Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Presenting: Memory

Presenting: Memory

“We can call a book that emphasizes the who over the what—the shown over the summed, the found over the known, the recent over the historical, the emotional over the reasoned—a memoir.” –Larson, Memoir and the Memoirist. “A discovery which then becomes the story.”

If, as Larson states (a memoirist and critic), the “memoir today has the energy of a literary movement, recalling past artistic revolutions that initiated new ways of seeing” Satrapi has displayed a very literal new way of seeing with her graphic novel Persepolis (Larson 21). But how much does Persepolis diverge from or revolutionize (maybe even evolutionize?) the memoir? Most important in such a discussion would be Satrapi’s use of visuals: the graphics in her graphic novel. How do they ‘use and abuse’ the memoir’s identity? Each section of quotes provides an introduction to the memoir as it is pertinent to Satrapi’s work, and pages from her graphic have been included for reference.

The autobiography, the memoir, and Satrapi: Known for “singular themes” and “emotional immediacy,” the memoir developed from the autobiography and personal essays (Larson 15). Larson describes the attributes of a memoir as writing with “a modicum of summary and great swaths of narrative, scenic and historical, to sustain their singular theme or emotional arc” (Larson 17). “In memoir, how we have lived with ourselves teeter-totters with how we have lived with others—not only people, but cultures, ideas, politics, religions, history, and more” (Larson 23). So, the memoir is emotional, immediate, but also a chronicle of what makes and connects the rememberer to their past. Significance to the broader themes of the story matter. This holds true for both of Satrapi’s memoir-graphic novels, as her emotional memories interact and are connected with larger political events in Iran.

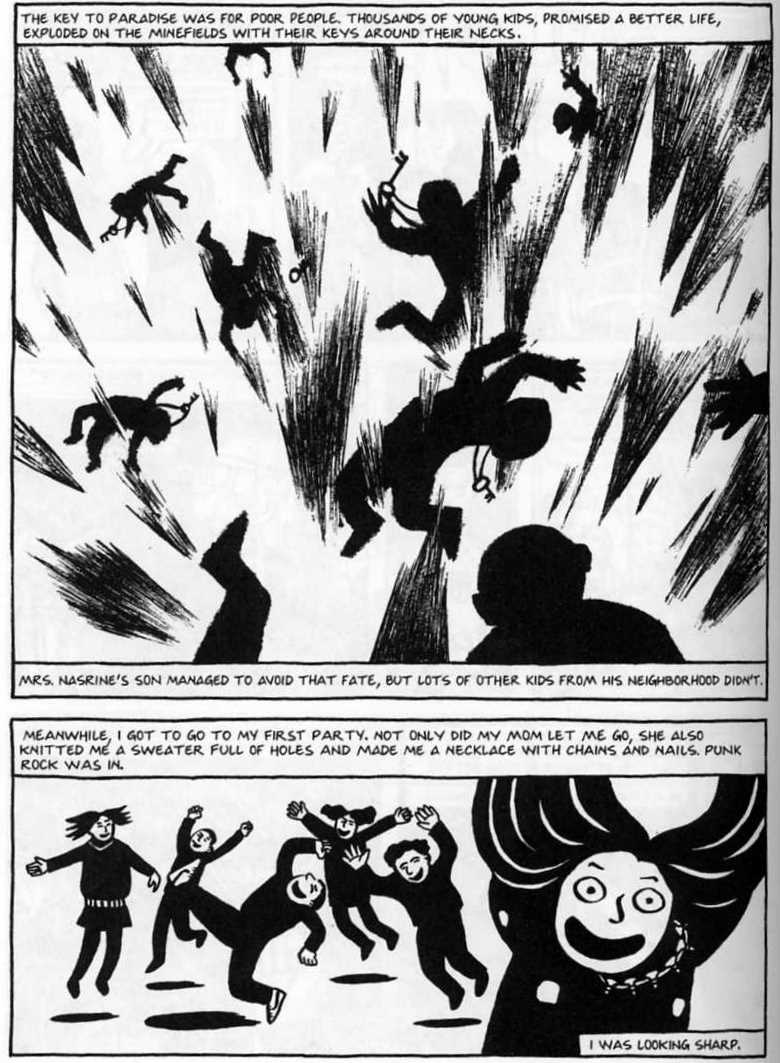

On page 102 of Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood Satrapi uses her graphics to display this emotion and significance to the reader. While the top frame holds a terrifying explosion of light, and young bodies are being flung into empty space, the bottom frame holds Marjane’s ecstatic face, enjoying her first party. We see Marjane’s youthful happiness and emotions that come directly from this period of Satrapi’s life. But we also see the greater political significance of Marjane’s life, brought to us by the rememberer, Satrapi –this is the theme of her graphic novels, the irony, the terror, the life, the knowledge and growth. In one page, Satrapi has used her graphics to create a visual of the memoir.

