Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Gender in Children's Book Illustrations - Web Event #1

“Girl, boy, boy, boy, girl, girl, boy, girl,” I quickly say to myself.

“Girl, boy, boy, boy, girl, girl, boy, girl,” I quickly say to myself.

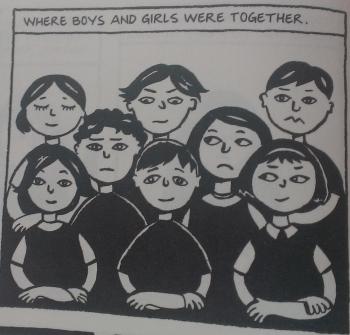

On the second page of Persepolis, there is a panel reading, “where boys and girls were together,” and the illustration shows eight children (Satrapi, 4). When I read that page, I stared at the drawing trying to figure out how I knew which children were boys and which were girls. I could tell, from a simplistic drawing, based on the hairstyles and the top half of the shirts, and that bothered me. The style of the drawings and the accessibility of Persepolis reminded me of illustrated children’s books: simple sentences with drawings of what is happening.

I decided to take another look at a few children’s books I loved when I was younger. Many children’s books feature anthropomorphic characters, and I wondered how the anthropomorphic characters would be gendered compared to the human characters. The specific stories I looked at were “The Veil” from Persepolis, “Chapter VII In Which Kanga and Baby Roo Come to the Forest and Piglet Has a Bath” from Winnie-the-Pooh, The Berenstain Bears and the Sitter, Arthur Writes a Story, Clifford’s Family, and Thank you, Amelia Bedelia. The illustrations in these stories range from very humanized to actually human, and from highly gendered to barely.

Within the context of our discussions about binaries, gender, and sex, I wondered if the illustrations showed the gender or the sex of the characters. With the exception of the autobiographical Persepolis in which the author, Marjane, draws herself, the characters are not real people. They do not have their own expressed identity; they are being created and portrayed for others to look at. The author decides the sex of the characters much like we are assigned a sex at birth. Then, the character is drawn based on their sex and society’s stereotype of their sex, to a certain level. That level is the extent to which the characters are gendered.

I had the opportunity to portray myself, as Marjane Satrapi did in Persepolis, in our anti-self-portrait project. My work did not show a physical body, human or otherwise. I drew an abstracted shield composed of words. There was no identification of my sex in my drawing. However, some of my gender could have come across in the sentences I wrote. Some of those sentences were talking about gendered things, like makeup, clothes and hair. I did not want the internal monologue that I wrote down to be accessible, so I only showed a small fraction of the words. I did not set out to include my gender in my portrait, but it is possible that people may have seen something gendered there. My anti-self-portrait was not, however, an illustration of my physical self, as are the book illustrations.

I see Amelia Bedelia as the most gendered book out of the six, because I cannot ignore the sexist portrayal of Amelia. Amelia is a maid who always takes the housework for the housework literally and messes up. (For example, she separates eggs by putting them far away from each other in the kitchen.) When her employers, Mr. and Mrs. Rogers, come home at the end of each story and get upset, she appeases them with a delicious pie. She is silly and cannot do anything right, but she is miraculously a great cook. In the illustrations, Amelia wears a flowered bonnet, a dress, an apron, and heels. Mrs. Rogers and Great Aunt Myra also wear dresses, heels, and necklaces, and there are flowers somewhere in their outfits. Mr. Rogers wears a suit and has a mustache.

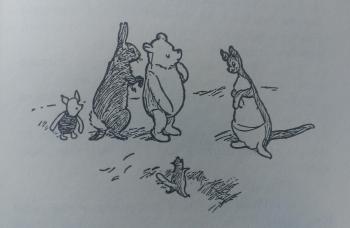

The illustrations in Winnie-the-Pooh are not gendered. The animals are not humanized other than being bipedal. They do not have clothing or hair, so there is nothing (except that Kanga has a pouch, so she must be a female kangaroo) to indicate sex except for pronouns in the story. Christopher Robin, a young boy, does not have the usual short constricted male haircut, but rather a more free, wavy style. He wears a hat, which seemed to be a feminine accessory in other books, and has feminine shoes. He has a teddy bear, but also a toy gun. Although Winnie-the-Pooh is sometimes criticized for having an all-male cast except for Kanga, a mother, the characters are not gendered or stereotyped in their illustrations. They simply have assigned sexes in the narration.

