Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Brain, Education, and Inquiry - Fall, 2010: Session 7

Session 7

Braiding three lines of inquiry

- our own experiences of education in relation to other peoples'

- doing our own experiment in co-constructive inquiry

- exploring usefulness of insights from studies of brain for thinking about education

Issues of own experiences in re other peoples' (from first web papers)

- importance of encouraging "creativity" in classroom (vs rote learning) - Abby Em, Amenah, Angela Digioia, bennett, evren, FinnWing, jessicacarizzo, kgould, kwarlizzie, LinKai Jiang, skindeep

- importance of achievement gap, standardized testing, acculturation - D2B, eledford, epeck, L Cubed, Liz J, ln0691, mmc, simonec

Exploring a contrast/difference:

"Once the achievement gap is closed, I welcome any and all criticisms of our system’s nuances, how we handle ingenuity, or the way classroom discussions are held. The first step is getting everyone in schools and graduating with the proficiency to exist competitively with one another in the “real” world." ... simonec

"As soon as we get into the language of utility we are talking about survival, and even if we grant that there are multiple ways to survive, we still think of survival as a contest in which the fittest win, so we think of ourselves as progressing ... the whole apparatus leads nowhere, produces nothing ... Creativity is a matter of reordering or restaging this circular movement. There is no accretion, only a more and more finely attuned consciousness of one’s own ultimate inutility" ... jessicarizzo

"There is no such thing as a neutral education process. Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate the integration of generations into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the ‘practice of freedom’, the means by which men and women deal critically with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world."... Richard Shaull, from an introduction to Paolo Friere's Pedagogy of the Oppressed (skindeep)

Reframing the achievement gap and From the achievement gap to the education debt

Can we find new stories about the objective of education, individual and/or shared? (Enuma, Emily, Abby, Maheen, LinKai; Elana, Christina, Angela, Bennett, Devanshi; Liz, Ellen, Evren, Kate, Naa Kwarley; Mae, Simone, Jessica, Lars)

Class is itself an experiment in a particular form of education: co-constructive inquiry

Learning by interacting, sharing observations and understandings to create, individually and collectively, new understandings and new questions that motivate new observations

Depends on co-constructive dialogue, being comfortable sharing existing understandings, both conscious and unconscious, in order to use them to construct new ones. Need diversity of understandings, need to be able to both speak and listen without fear of judgment. Need to see both self and others as always in process, always evolving

"I believe that regardless of what your job is, sometimes doing less is more effective, and I think with teaching that is definitely true. This belief was fortified last night when prof. grobstein made the comparison between a classroom and a flock of migrating geese and how in both cases there is no leader, but instead a group dynamic that decides the direction of the group." ... Evren

"I think that the students are inevitably the ones in control because they grant the teacher positions of power and ultimately decide their own roles as students, but does that necessarily imply that the teacher is not a leader and that there is in fact no leader? Does a leader have to control?...How do we define leadership?" ... L Cubed

Sign up to try facilitating co-constructive inquiry yourself, individually or in small groups. Email me with names/topic/date preferred. Something on how something about brain does (or doesn't) help think about education. Paper on this topic due 1 November.

Continuing from where we are: from last weeks forum and the previous

I feel like if we have so many "selves" then we would have no consistent personality and instead our actions would be all over the place ... ln0691

This article actually describes my experience of reality pretty well ... it seems right to say that we are each more a plurality than a central authority ... the "selves" are intimately connected, set up to help each other out, balance one another, or sometimes in a sort of self-sabotaging structure, but always in a more complicated relationship than just competing ... jessicarizzo

I see us as having situational roles/identities more so than selves, as selves don’t represent who we truly “are.” .... mmc

I think that my different simones are my own creation, as the stage, home, and classroom simone are conscious creations that i have established in order to try to be as successful as possible in diffrerent situations ... simonec

I very much like the idea of there being multiple selves and not having to choose one of them to be “me”. However, like other similar post-modernist ideas, it sounds great in theory but might not be applicable practically ... Assuming that some of these parts will be in conflict with each other, how do you live your life? How do make decisions? Maybe that’s why multiple personality is considered a disorder. This can also be generalized for multiple selves to multiple realities/worlds. How do we feel about that? Do we see some inherent truth in it but disregard it because in the world and society we’ve constructed, it just wouldn’t work? Moreover, what implications does that have for education? If we let go of the idea of there being one self, then what does education do? ... Amenah

Is education the medium by which we establish and develop our "selves"? ... L Cubed

Thinking of the essence of a person in terms of their nervous system is an idea I would like to pursue more ... epeck

Can we choose the extent of how aware we are of something? Or are we always aware ... even when we think we're not? ... eledford

The idea of the biparte brain provides the biological explanation of why we cannot know the world “directly”. Our most immediate contact with the world is processed through the brain stem, or the “frog brain”. The experiential data generated is sent to the cerebral cortex. It is in this upper region of the brain that we experience the world ... Some philosophers like Hegel redefines our intellectual quest and say: we can’t know the world as it is, however a wealth of the world is available to us as mediated, through our consciousness. Perhaps this is where we can start most fruitfully ... LinKai Jiang

