Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Duality of the Gaze: An Exploration of the Beauty and Shame Found Found in the Female Body

In 2009, I visited an art exhibition at the Austrian Cultural Forum New York, titled “The Seen and Hidden: [Dis]Covering the Veil.” The show created a clash of western and eastern cultures in order to display the controversial interpretations of what it means to be covered, objectified, and sexualized in the preconceived notions of Arabic and Islamic cultures. The pieces in the show invoked a vivid sense of both frustration and mockery at the overall confusion and misunderstanding found across the globe, which has ultimately resulted from the potent duality of the gaze.

Although I had long forgotten much of the show since 2009, there was once piece that has still strongly resonated with me because of its fascinating depiction of the two interpretations of body covering. The featured artist, Marlene Haring, has categorically confronted social norms in her works, often using blond hair as a motif to establish both a grotesque and luxurious presentation of covering. Because Every Hair is Different (shown left) shows a being covered head-to-toe in long, luscious, and glossy locks of hair; that is nonetheless unsettling. Haring draws emphasis on the culture and politics of female hair, and how it is both “a symbol of beauty and a point of shame” (Smith). We are conflicted by the simultaneous sense that we are staring at both animal-like nakedness and a completely conserved, hidden body. How can the subject be exposed and obscured at the same time? This almost irreconcilable pairing of thought can be applied more broadly to the understanding of appearance of any being, especially female.

The concept of covering female bodies, especially with the veiling of hair, carries this controversial duality in which there is seemingly no middle ground compromise. A woman who decides to veil is seen either as an oppressed female who is under the tyrannical control of her religious and/or political beliefs, or a proud, diligent citizen who carries good morals and is attuned to the powers of her body. How can it be that our bodies are both praised and scorned? The conflicting idea appears in the Qur’an, with specific regard to clothing as a means to “cover your shame as well as to be adornment to you” (Al-A Raf: 26). This verse is further explained in The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam and how “Allah warns people concerning both nakedness and neglect of good appearance” (77 Qaradawi). We are told to wear garments to protect our body but to also be weary of exposing our body through the same means. Can we be both clothed and naked at the same time?

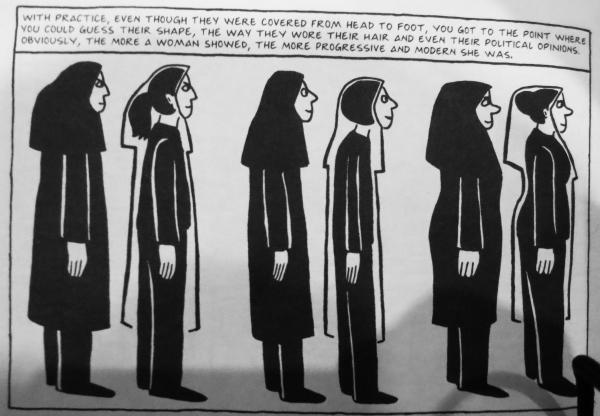

Marjane Satarpi’s The Complete Persepolis, openly questions the role and illusion that veiling plays during the Islamic Revolution if Iran in 1979. As a child, Satarpi expresses her dislike of being forced to wear the veil at school, simply because she did not understand why she had to. As a teenager living in Vienna, the veil symbolizes a lost cultural connection to her heritage and origins. And finally as young woman studying in Iran again, Satarpi vocalizes her frustration and ridicule of the veil’s restricting powers. She is able to “see right through” the façade of the veil, a thought that is illustrated in an excerpt from “The Convocation” (shown left).

In this illustration, Satrapi describes how “With practice, even though they were covered from head to foot, you got to the point where you could guess their shape, the way they wore their hair and even their political opinions. Obviously, the more a woman showed, the more progressive and modern she was” (294 Satrapi). Her ability to imagine the women’s bodies beneath their dressing represents her opinion on how ineffective the veils are at preventing the gaze of both men and women. In Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she stresses the idea that the male gaze and the female gaze are essentially the same because women look at themselves through the eyes of men (Sassatelli 127). The theory emphasizes the constant judgment of women through the gaze and Satarpi’s beliefs against the veil, as she is able to read each woman through their protective coverings.

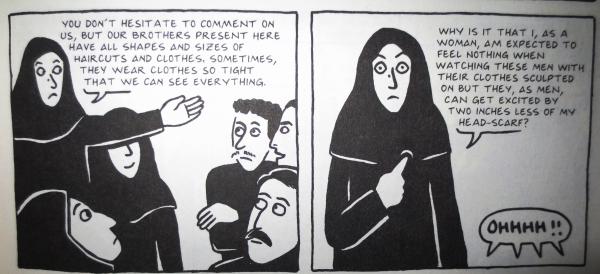

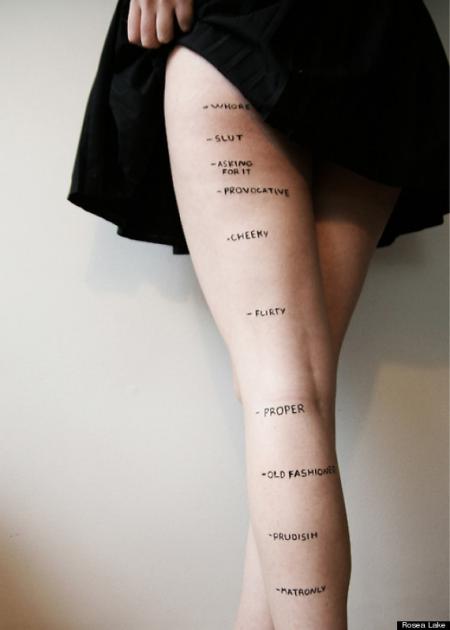

Again, in Persepolis we find the duality behind the gaze and whether or not a woman is considered exposed or covered based upon her physical presentation. Marjane Satrapi really questions the minor extent to which these interpretations can be interchanged, especially in comparison to men. “Why is it that I, as a woman, am expected to feel nothing when watching these men with their clothes sculpted on but they, as men, can get excited by two inches less of my head-scarf?” (Satrapi 297). In this illustration (shown above) the power of the female gaze upon males is clearly underestimated, which contributes to the inequality found in judgment upon women’s apparel. In a photo by Rosea Lake (shown below), aimed at reflecting how women are judged according to the length of their skirts, we observe a powerful visual of interpretations from a universal gaze. Once again, there is no medium of being properly concealed and revealed at the same time; we are either labeled with shame or beauty.

The works of Marlene Haring, Marjane Satrapi, Laura Mulvey, and Rosea Lake are just a few of many artists questioning the social interpretations of female presentation. There may never be a clear, universally accepted balance between conserving and revealing our bodies. Different cultures across the globe have only ambiguously defined what is to be considered beautiful and shameful. Most of us can agree that the human body seen at any state will always be interpreted either way, because there is no single, satisfactory conclusion.

Works Cited:

Haring, Marlene. Because Every Hair Is Different. 2005-2009. Photograph. Austrian Cultural Forum New York, New York City.

Lake, Rosea. Judgement. 2013. Photograph. Vancouver.

Mulvey, Laura. "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema." Screen Autumn (1975): 6-18. Print.

Sassatelli, Roberta. Interview with Laura Mulvey: Gender, Gaze and Technology in Film Culture. Theory, Culture & Society, September 2011, 28(5) p.127.

Satrapi, Marjane. The Complete Persepolis. New York: Pantheon, 2003. 294, 297. Print.

Smith, Anna FC. "Marlene Haring - Because Your Worth It." N.p., n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2013.

Qaraḍāwī, Yūsuf. The Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam = Al-Halal Wal-haram Fil Islam. Indianapolis, IN, USA: American Trust Publications, 1999. 77. Print.

Comments

revealing is concealing

pipermartz--

You’ve assembled a wonderful series of visual representations of your ideas (I, too, saw Haring’s work @ the Austrian Cultural Forum in NYC in 2009, w/ two of my daughters—one of whom inserted her own long blond hair into the performance/presentation:)

I think you are playing here w/ the very essence of the work Laura Swanson was highlighting in her series of anti-self-portratis: how every representation is always both a revealing and an uncovering. The decision of two of your classmates to change their usernames last week, in order to free themselves to speak more openly about questions of sexual orientation and object choice, is another clear case in point: more “veiled” (in terms of being identified) they can be more “exposed” (in terms of their ideas). Every representation both covers and uncovers, foregrounds some dimensions while leaving others in the background

Your paper is rich both visually and conceptually, though I think @ the end you retreat into a sort of generalized “conclusion” about the impossibility of a “clear, universally accepted balance between conserving and revealing.” The stronger statement would be that a representation is always partial, always bringing something to the fore @ the expense of something else (for a theoretical—and explictly culturally located-- exploration of this idea, see Paula Gunn Allen, Kochinnenako in Academe: Three Approaches to Interpreting a Keres Indian Tale ).

Haring draws emphasis on the

Haring draws emphasis on the culture and politics of female hair, and how it is both “a symbol of beauty and a point of shame” (Smith).

I love this.

I get really angry when people tell me that I have "good hair" or "I don't need a weave". These are not compliments to me. This language is coded. You are essentially saying "it's not nappy, or it's exotic". This is not anyone's place to say or impose the "American standard of beauty" on to me. I love my hair. I love how it can totally transform my outfit, my vibe, my attitude. I love its "duality": from curly fro to sleek and straight.

I say this because I think it relates to your discussion of the veil. As a western woman, I think that we are conditioned to think that women who cover are oppressed, weak, or "not-feminist" enough. This has always bothered me. Although there are many women who do not wear the veil by choice, who are we to impose our standards/norms/judgement on to another culture?