Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

EvoLit Final Web Event: Pestilence

Pestilence

(bubonic plague under a microscope)

1. The Rake

“He had a powerful, rather emotional delivery, which carried to a great distance, and when he launched at the congregation his opening phrase in clear, emphatic tones: “Calamity has come upon you, my brethren, and, my brethren, you deserved it,” there was a flutter that extended to the crowd massed in the rain outside the porch.” (94)

Sebastien was not a religious man. On the contrary, though his uncle was the Jesuit priest Panneloux, Sebastien lacked any sort of religious fervor. He lied with impunity, stole, drank til he was sick, and romanced numerous women. His parents might have been horrified by his behavior, but chose to look the other way; Panneloux, the town's religious authority, was far too busy preaching to the townspeople about impending doom and the consequences of their actions. Plenty of his neighbors took issue with his libertine behavior, but Sebastien lived a fully enjoyable life, and to his way of thinking, anyone who disagreed with him could be damned.

Then, of course, the plague descended. In weeks, the bright, familiar town had become a dark place, fear and sorrow etched upon every face. At first nothing changed for Sebastien. Fortunate as he was to live in a wealthy quarter of town, he was able to continue gambling, drinking, and making merry as usual. But as time wore on, the dreaded disease penetrated even the richest of homes, bringing senseless death and grief to everyone in its path. Sebastien's friends were less and less able to spend time with him. His gambling partners disappeared from the tables, one by one, as they found more important duties to attend to with their grieving families. Even Sebastien's love life suffered. His female companions no longer had time with him. Sebastien found that it became very difficult to enjoy himself when his usual companions were all either dead or mourning.

His parents, too, became more tiresome. They began requiring him to attend regular mass with them in an effort to save his soul, and with no other social engagements he had no way to refuse them. Sebastien thought he might rather die than listen to his uncle's sermons; they all centered around guilt and consequences - very boring topics. Even as the death toll mounted, Panneloux's sermons drew reliably huge crowds of those who wished to save themselves or their families from the plague. Sebastien's uncle was a proud man, and he made the most of his audience. Each sermon contained more fire and brimstone. Normally these speeches had no effect on Sebastien, who had perfected the art of sleeping without appearing to do so.

One Sunday, however, Sebastien was in a terrible mood. One of his dearest friends, Armand, had passed away the night before, and Sebastien had not yet had time to fully comprehend the loss. Usually Panneloux's sermon began with a prayer and the invocation of God's name. But something was different today: rather than merely quoting scripture, Panneloux changed tack. He strode up to the pulpit, his eyes glittering with emotion. "Calamity has come on you, my brethren, and, my brethren, you deserved it," he said simply. He was silent for a moment, as a wave of dismayed muttering rippled through the crowd. Sebastien jerked forward in his seat. He had never heard his uncle say such a thing, whether at the pulpit or at the family table. What could this possibly mean?

The next few hours were the worst of Sebastien's life. Panneloux laid the blame for the plague on the shoulders of the sinners in his pews; by turns he roared and whispered of their guilt. Sebastien had never heard his uncle speak so powerfully, nor had he ever before been so affected by a sermon. Panneloux seemed to stare at Sebastien, seemed to blame him in particular. With each word, Sebastien shrank further and further into his seat. Was this plague truly God's punishment for Oran's deceit? Were all of these townspeople, all of those who looked down on Sebastien for his misbehavior, truly guilty themselves? Then another, more frightening thought struck him: if these seemingly good people had done enough evil to deserve the plague, then what about those who were not so good? Armand had been a roustabout, and now he was dead, after an especially painful case of the plague. What worse punishment awaited Sebastien, who was unrepentant?

At the end of the sermon, Panneloux seemed exhausted. He had a wild look in his eyes, spittle clinging to his lips, and he leaned against the pulpit as if to remain standing. The congregation, meanwhile, did not move for several moments, shocked as they were. When Sebastien finally rose from his seat, he left the church at speed, choosing to walk home alone. He did not know how to sort out his thoughts. Was everyone in Oran guilty? Or could his lifestyle, and that of his friends, truly be the cause of the plague? What sort of god would punish an entire town for the crimes of a few? Yet Sebastien was familiar with the wrathful, vindictive, jealous God his uncle presented. How could Oran ever make amends to such a god?

