Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Reality and Virtual Reality?

Reality Check:

The Possible Detection of Simulated Environments

Through Observations of Selected Physical Phenomena

| Originally published in The University of Cape Coast Journal of Philosophy and Culture 3.2 (July 2006), and made available here as a contribution to Serendip's ongoing discussion of science and "reality." Comments welcome in an on-line forum below. A pdf of this paper is available here. |

And yet, and yet… Denying temporal succession, denying the self,

denying the astronomical universe, are apparent desperations and secret

consolations. Our destiny… is not frightful by being unreal; it is frightful

because it is irreversible and iron-clad… The world, unfortunately, is real; I,

unfortunately, am Borges.”

— Jorge Luis Borges, “A New Refutation of Time”

Reality, Virtual Reality, and the Formulation of the Question[1]

This paper attempts to address some specific questions concerning virtual reality or simulated environments of the type discussed in Hilary Putnam’s “Brain in a Vat” scenario and depicted in the popular film “The Matrix.”[2] It does not delve into some of the more complex questions of the nature of knowledge and the role of mind in definitions of “reality” — those topics have been explored at length elsewhere in the philosophical literature. Rather, this paper addresses in simple terms two basic problems. The first: Is there a test we could devise to see if we are living in a simulation of the sort depicted in Putnam’s “Brain in Vat” or “The Matrix”? The second problem, a more difficult one in some respects, is this: What exactly is the difference between that kind of simulation and what we currently believe to be our physical reality?

The film “The Matrix” has been mined almost ad nauseam for its philosophical content, but that does not discount the fact that, for once, a piece of popular culture has made at least some people think about a profound metaphysical question.[3] That question, indeed, concerns the very nature of reality. In actual fact, the first film in “The Matrix” series uses this question primarily as a starting point; the second and third films move away from that, and explore, with mixed success, other philosophical issues. But the basic premise of the original film — the idea that we could all be living in some kind of simulated environment — remains the most intriguing, and I often utilized that aspect of the film when I taught philosophical issues of reality, simulation, and perception in to university undergraduate students.

One of my students once told me that the reason the filmmakers of “The Matrix,” the Wachowski brothers, dropped the initial philosophical issue of reality versus simulation after the first film was that there was “nowhere to go” with it. “Fine, so they are living in a simulation? How much more can you do with that fact?” What the student was saying was true in a sense, but I persisted in using the film as a teaching tool, primarily to explore that basic philosophical question concerning our perceptions of what appears to be a world external to us.

In a methodology that perhaps has become typical in undergraduate philosophy classes, I used to begin my discussion with a reading of Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” then moved on to look at Descartes’ “Evil Genius” scenario, followed by a study of Hilary Putnam’s “Brain in a Vat” question. A viewing of “The Matrix” film came at the end. In this manner, students gained an understanding that this philosophical question of reality versus illusion is an old one. Moreover, they learn that these terms themselves are complex, and that the question even of how to approach this philosophical challenge remains unclear.

My focus in class was always on the same basic question: “How do we know whether or not we are living in a simulated environment of the kind that Putnam describes?” Student discussion tended to circle towards the same general answers, such as: “I know this world around me is real because I can see it, touch it, taste it…” The common rejoinder to that was: “Yes, but that could all be simulated.” Another comment was: “I think that this perceived world is real because it follows consistent physical laws — every time I drop this pen, it falls and hits the desk. If, one day, I dropped the pen and it did not fall, then I might begin to believe that there is something wrong with our reality — that all this is not real after all.”

Theses discussions always tended to grind to a halt, insofar as no one in the class, of course, could prove things one way or another. Certainly, in terms of serious philosophical explorations in epistemology and phenomenology, one could go much further. Moreover, there are also fascinating differences and similarities in Western and Eastern philosophical approaches to the question of reality and illusion, as well as the concept of “life as a dream.” But the essential philosophical question as to how we know what is reality and what is illusion remains problematic, with no resolution in sight. And, indeed, since this class was a morning class, ending about noon, I frequently would joke with the students that even though we might be living in an illusion and my hunger for lunch might be simulated, I was indeed going to respond to that hunger by ending class and getting a sandwich.

After a couple of years of this kind of classroom exposition of this basic question, I began to find that I was satisfied neither in philosophical nor pedagogical terms. The discussions in class had tended to go down the same paths, and while this was fine for the students, whose very learning of this question was sufficient for the purposes of the course — an introduction to philosophy for non-majors — the lack of resolution or the apparent absence of a new approach to the question itself bothered me and some of the more intellectually curious members of the class.

One aspect of the scenario that had come up in the discussion had struck me as important, but it had not been immediately clear for what reason. In Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave,” the prisoners are freed by an outside figure; so, that leads to the question frequently asked by students, “How did that outside person ever become free?” Is there a way for a prisoner to realize on his own that he is living in a world of shadows, and so then free himself? “The Matrix” film addresses this question, but in a rather breezy way, implying that, yes, there was someone who “woke up” through their own realization and volition. Neo, the main character in the film, doesn’t quite do that — he is awakened by the external figure of Morpheus. But Neo is portrayed as always having been a bit suspicious about the so-called “real world” of his boring office job and tiny apartment. But on what evidence had he developed his suspicions? As I always had emphasized to my students, one should operate from evidence, and there seems to be no evidence that our world is a simulation or otherwise.

