Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Brain, Education, and Inquiry - Fall, 2010: Session 8

Session 8

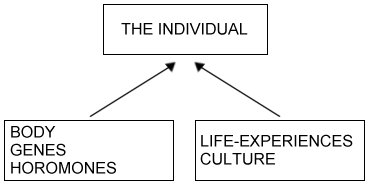

Braiding three lines of inquiry

- our own experiences of education in relation to other peoples'

- doing our own experiment in co-constructive inquiry

- exploring usefulness of insights from studies of brain for thinking about education

Issues of own experiences in re other peoples' (from first web papers)

- importance of encouraging "creativity" in classroom (vs rote learning) - Abby Em, Amenah, Angela Digioia, bennett, evren, FinnWing, jessicacarizzo, kgould, kwarlizzie, LinKai Jiang, skindeep

- importance of achievement gap, standardized testing, acculturation - D2B, eledford, epeck, L Cubed, Liz J, ln0691, mmc, simonec

Exploring a contrast/difference:

Can we find new stories about the objective of education, individual and/or shared? (Enuma, Emily, Abby, Maheen, LinKai; Elana, Christina, Angela, Bennett, Devanshi; Liz, Ellen, Evren, Kate, Naa Kwarley; Mae, Simone, Jessica, Lars)

Overall objective: students are respected and, after years later, are able to apply the skills to the current situation. Students have a certain consciousness in the real world; they seek out what is new and unknown to them to expand their knowledge .... Abby, Angela, Bennett, Elana

the goal of education is to create innovators ... Liz, Ellen, Naa Quarley, Evren

Group statement about the current objective of education: Creativity, discipline and utility are not contradictory; they are compatible. There is a basis/ a foundation and then comes the intellectual creativity ... Emily, Maheen, LinKai, Enuma

Teachers should be held to higher standards, and part of that may involve teachers being perceived differently and more appreciated by society ... Lars, Jessica, Mae, Simone

Class is itself an experiment in a particular form of education: co-constructive inquiry

Learning by interacting, sharing observations and understandings to create, individually and collectively, new understandings and new questions that motivate new observations

Depends on co-constructive dialogue, being comfortable sharing existing understandings, both conscious and unconscious, in order to use them to construct new ones. Need diversity of understandings, need to be able to both speak and listen without fear of judgment. Need to see both self and others as always in process, always evolving

"the school she was in, was known to be a 'difficult' school, with 'problem' kids. and yet, the school in itself, with its infrastructure, reminded us both of the schools we attended, in India. - they weren't in the best condition, we didnt have computers much less a computer lab, the teachers were underpaid and the facilities weren't great. yet. our schools were considered one of the best in our cities. and so, we were treated with respect, and intelligence, and people spoke to us like they expected things from us - as a result of which, we learned to work and rise up to those expectations. and i cant help but wonder, how much of the problem we face right now, has to do with this - stereotypes, labels and expectations. if you dont think a child can do something, and everyone around him believes he's bound to fail, one day, he'll learn to believe it too. and whats the point in that? ... skindeep

Breaking off into small groups this evening was excellent. There is a lot to say and hear in class, and being in a small group enabled me to say and hear more depth of perspective, which I really appreciated ... FinnWing

Sign up to try facilitating co-constructive inquiry yourself, individually or in small groups. Email me with names/topic/date preferred. Something on how something about brain does (or doesn't) help think about education. Paper on this topic due 1 November.