The characters in Berenstain Bears wear human clothes and accessories, but all of their faces and head hair are drawn the same way, with bear snouts and one “hairstyle” that is an extension of the rest of the fur. Their hands and feet have claws and fur. They are drawn as bipedal cartoon bears in human clothing. The gendering is performed solely by clothing and accessories. The mother, aunt, grandmother, and “Sitter” (female baby sitter) all wear dresses and, except for the aunt, some kind of hat. The daughter wears pink overalls and a pink bow. I think that in these illustrations, the hats/bow replace hair as a feminine symbol. When the brother and sister have a bath, the sister still wears the pink bow, and that is the only difference in the way the siblings are drawn. The father, brother, and uncle wear shirts with collars and pants or overalls. The adult clothes are more gendered than the children’s. There are no adult females in pants, and conversely no children in skirts. There are two children irrelevant to the story in the background of one page that I am not able to identify as either sex, because they are not wearing strictly gendered clothes.

The characters in Berenstain Bears wear human clothes and accessories, but all of their faces and head hair are drawn the same way, with bear snouts and one “hairstyle” that is an extension of the rest of the fur. Their hands and feet have claws and fur. They are drawn as bipedal cartoon bears in human clothing. The gendering is performed solely by clothing and accessories. The mother, aunt, grandmother, and “Sitter” (female baby sitter) all wear dresses and, except for the aunt, some kind of hat. The daughter wears pink overalls and a pink bow. I think that in these illustrations, the hats/bow replace hair as a feminine symbol. When the brother and sister have a bath, the sister still wears the pink bow, and that is the only difference in the way the siblings are drawn. The father, brother, and uncle wear shirts with collars and pants or overalls. The adult clothes are more gendered than the children’s. There are no adult females in pants, and conversely no children in skirts. There are two children irrelevant to the story in the background of one page that I am not able to identify as either sex, because they are not wearing strictly gendered clothes.

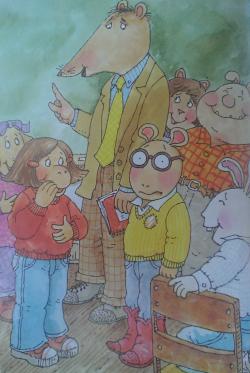

Arthur had the most humanized animal characters out of the anthropomorphic books. They wear clothes and shoes, and they have human hairstyles. The hairstyle makes the biggest impact in distinguishing the sexes. There are many female characters with long hair wearing pants. The male characters either have no drawn hair, or a very small amount of short hair, and the females have styled long hair with animal ears poking through. Unlike in Berenstain Bears, the grandmother and DW are the only main female characters wearing dresses. Arthur’s female friends usually have a pink sweater or accessory but they wear pants. Arthur and other male characters, his teacher, his friends, and his father, always have collared shirts.

Arthur had the most humanized animal characters out of the anthropomorphic books. They wear clothes and shoes, and they have human hairstyles. The hairstyle makes the biggest impact in distinguishing the sexes. There are many female characters with long hair wearing pants. The male characters either have no drawn hair, or a very small amount of short hair, and the females have styled long hair with animal ears poking through. Unlike in Berenstain Bears, the grandmother and DW are the only main female characters wearing dresses. Arthur’s female friends usually have a pink sweater or accessory but they wear pants. Arthur and other male characters, his teacher, his friends, and his father, always have collared shirts.

The sex of the dogs in Clifford was differentiated only by the presence of eyelashes on the female dogs. I expected eyelashes to be drawn in on females in other books, but they were not present in any of the other illustrations, except an occasional sighting in Persepolis. The few human characters in Clifford follow the long hair females rule, and there are a few children wearing pants rather than skirts. In Clifford, Berenstain Bears, and Arthur, the female children do not always wear skirts or dresses.

