Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Genres Web Paper 3

Science in Science Fiction: A Proposal

My tongue is “jumbled and jangled”1. Growing up speaking Arabic, English, and French, I am most self-expressive juggling between all three, casually in conversation. I relate feelings and emotions with specific language expressions that are meaningless if not incomprehensible when translated. The importance in the phonetics in the Arabic language allows me to translate my emotions in the stress of the sounds in words. Saying “stupid” in Arabic is not only the same word for “ass” but also has an “h” sound that resonates from the roof of your mouth, as if having a bundle of red chili peppers scorching one’s throat while shouting out a sharp “HHH’OT!”. I cannot however participate in a serious, intellectual discussion in Arabic but rather speak English, my language of education, from which I have learned the big words and forms for argumentation. First learning French from TV or overheard conversations between my parents, I speak it to communicate my work and education to those who do not understand English. All three languages have become inevitable pieces to my language and cultural puzzle that intertwine to translate my thoughts and ideas to others.

Apostles of Mercy: Aliens and Agency

A note on citations: The War of the Worlds is in the public domain; as such, I read it online, in a digital edition that lacked page numbers. This makes citation somewhat tricky. I have chosen to cite by chapter number, as consequence, both for The War of the Worlds and (for the sake of consistency) for Slaughterhouse Five. Thus, in Slaughterhouse Five, parenthetical citations are author and chapter number (Vonnegut 1) and in The War of the Worlds parenthetical citations are author, book number, and then chapter number (Wells I, 1). If this is unacceptable, I can change it. However, I find that I rather like this form of citation. Considering the differences in pagination in various editions of the same book, it does not make things much more difficult to reference than page numbers would; either method would involve some flipping through pages to find the quotation cited.

A magical adventure with reality

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the genre of magic realism as a “literary style in which realistic techniques such as naturalistic detail, narrative, etc., are similarly combined with surreal or dreamlike elements (www.oed.com).” This is clearly not a genre we looked at in class, and yet it is not all that different from other genres we have studied. For example, the OED defines science fiction as “imaginative fiction based on postulated scientific discoveries or spectacular environmental changes, freq. set in the future or on other planets and involving space or time travel (www.oed.com).” If magic realism is the combination of realistic and surreal elements and science fiction of fictional and scientific elements it is not unfounded to say that these two genres are cut of the same cloth.

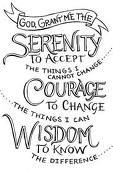

Wisdom, Serenity and Free Will

In Slaughterhouse-5, Vonnegut presents us with Billy Pilgrim, a man who was subject to all of war’s physical destruction and mental hollowing. Throughout the novel, Pilgrim wonders through in acceptance of all of the situations that are presented to him. He readily allows himself to be kidnapped by Aliens, he accepts when he will die and he accepts that he is in war. Despite the main character’s acquiescence, Vonnegut displays the Serenity prayer in the novel, a mantra of free will:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom always to tell the difference.

Does Billy (or do any of us) have the ability to follow this advice? The Trafalmadorians only follow the first phrase, acceptance, but Earthlings believe that we have the agency in all of these phrases. Is Vonnegut suggesting that Billy does have free will and that we can choose not to have war?

To explore this theme, I’d like to look at the contrast between the Trafalmadorian view of agency versus the Earthling view. The Trafalmadorians believe that the idea of free will is exclusive to those on Earth:

Literature LABS

Very often I turn to my friends at the dinner table and say, “You know what would be cool…” or, “I have this great idea…” or, “What would you guys think if…”. Very often ideas pop into my head and I spit them out like rotten cherry tomatoes. What makes them rotten is because as soon as dinner is over and we leave the table, the idea leaves my mind or I become disinterested. The idea rots. But, not this time. I refuse to believe this idea will become rotten, and I’ve instead committed to its growth: I will create a literary lab that applies the scientific method to story creation, and I’ve devised a model and a 4 step guide to making it a reality.

Literature LABS

Biology Principles as They Apply to Film

The world of Hollywood is very intense and cut-throat, each person trying so hard to be more unique than the next. With well over several decades of history and probably thousands of brains that have contributed to the success and reputation of Hollywood, screen writers and movie producers are trying more than ever to be unique and original. However, as much as society pretends that it is not, Hollywood is still very much a part of life, a part of biology. Years and years of studies have established biological concepts on survival and fitness that not only apply to humans and living things, but also apply to the elements that are part of our lives, just like entertainment and film. More specifically, the principles of adaptation that the discipline of Biology has well established can be applied to film, and has been used to successfully transform novels into film, as shows by the movie Adaptation, which was very loosely based on the novel The Orchid Thief by Susan Orlean.

a great-grandstory

My Bibbie invented Gabazoogoo the Talking Dog when his grandsons were little. My sister and I, Bib’s first great-grandchildren, grew up with Gabazoogoo too. Stories rolled effortlessly off of Bib’s tongue, and when he spoke, it felt like I could sit still for an eternity, mesmerized by wisdom. I knew that Gabazoogoo was make believe, but Bib had knack for combining the fantastical with the very real, and I know his stories helped me to learn this world.

Discovering Henrietta Lacks

For this webpaper, I have made an artistic rendition of "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks", inspired by Kim Northrop's Neil Gaiman-inspired paintings. To accompany this, I have also played with my writing style. Once upon a time when I was in Year 10/11 (so the equivalent of high school freshman/sophomore), I did a GCSE course in fine art. We had to document our work, and I used this style to present the process that I used to create my piece. Within this style, however, I have used others, such as a letter format to communicate my ideas. With this documentation in the form of a "portfolio" of sorts, I hoped to parallel the method that Rebecca Skloot used to write her book. However, a lot of the things that I have written are ironic in the sense that I take the book as full "truth". But, my final piece changes this a little bit as I use it to problematize Skloot's first line: "This is a work of non-fiction."

I've put images of the final piece and the pages from the "portfolio" here rather than embed them into Serendip as the image size was too big. Just click on the pictures and you'll see a bigger version of the piece!