Continuing from where we are: from last weeks forum

It's pretty transparently cynical of me, and maybe lazy too, to appeal immediately to our baser instincts – ideally, it be nice if people just "cared about the things that matter," rather than having to have some kind of material incentive. But I also think there's a good chance here to use some of the things that I've learned about the brain to make a less cynical, less reductive claim. It's probably not true that people simply always do things for money, or that money is somehow inherently worth doing, and our brains are hard-wired to stay focused always on making money. The brain, as we've learned, is a system that flexibly and adaptably handles inputs and outputs. It seems reasonable to imagine that there is or could be a way to reconfigure the relationship between conceptual inputs and outputs – we're not stuck with a system that demands that money have a high value. So then the question is how exactly to affect those changes, which is something I think we could explore in class, if we want to ... bennett (and lots of others re teaching/money)

I wonder if what we've learned about the brain would actually encourage us to depriviledge the conscious even more and focus on what the infinitely fecund unconscious is telling us. Not just as a receptacle for "unacceptable" conscious impulses, but rather a free, id-governed (or ungoverened) space, ie sans the negative moral connotation ... jessicarizzo

when the world starts getting wobbly and things seem dreamy even though I'm awake, I'm able to take a deep breath and just know that it isn't the end of the world. I can roll with it. And the events haven't been as bad, or I haven't noticed them as much. I've been slowly changing my reception of and reaction to them. I guess, because of all of this, I am more than willing to acknowledge the brain as a construction, as the world as a construction, of no one, right reality. My experiences with SLE aren't wrong or crazy. They're just another perspective, another reality, another self. And it's helped me develop my own interests and skills and paths. Not all bad, I guess ... kgould

i found this really interesting. the idea that something doesnt need to happen to you for you to be a certain way - just thinking, or rather believing, it happened is enough .... i wonder how we distinguish between what counts as confabulation and what doesnt. when it comes to matters in faith, or matters of consciousness, who apart from the person who has experienced the situation can fairly decide if it actually happened or not? this makes me wonder about people with schitzophrenia, or people who claim they have seen god. it also makes me wonder where then, is it okay to draw the line? because to be functional in this society, people need to be at a certain consensus about what did and did not happen, and what qualifies as an experience, and what does not. how else would we build concepts like morality, law, even education? ... skindeep

see Brain Fiction by William Hirstein, MIT Press, 2006

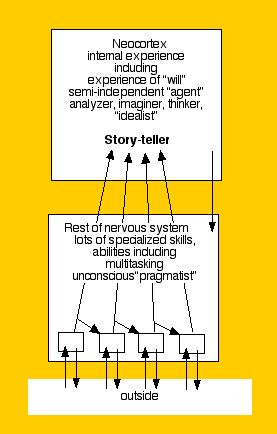

Last class we established that the neocortex is essentially a story-teller. It takes information from all the different parts (that communicate with each other and the outside world) to create a single, coherent story. So everything we know, everything we have ever known is a construction ... But where does that leave us? We can take either end of the spectrum - either there are an infinite number of truths/realties/equally valid constructions or there an no truths at all - but both are equally problematic. If there are no truths then there is no right or wrong and society falls apart. If all constructions are valid, then which ones do we adopt because surely we apply all of them to society (some, for example, might contradict each other but that doesn't make them any less valid). Sure, we can have a shared construction, but then who decides which construction is right and the best one to follow? The majority? The bourgeoisie? The past/the way things have always been? Moreover, if nothing is true, what are we teaching/should we teach our kids? ... Amenah

For group consideration: "if nothing is true, what are we teaching/should we teach our kids?"

Implications for education (to date):

- Brain as loop, active empirical inquirer, can create new things

- Perception, action, knowledge as construction

- Stop presenting understandings as "right," "definitive"; present instead as foundation for developing new understandings?

- Diversity in classrooms an asset rather than a problem?

- Ability to see things in multiple ways a virtue, a desired result of education?

- Inquiry skill is present at birth, rather than dependent on maturation/education

- Acknowledge, make use of distributed/bipartite organization, internal "conflict"?