I got excited last class when Paul demonstrated the ability of the brain to synthesize contradictory input by having us focus on on object with only one eye, then watch it shift when we used the other eye... it's a phenomenon/effect called parallax that gets taken up as an extended metaphor by Slavoj Žižek in his book, The Parallax View ... Attempts to master or get the whole/correct picture will always prove futile. What we want now is agility. This is where Žižek says truth is, not in one philosophical system or the other, not in the image produced by the input coming from one eye or another, but in the movement between the two ... Truth isn't a representable image but that which cannot be contained in consciousness. Because it can't be contained. It's always moving. It's just that jump back and forth, or from one thing to the next ... jessicarizzo

The above idea is very liberating. I was thinking about it today. If everything that we feel is from our neocortex, with help from the "frog brain," then we should be able to have a great deal of self-control ... FinnWing

Why does having all "thought" in the neocortex suggest that we can control our thoughts? Maybe because our thoughts are sort of not directly responding to stimulus, but have space (in the interneurons?) to process whatever input or output our nervous system deals with? There's that self-help adage saying that the only thing we have control of is how we react to a situation - we cannot control the input, but the output is within our grasp and we are able to change the way we think about and react to situations. Is this true? ... epeck

his reminds me of this game that we played in high school. The game is simple, the object of the game is not to think of the game. When you do think of the game, you lose the game and when you dont think about the game you win the game. Those are the only rules. In this sense, the only way to win the game is not to be aware of it. Once you are thinking about the game, however, it is pretty impossible to forget about it ... At the same time, there are often points in time where thoughts simply pop into my head. I didnt try to put them there and they are not generally connected to anything I am doing at the moment. This could connect with the fact that the nervous system is a generative system. Instead of completely controlling our thoughts, our nervous system is working with input/output as well as input from within the nervous system ... ln0691

you fall off a swing when you're really young (say five years old), and the swing hits you in the face, requiring you to go to the hospital. fifteen years from then, you have no recollection of that at all, but you're not very fond of swings. sometimes you have bad sleep but you don't relate it to anything because well, everyone has bad sleep sometimes. until, one day, you remember. now, as a five year old, the experience scared you, and so you stopped thinking about it. the stoppage of thought became a habit and you completely erased it from your memory. or so you thought ... skindeep

I could be persuaded to believe that any individual has different characteristics and decision-making selves that arise depending on the situation. However, it seems that this is a one-way street. An individual is able to say that they should be excused for their bad behavior because they were not themselves (whomever that is) whereas they would judge and critique someone else with whom they associate a negative experience, say getting reprimanded at work or at home as a child (even if it’s only one time), as a mean or bad person on the whole. Now, that doesn’t seem fair, does it? Where does moral judgment arise in the brain and how do we decide which of our “selves” wins in the end? ... Angela DiGioia

Implications for education (to date):

- Brain as loop, active empirical inquirer, can create new thing

- Perception, action, knowledge as construction

- Stop presenting understandings as "right," "definitive"; present instead as foundation for developing new understandings?

- Diversity in classrooms an asset rather than a problem?

- Ability to see things in multiple ways a virtue, a desired result of education?

- Inquiry skill is present at birth, rather than dependent on maturation/education

- Acknowledge, make use of distributed/bipartite organization, internal "conflict"?

- "boldness/vision," "choosing ... questions [one] wants to ask, or articulating those questions [oneself]" is related to thought/feeling and neocortex, reflective versus unconscious process

- ????

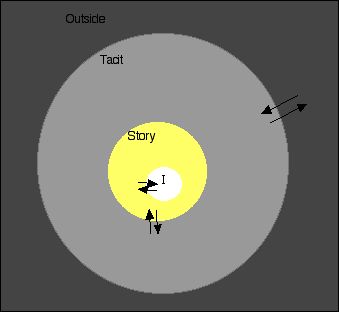

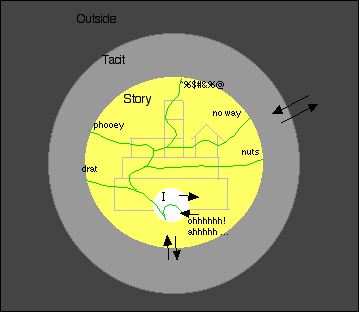

We are distributed systems, constantly using conflicts to generate new understandings

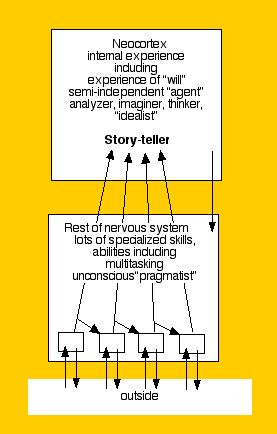

The bipartite brain - adding in the neocortex (where is Christopher Reeves?)