As implied earlier, of course, the philosophical question of “reality versus illusion” brings up a whole host of other issues. One such issue is that of definitions: What do we mean by “real”? Another issue concerns location: Is there a material world outside of our physical bodies, or does everything reside in the brain? Moreover, there is the question of physical reality itself: If there is a physical, material world, what is its basic constitution? Is there such a thing as “matter”? These and other related issues are ones that I hope to examine in a subsequent paper; here, I would like to deal with the specific question of a physical reality as we apparently perceive it every day versus an illusion akin to the type that Putnam describes. To put it precisely, the question I wish to ask is this: “Is there a test we could devise to see if we are living inside a simulation of the sort described in Putnam’s “Brain in Vat” or the kind shown in the ‘The Matrix’?”

The philosopher Nick Bostrom addressed a related question in his discussion of simulated environments. He approached the matter through a study of probabilities and logical extrapolation.[4] His conclusion was that one might conjecture that we are living in a simulation right now, a simulation that is being run by our distant descendents. But of course, Bostrom offers no proof offered other than what he sees as a high probability that these descendents could build such a simulation.

The general popular answers given to the question of how to determine if we are living in a simulation are few. First, some claim that an occurrence of events with excessive coincidence, defying the laws of chance, might be an indication that the world we are living in is not “real” in some way. A series of highly unlikely coincidences, in other words, might reveal that we are in a simulation that is being actively manipulated by outside forces, or that we are in a simulation that has developed some “glitch” in its operating system. In a similar manner, some would argue that a clear violation of a physical law that we are used to observing, such as the law of gravity, would indicate, again, an intervention in or manipulation of the simulated system, or a technical problem in that system.

But these are not actually tests of what we might call our “perceived reality”; they do not provide a grounds for determining whether what we perceive is indeed a physical world external to us or an artificially-generated illusion. True, the witnessing of a series of unreasonable coincidences or the observation of a sudden violation of physical laws would be grounds for skepticism.[5] And, as Bostrom describes, a civilization might one day be able to build a device that could generate an artificial perceived reality, so that the simulation would provide what we would label as consistent physical or sensory experiences. However, these are all conjectures; what is needed is an actual method for the physical detection of a simulation — from the inside of that simulation.

The “Brain a Vat” Scenario

Before we look at a possible approach, we need a precise definition of problem again: Are we living in a “directly-inputted” simulation of the kind discussed in Putnam’s “Brain in a Vat” scenario or “The Matrix,” rather than as physical beings in a physical universe? A key issue in addressing this question concerns the interface. In a very simple way, we can say that as physical beings in a physical or material reality, our interface with that reality is via our senses. In this description, there is the “outside world” of streets, buildings, trees, grass, other people, and so on, and we receive information about these things through the senses of sight, sound, etc. The interface, then, is the sensory “layer,” where information, such as light waves hitting the retina or sound waves hitting the eardrum, is converted to electrical signals that are transmitted to the brain. This is a model that has been questioned by some scientists, but will suffice for our purposes here.[6]

In contrast to this model, Putnam offers a scenario where electrical impulses go from a simulation-generating computer directly into a disembodied brain:

[I]magine that a human being (you can imagine this to be yourself) has been subjected to an operation by an evil scientist. The person’s brain (your brain) has been removed from the body and placed in a vat of nutrients which keeps the brain alive. The nerve endings have been connected to a super-scientific computer which causes the person whose brain it is to have the illusion that everything is perfectly normal. There seem to be people, objects, the sky, etc.; but really, all the person (you) is experiencing is the result of electronic impulses travelling from the computer to the nerve endings. The computer is so clever that if the person tries to raise his hand, the feedback from the computer will cause him to ‘see’ and ‘feel’ the hand being raised. Moreover, by varying the program, the evil scientist can cause the victim to ‘experience’ (or hallucinate) any situation or environment the evil scientist wishes. He can also obliterate the memory of the brain operation, so that the victim will seem to himself to have always been in this environment. It can even seem to the victim that he is sitting and reading these very words about the amusing but quite absurd supposition that there is an evil scientist who removes people’s brains from their bodies and places them in a vat of nutrients which keep the brains alive. The nerve endings are supposed to be connected to a super-scientific computer which causes the person whose brain it is to have the illusion that... [7]

In Putnam’s setup, the brain can not tell the difference between that interface — i.e., the point where the wires connect to the brain tissue — and an interface involving actual sensory organs, described above.[8] A “brain in a vat” is quite different from a brain in a physical body equipped with sense organs. However, on the face of it, there indeed seems to be no way that a disembodied brain could tell that the world it was perceiving was simulated and that the sense organs had been bypassed. Putnam adds:

When this sort of possibility is mentioned in a lecture on the Theory of Knowledge, the purpose, of course, is to raise the classical problem of scepticism with respect to the external world in a modern way. (How do you know you aren’t in this predicament?) But this predicament is also a useful device for raising issues about the mind/world relationship.[9]

He goes on to examine the “brain in a vat” problem in terms of language, but in some senses this sidesteps the tangibility of the scenario.[10] That is, our current technology is sufficiently advanced to consider the viability of virtual reality of an increasingly sophisticated sort at some point in the future.