How could he ever make amends?

Sebastien's feet turned him toward the center of town, toward the home of one of the town doctors, Rieux. At Rieux's doorstep, Sebastien hesitated. Perhaps he was mistaken, and all the guilt knotting his innards was nothing more than superstitious worry. Perhaps this would do no good, whether or not God cared about human behavior. But doing something was better than doing nothing. Resolved, Sebastien swallowed hard and climbed Rieux's stairs. He knocked lightly and held his breath as the door swung open.

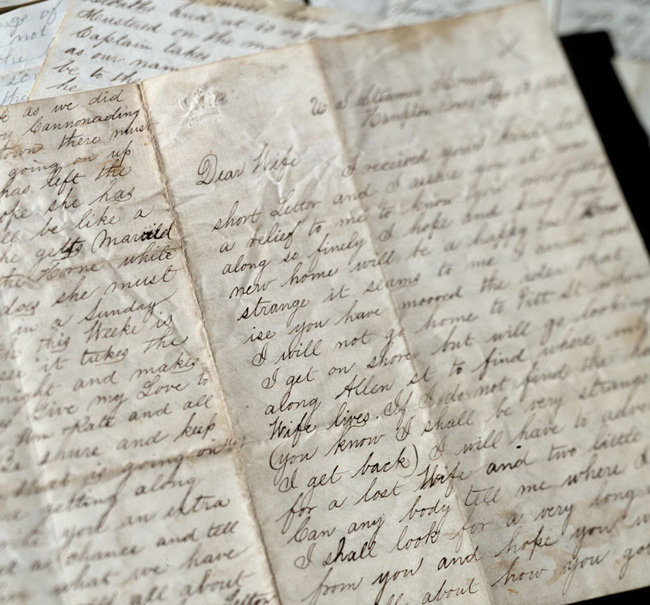

2. The Letter

“…There was nothing shameful in preferring happiness.

'Certainly,' Rambert replied. 'But it may be shameful to be happy by oneself.'” (209)

Dear Adele,

I know that my decision to leave will seem curious to you. It is certainly one that has troubled me greatly to make and I have not done so lightly. I have nursed Mother and Father to the best of my ability, but God has seen fit to take them both. This accursed plague has destroyed our family and now you and I are the only ones left. Even now, I pray that you will not fall prey to Oran's scourge, that you will display the same resistance to this disease that I possess. I will attempt to send this letter to you through a trusted friend; surely if he can smuggle me from the city, he can ensure that this letter will reach your hands.

My purpose in writing to you is to explain my decision. Choosing to leave Oran has been agonizing, but I felt it was the best thing to do. Caring for first my aged mother, and then my father, has taught me a great deal about myself. I know my own limits, cousin, and after watching my beloved parents suffer as they did, I know that I would rather die by my own hand than to fall ill to the plague. I do not know why I have been spared for so long, but I have no faith in Luck or Fate any longer. I confess I was preparing myself to end my life when a friend, whose name I shall not disclose, contacted me about his plans to flee the city. He offered me the chance to go with him, and though it hurt me to consider leaving my home at first, I feel as if God Himself has arranged the entire thing.

I leave tomorrow at first light. By the time you receive this letter—if indeed you receive it at all—I shall be gone. I ask that you find a way to forgive me for what you must perceive as a betrayal. I do not intend to return to Oran – all of my parents' possessions are yours, as is our home. You will be in my prayers, Adele.

May God keep you safe always.