More on bipartite brain

Blindsight, cortical paralysis, dissociative fugue, skilled athletic performance

Dreaming, sleep walking, locked in syndrome

Relevant for thinking about constructedness of world but also of self: pain, phantom limb pain, confabulation

Interactions of cognitive unconscious (Marvin Minsky, Society of Mind) and story teller

Thoughts, feelings, aspirations not parallel to cognitive unconscious but rather derived from it

Emotion, intuition not distinct from thought but a part of it (Antonio Damasio, Descartes' Error)

Internal co-constructive dialogue/inquiry as well as external

Internal conflicts (weight control), added capabilities: to conceive beyond experience

Constructing a story of the world

- informed guessing and beyond

- some more examples

- and beyond

- creating meaning

- Implications for understanding "understanding"?

Constructing a story of the self and of one's relation to the world

|

|

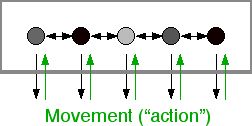

Loop 1 Empirical knowledge generated by conflicts with outside world

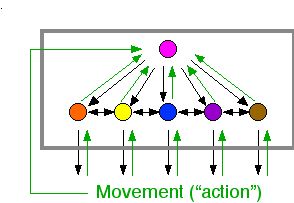

Loop 2 New understandings generated by internal conflicts

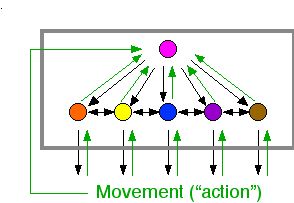

Loop 3 ..... morality, interpersonal relations, culture to come

Have a look at

- Culture as disability

- The emotional dog and it rational tail (click on title for .pdf after entering info)

- The moral life of babies

Your continuing thoughts about all this and its relation to the classroom in the forum below ....

Comments

Money, teachers, and feelings... oh my!

The debate about money, teachers, and education is ongoing. The question here seems to be, is giving teachers more money as an incentive to teach well or even teach in the first place a reasonable thing? Some seem to think that just in asking the question itself is enough to say no, it is not reasonable because money doesn’t make good teachers and if teachers don’t want to teach with the salary they have know, then they don’t want to be teachers. This argument is tricky, because in one way, yes, we hope that people who want to be teachers will do so without worrying about making money. The thing about that is the fact that we live in a capitalist society and money is a motivator. Money won’t fix everything but why can’t we start in investing more into education then say, the military and a losing war. U.S. policy and decision-making should try to focus/work on domestic issues instead of trying to fix what they deem as “problematic” in the other parts of the world.

As discussed, money doesn’t make good teachers. But then what does make good teachers? Are good teachers those that are aware of their student’s feelings? By trying to understand student’s feelings, would teachers then know how to reach their students better? And if this is important, would it be required for teachers to be extroverted people?

Learning for Learning's sake

In the moral life of babies article the author points out a possible role for the early moral of the babies. He writes,

"an empty head learns nothing: a system that is capable of rapidly absorbing information needs to have some prewired understanding of what to pay attention to and what generalizations to make. Babies might start off smart, then, because it enables them to get smarter." Leaving the social goals of learning aside, learning enables one to more even more and faster. This could have both a positive and a negative implication. On the one hand this sounds exciting that this understanding of human intelligence points to an effective way for increasing people's learning ability. Through accumulation of knowledge and understanding, the brain finds short cuts and forms increasingly better intuition of the world. One the other hand, it seems easy for one to develop ingrained biases. The previous biases will only facilitate faster learning of other biases by selecting a preconditioned cognitive path. Psychologist Henrich and his colleagues concluded that "much of the morality that humans possess is a consequence of the culture in which they are raised, not their innate capacities." The author points out that we do have some sense of right or wrong. This is not incompatible with Henrich's idea that morality is enculturated. It could be that the ability is innate but this ability is so general that the culture comes to determine the exact views and values of one's morality.

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/09/magazine/09babies-t.html?pagewanted=3&_r=1

Some thoughts, first, on

Some thoughts, first, on examples of collectivist versus leadership models in education...our conversation last week reminded me of an exercise we did about once a month during one of my classes senior year of high school. We would have Harkness discussions, a model of classroom conversation that began at some Ivy league university according to my teacher, I think it was Harvard. Basically, the teacher removed himself from the discussion, and it was the students responsibility, given a topic of discussion (we usually did the book we were reading for class) to engage themselves and each other in a conversation about it that was enlightening and the product of the group as a whole with no acting leader. Honestly, I never liked the Harkness conversations. We'd end up searching around for something, anything to talk about, not really knowing where to focus. It was sustained BS for the most part: we wanted to participate, of course, and to have a say in the course of our learning, but dissolving leadership to that extent didn't lead us to coming to a direction together, it left us going nowhere. What we looked at in class is the incredible effect of group intertia, but it goes in both ways. A group at rest will also stay at rest.

I had a similar experience this last semester when group presentations were the bulk of our learning of Joyce's Ulysses. There's simply only so much you're going to be able to "discover for yourself" without someone imparting a foundation and then leading you in potentially fruitful directions. It was really difficult material, and we didn't have thorough enough understanding to benefit from teaching and being taught by each other about it. We were, again, just desperately looking to have some kind of conversation, but we didn't have the raw knowledge about the book for our conversation to lead anywhere. Structure prevents aimlessness, even if it has to be to an extent at the cost of perscribing particular aims that, yes, limit you some.

