Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

It's Real

I was a child racked with nightmares. I spent many nights whispering for my dad in the night, sweating and stricken to my bed, wondering why he couldn’t hear me. I would dart down the hall to his bed and shake him awake “Daddy! Daddy, can I sleep with you?” I would gladly crawl into his bed, cuddle with my stuffed animal, and fall peacefully asleep. When I began to grow too old to be sleeping in my dad’s bed any longer, we had to have a talk. “It’s not real,” he said. “It’s all in your head. Just tell yourself in your nightmare that it isn’t real and I promise you won’t be scared anymore.” So my nightmares came less frequently and less intensely. I befriended the witch that hexed me and the ugly creature that always chased me turned out to have a sweet spot.

I became a woman racked with nightmares anyway. I dream I’m in a concentration camp, and I dream I’m kidnapped. I dream I’m whipped and I dream my loved ones die. I know that the events in the dream either will happen to me or have happened to someone else in the world. I don’t have a bed to run to and I don’t have comforting advice. Trying to tell myself ‘it’s not real’ doesn’t help anymore. These nightmares stem from influences everywhere - movies, books, history classes, the newspaper and my own fears.

I find that my childhood nightmares and my adult nightmares parallel my experiences with reading different types of stories. Reading words on a page is easy as long as I know how to pronounce them. Reading is not so easy. Difficulty, for me, lies in the digestion of what I read. I can chew, swallow and defecate a story about a boy wizard, but when I read historical fiction, I am sick with word vomit. Anything I take in seems to come back up again. I can deal with the boy wizard’s story, which contains fantastical creatures and events that are not known to exist. They are not ‘real’. A nightmare I have about Harry Potter is dismissed. On the other hand, I can’t and I don’t deal with The Help. There are no comforting words, and there is no option of dismissing what I read. Instead I am left chewing, swallowing, and vomiting and feeling pressure to find a cure for my sickness.

Huge questions follow. Why do stories affect us sometimes more than experiencing it in real life? Why tell stories based on events that actually happened? How is reading a novel different from getting the same story through a different media? Ultimately, why do we read and what do we expect from ourselves when we read? For me, reading a story about the suffering of people that actually happened distills a feeling of uncertainty in me that I don’t experience when someone I know is hurt in real life. I read stories about things that actually happened because they are compelling by nature, and so circulating these types of stories is also compelling by nature. Hearing about a story on the news or reading about it in a newspaper is less personal than reading the story in a novel. Ultimately, I expect more than I think I can accomplish since reading these types of stories arises feelings of large responsibility and feelings of smallness at the same time.

Stories about events that actually happened are compelling by nature because everyone has a little arrogance. We are amazed that an average person would transform into a perpetrator of genocide. We are horrified that a father would rape his children. We are stunned that policemen in the South would participate in lynching and get away with it. We think, What were they thinking? That’s horrible. We want to read about these situations because we think of them as an anomaly, or we think that humans have learned since then. Most of us are too arrogant to realize that they are sometimes reports of the norm, not the exception. Furthermore, most of us are also too arrogant to realize the stories can most certainly happen again in a different flavor. Humans don’t learn from their mistakes or the mistakes of others. We may be weeding out prejudice against blacks, but we are just replacing that with prejudice of homosexuals. Thus we want to read because we view stores about real events as exciting, fantastical stories.

Reading a book, especially historical fiction, is very different from experiencing the same story in the present. A person knows how they are reacting to a person’s suffering in the present. We know our role in someone’s pain. It may make us upset to see someone close to us being hurt by someone else, but I think the unknown factor that comes into play when we project ourselves into a story is sometimes more unsettling. When we put ourselves in a book setting, we could be anybody. So much of the environment determines who we are. The person I am today is not the person I would have been 50 years ago, and what I do today might not be what I would have done 50 years ago. In the example of The Help it is fear of being the one who is doing the mistreating that feeds the unsettling feelings.

