On the phone a few weeks ago, my dad told me that I had to “root hog or die.” I had just gotten done working at my job on-campus and was exhausted, but “root hog, or die” is just what I had been, and always have been doing. Survival is what we do best in my family, and for seven years now I have been struggling to figure out the best way to survive in an environment I knew nothing and still know very little about. For four years, I was a full-scholarship student at a private boarding school, and now I’m a working-class woman at Haverford College. My experience is one that doesn’t quite fit in at Haverford; my cultural experience from rural, working-class central Pennsylvania is much different than that of many of my upper-middle class counter parts, and even that of my working-class urban peers. I have trouble finding anyone else who knows what its like to go hunting, to use a chainsaw, to drive a pick-up truck up a mountain, or having friends who are the same age but without a high school diploma and with two children.

I like to go home because I know I’ll always be able to fit in there, and I will always feel somewhat out of place at a place like Haverford. Sometimes, though, I feel guilty when I’m at home. My education has given me a certain amount of unexpected upward social mobility that has, whether I like it or not, changed the way I see the world around me. When I see my friends who already have children, or are working full-time at factories, or have only had the opportunity to go to community college, going back to Haverford feels like an unwarranted escape from the real world. My class gives me the good fortune to have had experiences that give me a fuller perspective and understanding of both the worlds that I’m a part of. As scholar Donna Langston explains in her beautiful essay “Who Am I Now?”, “Class is complex and has different meanings and experiences in different settings. There is a difference between the urban working class and the rural working class. Class is defined differently in African-American, American Indian, Asian-American, and Latino communities. There is a very complex system of class differences and privilege among the working class” (Langston 71).

This diversity, however, is understood by few, and Langston, although a woman from a working-class background, is educated (a PhD to be exact). In most cases, the working-class perspective is unacknowledged by many institutions and disciplines within those institutions. Langston describes her experience in academia as leaving her with “conflicting feelings and a lot of guilt” (Langston 71), and that her working-class background leaves her marked “in academia and that my [Langston] middle-class education marks me in working-class settings” (Langston 71). Our guilt comes from our fear for our loved ones. bell hooks, another scholar well-known for her work on class and refusal to abandon her working-class perspective in her scholarship, describes in her essay “Keeping Close to Home: Class and Education” that her parents “feared what college education might do to their children’s minds even as they unenthusiastically acknowledged its importance” (hooks 100). Our parents fear that “we might learn to be ashamed of where we had come from, that we might never return home, or we would come back only to lord it over them” (hooks 101). I remember a few nights before I left for the first time for boarding school my father reminded me never to forget my roots, and I never have. hooks eloquently describes similar intentions: “I did not intend to forget my class background or alter my class allegiance” (hooks 102).

I have to fight the urge sometimes though to feel like my experience is not legitimate or useful in the “academic world.” As an English major, I am required to take Junior Seminar, a course that is meant to prepare English majors to have a well-rounded knowledge of “important” literature in the American/British tradition. All of the poets we have studied thus far with maybe one or two exceptions were well-off, white, Oxford or Cambridge-educated men. The critics we have been reading to complement our work have been professors (again, mostly upper-middle class, white men) at some of the most prestigious academic institutions in America and the United Kingdom, with a few exceptions. hooks reminds me however, that the “most powerful resource any of us can have as we study and teach in university settings is full understanding and appreciation of the richness, beauty, and primacy of our familial and community backgrounds” (hooks 111).

Colleges and universities need the working-class perspective as well. Most of the students at schools like Haverford and Bryn Mawr are upper-middle class and may not have ever been fortunate enough to experience a lot of the things that students like I have been able to see and learn from. There is great beauty in the world of the poor and working-class that in many cases may not ever be considered “art” because of the standards in the academy for what is valued as such. Paul Lauter proposes in his influential essay, “Class, Caste, and Canon,” that:

“An adequate theory of criticism can only be developed by fully considering the art produced by women, by working people, and by national minorities; further, such art needs to be understood in light of its own principles, not simply in terms and categories derived from so-called ‘high-culture,’ or on the basis of the imperatives imposed by careerism or reigning institutional priorities” (Lauter 144).

Lauter sees an important task for those who study literature in examining “hierarchies of taste as expressed in subject matter, genre, and imagery, as well as in conception of literary function and audience” (Lauter 147). I agree whole-heartedly with Lauter. I can find no honest, sincere appreciation of the poetry of William Wordsworth, for example, nor can I easily understand the literary criticism of a scholar like Roland Barthes. I also don’t want to. Despite their influence on the literary world as it is, their work is not contributing to any kind of change or move towards inclusivity. The world of literary studies is stagnant, and is not welcoming any new kind of student with the out-dated rigidity of many programs throughout the US and the world. The advent of new forms of literary criticism like feminist and post-colonial theory have made small dents in changing literary study, but have yet to make much of an effect on what is studied in English curriculums.