I do agree with you that

I do agree with you that guided learning is more productive. Having someone lay down the foundations and lay out the general map of the inquiry is very helpful. the Moral Life of the Babies article the author talks about the idea of being smart enables you to be smarter. That is, if stand on the shoulder of an intellectual giant you're going to see further. But I think there is something valuable to be said about the virtue of working out a problem on your own. Is Aristotle stupid (most of his physics are proven wrong)? Most people if not all will say no. He developed his intellectual capacity to a great extent, despite the fact that he didn't have the resource of evidences that we have. He was a genius in his own time. I don't want to say that personal intellectual ability should trump knowledge in all instances. But I do want to bring attention to the virtue of intellectual independence: working it out on your own.

Some things we didn't discuss

Some things we didn't discuss in class but that I think could really impact the education system:

(some of my friends saw Waiting for Superman, and we were discussing these ideas...)

-tracking - Should we be tracking children, and separating them from one another based on ability? Or, should we keep all children in one class and deal with their differences within the one classroom - would this help bring our standards up by holding everyone to a high standard? This might be an area where putting money into a system could help - we could have more teachers in each classroom in order to facilitate the range of ability and methods of learning that would be in untracked (?) classrooms.

-tenure - Why do teachers get tenure so easily? In my school district, teachers simply had to teach for 3 years (give or take a year) in order to get tenure. This seems too easy - in other professions, one constantly has to prove their skills and expects to be punished for lacking abilities. Do other professions have such extreme job security? What is the function of tenure in providing quality education to all students?

Could changing these things change our education system?

In our class discussion, the

In our class discussion, the topic of paying teachers more was brought up.

I think I would like to take a slightly different position on the issue. Um, I would be the first to say that of course teachers are not paid enough, but as far as I can tell, they are paid a living wage (sure, it won't be enough to buy a mansion or pay for your child to go to private school, or Harvard)..... but I don't think money is instrumental in making great teachers, or in any profession for that matter. Yes, there are many brilliant people who venture into law and medicine because of just how much money there is to be made, and see where that has gotten us: lawyers who care nothing for justice and doctors who don't know the first thing about nedside manner and treating patients well.

I think that the most important thing about teaching/making a good teacher/inspiring more people to become teachers (even though money is also very important) is pride in the job, and pride in the job well done. It makes all the difference - in the teacher and the children. And I am positively convinced that seeing people who are proud of what they do, and who pour themselves wholeheartedly into developing their students' minds will make more of a difference in the children being taught and inspire more people - the right kind of people - to become teachers than anything. It will also improve the quality of teaching at many schools - more than increasing the salaries would.

musings

a few days ago, a friend of mine came back from a high school in inner philadelphia where she was volunteering with a second grade class. when she got back, we sat and spoke for a while about her experiences in the school and what the kids were like. it was at this point that she brought up something crucial - the school she was in, was known to be a 'difficult' school, with 'problem' kids. and yet, the school in itself, with its infrastructure, reminded us both of the schools we attended, in India. - they weren't in the best condition, we didnt have computers much less a computer lab, the teachers were underpaid and the facilities weren't great. yet. our schools were considered one of the best in our cities. and so, we were treated with respect, and intelligence, and people spoke to us like they expected things from us - as a result of which, we learned to work and rise up to those expectations. and i cant help but wonder, how much of the problem we face right now, has to do with this - stereotypes, labels and expectations. if you dont think a child can do something, and everyone around him believes he's bound to fail, one day, he'll learn to believe it too. and whats the point in that?

epeck's point....

... I had not really thought about it either!

In all of our time in class discussions, I feel that we have not brought up the idea of less time in-school as an option. For all of our radicalism, it seems that we have been so well socialized that even when we talk about education reform it is hard for us to leave the realm of its current manifestation, a five-day-a-week, 8-3ish, structure.

I have no idea what another format would look like, however I do believe that once students are old enough that school is no longer serving as a kind of child-care, that perhaps more on-site learning could be an interesting approach.

Notes from Group Discussion: What is the object of education?

Group members: Abby, Angela, Bennett, Elana

E: The object is to make children feel like people; respect them, listen to them, treat them like people that are knowledgeable.

AD: Teachers should be facilitators; education should be engaging

Abby: Differences between Montessori and Traditional Education; differences in responsibility and structure

Bennett: Do you remember things from grade school? What are they? Why do you think that you remember them?

Overall objective: students are respected and, after years later, are able to apply the skills to the current situation. Students have a certain consciousness in the real world; they seek out what is new and unknown to them to expand their knowledge.

Emily, Maheen, LinKai, Enuma Group Notes

Topics within our discussion:

-commentary on exporting science & math studies and professions to Asian & Southeast Asian countries

-goals of society vs. personal goals

-culture plays a great role in education and academic discipline

-creativity or discipline needs to be instilled from the start

-rigor vs. intellectual creativity, humanities vs. sciences, creativity vs. rigor

-creativity in sciences -- theories and resynthesizing

-who judges creativity if it is defined as a diversion from a basis line?

