Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Wisdom, Serenity and Free Will

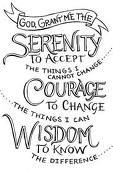

In Slaughterhouse-5, Vonnegut presents us with Billy Pilgrim, a man who was subject to all of war’s physical destruction and mental hollowing. Throughout the novel, Pilgrim wonders through in acceptance of all of the situations that are presented to him. He readily allows himself to be kidnapped by Aliens, he accepts when he will die and he accepts that he is in war. Despite the main character’s acquiescence, Vonnegut displays the Serenity prayer in the novel, a mantra of free will:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom always to tell the difference.

Does Billy (or do any of us) have the ability to follow this advice? The Trafalmadorians only follow the first phrase, acceptance, but Earthlings believe that we have the agency in all of these phrases. Is Vonnegut suggesting that Billy does have free will and that we can choose not to have war?

To explore this theme, I’d like to look at the contrast between the Trafalmadorian view of agency versus the Earthling view. The Trafalmadorians believe that the idea of free will is exclusive to those on Earth:

“If I hadn’t spent so much time studying Earthlings,” said the Trafalmadorian, “I wouldn’t have any idea what was meant be ‘free will…’ only on Earth is there any talk of free will.” [1]

They believe that, “All time is all time… it does not lend itself to warnings or expectations.” [2] As a result of this view, there is no agency for change, everything that is supposed to happen will happen, you cannot choose to go in a different direction, you must accept what happens because that is what is supposed to happen. The Trafalmadorians can only practice acceptance, not change.

By contrast, those on Earth think that there is free will. According to the Trafalmadorian,

“Earthlings are great explainers, explaining why this event is structured as it is, telling how other events may be achieved or avoided.” [3]

Further, at the beginning of his war experience, Billy would always tell his fellow soldiers, “’You guys go on without me,’ he said again and again.” [4] But he was always pushed on and they would never leave him alone or let him quit as he desired. In the beginning, we see that Billy was making an attempt at agency, he believed it was possible, but the war was too big for him to change, so he had to go along and accept it.

Given the contrasting views of agency for Earthlings versus Trafalmadorians, what can be gleaned, is it better to just accept that war is our “fate” or do we have free will to change that?

When Billy starts to accept the Trafalmadorian point of view, as seen by the fact that he doesn’t ever try to escape from the Alien Zoo or to alter the outcome of the events surrounding his death or try to prevent himself from being taken by the Aliens in the first place, his life becomes locked in. Whether or not he has any free will is of no consequence, he just accepts everything that comes to him. He learned this in war when he tried to express free will to quit, but it was not possible, so instead he’s learned to accept all that comes to him. This is the heart of the Trafalmadorian outlook, where they have wars but dismiss their consequences because that’s just the way that it goes. Their serenity is, “to accept the things I cannot change.” But putting this in conversation with free will, what could be different if we have the courage to change?

Currently, both points of view can result in war, but what if war was not glorified in movies and TV and Billy’s fellow soldiers didn’t drag him along in the war, what if war was not thought of as something to just accept? If you have the courage to make a change and enough people have that view or can be convinced of that view, then war would not be inevitable, it would be unacceptable. What it means to have a free will is to believe that you have a free will, otherwise you’re just subject to “the way things are supposed to be” and the bad things can never change. The Trafalmadorians will always have war. There is a well-known quote by Edmund Burke:

All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.

If you don’t believe that you can do anything then how can you do anything?

In looking at the final phrase of the Serenity prayer, “the wisdom always to tell the difference,” wisdom is developed through experience. Billy experienced a lack of free will in the war so his view of his ability to make a difference is skewed in favor of acceptance rather than change. But what happens to Billy’s outlook if he was able to have the experience of free will? Might his wisdom be that you can change war if you don’t glorify it and go along with it?

Bibliography and Works Cited

[1] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (location 1020-23)

[2] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (loc. 1015-20)

[3] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (loc 1015-20)

[4] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (loc 418-22)

Pic: Fate, City Limit - [Google images: Determinism - William Lane Craig]

Comments

Another thought...

This story has sections of truth and fiction. The fictional parts include biographical details of Vonnegut’s life. It also includes real life quotes or sayings from people like Theodore Roethke and Gideon Bible. I don’t know why there are so many but I think it affects the style of this story. I question whether a supposedly science fiction novel gives us wise quotes about fate or free will. Anyway I thought I would add my thoughts. I’m not sure if they are helpful to you or not.

Choosing Determinism?

KT--

You focus here on the key problematic of Slaughterhouse-5, one that we puzzled over together @ length as a class: are we to follow the advice of the Trafalmadorians, or read them skeptically, satirically, as articulating a position that Vonnegut is warning us we should position ourselves against, as we organize ourselves to do pacifist activism? If war is, indeed, unacceptable, what do we do to make it not inevitable? How do we act?

Your reflections include the interesting notion that "what it means to have a free will is to believe that you have a free will," that "otherwise you’re just subject to “the way things are supposed to be.'" Can we interrogate that claim a little more? Does believing something is true make it true? ("Seeing is believing"--but is believing seeing?) Mightn't a belief in free will be just an illusion…we act, thinking our acts make a difference, not realizing that all we do has been determined, has been, will be…?

For me, one of the most interesting questions here has to do with the role of fiction in the freely-willed world that you visualize: what contributions are being made, by novels like Slaughterhouse-5? Would you call this Vonnegut's act of free will (freely imagined)? Is the writing of fiction an enactment of free will, a refusal to be confined to what is and has been, a risk of imagining something "other"? Is it perhaps the paradigmatic example of freedom, to write the world differently? And so to make it different?