The sex of the dogs in Clifford was differentiated only by the presence of eyelashes on the female dogs. I expected eyelashes to be drawn in on females in other books, but they were not present in any of the other illustrations, except an occasional sighting in Persepolis. The few human characters in Clifford follow the long hair females rule, and there are a few children wearing pants rather than skirts. In Clifford, Berenstain Bears, and Arthur, the female children do not always wear skirts or dresses.

Lastly, I looked again at the first chapter of Persepolis, containing the illustration that made me think about gender in illustrations. As in Arthur and Berenstain Bears, and like Mr. Rogers in Amelia Bedelia, the male characters have shirts with collars. They also have short hair and either a beard or a mustache. The female characters have longer hair and usually show bangs. The school children wear pants, like in Arthur, but in this case, it is because of the rules about not exposing their skin. Because of these rules, the sex of the characters is mainly shown by their clothes, especially the veil. However, in the image of eight children without veils, I distinguished the boys from girls by their hair and shirts.

In all of the books except Winnie-the-Pooh, I categorized the characters into male and female by their clothing and/or hair. In Arthur, hair was the most significant factor, in Berenstain Bears, clothing was the only clue, and in Clifford, only eyelashes separated the female and male dogs. But in Winnie-the-Pooh, I did not find any gendered characteristics on the animals, and I read for pronouns to find out the sex of the characters. Going through the drawings in these books to label the physical features and male or female made me feel guilty, like I was excessively stereotyping. Even some characters in the background illustrations who were not part of the story were easy to categorize based on their hair.

I was almost disappointed that there was not some secret other element to determining the sex of the characters. In real life, however, when we see a baby, we only know the sex based on the color and style of the clothes they are wearing. Children have hairstyles “appropriate” to their sex and they continue to wear gendered clothes. Illustrators gender the characters just like parents gender their babies and toddlers according to the social binary. Once we are old enough to decide our own clothing and hair styles, we will usually keep following the rules. And if we do not, then people will judge us and sometimes mistake us for a different gender than the one we are trying to portray.

My automatic association of long hair and certain clothes with female made me wonder when those “rules” were put in place, and how children learn them. I found two books on the subject that both had “pink” and “blue” in the titles: Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America by Jo B. Paoletti, and Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow into Troublesome Gaps—and What We Can Do About It by Lise Eliot, as well as the article “Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair” by Anthony Synnott.

Before the twentieth century, babies were dressed in white clothing that did not vary by gender (Paoletti, 85). People started dressing their babies in gendered clothes due to an evolution of clothing styles and production methods. Companies sold gendered clothes so that they could not be handed down to a sibling of a different sex. We know the sex of a baby before it is born, and we use that information to purchase furniture and clothes and choose a name for the baby (Paoletti, 60).

Babies learn about gender based on what they see and how they are treated, similar to the way they learn language: immersion (Eliot, 8). For babies, their clothing “shapes the response of others,” and that response helps them to learn about gender (Paoletti, 13). Children will be able to correctly identify male versus female by the time they are three years old (Eliot, 115). A few years later, they will start to avoid objects that are the “wrong gender” and “enforce” gender stereotypes in their peers (Eliot, 116-17). I think that children’s books are part of the immersion of gender stereotypes that children learn from, but also a way for them to practice identifying genders.

As for hair, it is possible that the binary of long hair for females and short for males came from the bible, which says in 1 Corinthians 11:14-15 that for a man to have long hair is shameful, but for women, “it is a glory to her” (Synnott, 381). Very old stories such as Rapunzel also demonstrate “the appeal of long hair” for women (Synnott, 384). Facial hair, too, follows the rule that “opposite sexes have opposite hair” (Synnott 382). Many adult men in the children’s books had mustaches, and none had long hair. The long hair-short hair binary was the most strictly adhered to rule in the illustrations, if hair was drawn in.

While gendered clothes for babies are relatively new, gendered hairstyles and gendered clothes for adults have been around for many centuries. We start to learn the “rules” of what female and male look like from the moment we are born and put into a pink or blue blanket, and then we can practice applying those rules when we choose toys and clothes. Children’s book illustrations are a tool for putting the idea of “she” and “he” together with a particular image as children are growing up. Even when characters in the books are not human, they still follow the rules, except with the Winnie-the-Pooh drawings. Although the portrayal of Kanga as solely a mother is sexist, the illustrations of all of the characters do not fall into the trap that the other books did, and I was impressed by the gender neutrality.

