Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

"The Ugly Footprint of Africa's Black Gold"

Chris Cleave’s best-selling novel “Little Bee” narrates the entangled lives of two very different women from two very different worlds: one from the safe and peaceful Britain, the other from the oil-torn and secretly brutal Nigeria. Little Bee seeks refuge in Britain after fleeing the violence brewing in her homeland over oil, violence that the government turns a blind eye to. While “Little Bee” is a novel, in a Q&A with Cleave he admits that the story does have a basis in reality, though the details and individuals themselves are fictional. On his website, Cleave invites his readers to “Explore the Issues,” providing links to supplemental material on Nigeria, the oil drilling in the Niger Delta, and refugees and asylum seekers. While the page title is “Explore the Issues,” the URL, in fact, reads “get involved.” It seems that through “Little Bee” Cleave is using a novel, a fictitious voice, to reach out to readers who may not pick up a book on human rights or contemporary global events to inform them of issues that may not directly affect them, but weave into the web of humanity’s entanglement and codependence. What is the relationship between Cleave’s fiction and the reality of the almost 160 million Nigerians and all those connected to them? That is what this essay aims to determine.

The Niger Delta region lies in the delta of the Niger River in the South of Nigeria. The population in this area is high, and most of the inhabitants live in poverty in small villages. The most populous country in Africa and the number one petroleum exporter on the continent, Nigeria survives a history of conquest and military occupation. It became part of the British Empire in 1901, gained independence in 1960, and returned to democracy in 1990 after 33 years of military rule. Petroleum, the driving force of Nigeria’s economy, helped lead to the long years of military rule and unrest in the Niger Delta, the primary oil-producing region in the country. In the 1980s oil production soared, but the majority of the population did not see the affect of the country’s new wealth. The relations between the Nigerian people in the Niger Delta’s oil sector and the oil companies themselves is not one of cooperation, and “vandalism of oil infrastructure, severe ecological damage, and personal security problems… plague [the region]” (3).

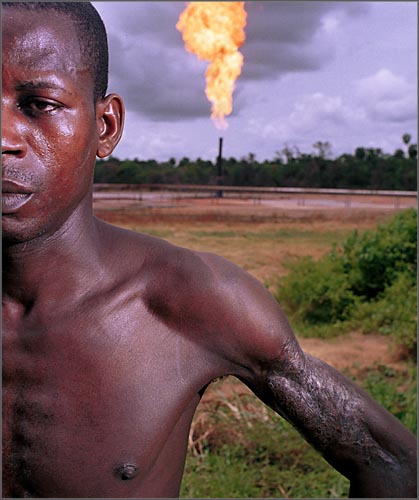

Much of the farming land in this region has been destroyed, with oil leaks contaminating the earth and fresh water supply. While some of these oil spills are caused by damage to oil pipelines by rebel militia, unknown quantities are spilled “from the pipelines which criss-cross Ogoniland (often passing directly through villages) or from blow outs at the wellheads – and gas flaring” (7, page 67), much of which is caused by pipeline and storage facilities that go unmaintained. It is estimated that there are over 300 spills per year in the delta, with Shell accounting for 1.6 million gallons of oil spilled within a ten-year period (7, page 68). In 2009 Amnesty International estimated that at least 9 million barrels of oil have been spilled, and a report in 2006 estimated that 1.5 million tons of oil have been spilled in Nigeria, constituting a human rights crisis (6). Combining these spills and the gas flares that illuminate the sky daily and burn at 14,000°C, “Nigerian natural gas produces 35 million tons of CO2 and 12 million tons of methane, more than the rest of the world” (7, page 68). Not only is this an immense danger to the environment but it also directly affects the livelihood of the farmers in the region who have been displaced and are now unable to work the oil-soaked land.

Because of attacks on the oil infrastructure with acts that include vandalisms, kidnappings, and production site takeovers, oil is not being harvested or exported at as high a rate as it was in the 1980s when the oil industry in Nigeria first took off, feeding the sense of urgency that both the government and the oil companies feel to secure the land and processing facilities in the delta (2). Nigeria is in a precarious position; oil “provides 95% of foreign exchange earnings” and Nigeria’s overreliance on oil places it tenth in the world in oil production and eighth in the world in oil exports (8). Within this ‘oil-complex’ there are more than two groups involved in the struggle over land and oil. In 1994 a mafia of sorts called ‘House of Lords’ (Isongoforo) was created. Community militia were engaging with mobile police and governmental authorities, posing a threat to the oil companies and the general stability of the area; if the area were unstable, oil production was at risk. Isongoforo were hired by the oil companies and paid for protection, and they “occupied the centre of a new governable space which they ruled through force rather than any sense of consent or customary authority… [the] volatile state of affairs collapsed dramatically as local resentments and struggles proliferated” (7, page 64). In 2000 a ‘People’s Revolution’ overthrew the Isongoforo and began to recruit and fund rebel militia groups to “undermine the powers of Isongoforo” (7, page 64). A ‘cultural group’ (Teme) replaced the overthrown Isongoforo and they “instituted a rule of terror and chaos far worse than their predecessors. It too proved unstable in the context of excessive youth mobilization and split into two factions, producing in short order a number of ‘counter coups’ and much bloodshed” (7, page 64). This violence rose to levels that were uncontrollable by government authorities and a web of compliances formed between the competing groups.