Reading stories in a novel based on events that actually happened is more personal than getting that same story through a different media or in present. Considering the example of the treatment of blacks in the South in the 1950‘s, this story has been told in the news and newspapers, in documentaries, and has been captured in the novel The Help by Kathryn Stockett. In this case, the story was most effectively told in the form of a novel. This largely results because the relationship that a reader has with a novel is very different compared to the relationship a viewer has with the news or a documentary.

There is a large degree of abstraction in the news. The stories are reported blandly by reporters who look fake with their caked on makeup and stiff dress and who use the same facial expressions no matter what emotion their report describes. As a result, it is easy for viewers to distance themselves from the stories that they hear. The perpetrators and the victims seem far away, in some town or country that is dissimilar to our own. Also, each report is followed by another story back to back. Therefore, it is easier to pass over a story and move on, just as the news channel did.

Documentaries, or extended news reports, of the same story have more depth than a news report, but there is still a significant distance between the story and the viewer. Documentaries are longer than news reports and include some background information about the victim. Thus the viewers are more invested in the characters in a documentary than in a news report. Facial expressions of pain are more touching to a viewer than hearing a reporter say that the family is devastated. However, there are limitations to how extensively a documentary can touch a viewer. Documentaries usually have a narrator who uses simple language in order to explain the situation to a wide audience. Sometimes people are interviewed. Either way, as a result, there is a formality and a structure to the story. The narration distances the story from the real people that make up the story. The interviews and simulations are staged and they come off as aspects of TV drama. This distracts the audience from the content of the story.

The experience of reading a novel is quite different. A novel is not a report and it is not just the telling of a story; it is the envelopment of the reader into the world created by the book. We get to know the environment and context of the events. We become familiar with the characters, we love the characters for their pride, their struggles, their personalities, their sadness, their successes etc. The story is told in our own voice, not the voice of some narrator we can’t see or a robot-like news reporter. There is depth to the story and the interactions of the characters are not staged, but constructed to be believable. When the novel includes victimized characters, the characters’ pain becomes our own pain. As a reader, we have no control over what happens to the characters in the book or their actions, but we feel the need to defend or protect the characters from what is hurting them. This desire to protect leaves me confused when I read books based on events that actually happened.

When I read The Help, the characters’ pain was my pain and very separate from my pain at the same time. I love the character Aibileen, and so when her feelings were hurt, it affected me. Yet, I am my own person and there is an Aibileen in real life that is her own person. We each have our own experiences. It is a challenge to identify with anyone in the book because in actuality, I would be another character in the book and I would have my own actions. This is where feelings of large responsibility grow. Ultimately, I have a difficult time deciding what the characters in the book would want and what I want from myself, and this is the source of my feeling of smallness.

The Help is a great example of a book that leaves readers emotionally exhausted. It introduces the reader wonderfully to the world of the South in the 1950’s. It is filled with beautiful Southern women and old fashioned dresses, dainty homes and hot weather, Southern manners and Southern pride, charity and card games - and a large dose of ugliness. Like any historical fiction book, readers use their imaginations to project what they would be like in the time period. Would we be plantation owners? Politicians? Would I really drop out of college to get married? Would I learn to sit pretty and play bridge? Well, there’s no question that my family would have a maid - everyone did, right? That’s how it was back then.

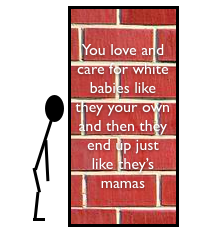

We all don’t want to think that we would be guilty of some of the things we know went on in the South, but at the same time we know that’s not realistic. A prime example is the theme in the story in which the white babies love the black maids who raise them and then those white babies grow up to turn out just like their parents, thinking that the coloured are lesser human beings. The children are taught to think this way in school and by their parents, and so when they grow up, they believe the lies about the coloured. This part of the story can’t be overlooked because I have already lunged into the story. I have already wondered what I would be like, who I would be. Of course, we all want to identify with Skeeter, who is a white character in the story who is pro-civil rights, but would we be like her? Thus, when I read The Help I felt a large responsibility to decide who I would be and how I would act. I felt a pressure to do something now - to analyze myself in the present and see whether I mimic any of the cruel thoughts or actions of the Southern women in the story.

