Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

A response to “Miss Representation 8 min. trailer:” Changing gender stereotypes by increasing visibility of female athletes

The trailer for Miss Representation by filmmaker Jennifer Siebel Newsom describes the power of the media, acknowledging that people learn more from it than any other single source of information. The media is the primary force that shapes our society: “politics, national discourse, and children’s brains, lives, and emotions” (Jim Steyer, CEO, Common Sense Media). Upwards of one billion people use the Internet every day (Marissa Mayer, Vice President, Consumer Products, Google); images are widely available and accessible without restrictions.

The messages disseminated by the mainstream media are pervasive, and more often than not emphasize and perpetuate harmful gender stereotypes. According to Miss Representation, women hold only 3% of clout positions in telecommunications, entertainment, publishing and advertising and comprise just 16% of all writers, directors, producers, cinematographers and editors. Because women are generally not the ones deciding how they are represented in the media, they are often shown as sex objects, valued by their looks rather than their achievements. As a result, “girls are taught that their value is based on how they look, and boys are taught that that’s what’s important about women” (Jean Kilbourne, EdD, Filmmaker, Killing Us Softly).

Jackson Katz, co-founder of the Mentors in Violence Prevention (MVP) Program at Northeastern University’s Center for the Study of Sport in Society, asserted in the film, “We’re socializing boys to believe that being a man means being powerful and in control; being smarter than women, or better than women, or our needs get met first in relationships with women. That’s not genetically predestined. That’s learned behavior.” I participated in the MVP program as a senior at Amherst Regional High School, where I was first introduced to the idea that gender roles are socially constructed. To me, social construction of these stereotypes also represented an opportunity for change, whereas, I concluded, biological bases for sex differences are static; we are bound to our DNA and our hormones, but not to our interpretations and creations of the Self.

Recent scholars, however, have questioned the long-term effects of biology on sex and gender. Rebecca Jordan-Young, in her book “Brain Storm,” acknowledges, “because of early exposure to different sex hormones, males and females have different brains” (1). However, also presents the perspective of evolutionary biologist Richard Lewontin: “a genotype does not specify a unique outcome of development; rather, it specifies a norm of reaction, a pattern of different developmental outcomes in different environments” (272). Furthermore, “there is no environment-neutral way to specify the sex difference” (278). Although we still do not know the extent to which “nature” determines gender and sexuality, the environment – nurture – clearly plays an important role. Thus, people are not biology-bound, but rather shaped and influenced by their environments.

When ideals promoting hyper masculinity and misogyny permeate and even define these environments, people react accordingly. Miss Representation calls for increased representation of women in positions of power in order to counter these harmful stereotypes about women and men. Katie Couric, CBS newsanchor, states in the film, “The media can be an instrument of change. It can maintain the status quo and reflect the views of the society. Or it can awaken people and change minds. It depends on who’s highlighting the plain.” The system that currently exists is a vicious cycle: the lack of women in these roles perpetuates stereotypes, but also discourages girls from attaining the positions. While I thoroughly agree with the views expressed in Miss Representation and acknowledge the need for more women in positions of power and influence, especially in the mainstream media, this also assumes that women have not fallen prey to the same stereotypes that objectify and oppress them.

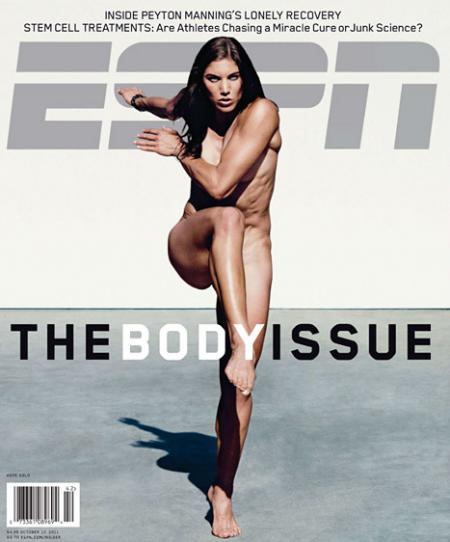

Increased visibility of female athletes in the mainstream media can also contribute to changing the prevailing representation of them as sex objects. These women prove that they are not “bound” to their biology, that women are not naturally weak or stick-thin; they provide alternate images to those presented in the media. Most recently, Hope Solo emerged on the cover of ESPN Magazine’s Body Issue, which is published each year in response to Sports Illustrated’s notorious Swimsuit Issue. In this video filmed of Solo during the photo shoot, she explains, “I don’t take it serious, being a sex symbol - at all. I’m an athlete. That’s all I am.” The comments on this video, however – most too explicit to repeat in this forum - show how far we must go before female athletes will be taken seriously, before they will be revered for their determination, their bodies valued for their strength rather than their “femininity.” Increased funding for girls’ sports, support of programs such as Katz’s Mentors in Violence Prevention, and visibility of female roles models like Hope Solo, will contribute to changing societal stereotypes about gender roles.

Comments

Re-representing

jmorgant—

Some years ago I co-taught a course on “Women, Sport and Film” that was offered collaboratively @ BMC and Smith, and where we explored many of the questions you raise here—so you have in me a very interested viewer-and-reader!

This is my favorite line from your paper: “people are not biology-bound, but rather shaped and influenced by their environments.” This certainly opens up possibilities for change; as John Humbach argues, in his essay "Towards a Natural Justice of Right Relationships" (which we’re reading for this week), “to create populations of individuals who are well adapted to life ... you create ... a given kind of social setting."

I’m thinking that this also forms a link between your last paper, on the history of disability studies, and this one, on the media representation of women. Do you know about Aimee Mullins? She first received worldwide media attention as an athlete; her public version of her career is that her disability has been a benefit--she has several sets of legs, both cosmetic and functional, and is able to choose how tall she wants to be.

So, once you’ve reviewed the problem—not only acknowledging “the need for more women in positions of power and influence, especially in the mainstream media,” but also the need to raise and educate young women not to fall “prey to the same stereotypes that objectify and oppress them”—where this project really needs to go next is into an exploration of how to address the issue (lucky thing that your next paper will be about activism, eh?). Your last line is a list of possible ways to “contribute to changing societal stereotypes about gender roles”—increased funding for girls’ sports, violence prevention programs, and visibility of female role models. Where will you locate your own intervention? And what steps might you take in that location?