Presenting Memories and Remembering Emotions: “The construction of a relative self in the memoir is no less difficult [than that of the absolute self of the autobiography]: the person writing now is inseparable form the person the writer in remembering then. The goal is to disclose what the author is discovering about these persons” (Larson 20). “What many memoirists of the past twenty years have discovered… is how much the intervention of the rememberer, the person writing now, is pertinent to the work” (Larson 33). “The memoirist… cannot help but mix his consciousness today with the child’s. And yet the memoirist must not let the child know what the memoirist knows, even though the competitive awareness of a self then and a self now is what makes conscious writing about childhood so dynamic” (Larson 58).

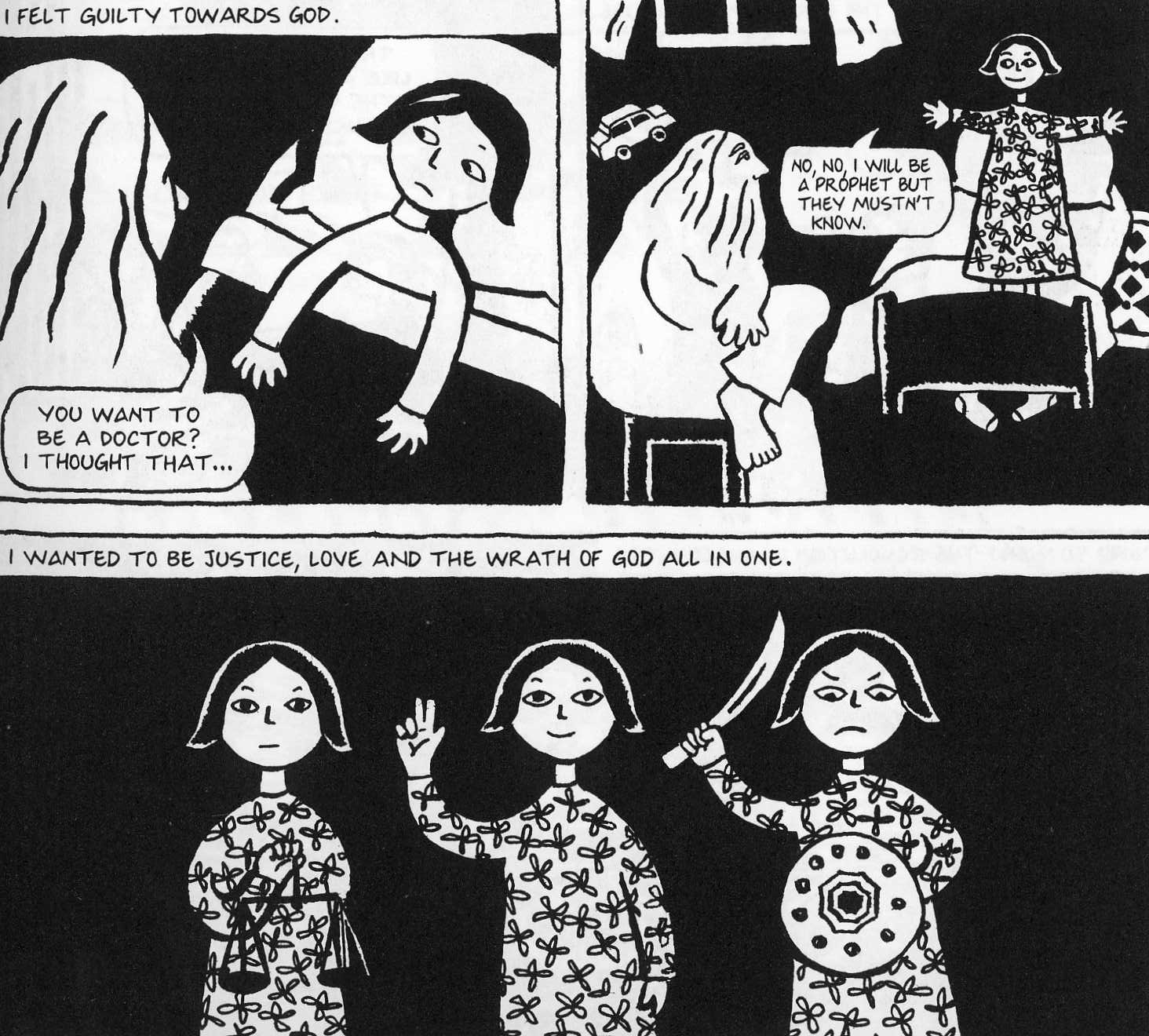

How Satrapi presents the ‘three selfs’ of her life (Marjane the child, Marjane the teenager and adult, and Satrapi the artist and memorist) with graphics is especially intriguing. On page 9 of Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood Satrapi depicts her childhood dream of becoming a prophet. With captions she presents the thoughts of Satrapi, the artist and memoirist, looking back in past tense. With thought bubbles and speech bubbles Satrapi presents the thoughts and actions of her younger self, Marjane. These thought bubbles and speech bubbles present even more layers, giving Marjane her thoughts, which differ from her actions: she thinks and dreams of becoming a prophet, but tells her parents she wants to be a doctor; captions display her feelings of guilt as she tells God how much she wants to be his prophet. These layers are what memoirs are defined by, and also what Satrapi’s graphics help to illustrate (literally).