Your cousin,

Henri

3. Compassion

“…when a man has had only four hours' sleep, he isn't sentimental. He sees things as they are; that is to say, he sees them in the garish light of justice – hideous, witless justice. And those others, the men and women under sentence to death, shared his bleak enlightenment.” (193)

The two had been married for over fifty years, yet they seemed never to tire of one another. Young couples who lived nearby hoped to be like to the Duponts when they were old and gray. Over the years, the Duponts had survived the deaths of two of their four children and the loss of many friends to old age. Together, they said, they could do anything. And indeed, for two people of such advanced age they were in very good health. They took long walks through town every morning and cooked meals for friends and neighbors every evening. They were generous of spirit and gladly shared their time, money, and home with others. They enjoyed companionship and told wonderful stories of their younger days; the entire neighborhood knew and loved them.

The plague, when it reached their district of Oran, did not discriminate. The young, the old, the healthy, the infirm, all appeared equally likely to succumb to the disease. The fear began to grow out of control as the bodies piled up at every other corner; families in the neighborhood huddled inside their homes, too afraid to venture out. But then, a few weeks after the first outbreak, the Duponts left their home and went on their usual stroll through the streets. This time, however, both Monsieur and Madame Dupont carried a basket. They stopped at each home, leaving food for the parents, a toy or a book for the children, and a kind word for the whole family before moving on.

This continued for over a month; despite severe rationing, the Duponts made a point to visit each of their friends and share what little they had. One young man asked them why they did so, when almost every household but theirs had been struck by the plague. Simply put, they said, they had lived long, wonderful lives, and the bounties they had been given were meant to be shared. They did not ask for thanks or acknowledgment; they needed nothing in return for their kindness. When a house was about to be quarantined, the couple would go to hold the hands of the dying person and give them some words of comfort.

Miraculously, the Duponts themselves seemed to display no signs of the plague themselves. But then one day, they did not make their expected rounds. When the sun began to set the next day, and still no one had seen or heard from them, a few of the healthier neighbors wondered privately whether someone ought to check on them. It was several more days, however, before a group of neighbors worked up the courage to check on the elderly couple. They knocked timidly at the Duponts' door, assuring one another that the two were merely resting from all their efforts. But sweet Monsieur Dupont did not come to the door, and the neighbors could not hear Madame Dupont warm laughter; when they pushed the door open, the neighbors found the Duponts in their bed. They lay in each others' arms, the buboes of the plague raised on their skin, quite peacefully dead.

4. The Opera

“For at the same moment the orchestra stopped playing, the audience rose and began to leave the auditorium, slowly and silently at first … women lifting their skirts and moving with bowed heads, men steering the ladies by the elbow to prevent their brushing against the tip-up seats at the ends of the rows. But gradually their movements quickened, whispers rose to exclamations, and finally the crowd stampeded toward the exits, wedged together in the bottlenecks, and pouring out in the street in a confused mass, with shrill cries of dismay.” (page 201)

Amelie had been dressed for nearly an hour. She sat on the chaise in her best evening gown, tapping her ivory-handled fan impatiently against her palm. Where was her husband? Ever since the damned plague had descended upon the town, nearly all of Amelie's usual diversions had vanished. Now, visiting the opera house every Friday evening was the highlight of Amelie's week.

But where was Louis? He had gone out much earlier to procure rations for the week, and if he did not return soon they would be late for the opera, or worse, miss it altogether. At long last, Amelie heard the front door open, and she rose eagerly from her seat. “Louis!” she called. “Hurry and dress! We mustn't be late!” There was no reply, though Amelie could hear her husband in the kitchen, putting supplies away.

She entered the kitchen, lifting her long skirt as she walked. “Louis?” He stood beside the sink, carefully organizing the rations on the counter. He smiled wanly as she came to stand beside him, and Amelie was struck by how tired he looked. There were dark circles beneath his eyes and his broad shoulders drooped downwards, as though they bore a heavy burden.

“Must we, Amelie? The theater has played Orpheus for a month and a half now.”

Amelie placed a gloved hand on his arm. “Oh, please! It's so diverting, and it's vastly preferable to crouching at home, brooding.”

He sighed heavily, pushing the empty bags aside on the counter. “The Richelieu family is dead. Pierre told me. Apparently once their daughter fell ill, it was only a matter of days before the rest of the family was claimed.”