Let us return to the basic problem that Putnam outlines; it is very hard to attack head-on, since a disembodied brain is unable to apply any clear kind of test on the information that it is receiving as input. The conscious part of the brain will not suspect that there is anything out of the ordinary, as long as what it receives continues to be consistent with its prior “embodied” experience. One can engage in philosophical debates about this scenario, and Putnam set the modern debates on the issue in motion with the claim in his book Reason, Truth and History that we are not “brains in a vat.”[11] Since then, the debates have continued, but again, without deeply investigating the issue of what kind of determinative test might be applied to the experience that the brain was having.

Again, if the hypothetical simulation were running properly, the “brain in a vat” would have a consistent, even banal experience. There would be nothing to make the brain “question” whether it was disembodied or not. This makes the problem of a test rather challenging. Therefore, it seems best to look at this problem through the use of an analogy, one that also involves perception and simulation, and that utilizes an interface. In fact, it is the interface that will allow us to establish a testing framework.

Building an Analogical Model

Of course, we are not able to actually carry out Putnam’s scenario. That kind of interface is, at present, impossible to construct — and perhaps that is fortunate! However, what is needed is an analogical scenario, one where the subject would have consistent, unremarkable everyday perceptions through regular input of information.

The mechanism of television provides such an analogy. A television screen provides the viewer with an interface onto an entire world. A viewer of television can see and hear other people, experience physical phenomena, witness various events, and so on — many of the components of a perceived existence. Of course, this is just visual and audio input, but these are perhaps the most critical in the daily assessing of our perceived reality.[12]

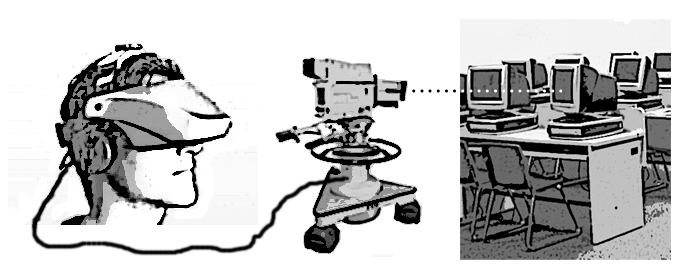

We can propose a situation where a subject is wearing a kind of virtual reality helmet with goggles with a headphone/microphone set. The goggles feed them with continuous television video input. The subject has worn these goggles (and the other apparatus of the helmet) for their entire life; they have been led to understand that what they see and hear is a real world that is external to them, in a manner somewhat analogous to the inhabitants of Plato’s cave. They see streets, buildings, trees, grass, people, and so on. All the phenomena they perceive via their video goggles are physically consistent: they see the sun and stars, observe the changing seasons, and other physical phenomena, and perhaps even attend lectures on physics and chemistry. Everything they perceive is uniform, and follows the physical laws that they have learned.

One day, however, they see a computer lab — again, of course, via their goggles — filled with cathode-ray tube (CRT) video monitors.

|

|

|

Figure 1. The goggle-wearer “sees” a computer lab filled with CRT video monitors. |

They look at the computers and take a look at the screens of the monitors. They see images there, perhaps the computer logo or a picture, but they also notice a sort of buzzing line or band that seems to move slowly across the screens from top to bottom every few seconds or so.

Anyone who has watched television has probably seen this at some point: when you see a CRT computer monitor on a television show, you will see the scanning lines of the monitor “captured” by the television camera. On television, computer screens appear to have a kind of scrolling band, because the television cameras are unable to portray a “static” computer screen — they actually capture the scanning action of the CRT computer monitor displays.

In other words, if you try and point a television camera at a CRT computer screen to record the image there, instead of seeing the stable image that your eyes perceive, you get a flickering image or a line rolling across the screen. This flickering or “banding” is caused by the difference in scanning frequency between the CRT computer monitor and the television camera capturing the image. The difference also comes from the way the phosphor dots of the CRT computer monitor are perceived by the human eye as compared to the way that they are picked up by the television camera.[13]

In a CRT computer monitor, an electron beam scans in a horizontal direction across the back of the screen. When the beam hits the screen, it lights ups the phosphor dots on the screen, and these glow, just for a fraction of second. The beam moves across the back of the screen fast enough that the entire screen seems to glow continuously. So, we see a steady image. A television camera, however, “perceives” the dots as glowing for a much briefer period, and thus they record what seems to be a flickering or “banded” image. Even if the CRT computer monitor has a scanning rate of 60 Hz and the television camera recording the image is taking a frame every 1/60 of second, the band that one sees on the monitor will roll across the screen the because monitor and camera are not synchronized.