I found the different ways that the children’s book illustrations utilized human characteristics to gender their characters very interesting. Looking through the drawings made me think about if I make the same quick judgments when I see new people in the world. We use our physical appearances to show our own identities, and we learn, as we grow older, what constitutes those identities from the world around us. Agency in deciding our own clothing and hairstyle is very important, because those styles determine how everyone views us when we are the illustration that everyone is looking at.

Works Cited

Berenstain, Stan, and Jan Berenstain. The Berenstain Bears and the Sitter. New York: Random House, 1981. Print.

Bridwell, Norman. Clifford's Family. New York: Scholastic, 1984. Print.

Brown, Marc. Arthur Writes a Story. Boston: Little Brown, 1996. Print.

Eliot, Lise. Introduction. Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow into Troublesome Gaps--and What We Can Do About It. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. 1-18. Print.

Eliot, Lise. "Learning Through Play in the Preschool Years." Pink Brain, Blue Brain: How Small Differences Grow into Troublesome Gaps--and What We Can Do About It. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009. 103-42. Print.

Milne, A. A., and Ernest H. Shepard. Winnie-the-Pooh. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1988. Print.

Paoletti, Jo B. Pink and Blue: Telling the Boys from the Girls in America. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2012. Print.

Parish, Peggy, and Fritz Siebel. Thank You, Amelia Bedelia. New York: Harper & Row, 1993. Print.

Satrapi, Marjane. "The Veil." The Complete Persepolis. New York: Pantheon, 2003. 3-9. Print.

Synnott, Anthony. "Shame and Glory: A Sociology of Hair." The British Journal of Sociology 38.3 (1987): 381-413. JSTOR. Web. 3 Oct. 2013.

Comments

illustrating gender

Polly—

You’ve assembled quite the interesting line-up of stereotypical gender representations; it’s intriguing to see you lay them out in this way. You’re very even-handed in your treatment of the material—you describe what you see, and say that these books “are part of the immersion of gender stereotypes that children learn from, but also a way for them to practice identifying genders.” What I can’t tell is whether you think this process is good, bad or indifferent.

It’s also intriguing to realize that we may not all read these images the same way. While you were “impressed by the gender neutrality” of Winne-the-Pooh, Celeste sees “Winnie as an effeminate male character”--but is unsure why.

It’s often happened that students realize in my classes that what they were taught as children did not serve them well, and sometimes they try their hands at creating alternative stories for children. You might want to check out several examples of these, which are all available on-line. Only the first two are aimed @ questions of gender differentiation; the third is an eco-story, and the last two evolutionary ones. But you’ll get my drift--my question is basically the same as EmmaBE’s: “do you think there will ever be a children's book that can portray a character that does not represent traditional gender expression?... without their storyline revolving around this trait?” Do you think the creation of such a book is desirable?

The Story of an X

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Thoreau Children's Story

My Great Granddaddy was a Monkey

Story for Children

A lot of these books have

A lot of these books have characters gendered by appearances because they are picture books. In my essay, I thought a little about mimesis in The Doll's House. I considered the possibility that because it was a graphic novel, it was less mimetic than a novel because communication with images and words is a way to break down the process of patriarchal signification. However, you seem to have found the opposite. Interesting how a similar medium can produce opposite interpretations and experiences.

Additionally, I'm just curious - do you think there will ever be a children's book that can portray a character that does not represent traditional gender expression? (Bonus: do you think that this book will be able to have such a character without their storyline revolving around this trait?)

Fascinating! On a base level,

Fascinating! On a base level, I was most intrigued by your idea that animals seem to almost escape being gender qualified by their 'societies'. I never thought of Winnie the Pooh as gendered, quite unlike a book like Amelia Bedelia. Looking back, I see Winnie as an effeminate male character--but I wonder why. Looking forward to parsing this out.