A 76-page report was published by an oil watchdog group, Platform, stating that “Shell has fuelled armed conflict in Nigeria by paying hundreds of thousands of dollars to feuding militant groups” (4). This funding encouraged the violence between the groups and lead to the death of villagers and the destruction of villages. As reported in The Guardian, only published in October of this year, “Platform's investigation, which includes testimony from Shell's own managers, also alleges that government forces hired by Shell perpetrated atrocities against local civilians, including unlawful killings and systematic torture.” The report also includes testimony from members of the various militias that were “substantiated” by the unnamed Shell official. WikiLeaks also exposed cables that report Shell officials stating that they had placed staff into “all the main ministries of the Nigerian government, giving it access to politicians' every move in the oil-rich Niger Delta” (5). Through this breach Shell was also able to keep an eye on the known movements of militia groups. Following this leak, the Nigerian government adamantly denied that Shell has any control over the government of Nigeria.

Most days on Yahoo!News the latest diet, the best workout for abs, a football game recap from the night before, a celebrity “who wore it better?” graces the primary news feed. Color photographs are included and the complete lack of correct spelling and grammar are evidence that taking the time to proof-read is a thing of the past. Kim Kardashian’s latest outing is the headline these days. Who really counts? For American media it certainly does not seem that the women and children being killed by militants in Nigeria in a battle over oil fueled by foreign, suit-wearing oil executives count. How many people know about this violence? What can be done for these people, victims of the ubiquity of oil and blood? This is what Cleave is asking his readers. The issues raised in “Little Bee” may not be featured on Yahoo!, may not be on CBS or NBC news; that does not marginalize their existence. Cleave uses his novel as a way to reach out to a broader audience, to instill a sense of urgency within readers for his characters. As the saying goes, “truth is stranger than fiction.” On page 45, Little Bee narrates, “Horror in your country is something you take a good dose of to remind yourself that you are not suffering from it. For me and the girls from my village, horror is a disease and we are sick with it.” Through his novel, Cleave creates a right-relationship between the fiction that is the life of Little Bee and the reality that is so painfully vivid to so many in Nigeria by calling from his readers compassion for one, fictitious, 16-year old Nigerian refugee.

Note:

I feel, ashamedly, like Sarah when I say that I had no idea that these sorts of atrocities were going on in Nigeria, and that it seems like a movie or a bad dream rather than reality. It amazes and saddens me not only that these things are going on, but that I am not being bombarded with them through American media. It is overwhelming how little I feel I could do about this.

I highly suggest reading Watts’s article online. It not only reports facts but addresses the greater social, economic, and human rights issues that accompany the many facets of the history and current events in Nigeria. I also suggest looking through the images in this slideshow that Cleave links to on his website. And I hope that this in some way, however small, increases awareness about life in Nigeria and the Niger Delta.

Works Cited

(1) "2010 Human Rights Report: Nigeria." U.S. Department of State. 08 Apr. 2011. Web. <http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2010/af/154363.htm>.

(2) "Nigeria, the Largest Crude Oil Producer in Africa, Is a Major Source of U.S. Imports - Today in Energy." U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). 13 Sept. 2011. Web. <http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=3050>.

(3) "Nigeria." U.S. Department of State. 20 Oct. 2011. Web. <http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2836.htm>.

(4) Smith, David. "Shell Accused of Fuelling Violence in Nigeria by Paying Rival Militant Gangs | World News | The Guardian." The Guardian. 02 Oct. 2011. Web. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/oct/03/shell-accused-of-fuelling-nigeria-conflict>.

(5) Smith, David. "WikiLeaks Cables: Shell's Grip on Nigerian State Revealed | Business | The Guardian." The Guardian. 08 Dec. 2010. Web. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/dec/08/wikileaks-cables-shell-nigeria-spying>.

(6) Vidal, John. "Nigeria's Agony Dwarfs the Gulf Oil Spill. The US and Europe Ignore It | Environment | The Observer." Latest News, Sport and Comment from the Guardian | The Guardian. 29 May 2010. Web. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2010/may/30/oil-spills-nigeria-niger-delta-shell>.

(7) Watts, Michael. "Resource Curse? Governmentality, Oil and Power in the Niger Delta, Nigeria." Geopolitics 9.1 (2004): 50-80. Taylor and Francis Online. 04 June 2010. Web. <http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14650040412331307832>.

(8) "The World Factbook- Nigeria." Welcome to the CIA Web Site — Central Intelligence Agency. Web. <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ni.html>.

Comments

the reader's right relationship?

rachelr--

as always: your images are compelling. So, too, is your thorough line-up of facts and interpretation--including the report of the oil watchdog group, Platform, that "government forces hired by Shell perpetrated atrocities against local civilians, including unlawful killings and systematic torture." That's the detail that snagged my attention, and the one I can respond to, by not buying gas from Shell anymore....

One spot where we might talk more is @ your ending. You share, on the one hand, your "hope that this in some way, however small, increases awareness about life in Nigeria and the Niger Delta." You ask, on the other hand, "What can be done for these people, victims of the ubiquity of oil and blood? This is what Cleave is asking his readers." So let me ask you, now not only as reader but also researcher: what can be done? What is your right relationship w/ the material you've uncovered?