Returning to our scenario, the goggle-wearer observes the CRT computer screens in the lab and notices this flickering band. They ask the person whom they “see” in the lab what this flickering is. The person in the lab, of course, sees no flickering or banding whatsoever. That interference is the product of the interface between something in the external scene or simulation that is being filmed, i.e., the computer lab, and the goggle-wearer’s perceptual mechanism — i.e., the video goggles.

In similar manner, if a person were watching a television screen, but told that it was a window onto the real world, they would be able to determine that it was not, in fact, the real world. This is because they could communicate through that “window” with the person working in a lab, who had explained to them how CRT computer monitors work, and who had stated that there was not any flickering or banding at all in the typical operation of such monitors.

This, then, is a reality test, wherein the information needed to determine if the observed world is real can be found through observation of that “world” itself and through logical reasoning. The test in this case is accidental: the setup of the simulation itself has given rise to a phenomena — the flickering or banding — that can only be explained by the postulation of the existence of some kind of mechanical interface. The participant or “goggle-wearer” would be able to conclude from within the simulation that something was amiss, since the physical laws they had learned could not explain the phenomenon they were observing. The only logical hypothesis would be that they were experiencing a mediated or simulated existence.

Extrapolation to the Observed Environment

The scenario described above clearly delineates the nature and role of observer and the configuration of the simulated reality. The simulated reality is a continuous televised scene, one that includes streets, buildings, trees, grass, and, of course, the lab with the CRT computer monitors. The observer receives the scenes as their visual input, taking them for a real world — indeed, the only world they have ever known. We on the outside can argue that while the observer may think that their world is real, it actually is no more than a projected image. We know this because we can see the mechanism of the simulation in its entirety.

However, this “God’s eye view” is something that we do not possess in our own reality. We are inside the system, and everything that we perceive we tend to assume has a material reality. But our goggle-wearer assumes the same — at least until they stumble across the evidence that something is amiss. That evidence is, in short, a physical phenomenon that the observer can see rather easily, but a phenomenon that does not fit with their existing knowledge of their “physical” universe. According to the physical laws that the goggle-wearer has worked out over the years in living inside the simulation and learning physics there, there should be no interference pattern where one ends up being observed.

The idea of an “interference pattern” is an important one. Interference patterns come from two systems that are in some way dissonant, unsynchronized, or incompatible. In a physically consistent material reality, one would not expect any unexplainable interference patterns. More particularly, interference patterns usually require an interaction between two sources. In our reality, we encounter interference patterns only when observing, for example, two sets of waves intersecting.[14] We do not observe interference patterns where there apparently is only one set of waves — something that is happening in our television model described above, where the only apparent set of waves are those from the CRT computer monitor.

In everyday observation, in fact, if we see an interference pattern and have accounted for only wave source, we must go looking for the second source. For example, we might observe that a car has polarized windows, but only because we, the observers, are wearing polarized sunglasses and so a perceptible interference pattern is created.[15] The most important thing is that we might be able to detect that we are in a simulation if we observe a physical phenomenon that is explainable solely through the postulation of the presence of some kind of interface through which the simulation is inputted to us — in our model above, it is the television system and video goggles.

How do we move from such a model to real-life experiment? Unfortunately, it is not quite so simple. First of all, we are required to make what is a rather slippery distinction between what we might call a physically consistent material reality, such as the one we assume that we live in from day to day, and a simulation of the kind postulated by Hilary Putnam and rendered as a nightmarish existence by the makers of “The Matrix” film.

But let us pass over that problem for a moment, and look around us. We apparently perceive a physical reality, comprising matter made of atoms and their constituent sub-atomic particles. When we observe this physical realm, we might find the kind of aberration that our goggle-wearer encounters. Perhaps it is something as simple as the odd interference pattern we observe when sending even single photons towards a photographic film in the famous double-slit experiment.

To “check” our reality, we might talk about constructing a test where we take a physical phenomenon that does not easily fit with our current model of physics. We then could postulate that our experienced reality is, in fact, a simulation. We would go on to posit some kind of true, external reality beyond our perceived one, since ours is just a simulation. We would conjecture that the mysterious physical phenomenon that we have observed is the result of the “interference” between our mode of experiencing that simulation — i.e., our “goggles” — and something in the simulation itself.

Admittedly, this is a strange kind of science, where such an odd explanatory model — a whole external reality beyond the one we typically perceive! — is used to address a physical phenomenon. Indeed, this kind of conjecture certainly violates the principle of “Occam’s Razor.” But the point here is that the construction of such a physical test might be possible, if our “television” analogy is valid. We might be able to detect a simulation from within the simulation.