A thickness formed in Amelie's throat. “How terrible,” she murmured. Three children and their parents, friends of hers. She felt momentarily faint. “And – and the funeral?”

Louis shook his head. “That quarter of the town was locked down. Pierre had just left when the quarantine was announced. It's not long before we're all forced to stay in our houses and wait to die, like the damned rats.”

Bile rose in Amelie's throat. “Louis, I don't want to speak about this anymore. I–”

“Let's leave,” Louis interrupted urgently, seizing Amelie's shoulders. “Pierre said he has connections with guards. We have money, we may be able to pay someone to let us through.”

“But Oran is our home. We grew up here,” said Amelie, stunned. The idea of leaving had never occurred to her, although of course she had heard that people had tried. “But – surely things aren't so bad yet.”

Louis scoffed and pulled away. “Amelie, the daily death toll is in the hundreds already! How much worse must it be for you to realize? We could die, Amelie! It's only by the grace of God we haven't yet.”

Blinking away tears, Amelie said, “Louis, please, let's – let's not think about it now.” His face changed, and his expression, a combination of anger and fear, worried her more than his words. “Later we'll discuss it, I promise,” she said desperately. “Later. But right now I – I can't think about it.”

Louis hugged her gently. “Very well,” he said. “Orpheus again, eh?”

The opera house was as lovely and welcoming as ever. Its plush seats, vaulted ceilings, and warm lighting never failed to transport Amelie. Within the walls of the theater, the plague was but a dark thought, easily pushed to the back of her mind. Amelie settled down in her seat, her hand in Louis'. She looked around at the other couples filing in, slowly filling the rows. The crowd seemed a bit thinner this week, and Amelie's mind drifted to the Richelieus, and then to other faces she knew she'd never see again – the Moreaus, the Fourniers, the Lefevres. All lost to the plague. A strange sensation rose within her, a mixture of panic and foreboding. Amelie squeezed Louis' hand, and he looked at her with concern. “Amelie?”

“I'm fine,” she said, and carefully pushed her troubling thoughts aside. Soon enough the lights were extinguished and the opera began. The swelling music, the voices trembling with vibrato, the emotional tale – Amelie was utterly captivated. Perhaps she had heard the music so many times she would soon have the entire opera memorized; perhaps the costumes looked a bit worn; perhaps the actors looked a bit pale and tired. But Amelie didn't care. She easily ignored all this and lost herself in the spectacle.

By the third act, Amelie had to admit that she was slightly taken aback by the clumsiness of the lead actor. Tonight, Orpheus had added into his performance strange, jerky gestures, so small that unless one was very familiar with the show, as Amelie was, they would have been undetectable. Amelie frowned, but her anticipation of Orpheus' duet with Eurydice made it impossible for her to worry about such a trivial matter. In the middle of the duet, however, the actor stumbled, and then walked unsteadily toward the footlights. For a moment Amelie was put out; he was ruining the emotional affect of the song. But then suddenly he collapsed, and as he convulsed violently on the stage it became very clear that this was not part of his theatrical performance.

Amelie, who had been sitting forward in her seat, reeled backward, horrified. The theater was the one place where she did not have to think about the plague, where it ceased to exist for a few blissful hours. And now the disease had invaded her last safe place. Louis got quickly to his feet, and reached down to help Amelie to her feet. Stunned as she was, it took some gentle prodding before she rose and walked stiffly into the aisle. A strange calm had fallen over the theater. Some other couples were also exiting, the ladies led by their male companions, but many sat in silence, staring at the twitching, fallen Orpheus. Then whispers and murmurs broke out, and as Louis led her quickly out of the theater Amelie could hear screams of horror behind her, and then a sound like rolling thunder as the audience rushed as one toward the door.

Tears dripped down Amelie's face as she and Louis reached their home. “They will declare a lock-down on our quarter by the morning,” said Louis gravely, helping Amelie up the front steps and ushering her into the house.

