Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Are Feminist Allowed to be Funny?

What's Feminism?

Feminism was never something I thought much about. It wasn't a prominent issue until I came to Bryn Mawr. After a semester here, I felt that I needed to get rid of my naive notion that feminism was a two sided coin. It wasn't one way or another, feminist or not. I wanted a more personal definition as to what feminism was and where I fit in the scheme of things which is why I decided to take this course. Critical Feminist Issues is the first course I've taken that is specifically about feminism. My experience with this class have been paradoxical thus far. More questions are raised than answered and the lines of feminism are getting blurred and yet I still feel like I'm getting a better idea as to where I fit into feminism and developing my own definition.

First Reactions to Three Guineas

When we were first given the assignment to read Three Guineas, my first reaction was "….I have to read a whole book?" My second reaction while reading it was, "Damn…she's really dishing it out." When I read "scarcely a human being in the course of history has fallen to a woman's rifle" (page 6), I was almost taken aback by her bold, snarky (as I had described in class) writing style. The whole explanation of the four teachers on page 97 sounded like a direct attack on men. It was as if Woolfe wrote out the antithesis of what men stereotypically stood for or did and went on to encourage women to follow this anti-example. The book as a whole felt like a bunch of burns and scathing disses written into beautiful prose. And I had to stop myself and think "Wait….Is this supposed to be funny?" Which led to a big question: Are feminist allowed to be funny?

A Definition of Feminist Humor

Asking myself if feminist were allowed to be funny led to the question of "what is feminist humor?" The only feminist humor that I have encountered is through Liz Lemon and Leslie Knope. But they were just characters on TV shows. I was always under the impression that feminist humor was either nonexistent or very dark and dripping with macabre twists. Leonore Tiefer, in her essay The Capacity for outrage: Feminism, Humor, and Sex, defines it a little more clearly. She says that "Feminist humor is political humor...Feminist humor subverts sexism and patriarchy by legitimizing women's concerns and deflating anti-women positions…[it] serves…as both an attack weapon and a unifier of the group."

Styles of Feminist Humor

Just like any other kind of humor, there are different styles of feminist humor. Brenda D. Frink describes the three main types in her article The feminist walks into a bar: Using humor to change the world: illumination, inversion, impersonation. "Illumination uses humor to highlight a hidden truth" Frink uses Sally Swain's book Great Housewives of Art as an example. In Swain's book, she takes famous painting and adds cleaning appliances in a "tribute to the artists' wives." Inversion "swaps traditional male and female roles in order to point out the injustice of current social attitudes and policies." This is the type of humor that Woolfe uses throughout Three Guineas. It is ironic when she describes in detail how men dress on pages 23-28. These observations as to how men dress is usually associated with how women dress. Impersonation is the satirical use of the voice of "the person who holds attitudes you want your reader to reject."

Some examples of feminist humor:

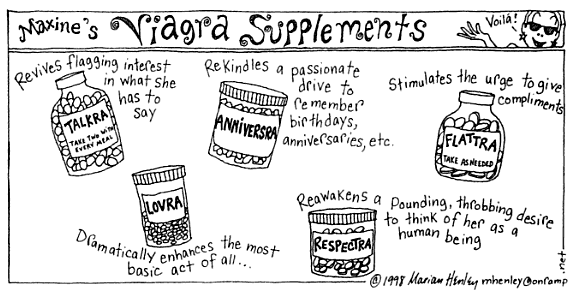

"Maxine's Viagra Supplements," published in Ms. October/Novermber 1999. Maxine!Comix

In this comic, it comments on how "Many women are apoplectic over the utipoian messages in Viagra marketing that imply that the little blue pill's likely side effects are romance, love, and tender passion..." A large portion of feminist humor has to do with men, but as seen in this comic, it also discusses sex as well.

"What would happen, for instances, if suddenly, magically, men could menstruate and women could not? Men wuld brag about how long and how much. Boys would mark the onset of menses, that longed-for proof of manhood, with religious rituals...Congress would fund a National Institute of Dysmenorrhea...Sanitary supplies would be federally funded and free [although] some men would still pay for presige brands...Military men...would cite menstruation...as proof that only men could serve in the Army ("you have to give blood to take blood")...Men would convince women that intercourse was more pleasurable at 'that time of the month'"

This is an excerpt from Gloria Steinem's essay in Ms. magazine, If Men could Menstruate. Steinem is commenting on the negative stigma associated with menstruation in women and how if men menstruated it wouldn't have the negative stigma. Tiefer also points out "Steinem's satire specifically pinpoints many of the ways that women are generally oppressed."

Humor as a Medium of Change

Tiefer makes a clear distinction between women's humor and feminist humor. Women's humor is described as humor that "lacks social awareness or social purpose." However, when humor is done correctly, I think it can make a point stronger. Tiefer points out that "Humor is a form of power, of resistance against oppression..." I like to think of it as empowering humor, humor with a plan. As seen in the two examples above, the humor is not the main focus but not a back player either. It is a vehicle used by both Maxine and Steinem to bring real issues into discussion and thought. Humor can also make things much approachable not as threatening. Feminist are often stereotyped as "femi-nazis" or harpy women with sharp tongues. Humor makes the topic approachable easily accessible. Lisa Donnelly a feminist cartoonist, says "quietly draw them in with a laugh." To break down hard concepts and make them lighthearted and easier to discuss. If topics are always serious, it can easily become very tiring and, at least from what I've seen, a touchy subject. For feminism to reach the realm of small talk, humor is the way to go.

There is also the unifying factor that Tiefer highlighted. For a movement to have a strong impact, it needs to appear together and there's something about laughing over the same thing that just brings people together. While it is not the main factor that unifies feminism (that would be a little sad…You're funny. I will therefor join your cause"), I do think the mollifying effect of humor can also benefit the champions of feminism as well. Sometimes it's good to take a break and just laugh.

So Why Didn't I Find it Funny?

I have a couple thoughts as to why I didn't find Three Guineas that funny. (Disclaimer: I know Three Guineas perhaps wasn't meant to be a humorous piece, but in my mind Woolfe seemed to be teetering the line of satirical and serious and I've always thought of satire as a form of humor.) First, there is the very obvious generation gap. Woolfe's got a couple generations on me so what I find funny and what she finds funny may not ever really cross paths. So it's obviously harder for me to relate with her '30s generation humor.

I also think there is a stylistic difference. Her humor seems more like dry, british humor. British humor has always been described to me as making fun of someone to their face without them knowing. The letter format of the Three Guineas made it seem like Woolfe was speaking with the recipient, a man, in front of a crowd of women. So in this case, the man is the one being made fun of. I could see how it could have been funny but it wasn't exactly resonating with me. This could have just been me and my own sense of humor but there was also the issue of class difference.

Many have pointed out the exclusive nature of Three Guineas and that it seems to be catered to a certain class of women: "the daughters of educated men" (page 6) But if her humor is working for this class isn't it fulfilling it's humor criteria? Tiefer says in her essay, "There's nothing as bonding to movement partisans as sharing the laughter or recognition and outrage with one's comrade." In the case of Woolfe, her audience was upper class educated women who could understand the references she makes when ridiculing the men in the suits and badges, who could empathize with the satire she uses when addressing the issues of asking a woman a question on war, and who could be comfortable with the idea of making oneself poor. While I may not have understood some of the "jokes" perhaps women of her time and class were quietly chuckling as they read. In the end, isn't a big portion of humor making fun of who isn't in the room? By that definition, humor can be a bit of a closed room situation. In the case of Virginia Woolfe, it is a very small room but, nonetheless, it is filled with people. So in Woolfe's defense, she's made (and maybe still making) someone laugh.

Comments

"Humor with a plan"

michelle--

you were one of the few members of the class who attended to the way in which Woolf wrote, rather than only to what she said. I think doing so has led you into an interesting, and insightful, exploration of the possibilities of feminist humor, into the ways in which it can bring a group together, make its cause palatable to others, AND function as a sharp means of resistance to oppression.

All good, very good.

But I think where this analysis gets tricky--and needs to go deeper--is @ the very end of your essay, where you observe that Three Guineas is not just "snarky," but "exclusive." To what degree is humor always exclusive, dependent on a shared set of norms, a shutting-out of those who are made fun of, an attack on those who are different? What you celebrate (Tiefer celebrating) as "bonding" --the "sharing of laughter, recognition and outrage with comrades"--inevitably has an outside: those who don't share, whose exclusion is precisely what we are laughing AT.

As you ask, in conclusion (though I think it's precisely this question that makes your paper inconclusive, and so productive for further thinking!) "isn't a big portion of humor making fun of who isn't in the room? By that definition, humor can be a bit of a closed room situation."

And closed rooms…? Well, they just don't seem very feminist to me...

Thank you for your comment

Thank you for your comment Anne!

I agree I could have gone further at the end about whether or not Woolfe's essay can qualify as humor since it does not have the unifying effect that Tiefer wrote about. It opens up a very large area of grey...since it could go either way...

It'd be really convenient if feminists had a humor board/council.