Directions for Further Investigation

A problem in attacking the question of simulation versus reality with the science of physics is that if we are in a simulation, we are working with a physics that is itself a product of the simulation. The philosopher David J. Chalmers calls this the physics “used by my envatted self in the counterfactual world.”[16] In other words, in such a scenario when we observe matter and space, we are actually just observing the inside of a simulation. In that scenario, physical laws — such as the “fact” that c is the speed limit of the universe — are not laws at all, but simply the parameters of the simulation. Returning to our analogy, we might ask whether such physical constants or parameters might tell us something about the possibility of determining the existence and nature of the simulation. In our television analogy, it was the inexplicable interference patterns that led to the conjecture that there was a simulation running. In this case, it might be the parameters themselves that suggest we are in a simulation rather than a physical reality.

This paper has assumed a certain rough definition of “physical reality.” Earlier, we used the term “perceived reality,” because we can only really talk about what we or our scientific instruments can detect or perceive. Naturally, many philosophers and scientists will affirm that there is indeed a distinct material reality, and that our perception of it is irrelevant to its definition. However, in our television scenario, the mode of perception matters, since that is what reveals the simulation. Moreover, in our television scenario, there is a clear difference between material reality and simulation. And in our actual world of experience, if that is also the case, the construction of a testable hypothesis might be possible. As we noted earlier, interference phenomena of the kind encountered in the double-slit experiment may indicate a direction for future investigation.

But in contemporary physics, the problem is that while we experience an apparent physical reality every day, we have been unable to pin down quite what it is. In fact, asking “what it is” may not even be an appropriate question. Historically, when scientists looked into the structure of matter, they took a kind of reductionist view, seeking to find smaller and smaller component parts: atoms, protons, neutrons, electrons, quarks, and so on. But there seems to be a limit to the empirical method here, as we reach the limit of our ability to carry out detection, observation, and measurement at a certain scale.[17] Physics falls into asking questions such as “Is matter, in the end, actually composed of empty space?” These kinds of questions are suggested by recent physical theories involving spatial “strings” and “membranes.”[18] Hilary Putnam posited the scenario of our simply being “brains in a vat,” but the question really is “What’s a vat?” If we cannot define our perceived reality very clearly, we certainly are going to be unable to define what a simulation might be, nor the external reality that might be running it.

In some sense, modern physics is already positing a two-level existence, insofar as it speaks of both an observable physical world that we live in every day, and a kind of “substructure” beneath that of “strings,” “membranes,” or pure space. Of course, that substructure is not quite the same as a simulation that is being actively manipulated by some outside force. But we are still talking about the difference between what seems to be a world of perceptible matter and a “lower level” world or “bottom layer” that is something else — indeed, perhaps not a “thing” at all. What that world behind this one might be is open to speculation. In our analogy above, it was a continually projected television image. Chalmers, cited earlier, has looked at various possibilities, including the idea, related to that of Stephen Wolfram and, earlier, Konrad Zuse, that “behind” our perceived physical universe is a computational one[19].

These ideas present difficult problems in several respects. For one, the supposition of “another level” of reality, e.g., one that is running a simulation, leads to the classic problem of infinite regress: is that “other level” itself simulated? Also left unanswered is the question of what the “substrate” of these realities might be; at some level, is there a distinct substrate that the virtual realities lack? Even in a simpler scheme, where we might conjecture the denizens some kind of solid reality perpetrating a simulation to which we are subject, there is the issue of the medium through which the simulation is taking place. If we are living in a simulation, a scenario Bostrom describes, we need to consider how it might be constructed. More profoundly, if we are living inside a simulation, do we have the tools to find out or to talk about intelligently? This paper, of course, suggests that we might be able to do so, but not without difficulty.

Related to this is the problem of differentiating between the observer and the observed reality. Contemporary physics implies a fairly distinct difference, even with the suggestion of observer influence posited by quantum mechanical theory.[20] We walk around feeling ourselves to be observers of a rather separate material world. Even physicists usually consider themselves as entities carrying out experiments using apparatus that is separate from themselves. But both we and that world are made of the same basic physical substance — atoms, “strings”, whatever — and yet one side is conscious of the other. That is, how can one group of atoms — ones that happened to be configured into the form of a human brain — be conscious of, observe, and measure another group of atoms, the ones comprising the external, material world?[21]

On an even more subtle level, a real problem might be a model where, in fact, there is not another reality beyond our perceived one, and our perceived reality is the only one. This would prevent us from putting forward an explanatory framework that relied upon the postulation of some further substrates beyond the ones we usually observe, but it would lead to a host of other questions.

Finally, most challenging might be a look at the philosophical tools themselves that we are using. Perhaps it the very nature of language, with its prepositional bias toward hierarchies, that has led us to build problematic models that deal with “levels”, “substrates”, “components” such as sub-atomic particles and strings, and so on — models that ultimately lead to the kind of apparently irresolvable and paradoxical questions we have encountered here. The primary languages of physics have been German, French, Russian, and English, but one wonders what a physics that arose in a non-Western language framework might have looked like. Might it have had philosophical or at least descriptive tools that we lack?

