Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Risk and Innovation

Living a Life of Risk, and Why:

Encouraging Innovation in Individuals and Communities

Paul Grobstein

24 October 2007

From prior discussions

- Is risk taking important? Why? Innovation?

- Are there, intentional/unintentional cultural practices that inhibit risk taking? innovation?

- What is the role of leadership in communities? In risk-taking/innovation?

- Is being "generous" with each other enough?

- What are the differences/similarities for faculty/staff/students?

From This Isn't Just My Problem, Friend (1991)

an older teacher took me aside one day to give me some friendly advice. He'd noticed that I liked to think, and liked to try and get other people to think too. What he thought I ought to know was that you couldn't teach people to think, and furthermore that if I spent too much time thinking myself I'd end up losing my job, because that was not what the job was all about. What the job was all about was looking at what was being done around me, learning to do what everybody else around me was doing, and trying to do it better than them, so that I could be more important, and they could try and be more important by trying to be better than me. I couldn't honestly believe that was what the job was, but he was right in one sense at least. I did keep trying to think, and did keep trying to get other people to think, and I did lose that job.

Addendum

Paul's real problem is that he insisted on being judged by his own standards

And on ...

10 May 2001

The discussion, for me at least, moved too quickly to a sharing of thoughts about general evaluation procedures in academia, and possible needs for changes in them, to give me a clear sense of the evaluation made of my own "scholarship". There was, in addition, little or no discussion (as I remember it) with explicit reference to my efforts to move toward a new form of "academic/intellectual identity ... one in which the borders between research and teaching, between research/teaching and college service, and between research/teaching/ college service and my "outside" professional activities are increasingly blurred."

The upshot is that with regard to two parts of my recent activities to which I attach particular importance, my web development/publication activities and my exploration of possible ways to conceive academic/intellectual activity in less traditional ways (which, among other things, reduce some of the sense of conficting time obligations associated with three independent tasks), I do not have a clear sense of whether the College (ie the Appointments Committe and/or the President and/or the Provost) does or does not share my sense of "satisfaction and pride" in my professional activities over the period reviewed.

22 September 2003

Occurs to me that if we're serious about being a community of "scholar/teachers" that the annual report request might support this by asking not only for the items it asks for but also for novel achievements in the realm of teaching and/or blending scholarship and teaching. As it is, the report request suggests a value structure that sets scholarship against teaching by only noticing/valuing the former

7 June 2007

While I fully appreciate the clarity of the notion that a faculty member is free to do whatever research they wish (and can demonstrate success at) but has an implicit obligation to fill particular teaching roles defined as necessary by the department/discipline, I urge continuing attention by the Appointments Committee to two problems with that position.

One problem is that a rigidly defined teaching obligation perpetuates an uncomfortable (and I believe unnecessary) belief that research and teaching are conflicting activities, a belief that can hamper both research and teaching. I would like to think my own record establishes that research and teaching can, in principle, be complementary rather than conflicting activities. The other problem, perhaps even more important, is that the notion of an implicit contract to fill particular teaching roles tends to discourage faculty from playing creative, and potentially revolutionary, roles in the ongoing evolution of the disciplines of which they are a part. It is my sense that disciplines are shaped and, ideally, continually reshaped by the continuing re-evaluations and resulting decisions of faculty members, individually and collectively, as

to what courses are and are not "necessary". In lieu of that, disciplines tend to ossify in tradition bound curricula, and to put unnecessary and undesirable pressure on faculty to sustain them rather than to explore potentially more productive paths.

While there will inevitably be disagreements among faculty about what does and doesn't constitute "esssential" teaching obligations at any given time, I think the health of departments and of the College as a whole are best served by encouraging faculty to challenge existing understandings if they are willing to invest time in creating alternatives whose usefulness (or lack thereof) can then contribute to further discussion and evolution of departmental understandings. There are, of course, larger issues at stake here: expectations by people and institutions beyond the College of what constitutes appropriate curricula for various "certification" and "accreditation" purposes. Here too, though, I think we best serve our commitments to intellectual leadership in the culture at large by ourselves seriously and continually evaluating and re-evaluating the worth of the courses we offer rather than simply defaulting such judgements to external expectations.

The bottom line

Faculty face disincentives for risk-taking/innovation that are not entirely dissimilar from staff/students

A core problem - definition of achievement in ways that reflect lessons of past rather than promise of future

I do believe that tradition becomes

A dangerous tool in the hands of some

It blocks new ideas like the hard red clay

And so the rain comes to wash it away.

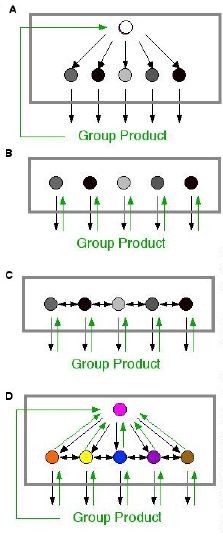

A path towards getting it less wrong for all?

|

|

Comments

I don't think you can teach

Teaching thinking ....

But is providing a rich

But is providing a rich enviroment equivalent to teaching people to think, or enabling them to learn how to think?

Is a rich environment required to learn how to think? Can a person learn in a vacuum?

And I have to get to work, or I'd set about answering those questions.

changing structures in order to change the way people think?

One response to these questions evolved during a conversation, yesterday, about re-ordering structures for decision-making @ the college. Can changing structures change the way people think about problems? Here's one account.....

I know I've had 'aha!'

I know I've had 'aha!' moments, conceptually, and to some extent and sometimes they were arbitrary ...

No, that's not true. I realized that I was white (re: status), (in many ways) privileged, and a closet-case queer because of my participation in the Tri-Co Summer Institute, which was an intense and rich environment; I understood the arbitrariness of gender categories when I read a brilliant article which precisely defined the terms used by the Romans to describe sexual practice - they had no words which correspond to 'homosexual' or 'heterosexual', because for them gender was secondary to power and dominance in defining sexual practice; and I realized that I am genderqueer/I came to identify as genderqueer because of Susan Stryker's visit to campus, during which she visited two of my classes for a total of four and half hours of listening to her talk.

So. Seen from that perspective, nurturance is vitally important to intellectual development; but I am not convinced that everyone has both the inclination and the capability to produce knowledge.

But perhaps my background is, in this particular sense, unusually nurturing. Tri-Co is an unusual program, and Susan Stryker in two classes doesn't happen just any semester; and I've always gone to schools where I was permitted/encouraged in my inquisitiveness, though not necessarily in high levels of intellectual-personal risk-taking. I can't attest to the quantity/quality of development of others who shared the above experiences ...