Amelie pulled off her gloves and shawl and dropped them on the floor of the front room. She kicked off her shoes, then reached up removed the pins from her hair and let them fall from her hands. A savage anger rose within her and she began tugging roughly on her dress. The buttons were tiny and she didn't have the patience to undo each one. Amelie pulled harder, ripping the fragile material of the dress.

“Amelie.” Louis grabbed her hands. “Don't. You'll rip your dress.”

“I don't care,” she said. “I don't – I can't stay here, Louis. I can't breathe in this godforsaken town. Speak to Pierre. I want to leave.”

“Are you sure?” he asked.

She nodded, looking straight into his eyes. “There's nothing here for us but death.”

Amelie laid her head on Louis' shoulder and wept.

5. Jacques

“Mother and father were standing at the bedside when Rieux entered the room … [the mother] was holding a handkerchief to her mouth, and her big, dilated eyes followed each of the doctor's movements.” (211)

He was only a child.

When the dead rats piled up in the streets, I thought it was merely a strange occurrence. But then townspeople began to die, only a few at first, and then more each day. I began to pray that God would spare our town. I went to Mass every evening, hoping that my attendance would strengthen my pleas. Then the death toll grew even higher, and the dead in the poorest quarters were left in the streets for days until they could be buried. I began holding my own vigils at home, begging God for a cure, for salvation. The plague spread swiftly from the poor areas to the wealthier parts of town, and I kept my children inside. If God wouldn't protect the town, I would protect my children. Jacques and his younger sister Elyse were my entire world.

My husband, the town magistrate, had business in town every day. When he left the house in the morning, I would watch from our front window, unable to move until he was out of sight. Then my prayers began. I muttered prayers under my breath every possible moment. I prayed while I watched my children play, I prayed as I cooked their meals, I prayed when I put them down for their afternoon nap. I prayed as I boiled our soiled clothes, as I scrubbed my floors and walls and tables. When my husband returned at night, I prayed silently as I greeted him. I made him wash thoroughly before he came near the little ones. I took every measure I could think of. I prayed and I was sure that God would hear me. He would spare my family.

Then one day, two months after the beginning of the plague, Jacques was irritable and tired. I decided to give him a bath while his sister slept. As I pulled off his shirt, I saw a lump swelling on his neck. There were more beneath his arms. My breath caught in my throat. I knew that these lumps were the first sign of the plague. But how could this be?

When my husband returned home, he sent immediately for the physician. When Dr. Rieux arrived, my husband led him into our bedroom, where I sat with our son on my lap. Jacques had become feverish, and I cradled him to my chest. My husband said quietly, “Save my son.” Rieux promised to do everything in his power. We nodded and agreed. Rieux turned to me. “You must all be quarantined at the hospital while we treat Jacques.” I stared blankly back at him. “You must be quarantined separately from Jacques, to reduce your risk of contracting the disease,” he said.

Jacques whimpered, and my arms tightened around him. “No.” I couldn't be parted from him. “He needs his mother. He needs me with him.”

Rieux shook his head. “That won't be possible,” he said kindly. “I know how difficult this must be, but – the safest thing for everyone is for you to be separated.”

In the end I let them take him away. I, my husband, and my daughter were all moved to the quarantine hospital. Rieux assured us that Dr. Castel had created a new serum they would administer to Jacques in the auxiliary hospital across town. Their hopes of success were high, he said.

I later found out that receiving the serum did nothing but quicken Jacques' death. While I was locked in quarantine, praying for a miracle, my son screamed and writhed in pain for hours on end before he finally slipped away.

Our family couldn't have a proper service for him, because we weren't allowed out of quarantine. Instead, Rieux said he would send the town priest to visit us. I refused this offer.

The plague ended a few months later. My husband, Elyse and I never contracted the disease. We had a memorial service for Jacques as soon as we were able, but I didn't want to have a church service. Despite all my prayers and pleading, my God had done nothing.

He was only a child.

