Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Children’s Books and Graphic Novels: One Genre, Different Names

Children’s Books and Graphic Novels: One Genre, Different Names

Reading is part of the cycle of life. The cycle that comes with reading starts with parents reading picture books to their children and continues with chapter books once the reader is old enough to read on his or her own. For a number of years graphic novels have become a part of an emerging genre eagerly read by young adults and mature audiences depending on the subject. Scholars are paying close attention to graphic novels and the way images and text complement each other. Like children’s books, graphic novels would not achieve their purpose of telling a story in an clear, concise and innovative way if it images were not there to enhance the meaning of the text. With this being said, I believe that we have been reading graphic novels since childhood, the only difference is that the books we were read as children are known as a children’s book and the picture books we read on our own as adults have been given the name graphic novel by the scholarly community. As a bilingual student, I will analyze a children’s book I was read to in Spanish and another one in English and share my experiences versus reading Persepolis a decade later.

Images in children’s books are essential to the narrative because children have the tendency to pay a great amount of attention to them mainly because they are not yet capable of reading on their own. Children develop their imagination and the ability to identity objects and their colors, moods and emotions by just looking at images before they are able to speak. For children, reading picture books is an act of communion, they depend on someone else, most likely a parent or family member to read to them. As children grow older, there may be a disconnect between them and their parents, or whoever read to them because the next step in developing as a reader is to read chapter books which makes them grow out of the habit and need of being read to.

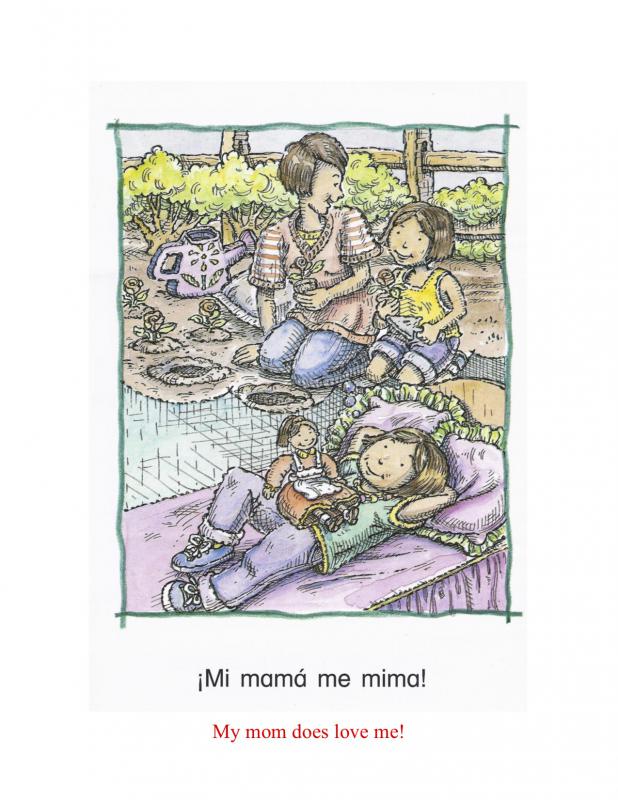

There is a certain novelty in picture books because the reader can write the story the way he or she wants to, provide a new caption for the image. These books normally have a picture and very little text. The image depicts the literal thing (s) that is going on, it tends to duplicate the meaning of the text, not enrich it. The image provides certain information the text does not, its job is to contribute something new to the narrative.

To prove my point, I have chosen two children’s books that are very dear to me: Mi mamá, Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) (I have attached two PDF files with translations) and Mo Willems’ The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog!