Group statement about the current objective of education:

Creativity, discipline and utility are not contradictory; they are compatible. There is a basis/ a foundation and then comes the intellectual creativity.

Group Brainstorm: Liz, Ellen, Naa Kwarley, Evren

The objective of education is to foster creativity and innovation, but the practice often falls short of these goals. Education has a purpose regardless of its form, even "education for the sake of education." When a person is being educated in a certain area, he/she learns much more than the skills that are being focused on. For example, in an English class, a student may be learning how to extract information and ideas from reading texts, but by writing essays he/she also learns how to think critically and analytically, form arguments, and present those arguments.

It's interesting that school is often meant to prepare students for the real world, by a school's society is often in it's own bubble and separate from the real world.

In some ways the process of education has become prolonged (college, followed by graduate school, followed by professional school, etc.) instead of producing younger educated people to participate in society.

While the goal of education is to create innovators, many of the most prominent innovators are college dropouts, such as Steve Jobs and Bill Gates.

Conclusion: Even if we don't know it at the moment, we can retrospectively realize the purpose of our education.

I haven't really thought

I haven't really thought about the point made here about education ideally getting students ready for the "real world" or the rest of their lives. I definitely think of education as preparation, and hopefully as teaching skills that will be needed after formal education has finished, but somehow I never questioned the time spent in school. I know that Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are the typical examples of influential people who dropped out of college, but if all people of a certain degree of influentiality (?) were studied, I wonder if there would be more college dropouts, or people with high levels of formal education. I'm not sure, but I suspect that Steve Jobs and Bill Gates are exceptions. Then again, this could be because as a society we value higher education so much that those who dropout are looked down upon and therefore will find it very difficult to gain power in society.

Should we be spending less time in school and more in the real world, or maybe more of school should be dealing with real-world experiences, like praxis or lab courses? I wonder how learning things through experience in the actual field vs. in the classroom would change our level of comfort and skill in those areas.

Teach-ing prestige with a pretty penny?

I have been grappling with our class discussion and group commentary on what can make or bring good teachers to the educating profession. After our class, I encountered several formal and informal meetings that coincidentally went into the topic of teaching, teacher recruitment, TFA and teacher incentives/tenures. It amazes me that within all but one conversation, all groups and individuals believed that putting more money in the pockets of teachers (or in the least, incentivizing them) would improve teacher-to-student reception, and student learning capacity and teacher-effectiveness would increase. While I agree that teachers within the system need motivation as much as students do, I cannot stand behind the notion that paying them more or incentivizing their jobs will generate a motivation in line with improving effectiveness and quality.

The profession does, as we said in class, need to be destigmatized. There are negative connotations attached to the pursuit of teaching that push many potentially gifted individuals away from the profession. However I do not believe simply increasing the salaries of teachers will relay the right message to pursuers or even truly destigmatize the profession.

Furthermore, we must also take into account the effects raising teacher salaries will have on students, especially within inner-city schools. I was reading an excerpt from Jean Anyon's book Ghetto Schooling: A Political Economy of Urban Education Reform, and within a 10-year old student states, "Most teachers here don't teach us...because of the kids. They run the halls and makes the teachers upset...they think [teachers] just doin the job for money, they don't care" (Anyon 32). Personally, I wish this was the first time I've heard a statement like this but it is not. I have heard countless judgments of teachers from students who believe teachers are just in the classroom for their paychecks, paychecks that are not affected by student failure or success. If many students already believe that money is what brings their teachers to the classroom and rebel/are academically disturbed and unethusiastic because of that belief, the imagine what message will be further engrained or newly engrained.

I am sure that something is working here also, psychologically, though I will probably fail to explain it technically so I'd like to save that discussion for my in-class facilitation (if anyone is interested in teaming up with me, that would be great!) Nonetheless, I would love for us to look at all the links and chains attached to teacher quality outside of the teacher.

Motivation

It seems that the idea of motivation is really important in the context of education. Teachers/educators/administrators are all motivated to get into the field of education for various reasons (money included). Differing motivations can lead to a variety of outcomes in the classroom, but not all of the success of the classroom can be placed in the hands of the teachers and educators in schools. Every single student enters the classroom with different motivations and these motivations change constantly. I remember a while back some DC public schools started a program where students were paid for getting As. I think this program shifted the idea of motivation in the classroom completely. Success in the classroom is now tied to immediate monetary rewards rather than the possibility of monetary stability in the future job market. If both teachers and students are only motivated in the classroom because of money, I think it will shift the goal of education completely.

It would also be interesting to see how such programs would affect the process of judging a teacher's abilities. It might not be that a teacher is incredibly interesting, their students may simply be getting better grades because they are now monetarily motivated to do well in class their overall perception of/motivations in education shift as well.

