Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Story of May

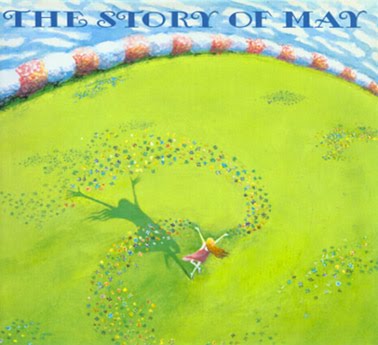

The Story of May by Mordicai Gerstein was always a favorite of mine as a kid. This short and sweet picture book tells the story of a little girl, the month of May, and her journey through the year to meet her father December. She leaves her mother April’s side and meets all of her relatives in an “exuberant story of familial love set in the richness of the passing seasons” (HarperCollins Publishers, inside cover). I choose this book because of the wonderment of earth, nature, and the seasons it helped instill in me as a young girl. I so easily connected with May, and I believe her journey of play and independence helped me ‘access’ a new version of the world, one in which nature and the environment are paramount, and everything flows together calmly with time. The stunning watercolor illustrations came to life in my head; when I see them now, I’m surprised that the pictures end where the page does, and don’t all carry on endlessly.

The Story of May by Mordicai Gerstein was always a favorite of mine as a kid. This short and sweet picture book tells the story of a little girl, the month of May, and her journey through the year to meet her father December. She leaves her mother April’s side and meets all of her relatives in an “exuberant story of familial love set in the richness of the passing seasons” (HarperCollins Publishers, inside cover). I choose this book because of the wonderment of earth, nature, and the seasons it helped instill in me as a young girl. I so easily connected with May, and I believe her journey of play and independence helped me ‘access’ a new version of the world, one in which nature and the environment are paramount, and everything flows together calmly with time. The stunning watercolor illustrations came to life in my head; when I see them now, I’m surprised that the pictures end where the page does, and don’t all carry on endlessly.

The story opens with May asleep in her hammock bed hanging from a willow tree being woken by her mother April, a tall beautiful woman in a flowing earth-colored dress and long hair. Today is the day that May will learn the “certain things a young spring month is expected to do… to scatter wildflowers…welcome returning birds, and … make cherry and apple buds swell and blossom” (Gerstein). This is the day that May is given her responsibilities she has as a month of the year. This new responsibility establishes Gerstein’s story as one of discovery and independence and growing up. Because it is set in the world of nature, the outdoors, and the seasons, The Story of May is an example of play in wildscapes.

The eccentric family members that May meets on her journey promote a positive and fun view of having deep connections to the environment. Most of the ‘months’ are adults, family members and thus caregivers to May, yet they all represent a direct connection between life, play, and nature. Nearly the entire book takes place in the outdoors. Nature defines their lives; their lives do not define nature. Nature is the world, not something you find if you go outside.

In fact, grandmother November and father December are the only two months to have indoor abodes. They are surrounded by nature, and not removed from it the way our society urges, dare I say requires us to be. Thus, the ‘nature environment’ is the dominant setting of May’s entire world.

The first month May meets on her journey is her aunt June, “a brown-armed woman with a wheelbarrow. Her green-velvet dress had countless pockets, all full of seed packages and twittering baby birds” (Gerstein). June shows May her beautiful garden of flowers and vegetables, and says to May:

“‘Some say vegetables must be eaten as soon as they’re picked, (b)ut the deer and rabbits taught me to eat them before they’re picked’” (Gerstein).

The illustrations show May and June nibbling greens off from the vines along with the rabbits and deer. This short segment of May’s story carries a powerful message. It brings the idea of local food into a whole new perspective. It reminds us, or perhaps teaches the child for the first time, that we, too, are animals. We are not the supreme rulers of this earth, and there are things that we can learn from animals and how they choose to interact with the environment.