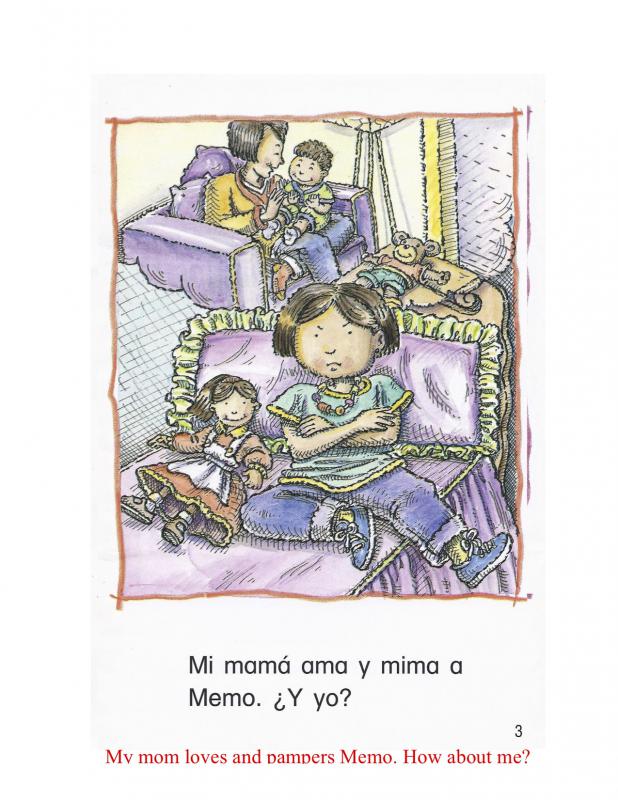

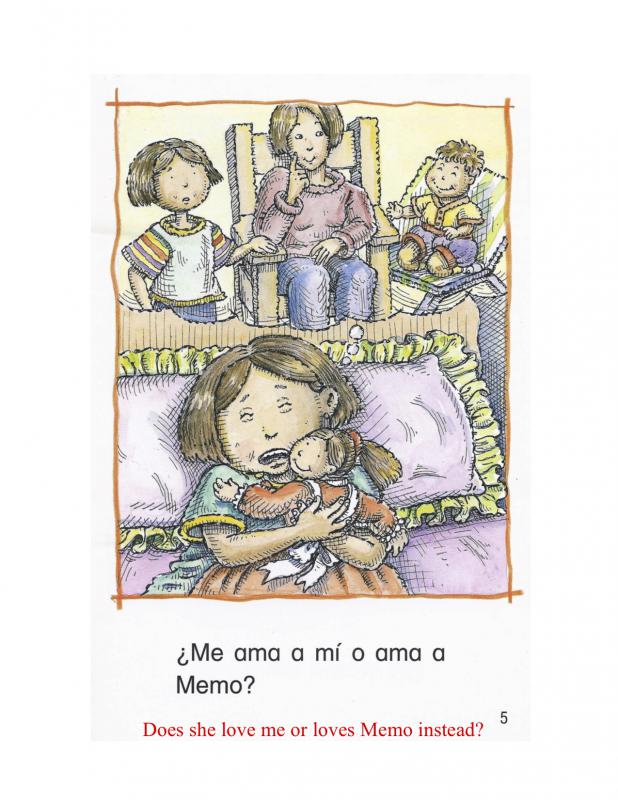

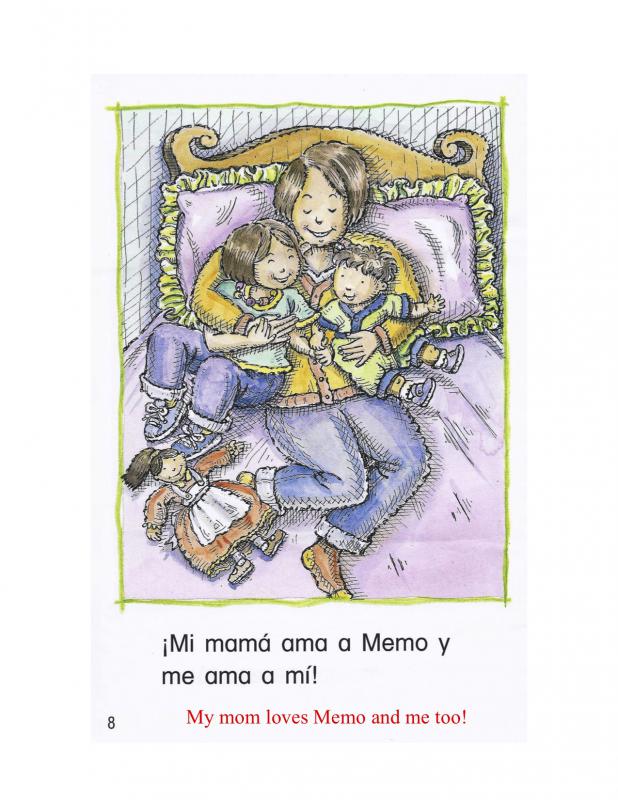

Mi mamá, Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) is a short story narrated by a young girl, this is why the title includes an “I”, who struggles to accept that she is no longer an only child. The author, Wanda De Jesús- Arvelo, was given the challenge of creating a short story by only using words that had the syllables ma,me,mi,mo and mu and the words "yo" (I) and "ayudo", (first person present tense of the verb “to help”). Having accepted the challenge, De Jesús- Arvelo, had to make sure her story was coherent and understandable for parents and children that are going through that particular situation, however, she knew her story was missing the key element that would help get the point across effortlessly: illustrations. With illustrations that go beyond words, the child can clearly interpret anger and distress and see the reactions that come as a consequence of acting that way. This can also apply to Mo Willems’ The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog! On the first page the reader knows the pigeon is excited about finding a hot dog: “Oooooh! A hot dog!”, I must add that the person reading to the child is most likely to know that an exclamation mark indicates excitement. The child now knows what being excited sounds like but he/ she may not know how to react towards excitement. It is important for the child to see the image that is with the text because that is the only way he/she can perceive the notion of being excited. The pigeon shows he is excited by vigorously flapping his feathers to the point that some fall off. After seeing the image and hearing what the pigeon says, the child can identify the reader’s tone of voice and vigorous repeated movements with being excited over something.

Scott Mc Cloud (Understanding Comics) addresses the previous statement, children do know what a comic is from an early age, they simply refer to it by a different name. In comics artists also appeal to the reader’s emotions, when reading Persepolis, there were times a times where I was able to gain a better understanding of what the author was trying to say if I read the image and the text individually and them the two of them together.

When I last interacted with children books, I was read to and mostly paid attention to the images that when put in a particular sequence told a story and not the small of text that accompanied each image. Compared to Persepolis, the experience reading it was different because my maturity as a reader has evolved since I last read those children’s books. The topics presented in tis graphic novel are meant for a more mature audience due to the fact it deals with Marjane Satrapi’s trials and tribulations growing up during a war in Iran and defying a society’s beliefs etc. The difference between Persepolis and the children’s books previously mentioned is that Persepolis includes pictures and text divided into panels. There are numerous short stories compiled into two large volumes that make up most of Satrapi’s life whereas a children’s book only has one story.

