Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Watson: A Gendered Robot?

Creating a computer that can process natural language at an uncanny, if not human, speed is an unprecedented development with tremendous implications for the future of human-machine interactions. On Jeopardy!, February 14, 2011, IBM introduced their creation: Watson, a formidable question and answering machine designed to compete against the best jeopardy contestants. What makes jeopardy so fitting for the development of this technology is the game’s organization around natural language, which is replete with “intended meaning” (nytimes). Jeopardy! is filled with allusions and indirect metaphors which demand (human) interpretation each time contestants are presented with a clue. Because processing natural language is undoubtedly a human skill, Watson presents us with a machine that has taken on human characteristics. Among these human qualities are Watson’s ability to process natural language and his seeming identification as male (both in name and voice).

“Most people realize that fundamentally there's nothing going on inside the silicon except the cold calculation of ones and zeros.” (Garfinkle) Image Source: http://www.joblo.com/skynet-lives-watch-ibms-watson-crush-puny-humans-in-jeopardy

For me, there’s something about Watson’s presence on this game show that suggests more profound societal implications centering on notions of identity and placement within a “human” world. Watson, in actuality, is an amalgamation of hardware so extensive that it occupies an entire room in the lab. On Jeopardy!, however, Watson is nothing more than a male name, a male voice, and an abstract, gender-neutral avatar. What does this presentation, this identification of the computer on the game show, suggest about imposing identity markers (particularly gender) on the non-human? Why is Watson male? Why gender Watson at all? And, once gendered, why choose a gender neutral avatar to represent him?

![]()

Image source: http://www.astroman.com.pl/index.php?mod=magazine&a=read&id=864

Two articles, Schwartzman’s “Engendered Machines in Science Fiction Films” and Robertson’s “Gendering Humanoid Robots: Robo-Sexism in Japan”, provide compelling insights into this question of gendering the non-human, particularly, robots. Both authors provide a number of reasons as to why humans are often disposed to gender their technological creations, focusing specifically on issues of identity or identification (for the machine) and familiarity (for the humans). All of the insights are tied to the concept of enhancing the future of human-machine interactions, smoothing the robotic assimilation into modern culture. Schwartzman focuses particularly on gendering technology and machines so as to make them less alien to people and more familiar. Early in his article he begins by stating that the “human-like machine, [occupies] an unstable position somewhere between nature and artifice”. Here he suggests that robots occupy an uncanny position somewhere between that which is natural (and more associated with humans) and that which is artificial (merely a creation). The notion that a robot is not entirely artificial is implied by its position held somewhere in the middle of the continuum from natural to artificial. In this notion, Schwartzman already establishes the sense that robots are closer to what is natural, and human. Perhaps the acceptance of robots into society and our future necessitates a sense of familiarity with these alien machines. Although machines are not emotional, humans are. As Thomson suggests in his nytimes article “What is IBM’s Watson”, it is precisely Watson’s absence of emotion that gives him an edge—he is not subject to the nerves and anxiety which plague humans. Schwartzman’s statement at the beginning of his article introduces this notion that for humans to accept robots, they must be comfortable, their emotions—resistances to the unfamiliar and alien—must be taken into account when introducing robots into our society

Schwartzman argues: “popular concepts of robotics personify robots, and this personification implicates gender… Gender-related expectations infuse public expectations for robotics, with robots anthropomorphized to reflect and extend the gender-associated roles.” As these lines reinforce, in most popular culture references, robots are personified—most likely to appeal to the audience’s emotions, strengthening their ability to empathize with the robot characters—and as a result gender naturally comes into question as a fundamental aspect of personification, of personhood, in our culture. Particularly in literature and movies which are designed to appeal to emotion, the reader/viewer expects the robot to be anthropomorphized which includes a distinct display of gender. Schwartzman makes a fascinating point by suggesting that the motivation behind these expectations of gender roles is the cultural familiarity embedded in the gender roles themselves. He argues that “to make technological innovations less disruptive, the new technologies must meet user expectations associated with human interactions.” In addition to gender being a familiar aspect of people in our culture, gender is also implicated in interactions between humans; humans are familiar with interactions more or less with gendered individuals. Regardless of the gender (feminine, masculine, transgender etc.), people are used to gender as a defining characteristic of the individuals they interact with. In order to enhance the interactions between human and machines, Schwartzman suggests, many roboticists consider it important to gender their robots. “Gender markers” provide “an anchor for further interactions”; with the implication of gender, the alien qualities of the non-human become more familiar, more human.

Image source: http://uncannyvalley.net/book/export/html/203

In addition to implicating gender in robots in order to familiarize and humanize them, Robertson makes an interesting, related, argument for gender as a form of identification. She argues: “The process of gendering robots makes especially clear that gender belongs both to the order of the material body and to the social and discursive or semiotic systems within which bodies are embedded” (4). In this line she reinforces the argument discussed by Schwartzman: the notion that gender is something which is familiar in the presentation—particularly material—of an individual; the appearance of the individual marks its gender. However, in addition to this basic sense of gender as an identifying material characteristic, Robertson here introduces social and “semiotic” notions of gender. By “semiotic”, she introduces the notion of embedded meaning within the concept, the construct of one’s gender—the underlying meaning signified by the actual presentation. The meaningful aspect of gender identification is socially grounded in cultural understandings and conceptions of gender. In the line quoted above Robertson introduces the idea that in attributing gender to the non-human we can see the deeply embedded significance of gender as an identifying marker in the human world. Robertson suggests that “gender attribution is a process of reality construction”. Gender is part of the human need to construct meaning in order to anchor themselves to reality because gender acts as a marker, a signifier of identity, of placement within the wider world. The significance of gender in the construction of identity is clear precisely because of the roboticist’s compulsion to assign gender to their creations.

House wife robot; image source: http://www.cao.go.jp/innovation/innovation/point.html

Despite the fact that humans feel the need to anthropomorphize robots and other creations, in her article, Robertson suggests the disparity between gendered humans and gendered robots. Because robots “lack the actual physical genitals”, “these play no role in their initial gender assignment”, leading roboticists to defer to “cultural genitals” which are evoked through surface material factors (dresses, pants, pink, blue, etc). As a result she states that “the relationship between human bodies and genders is contingent. Whereas human female and male bodies are distinguished by a great deal of variability, humanoid robot bodies are effectively used as platforms for reducing the relationship between bodies and genders from a contingent relationship to a fixed and necessary one” (6) In this sense, although human gender-assignment may correspond with the corporeal features of the individual, Robertson acknowledges the “variability” present and the “contingency aspect” which may refer to the gender being contingent at times on the biological features of the individual, but also contingent on the personal choice of the individual. With robots, on the other hand, their gender is “fixed” because they are created in the image of a certain gender and have no biological features with which to correspond with that gender. This leads to less variability because the body of a robot is its gender.

The following chart which Robertson cites is a fascinating portrayal of objects which vary in their “human likeness” and the corresponding levels of “familiarity” they produce in humans. The designer plots two lines, one showing the level of familiarity produced across objects which move, and the level of familiarity produced across the objects which are still.

Image source: http://www.cnet.com.au/i/r/2006/Games/uncannyvalley1_422x330.jpg

The uncanny valley shows the eerie, negatively associated things, “corpse”, “zombie” and “prosthetic hand”. The moving “zombie” is by far the least familiar (having the greatest negative familiarity), in this sense the most “uncanny”, eerie, even frightening (if just fictitious) of the objects. The most familiar and human-like is the moving “healthy person”. The moving humanoid robot is marked as being about half as familiar as the healthy person and 50% human-like. The corpse is regarded as about 60% human-like, yet has a negative familiarity. The prosthetic hand appears to be plotted in both its moving and still state. Interestingly, the moving prosthetic hand has a slightly less human-likeness and a greater negative familiarity than the still moving hand. This graph is interesting in its evocation of various objects which have human-like characteristics and the corresponding emotional familiarity levels produced in humans. This graph suggests that generally the more human-like something is, the greater the familiarity (barring the “uncanny valley”, which is identified as “uncanny”, and thus wholly unfamiliar despite its supposed human-likeness), which reinforces the sense that the more human-like a robot is, gender included, the more familiar it will appear to humans. Although, it is important to remember that their artificiality in and of itself marks them as significantly less human-like, cautioning, in my opinion, against a too-humanized robot.

Robertson’s most insightful analysis in this article lies in her discussion of how human robots should look. There is undoubtedly a very unsettling quality to robots which resemble humans too much, as their artificiality is almost exacerbated by this eerie likeness. On the other hand, as much of the article has made clear, the humanization of robots increases familiarity, comfort, and ultimately human acceptance of these creations. The question remains to be answered: just how human should robots be? In her discussion of one roboticist, Mori, Robertson states that “a thing, such as a prosthetic hand, that looks real but lacks the feel and temperature of a ‘living hand’ creates a sense of the uncanny or sudden unfamiliarity” (17).In this sense because the hand looks so real, yet does not feel real, its artificiality is exacerbated and the individual is even more uncomfortable and resistant to this foreign appendage. Robertson reflects that Mori argues: the “metallic and synthetic properties of robots” should be retained in design “so as to avoid the creepiness factor and forestall any cognitive-emotional confusion among humans” (18). In this sense, many roboticists argue for a balance between human and artificial robot design: human-like enough to foster familiarity and comfort, yet artificial enough to avoid the eerie and uncanny which would produce negative emotions.