Alice Walker’s story of her mother’s garden is a poignant example of what the academy is missing by supporting such an elitist agenda in literary criticism. Walker describes her mother’s garden as mystical, “whatever she planted grew as if by magic” and this magic and her mother’s creativity affected her memories of the poverty she grew up in: “even my memories of poverty are seen through a screen of blooms…” (Walker 241). For her mother, the garden was her art, “her personal conception of Beauty” (Walker 241) and that only when she was working with her flowers was she truly radiant, “almost to the point of being invisible” (Walker 241). Despite her mother’s limited access to education and other resources, she still found a way to making being an artist an important part of her day-to-day life. Walker sees this as a small means of resistance, the “ability to hold on, even in very simple ways” (Walker 242). She also claims that this is something that black women have been doing for generations, but I would go as far as to say that it’s something that all working-class women have been doing for years upon years as well.

We have got to look for art in more places than carefully crafted verse, metaphysical lyric, and dense, inaccessible literary criticism. If Alice Walker can find it in her mother’s garden, then I know I’ve seen it when I help my dad and brothers carefully stack a pile of firewood (there’s more strategy to it than you’d think). I’ve seen it when my mother cooks, when my dad stands over his work bench sharpening a saw chain. Alice Walker got it right; if we can look for the places that poor and working people have survived and they ways in which they pull themselves through, we will surely be able to find the simple art that made them radiant in addition to also being resilient.

Poems by women from Appalachia reflect experiences that can rarely be found in any curriculum in academic institutions. The raw emotion and craving for survival sets their work apart from anything I have ever read before. What’s significant about their experiences and their use of poetry as a medium for conveying them is that these typically poor and working-class women write about sentiments that many working-class students at colleges and universities may be able to identify with. Jo Carson’s poem “49” from her collection Stories I Ain’t Told Nobody Yet: Selections from the People Pieces reads as follows:

I am asking you to come back home

before you lose the chance of seein’ me alive.

You already missed your daddy.

You missed your uncle Howard.

You missed Luciel.

I kept them and I buried them.

You showed up for the funerals.

Funerals are the easy part.

You even missed that dog you left.

I dug him a hole and put him in it.

It was a Sunday morning, but dead animals

don’t wait no better than dead people.

My mama used to say she could feel herself

runnin’ short of the breath of life. So can I.

And I am blessed tired of buryin’ things I love.

Somebody else can do that job to me.

You’ll be back here then; you come for funerals.

I’d rather you come back now and got my stories.

I’ve got whole lives of stories that belong to you.

I could fill you up with stories,

stories I ain’t told nobody yet,

stories with your name, you blood in them.

Ain’t nobody gonna hear them if you don’t

Andyou ain’t gonna hear them unless you get back home.

When I am dead, it will not matter

how hard you press your ear to the ground.

Anyone who has ever had to leave home, and leave a parent or parents behind could connect to this poem. Carson points, though, to someone who left maybe to pursue an education or an opportunity for social mobility. The speaker, presumably a mother, wants to share her stories with her child, to preserve their memories, perhaps in an attempt to prevent her child from turning into what bell hooks describes as a child who is embarrassed about their family’s roots. On a larger scale, I read this poem as asking for those from the working-class in academic institutions to “come home” metaphorically: to come back to the traditions of their family, their culture. Everyone needs for the working-class to break into the American canon: the affluent and the working class alike. The only people who can infuse literature with this perspective, though, is the working-class. There are inevitable barriers to those from lower-class backgrounds getting into academia: tuition, ensuing loans, travel expenses, familial obligations, etc. For those of us who can make it in, there is tremendous value in refusing to forget the details of our experience and continuing to share it with those around us. There is no shame in working with our hands, and there is certainly no shame in telling others about it.

Sylvia Trent Auxier paints a portrait for readers in her poem “When Grandmother Wept” from her collection of poetry With Thorn and Stone: New and Selected Poems. Her illustration is of a woman, stoic and focused, who, although tears fall down her face goes about her work, “the spirit yielding but unbroken still” (8).

When my grandmother wept she did not weep

Head on her folded arms, but all the while

She’d go about her work, and tears would creep

Slowly as though an inch a hard-won mile.

Their passing made no inroads on her face:

Her cheeks were smooth, the lips firm to her will;

And inked in her eyes’ blackness, one could trace

The spirit yielding but unbroken still.

She spoke no word. She seemed to go away

Within herself to some deep silver well

Hewed in the granite years of yesterday,

Water of wisdom pooled in memory’s spell.