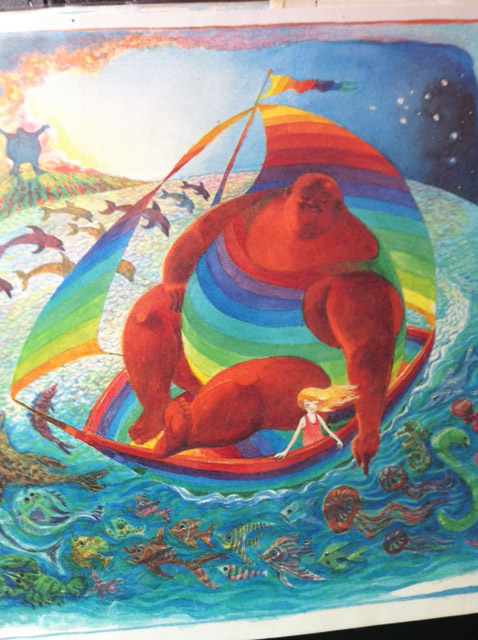

May and her relatives are grand personifications of months. All of May’s newfound relatives are illustrated as ‘larger than life’; May looks like a Borrower next to them, and is shown multiple times being held like a baby or a cat. These personifications play a heavy role in building a child’s connection with nature. Rather than asserting a control that humans have over Earth and the environment, I think this personification helps to give a voice to the changes of nature. The seasons, and weather patterns in general, are often considered as having very ‘human-like’ properties, and Gerstein voices that. By having a child as the central character of the story, children reading can relate to her and the positive connection that her family – the environment – have for her. We discover a new world along with May, hopefully witnessing the connection between her world, an ultimate unthreatened environment, and our own. May’s interactions with her environment are graced with welcoming smiles, laughter, singing, and joy of close family. Thinking of the environment in terms of a family, paying it the respect you might give a loved one can strengthen a child’s connection with nature and build an understanding of their own roles in the interconnectedness and balance of the environment.

May and her relatives are grand personifications of months. All of May’s newfound relatives are illustrated as ‘larger than life’; May looks like a Borrower next to them, and is shown multiple times being held like a baby or a cat. These personifications play a heavy role in building a child’s connection with nature. Rather than asserting a control that humans have over Earth and the environment, I think this personification helps to give a voice to the changes of nature. The seasons, and weather patterns in general, are often considered as having very ‘human-like’ properties, and Gerstein voices that. By having a child as the central character of the story, children reading can relate to her and the positive connection that her family – the environment – have for her. We discover a new world along with May, hopefully witnessing the connection between her world, an ultimate unthreatened environment, and our own. May’s interactions with her environment are graced with welcoming smiles, laughter, singing, and joy of close family. Thinking of the environment in terms of a family, paying it the respect you might give a loved one can strengthen a child’s connection with nature and build an understanding of their own roles in the interconnectedness and balance of the environment.

May experiencing a form of play that allows her the independence of exploring new, unfamiliar territories unsupervised by her primary authority figure. The forms that her experiences take are echoed in Tim Edensor et al.’s advocacy of play in urban wildscapes. They assert that “rather than risk being seen as integral to the value of play, playful activities for adults and young people are commonly seen as dangerous infringements on other, responsible, productive uses of public space” (Tim Edensor et al 74). May is unencumbered by these issues, for the ‘nature world of months’ that she lives in celebrates play and risk. May skis down a mountain with her uncle January, “swerving right and left around snow-crusted pines”, skates across a frozen lake with her aunt February as the ice begins to crack, and rides “strapped to a great silver-and-blue kite” with her cousin March (Gerstein).

As May finds her place in her family, and learns her responsibilities as the month of May, the child reader also finds a new way of reading the world. Nature is where we all live, no matter how disguised and processed and modernized it may be, and the environment is something that must be protected like family, because we are all part of the same family: earth.

Comments

access to a new version of the world

Sophia,

Your paper opens with this notion that this book actually gave you ‘access to a new version of the world’ – a phrase that highlights both the idea that access can come from many sources and the idea that ‘the world’ isn’t stable but rather can be perceived/experienced in different versions. These two points seem to me key to an exciting approach to environmental education. And how interesting that you remembered the pictures going off the page…!

This causal connection -- “Because it is set in the world of nature, the outdoors, and the seasons, The Story of May is an example of play in wildscapes” – seems to me a little loose and I’d like to see you do more with this. I’d say that “wildscapes” as we’ve read about and discussed them are not exactly the ‘pure’ nature that it sounds like you’re talking about here; rather, “wildscapes” as used by Edsenor, Mugford, etc. seem to be characterized by their simultaneous “natural” and urban or human-made qualities – kind of a borderland or cross-over space. If “nature is the world, not something you find if you go outside,” what does this mean about what humans do that impacts the environment? Is that outside the scope of this book, or might you construe some implications from the book…?

Also complicated and interesting are the juxtaposition of these two points: “We are not the supreme rulers of this earth, and there are things that we can learn from animals and how they choose to interact with the environment,” and the ambiguous role of humans as months. These both feed an overall sense of “connection with nature” and nature as family. This last point reminds me of a talk I heard last summer by a Native American environmentalist who used the language of family – specifically, our “relatives” – in talking about humans, animals, and our “environment.” You get to this nicely in your conclusion about learning to “read the world.”