- "boldness/vision," "choosing ... questions [one] wants to ask, or articulating those questions [oneself]" is related to thought/feeling and neocortex, reflective versus unconscious process

- There is a space between the cognitive unconscious and the story teller that leaves room for change/newness/individual agency

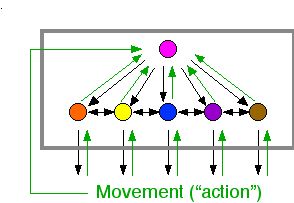

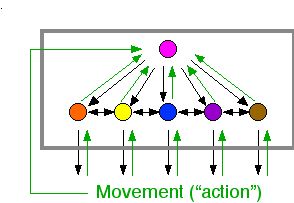

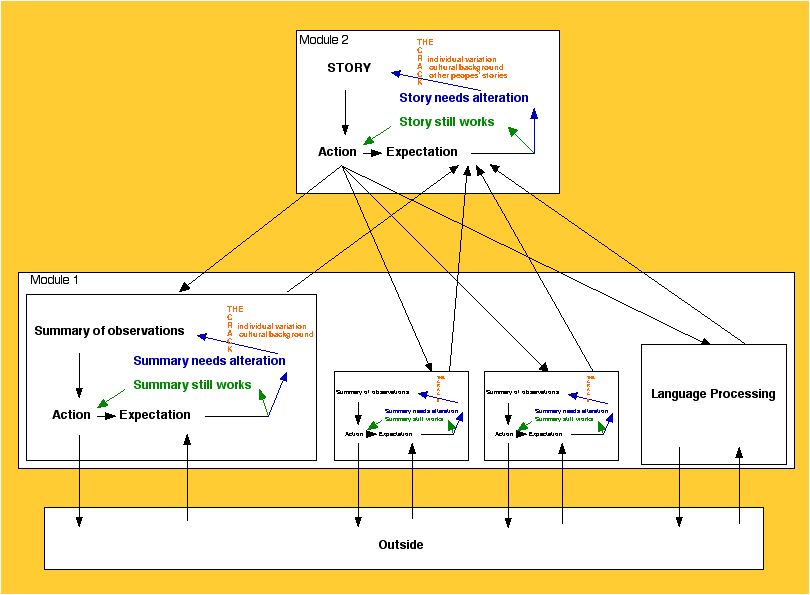

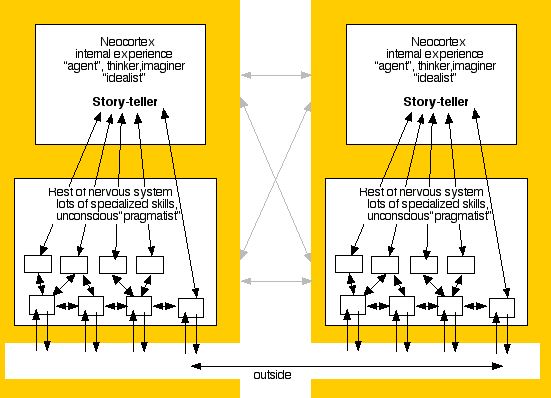

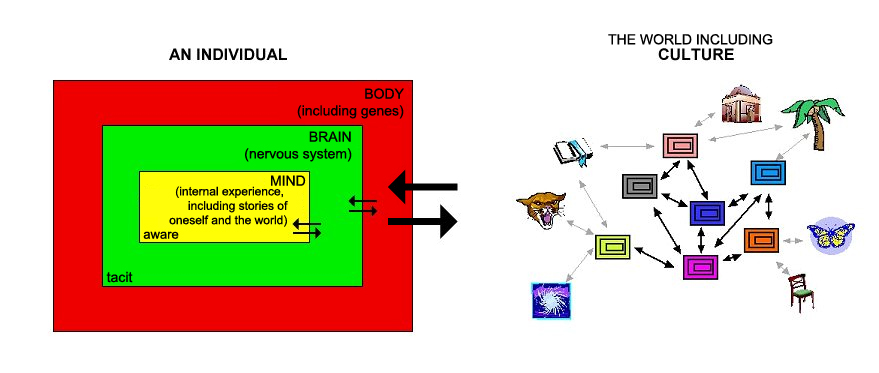

We are distributed systems, constantly using conflicts to generate new understandings

The bipartite brain - adding in the neocortex (where is Christopher Reeves?)

