Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Empathy and Dialogue

empathy—the ability to understand and share the feelings of another

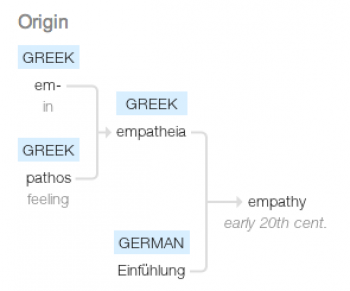

Empathy is one of those qualities that we’re constantly told that, as “good” people, we should possess. From elementary school character education to high school literature classes, one purported purpose of education (at least in my American public school experience) is to teach us how to care about and understand the feelings of other people. I’ve always considered myself an empathetic person, someone who cares about and understands others’ feelings, but lately I’ve been questioning whether this quality I’ve prided myself on even exists. Is it ever possible to truly “understand and share the feelings of another”?

For the rest of this paper, although it cannot be proven in any way outside of my own gut feeling, I am going to write based on the assumption that the answer to this question is “no”. Part of me, the sociologist part that believes in structural change and questions the extent of individuality, resists this answer, because isn’t saying that people can never understand and share each other’s feelings asserting the difference of individuals and therefore the importance of change on the individual level? But, upon reflection, I have come to believe that saying that people are individuals doesn’t mean that we don’t participate as a collective in social systems, or that meaningful social change will happen on the individual level. It just means that we are separated from each other, by our physical bodies and our socially constructed experiences, and that our imaginations can only build upon the foundations of personal experience when trying to understand each other. Social systems reinforce our inability to understand each other’s feelings, by positioning us differently according to our different identities, and therefore giving us different experiences fundamentally not understandable to people who don’t share them. Together we create and maintain systems that affect all of us, and individually we are trapped inside of our own minds, forever unable to fully understand how others feel.

If it isn’t possible to understand and share the feelings of another, if we have rejected the definition of empathy and therefore empathy itself, then what are we left with? There is, of course, always sympathy, which can be defined as “feelings of pity and sorrow for someone else’s misfortune”. But the idea of sympathy doesn’t seem to fully encompass the range of emotions we are able to experience when confronted with someone else’s feelings. For one, sympathy and pity in some situations have connotations of power, of feeling sorry for someone else because you perceive your life as somehow better than theirs. In this way, sympathy can, although it doesn’t have to, imply a fundamental lack of understanding of someone else’s feelings and experiences, if you assume that their life is somehow unfortunate because of your standards of what constitutes fortune. Sympathy is also an outwardly focused concept, implying that the emotions that we have about others’ emotions are directed toward them and not toward ourselves. But I always react the strongest to other people’s feelings when I love them, or when something about their experience shatters the worldview that I had previously possessed. At those times, what I am feeling is as least as much about me as it is about the other person, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. If we’ve rejected empathy as a concept, then how else are we supposed to relate to other people besides how we feel about what they’ve experienced? There doesn’t seem to be an English word for this combination of outward and inward focused emotion, sympathy and something else. But it seems certain that empathy isn’t correct, because our attempts to relate to each other always fall short of complete understanding.

If we can never fully understand anyone’s experience besides our own, then what does it mean to engage in social justice work, with the goal of liberation not only for ourselves, but for people whose feelings are on some level unknown to us? To consider this question, I first want to talk about dialogue, which, while by no means the only tool of social justice work, is a prominent and popular one. Activists are encouraged to talk with people who disagree with them, often for the purpose of finding common ground or understanding the other side, and those who refuse to engage in this dialogue are often seen as angry, abrasive, responsible for their own continued oppression. Teju Cole speaks to this in his article “The White-Savior Industrial Complex”, in which he writes, “People of color, women, and gays -- who now have greater access to the centers of influence that ever before -- are under pressure to be well-behaved when talking about their struggles... Marginalized voices in America have fewer and fewer avenues to speak plainly about what they suffer; the effect of this enforced civility is that those voices are falsified or blocked entirely from the discourse.” In The Lives of Animals by J. M. Coetzee, Elizabeth Costello’s animal rights advocacy is rejected by many because she is seen as provocative and abrasive, since she refuses to engage in the accepted convention of polite dialogue.

The “enforced civility” of dialogue is often justified by claims that it’s important to understand what the other side thinks, which of course assumes that fully understanding the other side is possible. But if we accept that it is impossible to fully understand another’s feelings, that empathy as we define it does not exist, then what is the point of dialogue?