This paper has addressed one aspect of the larger philosophical issue of reality versus simulation, through the adoption of a basic physical model. In that model, there is an observer who believes that they are having a direct, unmediated experience with an outside material reality. In actuality, the observer has been interacting with a televised simulation. They discover this through a relatively simple observation: that the interference pattern they perceive in a certain situation seems to have no source. They conclude that since interference patterns are always the result of at least two sources, the second source must be from the very mode in which they perceive their world. The key point here is that it may indeed be possible to construct a physical test for this kind of simulation. More significantly, this means that at least in this kind of case, one can detect a simulation from within the simulation itself.

[1] I extend my appreciation to David Spolum, Sam Durso, and Craig Merow for their enlightening and clarifying discussions concerning the topics treated in this paper. Two of former students, Maxwell Mangel and Michael Bruns, provided enthusiastic input and inspiration in the initial research for this paper.

[2] For an introduction to the “Brain in a Vat” scenario, see the first chapter of Hilary Putnam, Reason, Truth and History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981). “The Matrix” film adopts Putnam’s scenario, along with a number of other philosophical constructs; see Joel Silver, producer, and Larry and Andy Wachowski, directors, “The Matrix” (Burbank, CA: Warner Brothers, 1999).

[3] See Jim Baggott, A Beginner’s Guide to Reality: Exploring Our Everyday Adventures in Wonderland (New York: Pegasus Books, 2006); Christopher Grau, ed., Philosophers Explore the Matrix (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); and William Erwin, ed., The Matrix and Philosophy (Peru, Illinois: Open Court Publishing, 2002). Another film from this period exploring this same issue — a bit more crudely but also more concisely than “The Matrix” — is “Thirteenth Floor,” roughly based on the 1950’s science fiction book, Daniel F. Galouye’s Counterfeit (also published under the title World Simulacron 3). Another film venturing into simulated realities, again from this same period, is David Cronenberg's “eXistenZ” (1999).

[4] Nick Bostrom, “Are You Living in a Computer Simulation?”, Philosophy Quarterly 53.211 (2003): 243-255.

[5] The question of whether some of the results of quantum physics represent violation of physical laws (such as action-at-a-distance) is a complex one. There is a great deal of literature on this subject, but for a recent examination of the issue see Bruce Rosenblum and Fred Kuttner, Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006).

[6] The relationship between the senses as an “interface,” the role of consciousness, and external physical phenomena has been discussed extensively by the neuroscientist Karl H. Pribram; see, for example, Karl H. Pribram, Brain and Perception: Holonomy and Structure in Figural Processing (Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1991). From a physics perspective, this question was explored in-depth by the physicist David Bohm, who worked for a time with Pribram; see David Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980).

[7] Putnam, 5-6.

[8] There are a number of discussions of Putnam’s scenario; note, for example, Michael Huemer, “Direct Realism and the Brain-in-a-Vat Argument,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 61.2 (September 2000): 397-413; Marian David, “Neither Mentioning 'Brains in a Vat' nor Mentioning Brains in a Vat Will Prove that We Are Not Brains in a Vat,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 51.4 (December 1991): 891-896; and Graeme Forbes, “Realism and Skepticism: Brains in a Vat Revisited,” The Journal of Philosophy 92.4 (April 1995): 205-222.

[9] Putnam, 6.

[10] See Putnam, 22.

[11] Ibid., 22 and 50 et ff.

[12] It is noteworthy that the science of physics relies most heavily on the visual sense in terms of experimentation and data gathering. In “pre-modern” societies, of course, other senses, such as smell, taste, and touch, were equally important in assessing the external environment. Contemporary societies — and contemporary physics — perhaps have become overly biased towards the visual and auditory. For a discussion of one aspect of this problem, see Paul Stoller, The Taste of Ethnographic Things: The Senses in Anthropology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989). Also note Anthony Synnott, "The Eye and I: A Sociology of Sight," International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 5.4 (June 1992): 617-636 618 (1992), and the discussion of the role of sight as the dominant sense in philosophy in Shadi Bartsch, The Mirror of the Self: Sexuality, Self-Knowledge, and the Gaze in the Early Roman Empire (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 45 et ff.

[13] For technical details on this effect, see E. B. Bellers, I. E. J. Heynderickx, G. de Haan. and I. de Weerd, “Optimal Television Scanning Format for CRT-Displays,” IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 47.3 (August 2001): 347-353; also note Vlado Damjanovski, CCTV: Networking and Digital Technology (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2005), 110.

[14] Of course, in quantum physics, interference patterns have been observed even in cases when only one photon at a time was allowed to pass through a slit apparatus. What this might suggest about the model of material reality currently held by physicists sometimes seems rather unclear, both in terms of physics and philosophy; see Wolfgang Rueckner and Paul Titcomb, “A Lecture Demonstration of Single Photon Interference,” American Journal of Physics 64.2 (1996): 184-188.

[15] I wish to thank Theodore S. Coxe, Jr. for pointing out the relevance of this phenomenon.