More on bipartite brain

Blindsight, cortical paralysis, dissociative fugue, skilled athletic performance

Dreaming, sleep walking, locked in syndrome

Relevant for thinking about constructedness of world but also of self: pain, phantom limb pain, confabulation

Interactions of cognitive unconscious (Marvin Minsky, Society of Mind) and story teller

Thoughts, feelings, aspirations not parallel to cognitive unconscious but rather derived from it

Emotion, intuition not distinct from thought but a part of it (Antonio Damasio, Descartes' Error)

Internal co-constructive dialogue/inquiry as well as external

Internal conflicts (weight control), added capabilities: to conceive beyond experience

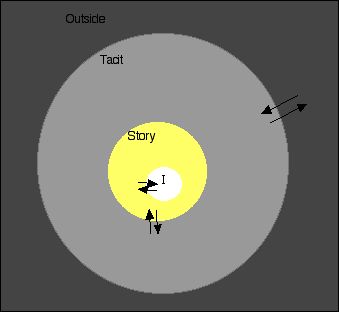

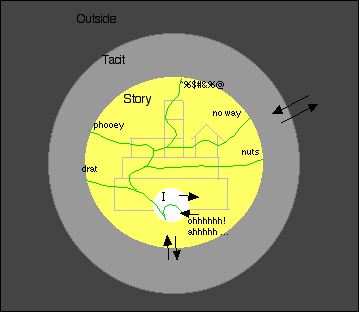

![]()

Constructing a story of the world

- informed guessing and beyond

- some more examples

- and beyond

- creating meaning

- Implications for understanding "understanding"?

Constructing a story of the self and of one's relation to the world

|

|

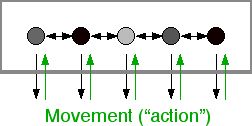

Loop 1 Empirical knowledge generated by conflicts with outside world

Loop 2 New understandings generated by internal conflicts

Revising the conscious

Revising the unconscious

|

|

Loop 3 Interpersonal relations, society/culture, morality: new understandings generated by conflicts between brains

- Culture as disability

- The emotional dog and it rational tail (click on title for .pdf after entering info)

- The moral life of babies

co-constructive inquiry

|

|

The brain uses three intersecting loops to detect conflicts/differences, uses them to create new ways of being, over and over again - The objective of education is to facilitate that ongoing process

Roger Shephard

|

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing - Rumi (1207-1273) |

Your continuing thoughts about all this and its relation to the classroom in the forum below ....

Comments

Great Discussion

This week's discussion is really great.

The question of overarching facts and their place in education, and the role of education in the first place is quite fascinating. I want to chime in to say that I believe that the role of education is to put children (and anyone being educated) in a position to succeed in the way that he or she wants to succeed. For a physicist, learning the theories of forces and gravity in Newtonian physics is crucial for a career in classical mechanics. Yet, learning that it is theory is crucial as well, not only to understand, but to build on current understandings. For someone who wants to be a historian, learning that many styles of writing can appeal to many people is crucial, as is learning how to write in established styles for the times when it is necessary to get a point across in a succinct way. Finally, someone who wants to work in construction should learn how buildings are put together in theory, and also have practice doing the building.

For each person, education should put them in a position to succeed, and also to feel comfortable choosing a definition of success independently. The idea of absolute truth is a spectrum, and when we go too far towards convincing ourselves and others that there is absolute truth, we are also inhibiting and impinging on divergent thoughts that continually enrich our lives.

Need vs. Want

During group discussion there was a small disagreement regarding the needs and wants of humans. Do people need an overarching truth, even if artificially created (since there is no truth), or do they simply want one in order to organize their lives? One may argue that an overarching truth is necessary for our civilization to progress and develop, but how can one define progression and development objectively? Is progression defined by harnessing science to make new gadgets that make lives easier? (Or does technology more often than not really complicate our lives?) Is development defined by making medical discoveries that increase our life expectancy? As amazing as the human brain is, its abilities are finite, which is why people naturally try to categorize everything they encounter. Does this then suggest that having an overarching truth is a need, because the brain's ability is limited and a lack of truth is too much for it to comprehend? Or do we just want a goal in our lives; something to keep us busy as we slowly expire?