From this deep well, to which each one must go

Alone… alone return, she came back to us then

The smile triumphant on her face – as though

Tears never were… would never be again.

I can see my mother, my grandmothers, my aunts, and myself in this poem. My great-grandmother, who only died a few years ago, was famous for her ability to stretch even the smallest meal. My mom always tells me that no matter who showed up to Grandma Johnson’s house, there would always be enough for them. The women in my family are famous for making it work (root hog, or die). Despite irresponsible, sometimes jobless husbands, the women in my family manage to raise their children, put food on the table, and still manage to hold onto some kind of hope or faith that everything would work itself out. The most pure beauty in humankind is being able to witness resilience in spirit; someone being able to hold themselves up despite the burdens that may be weighing them down to the ground.

And I’ll tell you what: that’s something that Cleanth Brooks or M. H. Abrams sure as hell can’t tell me about. These poems are exactly why the working-class needs to be in the academy, and why the academy needs the working-class. The academy hasn’t had to claw and fight to keep themselves and their families alive; their perspective is the most secure maybe in the country. They are the intellectual, bourgeois class. My people are the people that repair their roofs, clean their houses, or cut the wood that they burn in their uppity fireplaces.

Just because I can speak the King’s English doesn’t mean that it’s my native tongue. My dialect deals in the dirt on my hands from putting freshly cut wood away for , the single tear that rolls down my mother’s face when she had to put her father in the ground, the blood that comes out of my father’s rough, calloused hands that break open when he cuts a splinter out with his own knife. Maggie Anderson mentions in her essay “Mountains Dark and Close around Me” that one of her friends, a West Virginian women writer, once said, “I’m a hillbilly, a woman, and a poet, and I understood early on that nobody was gong to listen to anything I had to say anyway, so I might as well just say what I want to” (Anderson 39).

The academy has plenty to learn from me, and I have some things I can learn from them about what I refuse to become. I can find art in simple, unexpected places. Poetry is not a place to demonstrate the advantages that privilege and education have given to you; poetry is a chance to talk with the people around you. Note, I said, talk with, not talk down to. Alice Walker’s mother’s garden talked to people counties around; she was always cutting off a few blooms for someone who came to visit. My great-grandmother could always spare an extra seat and plate of something hot for someone who needed to put something in their stomach. My mother has the faith to let me come here to Haverford and not have to fear me becoming someone she wouldn’t recognize. These silent, wordless conversations are the stuff of human interactions, and interactions with the earth. The academy started far above the rest of the world: Donne, Herbert, Spenser, and Sidney wrote ethereal, metaphysical verse that people now still have trouble reading (or at least I do). Slowly but surely, literary studies have come closer to their human roots, but there is still a deeply rooted hierarchy in literature that inevitably keeps a lot of people out. I’ve made it in, but a whole part of me refuses to subscribe to the elitist standards that keep the rest of my people out.

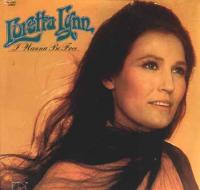

Where I’m from, we think in song:

Loretta Lynn

Patsy Cline

Hank Williams

Merle Haggard

Waylon Jennings

George Jones

They are the redneck poets.

They work, they cry, drink, fight, and love.

Letters don’t keep nobody out because there ain’t nothin’ you got to read to understand what they’re talkin’ about.

Patsy Cline

“I fall to pieces,

Each time someone speaks your name.

I fall to pieces.

Time only adds to the flame.”

Merle Haggard

“And I turned twenty-one in prison doing life without parole.

No-one could steer me right but Mama tried, Mama tried.

Mama tried to raise me better, but her pleading, I denied.

That leaves only me to blame 'cos Mama tried.”

Waylon Jennings

www.youtube.com/watch

“You'd better move away,

You're standin' too close to the flame.

Once I mess with your mind,

Your little heart won't beat the same.

Lord, I'm a ramblin' man,

Don't mess around with any ol' ramblin' man.

Better not!”

Loretta Lynn

www.youtube.com/watch

"To the hills of West Virginia,

From the Johnson County court house

My Daddy worked down in them dark cold mines.

Education didn't count so much as what you had for mem'u

Like the will to live an' a dream of better times.

Daddy never took a hand out; we ate pinto beans and bacon,

But he worked to keep the wolf back from the door.

And it only proves one thing to me,

When folks start bellyaching:

They don't make 'em like my Daddy any more.

.."

George Jones

www.youtube.com/watch

"...I went to see him just today

Oh but I didn't see no tears

All dressed up to go away

First time I'd seen him smile in years

He stopped loving her today

They placed a wreath upon his door

And soon they'll carry him away

He stopped loving her today..."

