Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

It's All Greek to Meme: Ancient Greek Theater and the Effectiveness of Dennett's "Dangerous Idea"

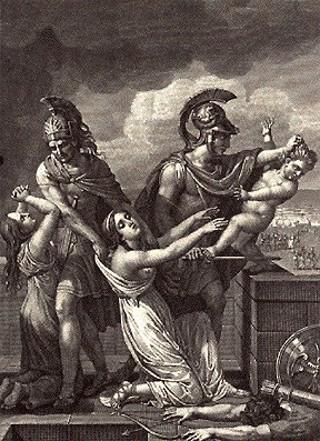

A scene from Euripides' classic play Trojan Women, which consists almost entirely of female characters and questions the ethics of the Peloponnesian War.

In 1976, Richard Dawkins coined the word “meme” as a concept for discussing the development and propagation of culture through a discussion of evolutionary principles. A meme, as defined by Dawkins, is “a noun that conveys the idea of a unit of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation” (Dawkins, pg 192). It is a building block of culture, a unit of culture that can be replicated and that is subject to the processes of variation, mutation, competition, and inheritance. It is the cultural equivalent of a gene.

As I’ve stated previously on Serendip, I can easily see the value of memes as an organizational tool. By breaking down expressions of culture into basic units, it becomes easier to track the development of current cultural forms. However, in Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, Daniel Dennett takes the analogy of memes to genes way too far. According to Dennett, the development of culture is, like biological evolution, an entirely algorithmic process, and memes are analogous to genes in that they mindlessly replicate, their variations and mutations based entirely on the principles of randomness.

I cannot see the value in taking meme theory this far. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: reducing the development of culture to a mindless, random algorithm drastically reduces the powerful influence of human agency on culture. Someone comes up with the idea for a cultural meme; others observe the meme and deem it “worth saving—or stealing or replicating” (Dennett, pg 142). While there may be randomness present in what sort of or whom inspiration strikes, or in the tastes of those saving or stealing or replicating the meme, it is still inescapably true that there is a human selector present in the development of culture. Unlike the algorithm of evolution, in which there is no active designer and no selector, culture has both a designer and a selector present in the human race.

To further explore and explain the impact of human design and selection on culture, I’d like to direct your attention to ancient Greek tragedy and why we study it today. Ancient Greek tragedy is a confusing, archaic form of theater. Its existence rests largely on paying tribute to a god no longer believed in; its form consists of lengthy, poetic monologues and various permutations on now-ancient mythology; and, strangest of all, one of its central features is the chorus, a body of people who sing or chant long, formal speeches in verse, which punctuate and elaborate on the text.

So why do we study this archaic form of theater today, if its composition and performance are so foreign to modern audiences? Dennett and Dawkins would say that studying ancient theater serves the practical purpose of understanding the development of theater and its memes. This, of course, is an excellent reason: you have to understand where you came from to understand where you are today. But what is it about Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides that makes them the best people to study and understand theater’s origins? Perhaps it’s because these men actively conceived of and revolutionized theater as we know it today.

Aeschylus, “the most innovative and imaginative of Greek dramatists” (Sommerstein, pg 36), was the first playwright to have two speaking characters on stage at once (Aristotle, via Sommerstein, pg160), and is known as the father of character-driven dramas as a whole. Sophocles introduced a third speaking character, pioneered a greater complexity of plot, and began highlighting character over traditional adherence to the original myth, creating the archetype of a “Sophoclean hero,” a character who sticks by their principles no matter what the consequences (Sommerstein, pg 45), a trope recognized in theater even today. Euripides invented the deus ex machina (Sommerstein, pg 55), and was one of the first to explore the psychological motivations of his characters and to utilize women and slaves as vital, intelligent members of the dramatic form. These writers, from their own imaginations, created theatrical forms that shaped the development of theater to come. Designers of their craft, revolutionaries in their field, their active contributions to this cultural form shaped the future of theater forever.

Even more literally, however, we study these tragic playwrights because they are the only ones available to us. Out of the other dozens of tragedians recorded, out of all of the other playwrights whose works triumphed in the City Dionysia, only these three have works extant today. Many might write this off to the natural randomness of the world. The other playwrights’ texts weren’t as well preserved, and so rotted away; their homes caught fire, and any plays were incinerated in the flames; a flood carried all the texts off all off. But it can’t just be coincidence that the three playwrights whose works happened to survive are the playwrights who won nine festivals between them, and garnered several secondary and tertiary awards (Sommerstein, pg 34-54). Nor can it be coincidence that the playwrights whose works survive had been “singled out as classics” as early as fourth-century BC by Hellenistic scholars, so that their texts were singled out in turn for archival preservation and widespread public performance (Sommerstein, pg 3).

The active human selection of these playwrights’ works led to their being available to us today. First their plays were literally selected as winners of specific festivals; then they were literally selected to be copied and preserved for future study. Furthermore, once they had been copied for public performance, these texts were selected by travelling theater troupes as staples within their repertoires and allowed to spread through Alexander the Great’s unification of Persia and Greece. As these texts were performed outside of Athens, other cultures were able to observe and modify theater, allowing for new forms of literature and theater to develop. It if hadn’t been for these human selectors, theater as we know it would never have developed, and we would not be able to study ancient theater today.

There cannot be culture without human designer and selectors. As we can see by studying ancient Greek theater, it is active human innovation that leads to the design and development of memes, and it is active human selection that allows for the proliferation of those memes. If Aeschylus had never thought to add a second character to the stage, we would never have the theatrical forms we have today. If Hellenistic scholars had never chosen the plays of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides to be copied for public performance, we would never be able to study ancient texts, and other cultures would never have been able to develop their own variations of theater. Dennett can argue all he wants about the algorithm of culture and the randomness of memes, but human agency in the development and proliferation of culture will always be a flaw in his “dangerous idea.”

Works Cited

Dawkins, Richard. The Selfish Gene. 2 ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. Print.

Dennett, Daniel. Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster,1995. Print.

Sommerstein, Alan H. Greek Drama and Dramatists. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Comments

Beyond the Binary?

ewashburn--

I love the punning quality of your title!...and am certainly drawn in by your image (but why that one? why lead w/ the death of a child??)

In my response to your last paper, I nudged you towards more open-ended forms of co-constructed dialogue than the "debate" on the argument of the origin that you and ckosarek had constructed. This time around you've chosen Daniel Dennett as your sparring partner, and my response is an echo of my earlier one: might you be interested in, and able to, play with different position? Not one that tries to "beat" or "silence" Dennett by nailing the "flaw in his dangerous idea"? But rather tries to accommodate both his insight and your own?

Your insight is right on, I think: that once active human conceivers, designers and selectors entered the random process that is evolution, they altered that process; their interventions changed outcomes. But there is of course a flaw in that good idea: it overstates the extent of human control, and the degree to which they were able to direct what happened.

Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripedes created new theatrical worlds "from their on imaginations," as you say, but they also drew on the imaginations of those who had gone before them. You describe them as revolutionaries (emphasizing a dramatic break w/ what had gone before); in the language your classmate cr88 used to described political change, these playwrights were evolutionary, building organically on the work that preceded theirs. Their texts were deliberately selected for archiving, but there were also some accidents along the way in that process (and so some of their texts were not preserved).

This is a great story you have to tell, a needed corrective and counter-narrative to Dennett's. Might you try, next month, to tell another good one that isn't founded, this time, in the debate structure of a binary opposition?