Learning through Stories

Eledford and epeck's comments this week really resounded with me and I would like to explore this topic a bit further. When instructors allow children to feel that they have a voice in the classroom and that they already know something about a given topic, they are empowering those children to further explore what they do and do not already know; they encourage critical thinking from a very young age. (Note that I would define a successful education in terms of a child being engaged in the world around them, asking questions, and seeking answers. Over time, they develop their inquisitive sense and begin to form opinions about the world, other people, information that they hear, etc, based on their ability to critically assess whether they agree or disagree with a piece of information. This child--now an adult-- embodies an individual all their own with specific moral and social opinions. As a result of their ability to analyze information that was reinforced at a young age, they are able to contribute their unique ideas and beliefs to society to help others to see/learn information in a new light.) The critical thinking that I did as a child was through hearing stories, whether they be from my parents' or grandparents' mouths or from a book. Stories and storytelling were a powerful tool in my education and I believe that they are underutilized because it's an informal way of learning information. Even though storytelling has been around for centuries, it's a bit too touchy feely for the rigors of academia today. I would argue that storytelling in the classroom could be correlated to better student interaction, discussion, and comprehension of material. As an example, for the last two weeks in class, we broke into small groups to address a question that was posed to us. In both of my groups, we told stories of our own education and beliefs as they related to the question. Stories enable human beings to relate to each other through an emotional connection that is built between the teller and the person listening. After the teller is finished, the listener likely feels that they were actually there for the experiences that the teller was describing. They too would be able to tell the story to another person now. In this way, knowledge and learning are accelerated through the passage of information through the medium of stories. Although the story is latent with the teller's bias, the person listening is able to assess what resounds with them and what does not and why. Because storytelling as a much an art as a science, practice is required and should be encouraged in schools from a young age. Children are full of stories and observations. They need to learn by practicing how to form an opinion and how to express themselves to their teachers and classmates. Respecting their voices through listening and giving value to their stories will build the foundation for these children to become adults who are able to express themselves clearly and succinctly to convey information as well as to critically assess other information that they encounter in the world.

cog. unconscious/conscious

What stuck out to me from last class was the idea that it might be better to teach to students' cognitive unconscious rather than their conscious. If we look at that idea in along side the idea that the cognitive unconscious does not know "truths" and has no concept of the truth, then these two ideas together seem to be saying that in teaching to a student's cognitive unconscious, teachers would not be teaching truths. Instead, teachers would be teaching to a system devoid of truths. If students were taught in this manner, would it matter then if teachers were teaching them explicit truths? or would it matter more how and why ideas are taught and how connections are formed? I do wonder though if it is entirely possible to teach entirely the cognitive unconscious and how such activities would be structured. I feel like if activities were based on teaching to the cognitive unconscious, then the overall objective of a lesson or activity might not be made obvious to the students. Rather than create a checklist of things to learn that is made available to the students, teachers would have to create activities that applied to a certain lesson but have a less obvious objective (at least to the students).

We didn’t/don’t seem to have

We didn’t/don’t seem to have encountered too many issues in finding something to teach out kids if there are no truths. The general consensus seems to be that even though there might be no truths, we can still teach our how to think versus what to think, we can teach them to question and be critical, teach them love, justice and faith, social norms, teach them to learn by having fun and playing games and the like. It definitely seems like we’re moving forward as the class progresses. We’ve considered how, at least to some extent, everything is a construction. And then we’ve also agreed that there are some things that we can teach our kids even if there are no truths. However, my question is how, if it all, we can practically apply this. It sounds good in theory but must be actually applicable to be of any use. It seems to be a huge leap from the way many schools function now (teaching facts that are passively accepted). Ideally, society would be such that an education system like this would just work, but realistically, college, jobs and the way society functions still needs to be kept in mind. Is it possible to bring about the changes we want to see in education without having to deconstruct and rebuild society as a whole?

