Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Technological Tension in Deaf Culture

Marina Morrison

GIST 4/2/2011

When Technology Threatens Deaf Culture

The deaf community has struggled in recent years to cling to their deaf culture in spite of the numerous technological advancements that are quickly bridging the gap between the hearing and deaf communities. The deaf culture is concerned that these technological advancements will eventually completely eliminate the sense of cohesion and community that exists among members of the deaf culture for fear that , with the aid of technology, many deaf individuals will choose to integrate into the hearing community rather than continue to be members of the deaf culture.

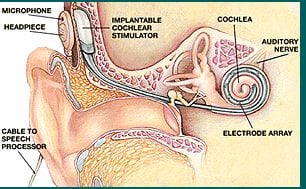

The deaf community consists of two main groups: the ‘deaf’ with a lower case d and the ‘Deaf’ with an upper case D. The ‘deaf’ communities are those who readily accept the use of technology, such as cochlear implants, to aid their hearing as they attempt to fully integrate themselves into the hearing community. Generally, these members of the deaf community do not see themselves as members of deaf culture. Those members who identify as ‘Deaf’, however, do see themselves as members of the deaf culture which they view as a cultural identity rather than a disability. These members of the community generally look down upon the use of technology to integrate into the hearing world and have great pride in their deafness. The Deaf openly use sign language at their workplace and in their daily lives. (Tucker 6). The National Association of the Deaf states that the Deaf “like being Deaf, want to be Deaf, and are proud of their Deafness. Deaf culturists claim the right to their own ethnicity, with their own language and culture, the same way that Native Americans or Italians bong together” (7). The Deaf do have their own shared language that is a highly cohesive factor within the Deaf community. American sign language is a visual rather than spoken language with it’s own grammatical style different from that seen in signed or spoken English. In signed English, each spoken English word has a corresponding sign and uses English grammar.

The debate of the effect of technology on the deaf culture and community has expanded as in 2002 a deaf lesbian couple deliberately created a child who would experience deafness like they had. The two women attempted to find a deaf sperm donor but to their dismay congenital deafness is among the conditions that would disqualify a sperm donor. As a result, they asked a deaf friend with five generations of deafness in the family to act as their donor. The couple considers themselves as a part of the deaf culture as both women were born deaf and feel more a part of the deaf community than the hearing community, “They see deafness as a cultural identity and the sophisticated sign language that enables them to communicate fully with other signers as the defining and unifying feature of this culture.” (Spriggs 283). The couple’s actions are mostly motivated by their desire to have a deaf child to share this culture with and see their actions as no different from attempting to have a girl rather than a boy. The couple states, “Girls can be discriminated against the same as deaf people.” (283). However, although girls may be discriminated against in similar ways they also do not suffer from the inability to hear. The couple’s child was born deaf but some residual hearing in the right ear lead to the possibility of possible technological aid through a hearing aid that would allow the child to better understand spoken English and lip reading. However, the couple decided against the hearing aid in preference of the child becoming more integrated in the deaf culture rather than attempting in any way to assimilate into the hearing culture. There has been great criticism on the couple for their deliberate creation of a deaf child, denying their child a hearing aid, and even for raising the child in a homosexual household. Ken Connor speaks out against their decision, “To intentionally give a child a disability, in addition to all the disadvantages that come as a result of being raised in a homosexual household, is incredibly selfish” (283). Clearly, some are outraged at the idea of a Deaf couple having such pride in their deaf culture that they would want to share this pride and sense of community with their Deaf child. However, other members of the Deaf community also seem puzzled at the deliberate nature of couples actions. Brian Rope, head of the Deafness Forum of Australia states, “I understand where they are coming from…Lots of Deaf parents would like to have a Deaf child, but most of them take what they get.” (283). Additionally, many critics argue that hearing children can be immersed into the deaf culture just as much as Deaf children. Hearing children can learn to speak in sign language and they are also able to understand deaf culture if they are immersed in it. (Savulescu 2).