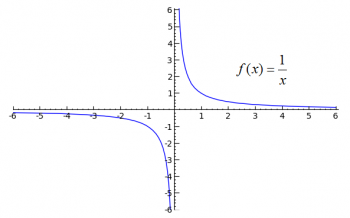

Perhaps, even though we cannot completely understand each other, we can come close. We can use our experiences as foundation, our imaginations for extrapolation, and come up with an approximation of another’s feelings, creeping closer to their reality as we have more experiences but never fully achieving understanding. We can visualize our trek toward empathy as a graph with asymptotes, lines such that the distance between curves and those lines approaches zero the closer they get to infinity. If this is true, then dialogue can be a tool that helps us inch closer to the hypothetical infinity, where the difference between other people’s feelings and our perceptions of them is nonexistent.

But even if dialogue can help us get closer to experiencing empathy, why is empathy important? What is the point of understanding what the “other side” thinks and feels? In her TED Talk “The Danger of a Single Story”, novelist Chimamanda Adichie talks about the danger of having only one story represent something, how that leads to stereotypes and misunderstandings and the story of the privileged becoming the only narrative. She says, “It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power... How [stories] are told, who tells them, when they're told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power. Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.” So perhaps, even if we can never achieve full empathy, the point of dialogue is to attempt to rectify the power imbalance that creates single stories. Perhaps dialogue can help us understand others’ experiences as best we can through their words, to ensure that we have as many stories in our heads as possible about people and things we do not know. But although I think dialogue has the potential to challenge single stories, I do not think it does so in its current most-accepted form, with its emphasis on politeness and productivity. In an earlier post, I wrote, “... the expectation that people are required to enter into "productive dialogue" with those who disagree with them, and that a fundamental part of that "productive dialogue" is politeness and respecting others' views even if you disagree, is often an oppressive construct. Many groups of marginalized people are too often expected to engage in productive dialogue or debate with people whose views are harmful to them, who doubt their humanity or whether they deserve rights, and if those marginalized people ever get upset or refuse to engage in dialogue they are labeled as "angry" and "extremist" and are blamed for their own oppression, because they aren't being polite or respectful. In circumstances like this, dialogue serves to support the existing power structure, to define the ways in which interactions should occur according to the status quo and force marginalized people into interactions that are fundamentally harmful to them.” I think that, if we want dialogue that moves us closer to empathy, if we want dialogue that challenges single stories, we have to do away with expectations of politeness, expectations that marginalized people should engage in dialogue with their oppressors for the purpose of their own liberation. If we allow dialogue to just happen instead of forcing it upon people, if we allow people to get angry when they have every right to be, then perhaps we will engage in more honest dialogue that will help us understand each other better.

I want to close by considering two examples of “social justice” work within the context of the question I posed earlier: what does it mean to engage in social justice work, with the goal of liberation not only for ourselves, but for people whose feelings are on some level unknown to us? In his article “The White-Savior Industrial Complex”, Teju Cole criticizes Americans who attempt to “help” people in non-Western countries, arguing that Americans should focus on changing the “money-driven villainy of American foreign policy” that harms people around the world instead of imposing “themselves on Africa itself”. Cole’s approach to social justice stems at least in part from the idea that, because Americans can never fully understand the experiences and feelings of people in Africa, their attempts to “help” them stem from the single stories they hold in their heads, images of Africa as a place that cannot save itself and therefore needs their saving. Our inability to experience complete empathy means that, if we want to work for liberation for groups we are not a part of, we need to take a back seat, listen to the people affected and respect their agency and, most importantly, think about how the groups we are a part of contribute to the oppression of others and maybe work for change at home instead.

In The Lives of Animals, Elizabeth Costello is also trying to “help” a group that she is not a part of. However, unlike the “white saviors” Teju Cole criticizes, Costello isn’t trying to help another group of humans, but non-human animals. If how close we can get to full empathy is determined by our common experiences, as we can only understand what we’ve been through and extrapolate from there, then it seems likely that we can empathize less with animals than other humans, because our experiences and perceptions of the world differ more. But, unlike the “white saviors”, no one seems to have a problem with the idea of Costello working for animal rights when she cannot fully understand their experiences and feelings. (People of course have a lot of problems with how Costello engages in this work, as previously mentioned, but no one ever raises the objection that people shouldn’t work for animal rights in general.) What makes us think that trying to help animals okay when trying to help other people is so often problematic? I think that, fundamentally, it comes down to agency. People like Teju Cole, who object to the work of “white saviors”, argue that those people fail to recognize the agency of people they are trying to “help”, but this isn’t an issue for animal rights activism, because no one believes that animals have agency in the same way. Maybe, then, a fundamental part of empathy, or of getting as close to empathy as we can, is recognizing that every person has agency—this is something we should be able to understand after all, as we all have agency ourselves. Maybe, if we recognize other people’s agency, we will stop falsely believing that they need us to save them.