I'm definitely being

I'm definitely being influenced by the rally this weekend (restoring sanity/fear) - and this is sort of echoing what people said in class about teaching games/fun or love, but maybe the thing to teach kids is rationality. If we can teach them how to understand life in a rational way and look at what is presented as "facts" and what may just be over-exaggeration or even untrue (at least in terms of local truths), they might become rational adults who can work within the boundaries of society, but also know when those boundaries can and should be broken down. Of course, the issue of teaching kids rationality might be incredibly hard and we would first have to agree on what rationality is. I think that if we learned how to be good thinkers, the ideas of (capital T) Truths (like love or kindness) and how to play the "game" well and have fun with life and education would come naturally.

I liked Abby's example of the teacher who taught an implausible lesson and then pointed out that the "facts" he had taught the kids were obviously wrong. Teaching children to really think about everything that is told to them and giving them the tools to decide whether it's plausible or not seems like a good strategy before we get to teaching them our local truths. It seemed from that story that the kids in that teacher's class came out of the class with a more flexible and engaging view of education - the idea that they could still be in the system and succeed, but could have fun with it and really investigate what they were told.

Elana I always seem to find

Elana I always seem to find myself commenting on your posts...

This is such a critical comment, I think. Reading the news really "blows my mind" these days because of how easy it seems for some people to willfully resist what seems to me to be totally, unassailably true and rational. There's a lot of philosophy of a lot of different kinds that deals with these kinds of problems, many of which I've encountered simply by being a philosophy major and having to take certain classes: the ways that "discourses" can not only shape but determine our thought; the ways that truth claims can be justified, argued and defended; even arguments that go all the way to the scale of the brain and try to account for knowledge exists in our minds. There's also been a fair amount of media coverage about the ways that new media technologies can function not to widen our worlds, but to make them smaller (I think we may have even talked about Cass Sunstein's book about the internet in this class, where he argues that the internet works to actually reinforce our preselected biases, because we tend to engage with perspectives to which we are already drawn).

It would be really cool to spend even just a little bit of class time tonight or next week talking about the physical systems that make possible this kind of selection (which seems at least superficially related to what we are going to be talking about in our presentation). I also think it's cool, as a philosophy major, to see this really promising intersection between what I'm studying and what people in the natural sciences are studying; it doesn't really seem possible to understand these issues without taking pieces from several disciplines (which is, I guess, what this class is about).

LinKai's Pedagogy Reading:

Why not establish an "intimate" connection between knowledge considered basic to any school curriculum and knowledge that is the fruit of the lived experience of these students as individuals?

How beautiful this statement is.

How often do we find that the instructor actually gives credit to the students, acknowledging that they may know more about a topic than himself? Perhaps it causes a bit of anxiety - a bit of a power struggle. Well, hats off to those who welcome students' expertise no matter which area. We are all researchers, observers, participators in a variety of things that allow us to know a little more about such topics than others. Experiential learning is thus something to be highly valued and should be emphasized in the class room. Can you imagine asking the opinions of 5th graders on some recess or after-school activity? who is more likely to play this kind of game and why? etc... What budding anthropologists they would be...

Wow that is a really

Wow that is a really beautiful quote...people also tend to learn more by making personal connections - so when children can connect their own experiences to what they're learning and give any kind of input, it makes those connections stronger and helps them retain and know what they're learning (although the personal connections can get a little much in some classes...). Right now it seems like we have a divide of education in classrooms and values at home - maybe if we narrowed that gap kids would learn more and be "better" people...? After all, values definitely play a role in how children learn the information being taught to them (as we saw with the cognitive unconscious), why not bring more abstract ideas/values/morals etc. into classroom discussions at an early age?

to be wrong is kind of fantastic

how do we change our society from producing kids that are afraid to make mistakes.. afraid to bring the new idea to the table because they will be punished for it or labeled as ridiculous? somehow, we need to bring education to a level where children/students are accepted when they bring a different perspective to the table, even when it goes against the grain, especially if goes against the socially accepted "truth" ... being wrong produces more exploration than being right - pursuing this link may help in transforming a piece of education.