In writing these vignettes, I realized my journey in exploring The Plague mirrored my journey in the course. The first two vignettes I wrote (as my 3rd web event, which are now the 4th and 5th vignettes in this series) dealt more with my indignation at the lack of strong female characters in the novel – in other words, the historical binary I saw as being upheld in the story. However, as I wrote the other three vignettes, I saw that my current focus, and perhaps more productive one, is about responsibility and agency.

Through my own interpretation, and through course discussions, I have come to understand that the plague in Camus' novel did not represent justice; I think it represented a “great equalizer,” one that forces all faced with it to reevaluate their needs and desires and reduces people to their truest selves. Although the plague appears to remove all choices, I saw Camus' characters as proving that there is always a choice, that we always have agency. With this agency comes the responsibility to accept accountability and to accept the consequences of the decisions we make. In all of the vignettes, the characters make choices, although they may or may not realize that they do so.

In “The Rake,” Sebastien decides that he wants to help Rieux, even though he is still entirely unsure of his own culpability in the onset of the plague. In “The Letter,” Henri makes a decision in his own best interests – apologetically, perhaps, but he commits to his choice. “Compassion,” meanwhile, is about a couple who puts their own interests last. “The Opera” is about a woman choosing to deny the tragedy of her own situation, while “Jacques” concerns a mother who simultaneously accepts blame for her son's death and rejects her faith in her grief.

In order to develop my own understanding of agency, I looked at the OED online and A Feminist Ethic of Risk by Sharon D. Welch. The OED lists six meanings of “agency,” the first of which is the most relevant: “The faculty of an agent or of acting; active working or operation; action, activity.” This faculty has primarily occupied me while writing this web event. Building on this, I looked at Welch's book. “The assumption of 'doing something,' which means controlling events and receiving a quick and predictable response, is both part of the problem and also prevents its resolution,” says Welch, “…we are shaped by an ethic of control – the assumption that effective action is unambiguous, unilateral, and decisive” (24-25). Welch goes on to build an argument for a new brand of social ethics, deploring a “failure of nerve” when we deal with problems: “the inability to persist in resistance when problems are seen in their full magnitude” (40).

I agree with Welch's term “ethic of control,” but I am less concerned with the moral implications of a “failure of nerve.” Certainly a new definition of “doing something,” one which simply means admitting one's ability to make decisions and accepting the responsibility for these decisions, would help in the creation of a new kind of social ethics. However, although I agree with Welch's argument, in this project I chose to focus on the basic issue of agency itself – how each character has the ability to make decisions even when it might appear that he or she does not.

To this end, none of these vignettes represents an ideal, or a moral lesson. Each one, I think, presents a decision which could be seen from many perspectives. For example, the Duponts in “Compassion” could be seen as a morally good couple for trying to bring comfort to the sick. On the other hand, they might have actually endangered others as carriers of the plague. One might view Henri in “The Letter” as making the wrong choice – but one might also argue that, having cared for his sick parents, he deserves the chance to get out of Oran before he falls ill himself.

I'm not as interested in the morality of the choices made; I have focused more on the faculty of the characters in making choices because I think that before we can address the “failure of nerve” Welch discusses, more people must accept responsibility for their choices regardless of moral determinations. I hope that my vignettes successfully portray what I saw as a central message of The Plague: we always have agency; we always have a choice.

Works Cited

Camus, Albert, and Stuart Gilbert. The Plague. New York: Vintage, 1972. Print.

Oxford English Dictionary Online: http://oed.com/

Welch, Sharon D. A Feminist Ethic of Risk. Revised ed. Minneapolis: Fortress, 2000. Print.

Images: Bubonic plague under a microscope:

http://www.ciriscience.org/thumbimage.php?id=132

Letter: http://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/monitor/geer_letter_650.jpg

Compassion: http://www.proteuscoven.org/proteus/selfcare/img_compassion365b.jpg

Opera House: http://randaclay.com/opera2.jpg

Mother and child: http://kethry.files.wordpress.com/2008/02/mother_child_79.jpg?w=329