Both graphic novels and children books can belong to the same genre regardless of their length, Persepolis and Mi mamá, Memo y yo narrate someone’s life story, they share the structure of having a picture complement text and tell a story that way. The only new aspect that currently differentiates children’s books and graphic novels is the importance and dedication in which the scholarly community is studying the graphic novel. Even though scholars consider them an emerging genre, we have always been exposed to graphic novels; we just refer to them with a different name based on the time in our lives we read them. The cycle, the act of reading (the way a text is read and interpreted might) will remain the same.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| Mi mama Memo y yo PDF pages 1-4.pdf | 1.5 MB |

| Mi mama Memo y yo (PDF with translations pages 5-8).pdf | 1.97 MB |

Comments

The cycle of reading?

Alicia--

I'm teaching an environmental studies course in the fall which starts from the presumption that language is a link between natural and cultural ecosystems. So the first thing that strikes me here is your opening line--"Reading is part of the cycle of life"--which effectively turns a cultural practice into a natural one. I'd like to interrogate that claim, and prod you to complete it: Where does this cycle "go," for instance, after children learn to read on their own? What happens to adults, to the elderly, in the "cycle" you gesture toward, but fail to describe completely? You end your essay by saying that we "just refer to" children's books and graphic narratives "with a different name based on the time in our lives we read them," but that "the cycle...of reading" remains the same. So then it's not a cycle, right, but just a point, infinitely repeated? I'm confused!

I'm confused, too, about exactly how you understand the relationship between words and pictures. In two adjacent sentences you seem to say two very different things: that the "image depicts the literal thing (s) that is going on, it tends to duplicate the meaning of the text, not enrich it" and that the "image provides certain information the text does not, its job is to contribute something new to the narrative." These are two contrary (I think?) claims: that images duplicate words, or that they add something to them.

The most interesting thing I find you doing here is claiming that picture books are our first experiences of graphic novels (under another name). What's interesting (to me) about that claim is the notion that we actually learn to read pictures first. But then we are trained to read words, and somehow forget our visual literacy?

Comics artist and theorist Scott McCloud defines his art form as “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer." Does that description apply to the two children's books you feature here? You say they differ from Persepolis because the latter includes pictures and text divided into panels--why isn't that the case w/ the children's books? With the gutters occuring between pages, as we discussed in class? (See KT's posting and egrumer's webevent elaborating on this idea....)

There's so much more to say in all these dimensions...!

images?

Alicia--

your attachments aren't readable. Can you re-scan those images, please, reduce their size, save them as jpgs, and insert them w/in your text? (See How to Add an Image to your Post for instructions on how to do this). Thanks!