Reproductive decision making and genetic tests were devised initially to allow couples to have the best possible child they could have with the best possible chance for opportunities and life prospects. For the couple, bringing a Deaf child into the world seemed like the best child they could have in their home since they operate within the deaf culture and this would give the child the best options and opportunities within the Deaf community. The Deaf community appreciates the deafness of others and is critical of those within the Deaf community who attempt to use cochlear implants or spoken English. At Gallaudet University, the only liberal arts university in the nation to serve the Deaf community, there is a tense divide among the students with cochlear implants and the students without, “Cochlear implants are greatly frowned upon at Gallaudet…implanted individuals who attend Gallaudet are usually pressured (often by their peers rather than by staff or faculty members) to remove them or at least not wear their processors.” (Tucker 9). Interestingly, the couple’s decision to not allow their child to have a hearing aid may have been directly affected by this as both women attended Gallaudet University. The students at Gallaudet seem to be Deaf culturists that shun any use of technology that would cause a Deaf individual to distance themselves from their deaf culture. The ASL sign for a cochlear implant even expresses this hatred of technology for the deaf as it “contains a two fingered stab in the back of the neck, indicating a ‘vampire’ in the cochlea.” (9). Parents who have decided to allow their children to have cochlear implants think differently. One parent, Melissa Chaikof, states, “If the cochlear implant has removed my daughters from Deaf culture, and it probably has, then that is fine by me. The Deaf culturist’s opportunities in life are so limited, and my daughters’ are not. Furthermore, it has been the choice of those in the Deaf culture to exclude those with implants from their group.” (9). It seems that those who choose to use technology to aid their hearing are not attempting to distance themselves from Deaf culture, rather they are attempting to increase their chance at more opportunities in life but as a result have received criticism from Deaf culturists and are ostracized from the group.

Clearly, technology has created a tense divide within the deaf community- there are members who accept technology as a way to increase opportunities and life prospects and there are members who consider technology as a threat to the deaf culture that has been built upon the reliance on American Sign Language and the bonding through their experience of deafness. As technology continues to improve on listening devices and hearing aids the Deaf community either will continue to divide or somehow find a place for technological advances within their community.

Works Cited

Savulescu, Julian. "Sign In." Bmj.com. National Institutes of Health, 5 Oct. 2011. <http://www.bmj.com/content/325/7367/771.full>.

Spriggs, M. "Journal of Medical Ethics." Lesbian Couple Create a Child Who Is Deaf Like Them

Normal

0

false

false

false

EN-US

ZH-CN

AR-SA

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

(2002): 283. Print.

Tucker, Bonnie P. "Deaf Culture, Cochlear Implants, and Elective Disability." The Hastings Center Report 28.4 (1998): 6-14. Print.

Comments

response

I did try to make my report as even as possible to present an unbiased view of the debate so anyone reading could form their own opinion on the subject, but I do have strong feelings regarding the deaf and the deaf community. I had a friend in high school who was deaf and he was the only deaf individual in the entire school (my high school had about 2,000 students). However, his deafness never seemed to stifle his social or intellectual life and he had no shame whatsoever in his deafness. It definitely seemed to fit into the idea that deafness as more of a difference than a disability. Besides that personal experience, last semester I did a presentation in my Autism Spectrum class on how Autism is another condition that could be considered culture of its own. The Autism community seems to be arguing for a recognition of it's culture and community in the same way that deaf culture seeks recognition. While doing this report on Autism, I stumbled upon many resources that argued for a culture of deafness. This sparked my interest at the time, but I didn't follow through since it wasn't the condition I was presenting on. Once the panel came around I had already had been wondering about the tensions that exist within the deaf culture for some time and decided it might be something worth speaking on. Regarding the debate, I think it's always hard for communities to accept technology that could potentially disrupt the bonding and cohesion which brought them together in the first place- which would be use of sign language for the deaf. Yet, it seems this technology is being accepted by many in the community, and I think it is their right to use technology to whatever extent they wish and still be recognized in deaf society. I discussed how some students at Galluadet are ostracized if they have cochlear implants, so it seems as though if technology is embraced by someone within the community they are then excluded from deaf culture. I don't think technology poses a threat to deaf culture as long as they don't let it. Sure, technology could cause less deaf individuals to want to learn sign language and more likely to immerse themselves in the hearing world, but a deaf culture would still exist apart from that. So, I believe in the use of technology to those who want it, but I also believe in the importance of diversity and not forcing this technology on the deaf community or using it in any way to eradicate deaf culture.

On being even "handed"

Marina—

I have been tracking the evolution of disability studies for the past couple of years (as well as participating in constructing it, with particular reference to its intersections w/ gender studies; see, for example, Cripping Sex and Gender and Seeing Stigma). Because of my interest in category construction (and destruction and re-construction), I'm particularly intrigued by location of the D/deaf as disabled/encultured. Something I learned @ a disability symposium here @ Bryn Mawr a few years ago— which would add an interesting turn of the screw to your paper— is that (thanks to the acceptance of Sign as a “foreign language” on many college campuses), there are now more hearing speakers of Sign than deaf ones; this distinctive quality of the culture is possessed by those for whom it is a second language (there is a wonderful repertoire of spoken word poetry, btw; you might want to check out some of this), rather than by those for whom it “might have been” a first language.

Your report is a very even-handed (sic) one; what do you think about the debate you’ve reported on here? Why are you interested in these ideas, and where do you position yourself in the spectrum of positions you’ve laid out here?