Hank Williams

www.youtube.com/watch

"...I’ve never seen a night so long

When time goes crawling by

The moon just went behind a cloud

To hide its face and cry

Did you ever see a robin weep?

When leaves begin to die

That means he’s lost the will to live

I’m so lonesome I could cry

..."

My granddaddy loved George Jones. He would sing “He Stopped Loving Her Today” to my grandma. My granddaddy had an eighth-grade education, but his art was fixing cars. He collected cars and tractors, and we still have some of his projects sitting around my grandma’s land. My grandma loved Waylon Jennings, and she still does. He was her favorite “outlaw;” she said pappy would get jealous sometimes of how much she liked Waylon. She had graduated from high school, but had my mother shortly there after, after being married for a few months to my pappy.

The outlaws usually sang about their lost love, getting so drunk they lost their women, getting arrested, etc. Loretta Lynn sang about growing up in coal country, and Patsy Cline crooned about her heartache. My grandparents could relate to their music; they had similar struggles: poverty, alcoholism, and heartbreak. My granddad may have only had an eight-grade education, but he didn’t need a college education to relate to the art of George Jones, Waylon Jennings, Merle Haggard, or Hank Williams.

My mom and dad would play Merle Haggard for us when we were young, and “Okie from Muskogee” and “Mama Tried” are some of my favorite country songs. My favorite memory though is of my mom singing Patsy Cline songs. My mom has a haunting voice. I will always be able to picture her cooking and washing dishes in our old kitchen, humming along to Patsy Cline, “Walking after Midnight.”

I am positive that it will be years before any college in the United States even considers adding a class-based music course to their curriculum, or working-class literature to their English department, but that’s why there are people who take their experiences with them into the humanities and refuse to let them go. That’s why my story is important, and all the other working-class stories out there: from the city, the country, North, South, and even from other countries. Academia doesn’t have to reify the standards of “good” or “quality” art. You can’t judge my experience, or the experience of other working-class people against the qualifications of people that have never had the same kind of challenges that country people have, or working-class people in the city for that matter.

Haverford doesn’t know anything about me, my family, where we’ve been, what we’ve seen, what we sing, why we cry, or why we smile. I’ll tell them though, hopefully someone will listen. Maybe they’ll learn something, maybe they won’t. I hope they do because I’ve sure learned something here.

My culture is about survival; there are people here that have had to learn similar things. I’ll find them, we’ll find each other.

Root hog, or die.

*********************************************

Lyrics courtesy of: www.cowboylyrics.com

Patsy Cline photo:blogs.seattleweekly.com/reverb/patsycline024.jpg

Merle Haggard photo: www.reservebranson.com/blog/uploaded_images/MerleHome300x300-797438.jpg

George Jones photo: www.phillymusicguide.com/shows/george-jones/01.jpg

Loretta Lynn photo:library.thinkquest.org/TQ0312140/ThinkQuest/Jeremy/lynn-loretta2.jpg

Hank Williams photo:comp.missouri.edu/blogs/eathomas/files/2008/03/hank-williams-2.jpg

Waylon Jennings photo: image.lyricspond.com/image/w/artist-waylon-jennings/album-ultimate-waylon-jennings/cd-cover.jpg

Works Cited

Anderson, Maggie. “The Mountains Dark and Close around Me.” Bloodroot: Reflections on Place by Appalacian Women Writers. Ed. Joyce Dyer. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1998. 31-39. Print.

Auxier, Sylvia Trent. “When Grandmother Wept.” Listen Here: Women Writing in Appalachia. Ed. Sandra L. Ballard and Patricia L. Hudson. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2003. 49. Print.

Carson, Jo. “49.” Listen Here: Women Writing in Appalachia. Ed. Sandra L. Ballard and Patricia L. Hudson. Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 2003. 98. Print.

Hooks, Bell. “Keeping Close to Home: Class and Education.” Working-Class Women in the Academy. Ed. Michelle M. Tokarczyk and Elizabeth A. Fay. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1993. 99-111. Print.

Langston, Donna. “Who Am I Now?: The Politics of Class Identity.” Working-Class Women in the Academy. Ed. Michelle M. Tokarczyk and Elizabeth A. Fay. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 1993. 60-72. Print.

Lauter, Paul. “Class, Caste, and Canon.” Feminisms: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism. Ed. Robyn R. Warhol and Diane Price Herndl. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1997. 129-150. Print.

Walker, Alice. “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens.” In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983. 231-243. Print.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Comments

Philip Levine - Poetry for the Working Class

Please see the delightful poetry of Philip Levine, who writes uplifting and resonant poetry about working in the auto factories of Detroit. It may not be rural, but it was a lifeline for me during my college years. Enjoy.