[16] For a further discussion of this, see David J. Chalmers, “The Matrix as Metaphysics,” in Grau, Philosophers Explore the Matrix, 166.

[17] As of this writing, the new Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is still under construction; the hope is that this massive device will reveal the Higgs boson, which will help physicists complete what is known as the Standard Model of physics. More specifically, experiments at the LHC may reveal how other elementary particles acquire mass. Regardless, there will likely be as many questions raised as answered; see John Ellis, “Beyond the standard model with the LHC,”Nature 448 (19 July 2007): 297-301

[18] For one recent look at this issue, see Lee Smolin, The Trouble With Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2006).

[19] Chalmers, 137-139; also note Stephen Wolfram, A New Kind of Science (Champaign, Illinois: Wolfram Media, 2002), and Konrad Zuse, “Rechnender Raum,” Elektronische Datenverarbeitung 8 (1967): 336-344.

[20] An early paper that touches upon this subject is Nobert Wiener, “The Role of the Observer,” Philosophy of Science 3.3 (July 1936): 307-319; also note the following famous study: Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen, “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?” Physical Review 47.10 (May 1935): 777-780.

[21] For a paper that touches upon this topic in quantum physics, see Harvey R. Brown, “Mindful of Quantum Possibilities,” The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 47.2 (June 1996): 189-200.

-------------------

Assistant Professor of Philosophy, History, and History of Science

The University of the Arts

Philadelphia, PA 19012

bolshin@uarts.edu

tel: 215.351.9744

Comments

Who needs reality?

The reality in which all of these theories are grounded may be uncertain, nevertheless, even speaking of alternate realities, we reference "this one." When "this" become the alternate reality, then we will have a true paradigm shift.

Physics, reality, and inquiry ....

"a new object for the study of physics might be about the nature of the mediation — we might even begin to develop a kind of “physics of mediation”."

"observed physical phenomena may actually be said in some respect to be the brain examining itself"

More on brains, senses, and the question of reality

Olshin's response - 23 December 2007

Dr. Grobstein, in his comments on my article “Reality Check: The Possible Detection of Simulated Environments Through Observations of Selected Physical Phenomena”, does a great job of extending the question further. In short, Grobstein makes the point that all perception is mediated, and the question is why one is inclined to choose one mediation as “real”. Grobstein is interested in perception, and he uses the example of the famous “duck-rabbit” optical illusion as an example of the experience of such arbitrary switching between mediation modes. Grobstein is certain right in his assertions that my question can be expanded, or even “exploded” — that is, in the final analysis, “we can't ever establish based on observations that we are REALLY ‘a brain in a vat’ or REALLY not a ‘brain in a vat’”. Of course, my goal in the paper was a more limited one: I was looking primarily at whether one could detect that one was in a “Matrix”-type virtual reality.

Dr. Grobstein and I are going to continue this discussion, but for now I want to move it in the direction of physics. Part of my intent in the “Reality Check” paper was to suggest — very tentatively — that we might want to re-examine the way we do some physics. That is, we might want to include questions of perception (and, certainly, Grobstein’s ideas on “mediation”) when talking about physical phenomena.

Now of course, people have been talking about this for a while, particularly in relation to quantum physics in general, and perhaps the classic slit experiment in particular. One of the most recent examinations is found in Bruce Rosenblum and Fred Kuttner’s Quantum Enigma: Physics Encounters Consciousness. But even that book — which presents some fairly novel interpretations — does not talk about perception or “mediation” in quite the way I have or Grobstein does. In other words, in a simple way.

What I was suggesting in my paper was that certain physical phenomena — perhaps even the odd results of the slit experiment — might be indications of a mediated perception. This is based on a supposition that in a fully unmediated universe, all physical phenomena should be uniformly explainable and consistent. Inconsistencies, such as the odd results of the slit experiment, might be an indication not only that our experiences are mediated (which Grobstein says is certainly the case anyway), but also that we can learn something about the nature of that mediation. In other words, a new object for the study of physics might be about the nature of the mediation — we might even begin to develop a kind of “physics of mediation”.

By contrast, contemporary physics continues to use tools based on a very particular model of perception. This model implies that our senses are perceiving some kind of ultimately tangible objects, or at least fields and forces, that are “out there”, outside us. Physics works towards moving deeper and deeper into discovering a “bottom layer”. After a brief delay due to a mechanical problem, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) will restart in 2009, and its aim, at least in lay terms, is “to study the smallest known particles — the fundamental building blocks of all things.” The LHC, based in Europe, is the largest physics experiment in the world, and certainly its aim of making new discoveries is a noble (perhaps even “Nobel”!) one.

But as a philosoher/historian of science, I might also suggest that we begin talking about what is it we are looking at in such experiments. More particularly, at some point, we will need to address the model of current physics, and its assumption that we somehow are perceiving a describable “external” world. What might be the alternative? At present, I am starting to consider a new model, and I look forward to engaging Grobstein in the development of this model. All I wish to say at this point is that this model subtly implies that observed physical phenomena may actually be said in some respect to be the brain examining itself. The closest analogy I might present is through what are known as “phosphenes”, an entoptic phenomenon of pattern creation by the brain, or “form constants”, which are complex patterns experienced in altered states of consciousness. Physical phenomena which apparently occur outside us, including wave phenomena, may actually all be happening in our heads...

on brains in vats: who needs "reality"?

