." Input is generally ambiguous and we all see it differently ("each of our minds is different") UNTIL we start looking for a "common reality." Illusions help us to appreciate the constructedness of what we perceive. Ambiguous figures go a step further, to help us appreciate that "common reality" is actually a limitation of what we construct/perceive that can be relaxed.

And, one step further along this path, impossible figures can help us to appreciate the usefulness of seeing things in terms of things other than "common reality", ie the potential benefits of seeing things in new ways, unexpected by either ourselves or other people. That the mind is fundamentally built not to represent something outside but rather to create things, some of which may be old and others new .... is that not something about "the nature of minds" worth discovering? something that would not only support but encourage a "lifelong dialogue based on curiosity and investigation"?

Looking forward to further exploring this and other paths from illusions out of similar motivations.

What about Control?

The concept of choice is an interesting one. As a child, I was taught that choice is a combination of agency, creativity, and perception. There is a poster in a teacher's class room in my high school that espouses a similar idea. It argues that attitude, not choice, is capable of affecting 90% of our lives. The other 10% is out of our control. The poster over simplifies the relationship between choice and control.

I think that the connection between choice and control should be explored in terms of curriculum and pedagogy. Choice does not entail complete control. So we should allow students a significant amount of choice and not sacrifice control of the classroom. This technique might be modeled in open-ended inquiry activities. Conversely, can a teacher control a classroom? Not completely. The teacher can insist on covering specific material, but not on student comprehension.

Optical Illusions and Evolution

Understanding the process of learning and memory some more and revisiting the differences between human being and lowered leveled animals, I better comprehend how the neuronal discrepancy between the two has allowed for the human race to reign superior. Our mental capacities give us the privilege to form multiple interpretations of things in the world, equipping humans with the ability to, in a lot of ways, dispel the uncertainty found in ambiguous situations. The main reasons why we (the human brain) can decipher ambiguous perceptions is because of the fact that we are so highly trained in recognizing and, more importantly, remembering patterns that, when found in a certain combination, renders a conception of the world which we then act upon. On an evolutionary level, this is incredibly advantageous because it gives us humans the ability to differentiate between that which is and is not threatening to the individual. One clear- cut example is when camouflaging is involved because it can easily by countered with our brain’s conscious deconstruction of perceptions of the environment. On the flip side, we humans have been able to manipulate devices, both natural and otherwise, to create ambiguous situations to both lure our prey to us and confuse our predators.

Diversity is equally good

The notion that several possible interpretations of the world are “equally good” greatly supports encouraging neurodiversity (as well as the many other forms of diversity) into the educational experience, i.e. schooling. (To quote a student from a Neural and Behavior Science senior seminar course again) “…it’s important to celebrate what makes us different so that we can integrate those differences into our ways of thinking.” This I feel is definitely true because just as Grobstein says “sometimes there is more than one way to do it,” which can easily apply to both the teacher’s pedagogy and the student’s participation in the class. For the value found in our cognitive unconsciousness, producing alternative informed guesses provides more and more creative stories and more metaphors to both challenge and understand the world we live in.

Turning the Tables

My response to this interesting new site was conditioned (as all responses are conditioned) by the context in which I read it. I'm in the midst of co-crafting a new College Seminar @ Bryn Mawr on choice (for a preview, see Food for Thought: The Omnivore's Dilemma). Two of the books we are considering for our syllabus are

* Barry Schwartz's five-year-old The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less--which begins with the presumption that "the desire to have it all and the illusion that we can is one of the principal sources of torture of modern affluent free and autonomous thinkers," and argues in favor of all of us become "satisficers," making do with overwhelming choice by limiting our choices; and

* Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein's brand-new Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, which argues that we can all learn to become "choice architects." This means managing our wealth of choices by acting in accord with the principles of what they call "libertarian paternalism," a kind of liberty-preserving attempt to influence choices in a way that will make choosers better off.

This latter book is very much about public choices--Thaler and Sunstein think about how to re-design credit markets and social security, how to increase organ donations and save the planet, how to improve school choices and privitize marriage. The underlying presumption is that there is, in each of these cases and in dozens of others, one best choice.

It's in that context that I' m finding this description of our unconscious process of "informed guessing" so intriguing, especially its presumption that the many different interpretive choices open to us are all "equally good," that among multiple guesses "there is no satisfactory best guess at all." Schwartz, Thaler and Sunstein all presume that the goal is to narrow our choices, to reduce our options, in order to make the best decision we can, for ourself and others; in contrast, this current essay on "Illusions, ambiguous figures, and impossible figures" insists on ultimate undecidability, given the lack of any reference to "reality" to adjudicate correctness.

In insisting that ambiguity and uncertainty are not fungible, but fundamental, this essay seems to me to function as background for the positivist choice work of Paradox and Nudge. And it is a ground neither of them acknowledge. For example, Thaler and Sunstein begin with the famous "turinng the tables" optical illusion (included among the Ambiguous Figures featured on Serendip), but their focus is on our misperception, our inability to see that these table tops are "actually" identical in shape and size. From this mistake they craft a weighty way of publicly correcting our errors....

...rather than recognizing that "in learning we necessarily create new things to understand."

Speaking of which...I find it ironic to see "rose is a rose is a rose" used as an example of the invariant. When Gertrude Stein first wrote that sentence in 1913, it took the form of "Rose is a rose is a rose"-- the first "Rose," in other words, was the name of a woman. With that turn, Rose becomes, of course "not-a-rose," not the same-as @ all....

Deconstructively,