I'll a more thorough post

I'll do a more thorough post later, but before then I wanted to share this article that I found-

http://www.archimedes-lab.org/best_teacher.html

It's short, no worries :) Just an answer to what we can teach in school even if nothing is true.

Notes from Group Discussion

a. For group consideration: "if nothing is true, what are we teaching/should we teach our kids?"

i. Ask questions so that kids can accumulate knowledge to gain some sense of truth (or truth as they see it) knowing that it may change; apply inquisitory skills

ii. Gain a better self realization of own place in the world and emotional attachment

iii. Gain a comprehensive understanding of facts and general knowledge

iv. Train them to be critical thinkers

v. Function in society and understand social norms and know the origin of your beliefs and where they fall/are affected by society

1. Goal is to live a happy fulfilled life

vi. People want/need a version of truth for boundaries in a world where there is not truth

1. Time being linear vs. cyclical

2. Evren- no necessity for truth in a world where nothing is true; natural to have some sense of truth to satisfy a need for absolutes

3. Abbey- it’s intuitive to need truth because of the natural construct of the brain

a. Religion as an example

b. The Invention of Lying

vii. Wouldn’t change much about adolescent education

1. Cultural norms that children should be taught in order to function in the world; important of training them as critical thinkers; need for expansion of personal understanding of knowledge thru high school

a. Need to know how to write

2. In college, should be critical thinkers and are able to create their own truth and decide how to pursue truth for themselves

3. Constantly teach kids that there are different opinions about the same topic/idea; tolerance of other cultures, ideas, etc

Revisiting Fun

In group #4 we disagreed on two grounds. First we disagreed about the implication of the question "If there is no truth, what are we supposed to teach our children?" What is the truth that is implicated here? We tentatively settled on "absolute truth". Now, we arrived at the postmodern idea of truth: everything is constructed. Then the question becomes that is the construction of truth also a construction? The absolutism of the assertion of the "construction of the truth" begins to show.

What should we teach children when even the idea of the construction of the truth is deconstructed? It seems hard to find grounding for anything. I don't think we need to be a cynical absolutist and say that nothing about the world can be captured meaningfully, because nothing is permanent. It is false to conclude that there is no continuity. There is dynamic continuity precisely because things and ideas are constructed and deconstructed constantly. What is standing at this moment as the truth serves as the materials for a new cycle of change.

What are we supposed to teach children then? Just let them play games. Essentially, in the constructed world what we are doing is playing games: exploring boundaries, finding detachable parts and build them into a new entity. Are there rules for this game? Not rules exactly but certainly there are limitations. The limitations are at least: what you can find as detachable units, your creativity, your interest, and stimuli. We have not yet talked about social expectations and normative behaviors. To take a grotesque example, a child might be curious about the human body and its intricate functions. He then proceeds to dissect a pedestrian on the street. Most people will find this to be morally horrifying. The game is over. So even within an extremely liberal environment there are some seemingly inviolable norms for how to play the game of construction.

...

I like it! Can't say more but that I like the way you have defined and legitimized fun. I think you are on the right track in the way you are answering the question of what should we teach children. Essentially, some of the greatest scientists, theorists, writers, and experiementers have come across knowledge and understanding (despite the temporality of ideas that are bound to be refuted or reconceptualized) through having playing games and, as some would argue, having fun.

NOTES from group 3

Naa Kwarley, Simone, Lars, and Bennett!

Naa Kwarley and Simone believe that there are truths! Universal forces that manifest, in different ways, cross culturally, e.g. love, justice, and faith.

Bennett wants to teach kids love --> then everyone will love everyone else, and learn to love the things that love them.