I think all of what you

I think all of what you write here is seriously real and true, and makes what I said in class seem far too simple. I think you're right to point out that a quality education is not reducible to money: there's no direct relationship between how much money a teacher makes and how good of a teacher he or she is, and it's completely possible to have a wonderful school experience in an underfunded school district, or with an underpaid teacher. The only point that I was trying to make, which I still think is true but probably not nearly as important as I was making it out to be, is that it seems like we ("the public," or the news media, or etc.) concentrate time and energy and attention on where our tax money is being spent. If we allocate substantially more money (way, way more money) on our education, I think that there's a chance we might begin to take education really seriously as a value, as something worth making high quality and accessible.

It's pretty transparently cynical of me, and maybe lazy too, to appeal immediately to our baser instincts – ideally, it be nice if people just "cared about the things that matter," rather than having to have some kind of material incentive. But I also think there's a good chance here to use some of the things that I've learned about the brain to make a less cynical, less reductive claim. It's probably not true that people simply always do things for money, or that money is somehow inherently worth doing, and our brains are hard-wired to stay focused always on making money. The brain, as we've learned, is a system that flexibly and adaptably handles inputs and outputs. It seems reasonable to imagine that there is or could be a way to reconfigure the relationship between conceptual inputs and outputs – we're not stuck with a system that demands that money have a high value. So then the question is how exactly to affect those changes, which is something I think we could explore in class, if we want to.

Just Another Story

Last class we established that the neocortex is essentially a story-teller. It takes information from all the different parts (that communicate with each other and the outside world) to create a single, coherent story. So everything we know, everything we have ever known is a construction. There are no truths and nothing is for sure. Philosophers such as Descartes, have been playing with this idea since the 1600s. He believed that everything should be doubted and that everything (including what we perceive from the senses) is unreliable. There is a also plethora of psychological studies about the unreliability of perception and memory. E. Loftus, for example, demonstrated how easy eye witness accounts are to manipulate by the way questions are asked and supplying subsequent information. Zandy and Gerard also did a study on how personality and different life histories perceive the same thing in starkly different ways. Biology tells us the same thing. But where does that leave us? We can take either end of the spectrum - either there are an infinite number of truths/realties/equally valid constructions or there an no truths at all - but both are equally problematic. If there are no truths then there is no right or wrong and society falls apart. If all constructions are valid, then which ones do we adopt because surely we apply all of them to society (some, for example, might contradict each other but that doesn't make them any less valid). Sure, we can have a shared construction, but then who decides which construction is right and the best one to follow? The majority? The bourgeoisie? The past/the way things have always been? Moreover, if nothing is true, what are we teaching/should we teach our kids?

Confabulation = Construction of Construction of...

We didn't really discuss confabulation in class in great detail, so I tried to look into it more. When I researched the definition of confabulation, many theories came up often revealing it to be an extreme disorder of mixing true memories with fabrications; however, confabulation probably happens all the time to us. By this I mean that are memories are formed by an experience, yet also by other past experiences that had previously shaped our thinking or perceptions. When you recall a memory of a certain occasion as if it were yesterday, and your sibling recalls it with very different details, neither of you are wrong - they are both memories (just probably confabulated) and it shows that there are multiple truths. In the field of anthropology, life stories and memories have been called into question as to whether they are reliable and truthful resources, yet we can simply look at them as "constructed understandings of a constructed person's constructed point of view"... experiences and memories are not linear but something we repeatedly mull over and allow to evolve. So does this count as confabulation? Am I on the right track?

Dreams

Yes... I think when we hear confabulation spoken of in a clinical psychology/psychiatry context we're usually hearing it being described as a kind of pathological phenomenon. What you're suggesting is that it's not only not wrong or diseased, it's actually the more accurate (less wrong) model for understanding the way our brains are always in the process of creating and revising what we know about our pasts, that undifferentiated experience-matter from which we construct an identity. I think this is super interesting to keep thinking about for it's own sake, but also because figuring out how to be in relationship to our past selves has got to tell us something useful about how to be in relationship to our future selves.

In Freud's early thinking, he theorized the appearance of neuroses caused by early childhood events/traumas like witnessing the "primal scene" or being, as a young girl, seduced by the father or other older male relative. Later, he revised this thinking, positing that these traumas needn't have occured in actuality for his theory to work just fine, for the neurosis to be explainable according to the model he'd laid out. The patient might have merely fantasized the disturbing scene or seduction (for the record, the latter hypothesis has been thoroughly shredded by feminist critics). But I think the point to take from Freud is that it's really all about the narrative you create. If you "remember" something and believe it happened, if it colors your interactions with people, shapes your understanding of yourself... well, then how can we say it's less real than the event that "really" happened? The analyst has to take it into account, and the patient has to work through it in the same way she would work through any other memory of an experience.

I think about this in relationship to dreams sometimes. Not that we often have a hard time telling the difference between dreaming and wakefulness... once we're awake. But have you ever dreamt about a person you know, maybe even someone you're quite close to, and felt your wakeful (conscious) relationship to be irrevocably changed based on the events of the dream? This may sound melodramatic.. or just kind of strange.. but in at least a one-sided way, the relationship (built out of past experiences) is different... because the dream (unconscious) experience goes into the bank of stuff you've consciously shared/experienced with this person. You wouldn't hold someone accountable for something they said or did in your dream, but even if you're not going to let yourself interpret it as some kind of sign, you might not be able to help looking at that person kind of funny, or having a slightly different attitude towards them, which sets different conscious experiences in motion. Then it becomes harder to separate the conscious and unconscious.