Comments

the "universality" of poetry?

Kelsey--

here are my (rather extensive!) notes from our writing conference today: our reflections on the writing you’ve done for this class so far, and our shared sense of what you might do for your final project.

You said that your papers have “gotten larger in focus,” in part in response to the prompts, in part because of your own inclination to move from a personal to a structural frame of reference (and to figure out the relation between the two). The first paper was “about you,” the second “some about you,” the third not @ all…

The first one was also “not a conscious argument, just talking about stuff”; the second was “interrogating the complexities –and importance--of pride, once you locate it socially: one’s environment, in particular one’s privileged position in a given environment, affects whether--and how appropriate it is--to feel proud. You liked this one best, both because it was “personally located,” and because you were able to say some interesting things/”get somewhere” with it.

You were most frustrated with the third paper, which you described as your “most nebulous” one; you “didn’t know where you were going,” as you struggled with the implications of the assertion that full empathy isn’t possible. “What to do? How to affect social change? Does dialogue still make sense in this context? Can it “get us closer”? And “what’s the point” of just “getting close”? Your mother, who sees a major part of her job as “teaching empathy to privileged students,” responded to these questions with another: “if we reject empathy, what else do we have?”

Your proposal for your final paper was a surprise to me—and I can’t wait to see where it takes you. You have found yourself caught up by Nirmal’s use of Rilke’s poetry in The Hungry Tide; Nirmal is not religious, and/but Rilke seems to serve him as something of a spiritual guide….. So you want to think about how effective Nirmal is in using Rilke’s texts to make sense of a world that the poet didn’t know: Is this a form of translation? Into another context? What does he learn from doing this? Is he “going too far”? (“Taking too much latitude?”)

“Trying to see if you can figure out some of these questions,” you then want to see what “reading through Rilke” might bring to the light, as you reflect on our experiences in this cluster of eco-courses. You are interested in trying to use Rilke as a lens to read our 360 experience—and I think this should be a very interesting experiment!

You spoke, in this regard, about the “power of poetry,” being “general and universal enough that it can be applied to a range of situations”; you “really like it for its vagueness,” for its “metaphoric range,” its lack of a distinct narrative. There is a lot of power in finding that another has anticipated/understands/can relate to your own experience. Poetry of the sort you are talking about here (and there are of course other sorts) is, you postulated, “not a story.” You said, in this regard, that you might want to think more about the “difference between poetry and prose,” particularly given what we’ve learned about the “danger of a single story.” How are you not playing with that danger, when you speak of a poem as being “universal”?

Along these lines, I thought that you might want to take a look @ Adrienne Rich’s description of the evolution of her poetic practice, in her rather alarmingly titled essay, “When We Dead Awaken.” She describes a move from “the strategy of formalism” (“like asbestos gloves, it allowed me to handle materials I couldn't pick up barehanded”) to learning to write “directly about experiencing herself as a woman.” “I had been taught,” she says, “that poetry should be ‘universal,’ which meant, of course, non-female….”

So interested to see where you go with this!

Eagerly, and always,

Anne

Helplessness

A big part of your final two paragraphs has to do with the notion of helplessness. I hadn't previously put side-by-side Elizabeth Costello's passion for helping animals and the white saviour complex, so thanks for laying that out. It really makes clear the forces of assumed helplessness, pity, projected victimisation, etc. From what I understand, you say that it is more difficult or inaccessible for Costello to feel empathy for an animal, than it would/should/could be to feel empathy for another human being. However, despite this, it is more complicated and "problematic" when humans get involved helping humans than when humans get involved helping animals.

I suppose this has to do with the helplessness - or lack of agency - we project onto the bodies, human or animal, we want to help. Animals can't talk back and express their ableness and ability to stay alive in the midst of slaughterhouses and other threats to their survival. With other humans, however, we put up barriers between us and them as a sort of safety net (perhaps even in the econo-political sense with unemployment benefits, welfare, health care) that allow for us to see their vulnerability, system-caused victimisation, and helplessness. The problem is that there is a system in place that places and keeps humans in positions where they are categorized as needing help and assisstance because they can't help themselves.

If this barrier was more porous and socioeconomic mobility was greater, then we could hear each other's voices across the safety nets and other fences we put up around to keep humanity organised.