Besides deciding who I would be and how I would act, there is also a large call to some sort of larger political action. In Extremeties by Jason Tougaw and Nancy Miller, they describe it well. They suggest that “these painful stories about deterritorialization, decolinization, people pushed past the margins, bodies brutalized, children victimized, populations dying, in exile - suggested a world of subsemantic history that demands the weight of political speech,” (29). We are accustomed to protesting against the force that is causing these pains, which is usually a government, or demanding that the government (which we think of as more powerful than ourselves) intervene in the injustices. Either way, political speech in America is a worn out option for acting against suffering. It is an old option that we feel pressured to use when we are faced with new kinds of hurting in the world.

Feelings of smallness result from this overwhelming feeling of responsibility and an appeal to action. I didn’t know how to react to the message in The Help. All I came up with was pity and shame at first. Well, the maids don’t want my pity - they are too proud. I don’t make any progress feeling shameful of people’s actions in the past. This pressure to decide how to digest these stories increases our feelings of smallness. So how are the feelings of large responsibility and smallness of impact reconciled to satisfaction?

The authors of Extremeties state, “ we inhabit an academic world that is busy consuming trauma - eating, swallowing, perusing, consuming, exchanging, circulating, creating professional connections - through its stories about the dead,” (29). This is the epitome of how the academic world deals with feelings of large responsibility and smallness of impact. Some of us write stories or tell stories, but either way we relay them on. We talk it out. Maybe we think that the story is important for people to know, or maybe we think that retelling it is healing. I am guilty of this academia-like practice. I tell stories to see others’ reactions to the story. What do they think? Do they care as much as I do? Each time, I hope that sharing stories helps me process them better.

Others might read more stories of a similar flavor. I think this dampens the shock of reading the first story. Instead of the initial reaction of How could this happen?!, readers begin to see that there are lots of examples of [this] type of hurting in the world. Oh that used to happen a lot. The next time we tell that story, we will assume a certain degree of nonchalance, Been there, cared about that already.

So, I deal with stories of hurting by waiting. I wait for the shock and the pain to become numb. I tell the story again, I reread the book, I talk about it and I avoid it. The reason for this is that I have trouble getting past even one line in a book or one scene because they stare me in the face saying, “It’s real.” When I was reading The Help I didn’t read it all at once. I read it slowly because sometimes it was too much to handle. I had to put the book down and walk away. I didn’t necessarily learn how to handle what I read in my time away from the book. Instead, I think those things in the book that I hadn’t hashed out in my time away were things that I pushed to the back of my mind. My reconciliation is that I think I can’t care about everything, right?

Well, this is probably why I get nightmares. I have a fear for myself and for others about experiencing the hurting that I read about, and I fear that I will cause someone else’s hurting. I fear that these issues can’t be solved because I don’t have the capacity to even reconcile them within myself. Moving from this point of recognition that I don’t usually effectively deal with stories about hurting, what can be accomplished from here? I am not one for political speech, but I am a person who likes closure. My closure for now will be recognizing that I don’t deal with real stories when they are about suffering.

Comments

A little about this essay

Writing for me has become a process of reflection on what I know and what I want to learn. It has left the confinements of an assignment and become an exploration of myself and how I relate to pieces of writing. In this essay, I had great difficulty capturing how I felt about my topic in words only. I added in the pictures as part of the essay to illustrate the emotions described by the text. The picture at the end is meant to show my flavor of contentment. I am happy that I found a conclusion, but I know that with this conclusion only come more questions and more work. Thank you for reading.