Intriguing, in several different ways. Among them is that one doesn't need anything quite so elaborate as interference patterns or televisions to discover that what one sees is influenced by "the very mode" one uses to see. Optical illusions suffice to make this point.

"Simulated" implies, though, more than that. Most importantly, it implies not "real," not the thing as it actually is. The television set without the interference pattern is the "real" thing; the one with it is not only mediated but results from a "simulation," a process that obscures or entirely hides "reality." The notion of "simulation" also raises the question of an agent and its motivations: who is responsible for the simulation and why are they creating it?

While the notion of "mediated" follows fairly directly from the awareness of two different ways of seeing the same thing, its less clear to me that "simulated" does. How does one decide that it is the television set without the interference pattern that is the "real" thing rather than the one with it? One could, I suspect, come up with an equally good though quite different story of the latter sort (particularly if one were genuinely inside the "simulation" instead of having conceived it oneself). And why presume that all of this involves an external agent with its own motivations?

Here the parallel to optical illusions is particularly relevant. One sees curved lines because of the mediation of one's brain. One is aware of the possibility of seeing straight lines because of the mediation of one's brain together with something else, perhaps a ruler. The point, of course, is that both ways of seeing are "mediated." Neither is "unmediated" nor "real." And the same could, of course, hold for the television sets with and without the interference pattern. There is, on the face of it, no reason to presume one or the other is "real, and the other affected by the "simulation." They could equally well both be mediated. That in turn would obviate the need to raise the question of an external agent, to say nothing of wonder about its motivations.

All this raises some very interesting questions not only about an essential premise of the television/interference pattern story, but about our ways of making sense of the world in general. "there is an observer who believes that they are having a direct, unmediated experience with an outside material reality." Perhaps though there is actually no such thing as a "direct, unmediated experience with ... an outside material reality"? Maybe the notion of "unmediated" and "reality," together with the puzzling/troubling features of the "brain in a vat" scenario and the analogous Matrix situation, are themselves "mediated," the product of our own brains rather than something that exists independent of them?

With that thought in mind, let's start over. Suppose one has a suspicion that all human experiences are always and inevitably mediated, in the sense that they depend not only on what's out there but other unknown things as well (including things involving one's own nervous system). One might well want to do away with the inherent uncertainties and insecurities of such a situation. And so it might make sense to fantasize something like "having a direct, unmediated experience with an outside material reality." At least then one would know for sure what is going on (or thinks one would). But that in turn raises the awkward possibility that one is being systematically deluded by someone (or something) out there, and the awkward question of whether that someone or something is in turn being deluded by someone/something else.

Perhaps one is better off simply accepting that all experiences are inevitably and unavoidably "mediated," by oneself if not also by things outside oneself, that there is no such thing as "having a direct, unmediated experience with an outside material reality." That would, of course, leave us with inherent uncertainties and insecurities, but maybe that's not actually such a bad thing? Maybe one could get used to the idea that all experiences are mediated, maybe even enjoy it? There is, after all, some appealing adventure in being able to count on there being a way to see things other than the way one has been seeing them. Maybe the adventure of exploring the (infinite?) variety of mediated views more than offsets the uncertainties and insecurities of failing to achieve an "unmediated experience"? One may certainly find less appealing ways of seeing things, but may also find more appealing ones.

But where does that leave us with the "simulation" problem? Is there an observation we could make that would show we're REALLY a "brain in a vat"? We can certainly make observations that established that what we see is "mediated," perhaps even by something outside ourselves (a blur gets clearer when we put on our glasses). But if we take seriously the idea that everything we see is "mediated" then all observations, those included, will fail to meet the test of "having a direct, unmediated experience with an outside material reality." From which it follows that we can't ever establish based on observations that we are REALLY "a brain in a vat" or REALLY not a brain in a vat, for that matter. We can show that there is a second way to see things, perhaps better for some particular set of purposes, but never that there aren't some additional ways to see things that haven't occurred to us yet.

What all of this suggests is that the "brain in a vat" and Matrix problems might not actually be questions about "reality" at all but rather questions about our own brains and their mediated interactions with ... whatever is outside them which we cannot see in an unmediated way ("Of that which we cannot speak we must remain silent" ... Wittgenstein). From this perspective, what's important is not the answer to the question of whether we are in fact living in a simulation but rather that the question itself can occur to us. That it can means we (our brains) have the capacity to conceive new ways of understanding ourselves and our relation to the world. And hence the incentive to further explore additional ways of being and relating to the world. Maybe that's enough, more than enough? Who needs "reality"? We may not be able to "detect a simulation from within the simulation itself" but we can certainly detect mediating influences on our perception and use those to conceive new worlds.

Post new comment