Freud would say I'm having this dream in which this person says or does this thing because I'm repressing feelings about the person that I can't deal with consciously, so they show up in the unconscious... I wonder if what we've learned about the brain would actually encourage us to depriviledge the conscious even more and focus on what the infinitely fecud unconscious is telling us. Not just as a receptacle for "unacceptable" conscious impulses, but rather a free, id-governed (or ungoverened) space, id sans the negative moral connotation. Closer to Jung's description of the unconscious?

i found this really

i found this really interesting. the idea that something doesnt need to happen to you for you to be a certain way - just thinking, or rather believing, it happened is enough. this then adds to the idea of 'degrees of serious' - whether loosing a dog is as serious as loosing a family member - a lot of people would normally scoff at that and wonder how the two could ever even be compared on the same scale. but really, who decides? to someone, loosing a dog may be as if not more serious than loosing someone in their family - and honestly, can we really judge that?

moving on, i wonder how we distinguish between what counts as confabulation and what doesnt. when it comes to matters in faith, or matters of consciousness, who apart from the person who has experienced the situation can fairly decide if it actually happened or not? this makes me wonder about people with schitzophrenia, or people who claim they have seen god.

it also makes me wonder where then, is it okay to draw the line? because to be functional in this society, people need to be at a certain consensus about what did and did not happen, and what qualifies as an experience, and what does not. how else would we build concepts like morality, law, even education?

I'm Confabbed...

Is confabulation a construct of memory or vice versa? It seems like even someone's memory is confabulated since it is a "'constructed understandings of a constructed person's constructed point of view'... experiences and memories are not linear but something we repeatedly mull over and allow to evolve." I am comfortable with the fact that our memories are a construct of our interpretations of experiences and inputs that we constantly experience and that there is not absolute truth, but it seems to me that confabulation is a more technical term for the interactions between our imaginations and memories that did not necessarily happen in reality. Does that seem to make sense?

to add on...

To add onto eledford's idea of confabulation...

At least before this class, my general understanding of the idea was pretty extreme - that everything is physical, except for our explanations. For example, our arm may reach towards a glass of water for a physical and chemical reason, but we rationalize that we reached towards the glass because we were thirsty, when in fact we reached without even thinking about being thirsty. It's sort of like the idea that you don't think "arm - move." It just happens, and later is explained. This makes sens with the example of the hypnotized man walking "around the table" - he rationalized his experience just as we would rationalize and explain our behaviors, the only difference being that an outside spectator (the hypnotist) knew that the man's explanation was probably not the true cause of his actions.

Basically, our body acts and we explain its actions after the fact (and attribute our explanation to be the true cause of action).

I'm not sure if this is too extreme/if this is the way we'll be approaching confabulation...it's definitely an unusual way to think about the causality/control we have relating to our actions.

questions

this confuses me a little, by saying 'our body acts and we later explain these actions', do you mean that our body acts independently of our minds? what tells our body to act then? is it just our neurons? if so then do our neurons decide when we sit/stand/lean? and if they do, what part of them decides this?

i apologise for bombarding you with questions to which i dont know the answers. i guess these are just musings?

Small Groups, Education, and the Brain

Breaking off into small groups this evening was excellent. There is a lot to say and hear in class, and being in a small group enabled me to say and hear more depth of perspective, which I really appreciated.

Speaking about education, I think that students can do a lot to improve a class dynamic, this requires neither money nor smaller classes (although both could help). One way for students to improve a classroom is to work hard and be engaged, a lot of emphasis is placed on changing how we teach students, and some emphasis should certainly be on students to work hard, stay up to date on work, and be engaged. When this happens, I think that classes often feel smaller and more intimate; why this is is not immediately obvious to me.

For creating better teachers, I think that some more respect for the profession and some more money could help, although I think that money has diminishing returns on quality of product at a certain point (e.g. financial markets).

The brain has a role in education, patterns of activity make up thought, and patterns of activity are feelings. By disrupting patterns of activity it is possible to calm down a very frustrated or angry person, one way to disrupt these feelings is to make the person feeling them aware of them. Taking the example of a fourth grader who has parents who are fighting at home, this child is most likely frustrated and may act out (or not act out and just be very sad). A good teacher can often find a way to get through to this child so that she feels better; an understanding of the brain should allow this teacher to see that it is possible to influence patterns of activity for the child and then change how she feels, to make her less frustrated or happier. If we consider the child's pattern of activity to be only a pattern of activity then clearly changing that pattern of activity in a positive way can help break a cycle of negative feelings that the child has.

