Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Persepolis: Confronting the Limits of Expression and Representation

The style of Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis is striking in that it is so bare, composed solely of black and white images and somewhat caricatured in its simple portrayal of events and individuals. Satrapi employs a purposeful minimalism and understatement in her approach to graphic narrative. This approach emphasizes the degree to which much of the horror and alienation she experienced as a result of growing up in an oppressive and war-torn society cannot be expressed or represented in any form. Instead, the reader is brought into a stark world of black and white that implies what cannot be fully communicated visually or textually.

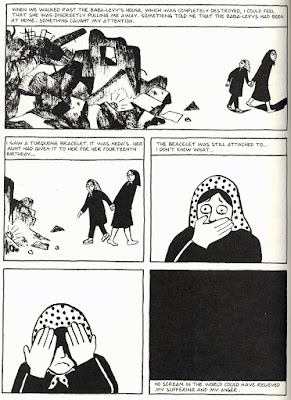

This reduction of a life into frames of black and white is a method of radically deconstructing an incomprehensible, and often traumatic, whole. In telling her story, Satrapi uses the form of graphic narrative to create artificial sequences, which in the graphic narrative's generic use of the gutter between frames suggests the unarticulated void between experience and expression, intention and interpretation. In one of the more horrific events that Satrapi depicts, a bombing near her home that kills her neighbors, the black and white frames, along with the gaps between them, serve to convey the horrifically untranslatable:

In this sequence, Marji views the total destruction precipitated by the bombing, and in a shocking reminder of the life that has so gruesomely perished, she views a bracelet amidst the rubble that belonged to a girl whose life has now been snuffed out. In the bottom right frame, the final in the sequence depicting the event, the space is displayed only as pure black, and underneath Satrapi writes, "No scream in the world could have relieved my suffering and my anger" (142). This portrayal of blackness and the juxtaposition of her statement of inexpressible pain and rage are jarring in their refusal to submit to conventional modes of representation and their assertion of the rawness of such extreme, obliterating experience. In this case, it is the lack of detail in language and picture that so immediately conveys the psychological impact, and disintegrating force, of the experience.

In a similar way, Satrapi employs an understated approach in portraying other acts of political violence, in particular the executions of dissidents. Repeatedly throughout the graphic narrative, Satrapi portrays executed dissidents or killed soldiers as anonymous, interchangeable forms. This is partly a reflection on how violence, whether military or political (or both) effectively strips a person of their agency, negating their identity and often their life. In depicting political dissidents who were executed, Satrapi writes: "Those who opposed the regime were systematically arrested...And executed together" (117). She depicts the dissidents as strangely lacking in identity, their expressions inscrutable, as they are lined up to be killed. Their anonymity, conveyed in their uniformly composed bodies and faces, highlights how the government's oppressive tactics and disregard for life reduces their humanity, making each person indistinguishable from the next, as they are executed according to the inhuman prescriptions of ideology.

Also notable is how Satrapi interweaves a sequence of her own life as a juxtaposition to her imaginings of these executions. In frames above and below the portrayal of dissidents being executed, Satrapi also displays her own childhood act of "rebellion"--smoking a cigarette. There is something deeply ironic as well as perhaps honestly human in this depiction. One could view this juxtaposition as a form of self-reflexive irony, in which Satrapi looks back on her youthful rebellion as both inconsequential and naïve beside the horrors taking place around her. There is also a degree to which her younger self's attempt to embrace the forbidden, in whatever limited form, acts as an escape and a way to assume agency by distancing herself from the oppression and tragedy that could otherwise consumer her.

This use of irony also highlights Satrapi's often subversive use of humor throughout Persepolis to both distance and make accessible her most difficult experiences. As she writes, "We can only feel sorry for ourselves when our misfortunes are still supportable...once this limit is crossed, the only way to bear the unbearable is to laugh at it" (266). Laughter acts both as a coping mechanism and as a method of undermining authority: the authority of pain, trauma, and politics to dictate one's life and perspective. Satrapi's use of irony throughout the graphic narrative makes the often serious and horrific aspects of her childhood and adolescence take on a transformed, empowering, meaning.

From the first page of the visual text, Satrapi is already inviting the reader into an ironically drawn world of her experience, provided to us more convincingly from the perspective of the child witness who embodies the capacity for playful interpretation. In the opening page of Persepolis, Satrapi describes how in Iran in 1980, it became obligatory to wear the veil at school. She writes: "We didn't really like to wear the veil, especially since we didn't understand why we had to" (3). In the same frame, she displays herself and her classmates using the veil to play all sorts of games. Thus the children are displayed subverting authority due to the fact that the new rules and regulations being imposed by the government don't make sense to them. The children's disobedience is made humorous in that on the surface their actions seem so benign, and yet Satrapi is in fact making a political statement against the dictates of the state through the children's playful non-conformity.

Satrapi's use of minimalism and the distancing effects of humor throughout Persepolis draw attention to the limits of expression and representation, in particular when dealing with subjects of horror and suffering that defy full comprehension. It is precisely what is left out, both textually and visually in Persepolis, that invites the reader to enter into the immense abyss where expression falters. When confronted with the radical inability to verbalize and visualize experience, humor and irony act as devices that simultaneously acknowledge and subvert dominant discourses, and allow an individual to retain a sense of agency when circumstances and the fragility of our own finite existence threaten to tear our tenuous hold on survival.

Work Cited

Marjane Satrapi. The Complete Persepolis. New York: Random House, Inc. 2004.

Comments

"An ironically drawn world"

Yes, yes, and yes: it is, as you say, "precisely what is left out, both textually and visually in Persepolis, that invites the reader to enter into the immense abyss where expression falters." But it is also precisely what is put in: humor and irony, "devices that simultaneously acknowledge and subvert dominant discourses." It's Satrapi's minimal, endistancing form of articulation in the "unarticulated void," which both accentuates her fragilty and allows her "to retain a sense of agency."

When Northrop Frye (classically) described "satire and irony" as one of his "five modes of fiction," he characterized it by a hero who is "lacking power and intelligence"; with "effective action" being "absent, disorganized or foredoomed to defeat"; where "confusion and anarchy reign." But there are of course lots of other ways to think about how humor functions, and you think of some of them here.

On the one hand, I'd say that to employ irony, one needs some distance, has to be able to stand outside, "beside," and look across (as Anthony Appiah said when he spoke @ BMC a few years ago, "Ironism isn't for homebodies"). So satire might be enabled by being positioned on the outside/on the edge/in a place of relative powerlessness? Or @ least from being performed as if from that place?

I have some more thoughts about the relation of humor to politics. Some possibilities: