Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Perils of Passing as Explored by the Works of Frances Negrón-Muntaner and Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez

In order to explore the intra-action of queerness and Puerto Rican-ness I have chosen to focus on two pivotal queer cultural productions by Puerto Ricans. The first is the 1995 film by Frances Negrón-Muntaner, Brincando el charco: Portrait of a Puerto Rican. The second is a poetic excerpt from Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez’ play Side Effects. These texts address many critical questions that intersect both querness and Puerto Rican-ness. Among these, the theme of passing, essential to both texts, particularly necessitates the interaction of queerness and Puerto Rican-ness. Passing is so critical to immigration and queer studies that the editors of the anthology on sexuality and immigration in which critical analyses of both of these texts appear, chose the title Passing Lines. In the introduction they argue that passing “can implicitly question not only the solidity of ethno-racial lines but of sexual lines as well” (Epps 5). I believe the Negrón-Muntaner film and the Sandoval-Sánchez play, as well as their authors' mediations on their respective works, illustrate through passing just how inter- and intra-connected queerness is with Puerto Rican-ness.

Images of "brincando el charco"

Brincando el charco

1. To hop over the pond

-Brincando (verb) is the gerund form of the verb brincar, which means to hop.

-El charco (masculine noun) means the puddle.

2. A colloquial expression that refers to migrating from the Caribbean to the continental United States

3. The 1995 film by Frances Negrón-Muntaner

4. An album created in Cuba with Cuban, American and Chilean artists that, according to their website, is dedicated to confronting “Racism, Homophobia, Sexism, the US embargo, Inequality, and much, much more”

Negrón-Muntaner’s film presently remains relevant and generative as an essential revisionary text, 16 years after its initial release. Brincando at once revises the existing image of Puerto Rican women in film while simultaneously filling an immense void within Puerto Rican queer cinema. Negrón-Muntaner explains that “when [she] began work on Brincando el charco, no Puerto Rican film had addressed lesbian subjectivity in one hundred years of cinematic production” (Muntaner 521). Not only did this void impact her decision to create the film in the first place, but she also directly sites it for influencing specific decisions within the piece itself. For example, Brincando initially did not explicitly depict or allude to any lesbian sex, but rather had only one on-screen kiss. Ultimately, Negrón-Muntaner added an overtly sexual sequence that she hopes challenges the portrayals of lesbian sex mass-produced in pornography. She chooses to interrupt the explicit scenes with intertitles stating “don’t look” and “¿qué miras?” to highlight the voyeuristic and objectifying glances of the viewers (Muntaner 521).

The film’s title Brincando el charco is not only a reference to a popular Puerto Rican saying to refer to migration to the mainland, but is also reflected in the content of the film. The protagonist, Claudia Marín, situates many of her current experiences with a transnational sentiment towards her birthplace and the island where she grew up, Puerto Rico. We see the protagonist watching footage of the LGBT pride parade in Puerto Rico as well as a flashback to the circumstances leading to her exile. The mise-en-scene of the flashback is full of iconic catholic imagery, including a looming statue of the Virgin Mary, in a living room that otherwise looks like any house from a television set. The images of the statue are interrupted as Claudia’s father, deep voice booming, confronts his daughter of suspected lesbianism and kicks her out of the house. Negrón-Muntaner intended this scene to be a parody of Puerto Rican melodrama, although she quickly found that on a whole audiences did not read the scene as parodic but rather realistic and many viewers expressed feeling a deep connection with the scene (Muntaner 517). Both the parodic and realistic readings of the scene, highlight another revisionary goal of the film. Negrón-Muntaner explains that it was to function as a critique of “the purging of all women from the nationalist phallic imagination over the last 150 years of writing the nation. The nationalist scribes have represented the nation as a family--the sacred Puerto Rican family--steering past obstacles as long as the captain of the ship is a capable, well-to-do, white Puerto Rican male” (Muntaner 516). By questioning the necessity of a patriarchal figure to guide the family, and ultimately, the nation, Negrón-Muntaner problematizes assumptions of race, gender, sexuality and power.

The film explores questions of passing in experiences related to gender, queerness, nationality and language of both Claudia and her girlfriend, Ana Hernández. In an interview Ana does for Claudia she explains how she feels she feels insufficiently white in the United States and insufficiently Puerto Rican on the island, in other words, she is unable to pass in either context. Ana explains that in order to feel more comfortable she rejects attempts to pass in favor of “playing up” her New York identity in the presence of “real” Puerto Ricans and her Puerto Rican identity when in the presence of “gringos” (Brincando). Muntaner addresses this question of being Puerto Rican enough in the context of visibility and identity in terms of Claudia as well. She explains that Claudia, as a light-skinned woman, must always be “mediated” through the bodies of dark-skinned Puerto Ricans, and even other people of color, because within the metropolitan culture they “signify Puerto Rican visibility and colonized identity” (Muntaner 515). She achieves this in the film by intertwining images of African pride parades as well as Claudia’s professional interest in dark-skinned homosexual Puerto Ricans. Many would classify Claudia’s position as “priveledged” because, unlike Ana or darker-skinned Puerto Ricans, Claudia “can escape the daily indignities of being a racialized minority and claim to be “Spanish”” (Muntaner 515). However, Negrón-Muntaner is quick to explain that although Claudia as a blanquita can pass, it is “often to places to which she has no interest in going” (Muntaner 515) or it is at the necessary exclusion and denial of her heritage.

Every time the fictional Claudia interacts with others who do not know her background, she is able to be perceived as something else because of the lightness of her skin. Often an uncontrollable factor like skin color is met with behavioral factors that help facilitate or at times impede passing. In the Introduction to Passing Lines the editors define passing lines as “the performative acts by which a person passes, or strives to pass, as conforming to certain norms of identity and behavior” (Epps 4). Although her skin color is a physical characteristic, her ability to speak unaccented English and her potential choice to do so, for example, could be read as a performative act of passing.

Alberto Sandoval-Sánchez tackles many of his own critical questions of passing in relation to his identity as an out homosexual Puerto Rican man with AIDS. He argues in his article, “Politicizing Abjection: Towards the Articulation of a Latino AIDS Queer Identity,” that abjection is the central characteristic of Latino queer bodies with AIDS. Rather than fighting against this characterization, Sandoval-Sánchez himself has embraced the ability to “materialize and enact abjection as a strategic performance in which identity is always in the making” (Sánchez 318). Rather than try to pass as a “healthy” body in the way that the norm defines it, principally HIV-negative, he hopes that “queer Latino/a cultural performances materialized a discursive site of and for abjection that menaces the homogeneity and stability of official hegemonic culture and identity and its anxieties that keep the queer, the AIDS survivor, the Latino/a migrant, the racial and ethnic other locked in its place” (Sánchez 318). Although never explicitly stated in such terms, Sandoval-Sánchez’s argument is clearly against passing and the homogenic culture he believes it fosters and supports.

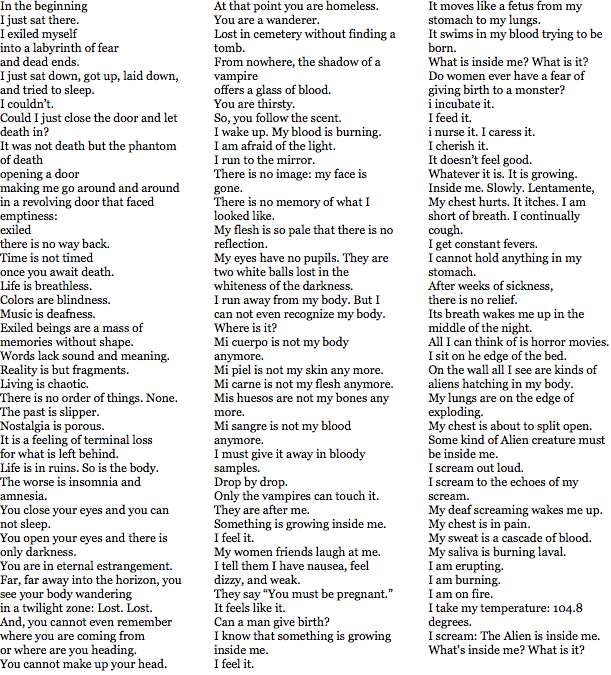

Sandoval-Sánchez’s stern unwillingness to attempt to pass as healthy, or happy, or pain free, is clear in the following excerpt from his play Side Effects, which was staged originally 18 years ago at Mount Holyoke College:

Sandoval-Sánchez is steadfast in his dedication to representing his abjection. He even compares it to the umbilical cord “to my migrancy, to my mariconería, and to my Latinidad” (Sánchez 316). In doing so he refuses to reproduce AIDS-related tropes that the audience may be more comfortable with, of a white upper-class male who overcomes his HIV to achieve certain accolades, perhaps. Although I am sure important at the time, I would argue his dedication to representing his abjection and the stark style of the piece is even more important today in contemporary America. From a public health standpoint there has been a shift in the way AIDS is framed from a dire life-threatening illness to a less threatening disease, much like diabetes. This shift ignores important issues of race, class, access to health care and medical literacy that would make a life with AIDS, or diabetes, for that matter, as easy as depicted and it has resulted in decreased funding and attention to domestic AIDS projects and research.

Brincando and the excerpt from Side Effects as two cultural productions from queer Puerto Rican individuals both successfully problematize and fight against passing and its many potentially silencing effects. The texts, and the critical commentary by their authors, demonstrate clearly the concept stated by Linda Schlossberg, an editor of a book on passing, in her quote in the Introduction to Passing Lines. Schlossberg outlines the vast range of possible experiences associated with passing. She argues that “passing can be experienced as a source of radical pleasure or intense danger; it can function as a badge of shame or a source of pride. Passing as practice questions the assumption that visibility is necessarily positive, pleasurable, even desirable” (Epps 5). A critique of passing, like Brincando and Side Effects, not only fights against the assumed desirability of visibility, as suggested by the Schlossberg quote, but also the perils of conformity along lines of race, sexuality, health, etc. I wonder, however, if, given the current political and economic climate, Sandoval-Sánchez’s hope for the rejection of passing and the acceptance of abjection is just a fantasy. If the immigration climate of the United States continues to favor bodies that conform and attempt to pass (with the notable exception of the queer asylum laws), then won’t the intention to pass prevail?

Works Cited:

Brincando el charco: Portrait of a Puerto Rican. Dir. Frances Negrón-Muntaner. Perf.

Frances Negrón-Muntaner. Independent Television Service, 1995. DVD.

Negrón-Muntaner, Frances. "When I Was a Puerto Rican Lesbian: Meditations on

Brincando el charco: Portrait of a Puerto Rican." GLQ 5.4 (1999): 511-26. Web.

"Introduction." Introduction. Passing Lines: Sexuality and Immigration. Ed. Brad

Epps, Keja Valens, and Bill Johnson González. London: Harvard University,

2005. 3-50. Print.

Sandoval-Sánchez, Alberto. “Politicizing Abjection: Towards the Articulation of a Latino

AIDS Queer Identity.” Passing Lines: Sexuality and Immigration. Ed. Brad

Epps, Keja Valens, and Bill Johnson González. London: Harvard University,

2005. 311-320. Print.

Slideshow Images:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_k-i7-6weYso/TPakBZq_gKI/AAAAAAAAAJU/eRr7cpPxhgg/s400/1puddle.jpg

http://click.si.edu/images/upload/Images/md_2887_Image_5sibsJumping.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_4XFK93QZya8/TMReySxwbpI/AAAAAAAABoE/gu8GlzXS9MA/s1600/shutterstock_397439.jpg

http://newsimg.bbc.co.uk/media/images/45418000/jpg/_45418567_jump_ap466.jpg

Comments

Response to Anne's Comments/Reflection on Web Event 1

I made the conscious decision while writing to choose our class as my primary audience. I used words such as intra-action that we directly discussed in class, as well as a some terms (like abjection, for example) that assumes a background in gender/sexuality studies, just as our class does. This paper assumes an English speaking (ideally with a little knowledge of Spanish, to best understand the excerpt from Side Effects), moderately-versed in Gender and Sexuality studies, internet savvy audience. I knew that this paper would be posted online, but I decided the many potential barriers to understanding, including language, most notably, would mean that that potential readers could self-select if this piece were of interest and appropriate for them rather than changing my writing approach preemptively to make it more accessible to a larger internet population. Furthermore, one who might be more likely to encounter this piece online (through a google search, or through serendip browsing) might already be interested in such topics and could be technologically savvy enough to follow the links I posted within the piece and/or potentially do their own searching to better understand terms they did not understand.

I do think it is interesting, however, to talk about what “motivates” my paper, as you suggest. I am not used to including this in academic works and in this less-formal/more public context there is definitely more space for it. The discussion that follows about my user-name, avatar and relationship to the topic should be informative about why I chose to write about this topic.

I do not think my user-name gives much of a clue to my “authority to speak about these matters.” My user-name refers to the “inorganic structure” that I came up with to describe myself on the first day of class. My assumption is that most of the class remembers/assumes this was the inspiration for the user-name, and I have gotten into conversations with many classmates to further explain why it stuck (that I consider myself a good facilitator of discussion and I believe one of my strengths as a facilitator is to encourage conversation with seemingly different individuals or groups of individuals by highlighting what they share in common and subsequently in what they differ to spark conversation, like a venn diagram). As for the general internet population who has access to the source, I am now sure what they will assume about the choice venn diagram, but if they did a quick search of wikipedia and/or dictionary.com I would be satisfied with their understanding of the concept.

As for my avatar, a photo of my own face, there may be more implications/assumptions made about my ability to speak/write about this topic. This photo shows a young, smiling person. My guess is that my race, white, and gender, female, most often could be accurately assumed from the photo, although these characteristics have never been explicitly stated thus far in any of my blog postings. If one did not already know that I was writing this as part of a college level course, the fact that I appear young could provide information to the reader. I think that my age/educational standing is actually the most important marker towards my “authority to speak about these matters.” As a senior at one of America’s “top” liberal arts colleges I feel confident in my ability to write a coherent, well-argued academic paper. As a Spanish major and a Gender and Sexuality Studies minor, I feel further prepared to talk about many of the issues in this paper, as I have taken many college level courses that involve similar subjects over the last three years. Although the evidence of my “authority” is largely academic, rather than personal, for example, I think based on the context that is sufficiently appropriate, even the title of my piece evokes traditional academic writing.

