Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Web Event 2: Cripping High Schools in Inner Cities

I attended a public high school in the heart of Los Angeles’ inner city, a predominately black neighborhood, characterized by poverty, drugs, gang activity, and violence. This environment is similar to that of schools in many cities across the country, and I have felt some of the negative effects of a public school system operating on a normative standard that does not fully encompass their students’ multifaceted lives as a result of their low socioeconomic status.

During the school year, we were annually prepared for and given standardized tests, extensively pressured to perform and grade well, and were constantly ruled by and held to normative standards of time, space, and achievement advertised by the school’s mission statement to “prepare all students to attend and compete at the top 100 colleges and universities in the nation.” My school’s mission and intent, like many public schools in Los Angeles, assumes an intense pressure on performing, and assigns a normative time schedule to our lives if we were to take on the roll of being a high-performing student. In attendance at my school were students with multiple layers to their identity, students living in single-parent households, female students affected by teenage pregnancy, male students selling drugs as an alternate form of familial income, and other factors that can be seen as consequentially queering the normative scheduled timeline of a student’s high school years. A student’s home life does not cease to affect the student while they are at school, and often in schools like mine, certain effects of the intersectional identities of young, poor, black children growing up in America, make attending and completing high school extremely difficult.

I believe that these institutions can be remade to better encompass students with intersectional identities in a number of ways. Instead of subjecting students to higher standards than their socioeconomic status allows access for, high school curricula and environments could be adjusted to embrace and help guide students with intersectional identities. High schools in the inner city can be “cripped” by discontinuing the use of standardized testing, embracing the possibility of students not going to college right away, and by having guidance counseling services work in hand with administrators, faculty, and the student’s parents, to help readjust the students’ learning environments in an effort to better guide them, help them navigate their environments with more ease, and be flexible enough to encompass all the intersections of their lives.

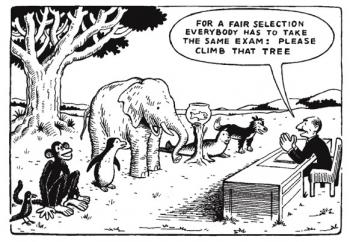

Firstly, I believe that the use of standardized testing in schools is one of the key normative processes that does not fully encompass a students’ intersectional identity. These tests are given with an overpowering focus on “achieving”, while inaccurately measuring the intelligence of students and don’t take into consideration the layers of their identity that may affect how they perform on these tests. Evident clearly in the title “standardized tests”, is an institutional process that assumes a “standard” of proficiency that every student of that age and grade, essentially unrealistic to achieve to students with multilayered identities.

The children who are most likely to perform adequately to the standards set in place are upperclass white students, and the children who are still left behind are not only poor students of color, but also students with mental and physical disabilities, and students who learned English as a second language. Assuming a “standard”, normative life that children live that holds them to the same standard of learning that not many students with intersectional identities can achieve. If I may be allowed to speak casually, I have experienced firsthand the pressures of standardized test taking, and throughout my high school career I was under the impression that no matter what I was going through outside of school, I was expected to show up and perform well on these exams. I understand the marginalizing affects of being compared to the highest performing students in the country, and constantly battled with feelings of inadequacy, deficiency and overall underachievement.

Next, I believe that giving students the chance to consider taking a year between high school and college would open up the possibilities of their lives. In these intensive academic environments, when students’ needs are not met that encompass the totality of their intersectional identities, the pressure to go to college grows so large that a student may either a) not see the importance or benefits of a college education, or b) not think a college education is obtainable because too much that goes on in their lives contributes to their difficulties in school. An option should be presented that encourages students to take a gap year between high school and college instead of going straight to college, which could resolve the issue of their being underprepared and overwhelmed, increasing the chances that they actually graduate college. Giving students a safe place to embrace deflections from the normative timeline that includes going to college would be incredibly helpful, and not considering these deflections as negative or limiting to the possibilities of their futures could ease the pressures as well.

In response to my proposal to discontinue the use of standardized tests, the question may arise of how to measure the students’ progress, and to that I reply, “Why do they need to be measured?” Why, as a measure of students learning and engaging with the world around them, do they need to be measured on a linear scale and placed aside their classmates in competition? Why is it that the only way to measure how much a student has learned is by their ability to fill out a Scantron? Do we equate being able to fill in boxes with answers to multiple choice questions with learning?

In response to my idea to encourage students to take time off before going to college, someone asked “Well, what would they do during their time off?”, which prompted me to stop and think. How can it be ensured that students who are taking time off actually go to college after the year? I thought here that it could be beneficial to have a group of educators or a program that helps guide these students through this as well. Weekly/ bi-weekly meetings could be held between high school graduates and these administrators to ensure that they are making the most of their time off, are keeping intellectually engaged, and plan to actually return to school when they find themselves in a situation where they would be prepared to compete and complete at the top 100 colleges and universities in the nation, essentially a prolonged “College Prep” program of sorts.

In conclusion, many things can be done to educational institutions in low-income neighborhoods, all placing each student in the center of his or her unique experience, one that is solely their own and not comparable to other students’ experiences. I, of course, am not claiming to have the solutions to education reform in low-income neighborhoods across the country, but a stake that I do have in my arguments is from the position of a student who feels that any one of my suggestions could have helped me better deal with the intersectionality of my identity.

Comments

I also talked about students

I also talked about students being reduced to the boxes they check on a form in my essay, although in a slightly different sense. I agree that every student should not be held up to one normative standard when their identities are so multifaceted and unique. I'm curious, though - how far would you like this change you propose to go? Would you stop with eliminating standardized testing? What about grades? Are you calling for a complete overhaul of the capitalist productivity-based system that puts us in school in the first place? When we were talking about crip time in class, it was mentioned that some people need competition and structure to thrive. Would you put them in a separate system and have them compete with each other? Your paper raises these and many other interesting questions that I'd be excited to have you answer.

In Class/Out Classed

vhiggins--

last month you were attempting to re-write the script of the female entertainer, and I was pushing you to be more explicit about the ways in which you think your education might give you a hand up with that project. This month, you are taking on that education directly @ the middle school and h.s. level, questioning the “intense pressure” it places on performing, as well as its use of a "normative time schedule.”

As I mentioned to several of your classmates, I taught an ESem a few years ago called InClass/OutClassed: On the Uses of a Liberal Education, which worked specifically with the (range of answers! to the) question of whether schools function primarily as sites of socialization and normalization, reinforcing the status quo, or whether they might be explicit sites of intervention, mobility and change.

You argue that schools in poor neighborhoods be “cripped”: “by discontinuing the use of standardized testing, embracing the possibility of students not going to college right away, and by having guidance counseling services work in hand with administrators, faculty, and the student’s parents, to help readjust the students’ learning environments in an effort to better guide them, help them navigate their environments with more ease, and be flexible enough to encompass all the intersections of their lives. “

In an (in)famous refutation of the sort of ‘cripping’ you advocate here, Lisa Delpit’s book, Other People’s Children, argues that poor children can’t afford to have their curricula queered or cripped (she doesn’t use these terms, but she’s talking about just the sort of adjustments you describe): they need too much to learn all the skills required in the mainstream. There is no leeway.

EmmaBE’s description of the Posse program is a great example of the sort of thing you imagine more abstractly; please read her paper, as well as that by EP, who is also raising questions about intersectionality and class difference, and y’all come to class ready to share ideas….