Lars had the idea of an "asterisk" approach to education; teaching things as truth, yet also making it known that the concepts are not always considered to be true.

consensus:

that we do need to teach something as true, however contextualizing our teaching is important. teach kids to challenge what is taught, and to think critically!

trauma

what we spoke about in class today about the manner in which the brain handles trauma made a lot of sense to me, but it also left me with a lot of questions.

the concept behind trauma is that the story teller cannot handle some information and so it leaves it out, and you end up behaving/acting in a certain way without always being conscious of it.

but, what then are flasbacks? are they attempts by the story teller to find a story for what happened? where do panic attacks, anxiety attacks and bouts of depression (that are due to events that happened in your past) come from?

i guess i don't really understand how it's possible for there not to be a place in brain where things are suppressed...

thoughts?

vision

So I think I'm the one who has to take responsibility for the introduction of the insipidly mission-statementy phrase "boldness and vision" into our class bank of generally desirable things (worse still, I think the phrase came flying off my finger tips because it was in the air during the College's "Bold Vision for Women" 125th anniversary). But I'm happy to report that I think I'm beginning to see the fuzzy outlines of its possibility.

"Local truths." Something clicked there for me tonight. Freeing ourselves of assumptions about there being a Truth really does mean escaping a kind of tyranny, escaping from a scenario in which we're always bound to fail, because we're aiming at acheiving the impossible. Well, not that we don't stop failing to achieve Truth, but we can "Try again. Fail again. Fail better" (Beckett). Failing better, I'd say, we can equate with local truth. And you can call it better failure if you're in that kind of mood, or you can call it finite success... or something. This means understanding ourselves as limited individuals with limited knowledge. We're not "failures" because we're limited. The limitation is the one thing that can't be otherwise. And it's actually where the opportunity for "vision" comes from. You can't see beyond the vanishing point of the horizon. Okay. You can see as far as you can see. And you can conceive of a plan for traversing that space, a plan that you can actually feel relatively confident about. Not so if you're trying to project yourself around the globe in one go. And this needn't feel like resigning oneself to some lesser satisfaction... because the horizon moves forward when we move forward. We can't have access to the vista afforded some imagined, omniscient outsider. But every possible ground level angle of appraisal, every real person sized chunk of surveyable landscape is still potentially available to us. Just not all at once. Still looking for boldness... but maybe boldness ought to be replaced by simple curiosity, the curiosity that encourages you to creep forward, allowing your horizon to, bit by bit, expand, and expand, and expand.

notes from our group - group 4

the question posed was 'if there is no truth, what are we supposed to teach our children?'

though our group did not come to a conclusion or compromise, we came up with a lot of ideas. some of them are as follows:

- we can still teach knowledge. knowledge being the skill to see that things are constructed.

problem with this - if we begin to teach kids that everything is constructed and there is no truth from the time they are in kindergarten, it will take us a few weeks. because if they don't have enough knowledge built up in them, they have nothing to break down. also - isn't insisting that everything is constructed a forced truth in itself?

- truth has many definitions. there isn't one way to get to the root of this problem. besides, in school, we are taught to understand. we need to understand A to get to B, but that doesn't mean that either A or B is true.

- maybe we should just teach children as we teach them now, teach them about science, art, religion, literature. but don't enforce a single concept of right and wrong on them - give them the material and let them ask the questions and find their own answers.

- by saying the world is constructed are we saying are we saying it's all random? that there are no patterns? maybe truth is recognising the patterns that exist.

problem with this - the patterns are always changing - if there is no continuity, how can that be the truth?

- the kids should just play games =)

What to teach if anything

When I think of teaching, I think of something that is both controlled and uncontrolled, conscience and unconscious...Teaching does not only occur within the confines of a classroom. We are constantly teaching our children through our behaviors, lifestyle, ect. So in thinking of teaching as something that occurs inevitably, I think that the question posed in class was pertinent....Given that there are no absolute truths, we should teach our children how to think(not what to think)- make sense and be critical of what they see and hear. We should teach them how to create and encourage individuality(to a certain degree) and confidence, but at the same time promote team-work. We should definitely teach our children love as bennett stated.

Post new comment