My primary relationship to the topic is the academic one I just outlined. I also, however, have a professional interest in immigration rights. During high school I worked for two summers as an assistant teacher to the ESL class for the Project Reach Youth: Even Start program in Brooklyn, NY. The program provides ESL classes to young immigrant mothers while their young children are attend pre-school. I made incredible connections and friendships with the women, mainly immigrants from Mexico. Additionaly, more recently I have been pursuing jobs in public health and the last two summers I have worked for the Clinical Directors Network, an organization in New York City that “puts research into practice” and both conducts field public health reserach and directs educational seminars for health providers across the nation. I worked on their CenteringPregnancy research project, which aims to prove that group prenatal care for adolescent teenagers leads to better birth outcomes. Many of our participants speak Spanish and are either first- or second-generation immigrants.

As for your concerns about the end of my paper, where I wonder if the type of change proposed by Francés-Muntaner and Sánchez-Sandoval is “just a fantasy” and I question the usefulness of thinking in terms of presently unattainable goals. You say that you “want to resist” this sort of questioning and give the example of activists who try to “imagine peace.” I want to contextualize and defend my line of thinking here, though, because I find it to be one of the parts of the piece that most honestly and truly reflects my opinions. My questioning reflects my fear that academia can get lost in the theoretical and lose sight of the pragmatic. Although I can get much intellectual pleasure out of academic conversations that I would consider more “theoretical,” I feel more comfortable when I ground myself in more pragmatic goals. For example, upon graduation I will pursue a career in public health (rather than higher education in gen/sex studies), where I will work directly on projects like the CenteringPregnancy project and will see more immediate improvements in the lives of individuals. Within the themes of this paper, a suggestion that would be more inline with my preferences would be the sorts of policy reform that make immigration discrimination based on HIV status or sexual orientation, for example, illegal, rather than an ideological shift away from “favoring bodies that conform.” Ideally this would not be an either/or situation. I would love to also strive for such an ideological shift, but with the primary attention given to on on-the-ground improvements.

Passing

venn diagram--

So, please s-l-o-w down a bit to begin, remembering that you are writing, on-line, to an audience who doesn't know what "intra-action" signifies, or what we've said, so far, about "passing" as a key trope in our studies, or why you might want to explore either the "intra-action of queerness and Puero Rican-ness," or the critical role that "passing" plays in such intra-actions. What, in short, motivates your paper? What is your relation to the topic you are exploring? Why should I/we/the web audience pause to hear what you might have to say? (Along these lines: what do your user-name and avatar signal about your authority to speak about these matters?) I'd like to see, in short, a much clearer framing and setting up….as well as a much clearer "getting out of"

…the VERY interesting work that you perform here. What I like first, is the way in which you take the concept of passing into another, related realm, which we haven't really explored in this course: that of queer immigration rights and action. There's much here to linger over and think about: what enables an audience to read scenes as "realistic" rather than "parodic" (hm…another form of literary "passing"?). What has enabled us to shift our framing of AIDS "from a dire life-threatening illness to a less threatening disease," to "pass" (!?) as something "much like diabetes"?

What I like, next, is the central substitution here of "playing up" for "passing" --by a woman who finds herself "insufficiently white" in one context," "insufficiently Puerto Rican" in another, and so "unable to pass in either context." This offers a striking challenge to the sorts of conformity "to certain norms of identity and behavior" that passing reinforces, to what you call the "homogenic culture it fosters and supports." "A critique of passing fights against the assumed desirability of visibility [and] the perils of conformity." Passing "to places where one has no interest in going" challenges the hegemony of normalcy, offers the possibility of alternative sites of being and doing. Wow to all of that.

"Passing," in your analysis, seems to presume stable identities, one able to "cover" for another. So what I really like most here is the way in which the challenges to passing that you document call attention to the ways "in which identity is always in the making," not a fixed category to be occupied, to cover over another, but always problematizable, in process, negotiable.

You end this rich analysis, though, by questioning its usefulness in a way I want to resist. This is not "just a fantasy" (peace-workers sometimes begin their conventions by the act of "imagining peace"--if you can't imagine it, you can't work towards it…), but an alternative way of thinking about identities and how we police them. How might what you call the U.S. "immigration climate" shift away from "favoring bodies that conform"? How might some of what we have learned in this course be useful here? (Remember Kaye's discussion, in week 5, about the implications of our "multi-modal sensory perceptions" for "the complexities of passing," for the ways in which we process the information we use to categorize people/events or to make judgments?) "What information do we let pass?"