Money=Effective Teachers is a false statement

There were so many different thoughts roaming through my head during our last class....In my opinion, money is too often falsely assumed to be the cause of our failing education system. People think that if you simply pump more money into the system then all of the problems and inequalities of education will be solved. Truth is, regardless of the amount of money our system has, the fact of the matter is that we have ineffective teachers and as a result unmotivated and failing students. Hence, what we should be focusing on is getting effective teachers. I do not think that raising teachers' salaries would be beneficial or effective overall for the reasons that FinnWing stated. But in addition to his statement, I honestly think that if money is the source of deterrence from the teaching profession for potential teachers, then it is not the profession for them period. This may be a bold statement, but it is my honest opinion. Teaching is not about you(the teacher), its about the students. Its about providing them with the tools needed to be successful learners and advocates within their communities. Its about selflessness, compassion, humility, support, dedication.... This brings me to a side note on the question of what it means to be an effective teacher...

There is a book that was recently published called, "Teach Like A Champion" by Doug Lemov. I have not read the book in its entirety mainly because I think that it serves of more of a reference guide and takes on different meaning based on your daily experience in the classroom, but I think that it presents and describes THE qualities of effective teaching through current teachers. I will not go in detail of the qualities now because they are presented through 49 techniques that Lemov distinguishes in his observations, but I can bring the book to our next class and maybe summarize a few that I have read.

money shouldnt be the objective, however...

while i agree that teachers should not be teaching solely for the purpose of money, i do think that we should take into consideration the fact that it becomes difficult for a lot of people to opt to teach when they need to support themselves and potentially their families. teaching takes up a lot of time, making it near impossible to get a second job along with it, resulting in qualified people getting paid barely enough to allow them to get by. -- this is what deters people from the job, and we end up losing a lot of potentially dedicated, qualified teachers.

Catering to students feelings?

I think teachers should incorporate ways to make students more comfortable in classroom settings, yet allowing a little frustration can actually lead to fruitful things. When something is frustrating me I tend to chew on it for quite some time and often new ideas/perspectives emerge. Perhaps the focus should be for teachers to provide some helpful tools to trudge through frustration/challenge that comes with learning. Overcoming hurdles may provide more satisfaction in the end rather than making a student happy or constantly catering to their wants; the "real world" doesn't cater... Pushing the comfort zone is necessary for growth.

Small Group Notes: Lars, Jessica, Mae, and Simone

The group this evening consisted of Simone, Jessica, Mae, and me.

-We spoke about the need to get students in the classroom and have teachers who are engaging those students so that the students can graduate.

-Then we spoke about how efforts to improve schools and education, even if these efforts cannot effect students in some areas, are still important and may have a positive effect on education as a whole.

-We questioned the effect of Teach for America and other fellowships that sent bright and energetic young people to schools to teach for short periods; we are agreed that there are pros and cons...pros include having good, young, well educated teachers teach...and cons included having many of those teachers fulfill the commitment and never teach again, or one-up teachers who have been in the system for a while

Consensus: -Teachers should be held to higher standards, and part of that may involve teachers being perceived differently and more appreciated by society

-We agreed that tests are not necessarily indicative of a student's knowledge

Education like

Education like evolution

· Emergent purpose and learning

· Some practices and assignments seem useless and stupid—but, in the future, you can often turn around and say how it was useful and contributes to your understanding of things now

· It’s like starting with basic features of an organism, a light sensitive spot, and moving forward until you have an eye…

o You build and build and build and never really stop; it’s continuous and, even if there really is no purpose there, no guiding hand, we have the ability to turn around and note what was useful to us in the past and how it contributes to our present—and even how features now might contribute to our future

I also want to speak on my own experiences with "feelings" and a conscious understanding of them which, I think, are a little... "quirky." Quirky brain.

I have SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus, and as a result I have lots of fun symptoms that interrupt my life. One of them is anxiety and related dissociative states: depersonalization and derealization. There are random moments when, for no rhyme or reason, I am suddenly launched into a dream-like state. Nothing around me seems real or, worse, I don't seem real. Everything was a movie that I watched and didn't actually participate in; my body moves and acts and interacts with the world around me, but I only observe-- I didn't actively take part. It's very bizarre and very unsettling and, for a while, usually ended in a panic attack.

But, with the help of a few understanding doctors, professors, and family members, I began to understand the world and my brain and the constructiveness of everything. By identifying these experiences for what they were (dissociative, DP/DR), and by linking them to my lupus through temporal lobe epilepsy (a not uncommon feature of SLE sufferers), I began to control my reaction to these unsettling events. They still happen and I still notice them, but as I learn more about my brain and by understanding that sometimes random electrical activity just makes me feel unreal-- that didn't mean that reality was dissolving around me or that I was going insane or having some kind of psychotic break. But understanding and recognizing what was going on and the approximate reasons for it happening, I have stopped having as many panic attacks.

I still get anxious, no doubt. I still have the occasional panic attack. But when the world starts getting wobbly and things seem dreamy even though I'm awake, I'm able to take a deep breath and just know that it isn't the end of the world. I can role with it. And the events haven't been as bad, or I haven't noticed them as much. I've been slowly changing my reception of and reaction to them.

I guess, because of all of this, I am more than willing to acknowledge the brain as a construction, as the world as a construction, of no one, right reality. My experiences with TLE aren't wrong or crazy. They're just another perspective, another reality, another self.

And it's helped me develop my own interests and skills and paths. Not all bad, I guess.

Post new comment