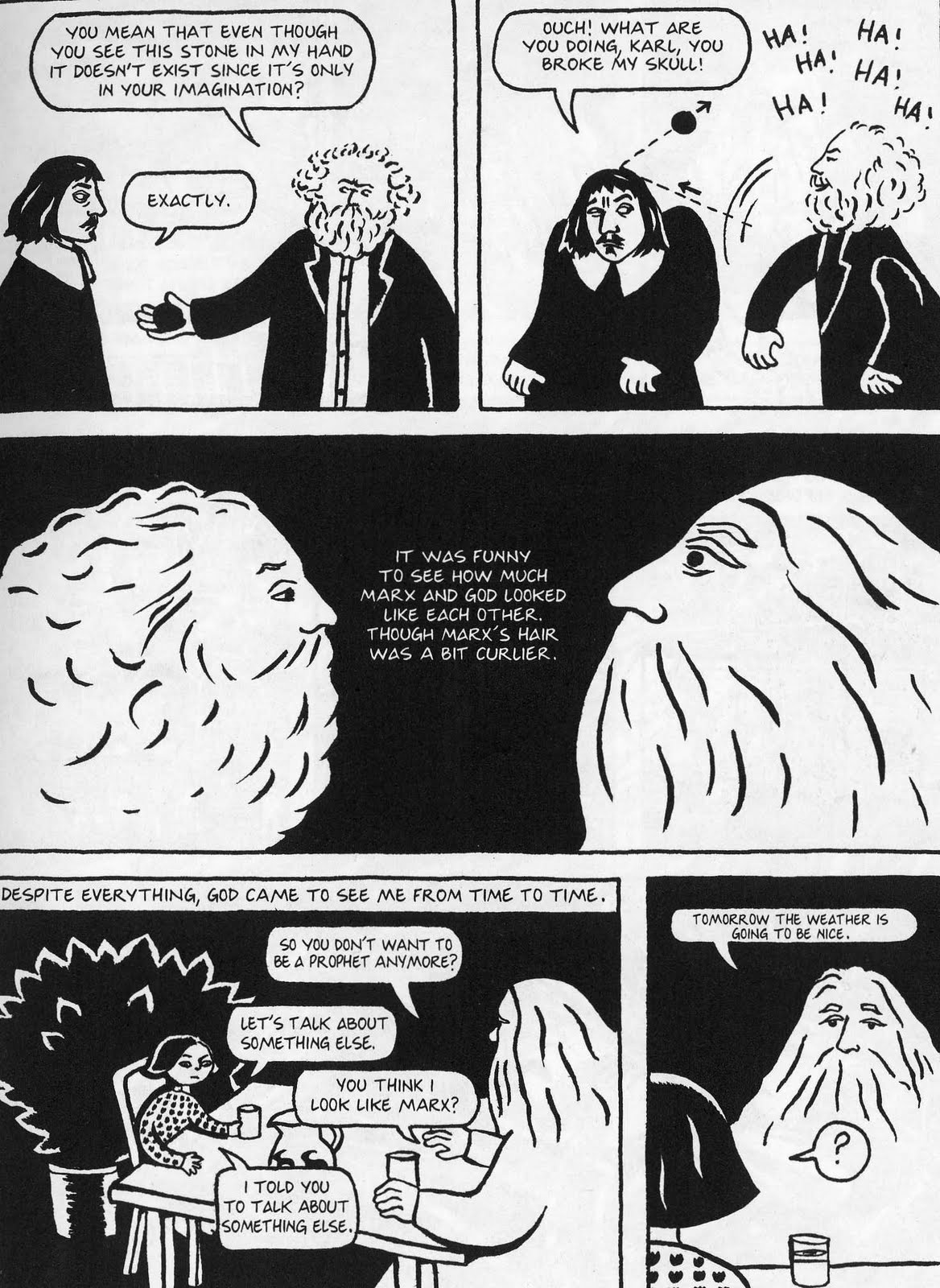

How we know Satrapi: “What is faced and lost is crucial. Only by lingering on something outside the self, with which he has had intimate experience, can the author disclose himself” (Larson 22). So Satrapi gives her life to us in short stories and vignettes, through which we see her growth, and the development of the world around her. We see Satrapi and her world through her relationships with friends and lovers in Europe and with Reza in Iran, with her family, and her politics at various times in her life. Her growth is depicted through what she believes in. In this way she follows the form of the written memoir, with only a few dimensions added through the graphics. These dimensions include the visual representation of the shaping forces of her life, an example of which is how she pictures God. However, Satrapi does not push boundaries as much with this facet of the memoir.

Remembered-Fiction: “Memoir is related to fiction because memoir, like fiction, is a narrative art: we narrate past events; always, as we write, memory tells us stories” (Larson 25). And yet, Sven Birkerts (another critic and memoirist) points out that “what gives the memoir its special title… is the constraint of the actual” (Birkerts 20). We see both of these definitions in Satrapi’s work, presented side by side to give us a fantastically realistic picture of her young life. Fantastical –God is presented interacting with Marjane in her childhood on page 13 of Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood. Realistic –the politics are presented, although sometimes simplified through the lens of a young child, with chilling detail (for example, pages 100-103 from Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood). This combination of the fantastical and the realistic give Satrapi’s work the depth that is required for the subjects she tackles, and make her graphics work hard to encompass the world she creates. Would this combination of fantastical and realistic be possible without Satrapi’s graphics?

Satrapi’s graphic novels are memoirs in their emotional content, their significance, and their presentation of her layered life. With her graphics she creates visual components of form and content seen usually in prose, but now broadened. But what does this mean? Perhaps that media are falling into each other further than we imagined –when literary criticism meant for prose memoirs stands up to evaluation through a graphic-prose form (with examples that are purely graphic).

Works Consulted:

Sven Birkerts. The Art of Time in Memoir: Then, Again. Saint Paul, Minnesota: Graywolf Press, 2008.

Thomas Larson. Memoir and the Memoirist: Reading and Writing Personal Narrative. Athens, Ohio: Swallow Press, 2007. http://site.ebrary.com/lib/brynmawr/Doc?id=10214177&ppg=25

Marjane Satrapi. Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood. Paris: L’Association, 2003.

Marjane Satrapi. Persepolis 2: The Story of a Return. Paris: L’Association, 2003.

Comments

Teeter-totter

rmeyers--

my new word, this weekend, is "intermediality"; it comes from a summary essay on the field of adaptation studies, which traces the "pervasive legacy that haunts adaptation studies: both the assumption that the primary context within which adaptations are to be studied is literature," and "the notion that adaptations ought to be faithful to their ostensible sourcetexts."

The bottom line of this review essay is that theorists of adaptation should look "more closely at the ways adaptations play with their sourcetexts instead of merely aping or analyzing them," and so replace questions about appropriation and adaptation with "intermediality."

I share this word w/ you because I think it entirely applicable to your discussion here of what happens when the memoir "goes visual," combining "the fantastical and the realistic" in what might seem @ first a "teeter-totter," but which, when done well, can provide a new depth to a well-worn form:

"Perhaps media are falling into each other further than we imagined –when literary criticism meant for prose memoirs stands up to evaluation through a graphic-prose form (with examples that are purely graphic)," and "Satrapi’s graphics help to illustrate (literally)" what a memoir is up to. As you observe, she gives us "the shown over the summed," in "great swaths of scenic narrative," and "uses her graphics to create a visual of the memoir."

In that light, I'd like to hear a little bit more about how you organized this paper. You explain that "each section of quotes provides an introduction to the memoir as it is pertinent to Satrapi’s work, and pages from her graphic have been included for reference," but such a structure has a fitful quality to it, as if there were frames (or @ least gutters!) separating one section from another. Were you trying to mirror Satrapi's form in your own? (See Shayna's powerpoint on Framing Our World: The Form of the Graphic Narrative for another very striking example of this.)

There's much more about memoir--and a deep questioning of its conventional attachment to "reality"-- in David Shields's Reality Hunger, should you want to bite...