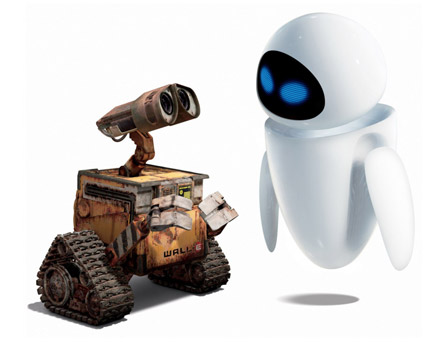

After considering the various factors that influence the decision to engender robots, I have found that in general, like the articles show, the presentation of robots in fiction and in the real world has centered around normative conceptions of gender: male and female. Perhaps a more familiar representation of robots would be that portrayal which is variable in terms of gender. Below I have included two images the one on the left is of Wall-e and Eve from the Disney Pixar movie “Wall-e”, which presents its viewers with a normative, hetero-sexual love between two gendered male and female robots. The image on the right is from a posting for “Object-ifying Gender—Art Installation Project” on The Freire Project where an artist has created an image of a robot challenging gender norms.

Image source: http://www.artsjournal.com/popcorn/2009/04/the_eyes_have_it.html

Non-normative robot (shopping for princesses and batman) image source: http://freireproject.org/blogs/object-ifying-gender-art-installation-project

It remains unclear to me why exactly Watson is gendered, but I suspect it was for the very reasons Schwartzman and Robertson discussed. Making Watson gendered male—at least in name and voice—makes him more accessible to the contestants and the viewers. Yet, curiously he is represented by a gender-neutral avatar of the “smarter planet” logo of IBM. The most visual representation of Watson, therefore, is not gendered suggesting an interesting attention to non-humanizing the machine in appearance. Watson’s identity is not entirely male or female, is not entirely gendered, but is first and foremost a super-computer represented visually as an abstract picture of a “smarter planet”. Ultimately, I think this design decision makes Watson, though male in name and voice, appear more universal and accessible with larger aims towards advancing technology and human-machine interactions.

Works Cited:

Jennifer Robertson. “Gendering Humanoid Robots: Robo-Sexism in Japan”. Body and Society. 16.2 (2010): 1-36. Web. 3 Mar. 2010. <http://sitemaker.umich.edu/jennifer.robertson/files/gendering_robots_-_robosexism_b_s_6-2010.pdf>

Schwartzman, Roy. “Engendered Machines in Science Fiction Films”. Studies in Popular Culture 22.1 (1999): Web. 3 Mar. 2010. <http://pcasacas.org/SiPC/22.1/schwartzman.html >

Simson, Garfinkel. “Robot Sex”. Technology Review.(2004): 1-2. Web. 3 Mar. 2010. <http://www.technologyreview.com/computing/13604/>

Comments

"The uncanny valley"

vgaffney--

you've twined together here two very interesting and complementary arguments. The first has to do w/ the gendering of robots--the use of "gender markers" that enable humans to interact more comfortably with machines. But the second has to do w/ the intriguing reverse activity--the caution against creating robots that are "too-humanized," and so "unsettling" to humans (according to the theory that we feel revulsion when robots too closely resemble us, the "uncanny valley" is a negative dip in the graph reflecting our reaction).

The first point allows you to demonstrate nicely the deeply embedded significance of gender as an identifying marker in the human world. Where I'd really be interested to hear you speculate further would be about the implications of your second claim: might they have to do with the deep significance we attach (shades of Haraway!) to the distinction between the human and the artificial worlds? Why do we resist making it more "leaky"?

Anyhow, you go on to demonstrate quite nicely how this uneasy balance was achieved in the creation of Watson, who was "gendered male" in name and voice, but represented in a form that was visually abstract, as the icon of a “smarter planet."

I want to thank you, finally, for accepting my challenge to make your paper more web-friendly, by incorporating images to illustrate your argument. I'd like to keep nudging you in that direction--your "citations" aren't seamless yet (I can't always quite figure out what "work" each image is intended to perform in the paper), and of course there are multiple ways in which you might think of forms, alternative to the conventional paper, for presenting your ideas. Spend some time browsing in the Electronic Literature Collection for inspiration! Perhaps the "uncanny" quality of some of these projects will invite you to work towards a paper that is less recognizable as a "paper"? More uncannily...

"not" a paper, but.....what?? And what might be the pay-off, for going off-grid and into that valley??