Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

What's That Word For When You Have To Break It To Find It?

“Change. Change. Change. Change…change. Change. Chaaange. When you say words a lot they don’t mean anything. Or maybe they don’t mean anything anyway, and we just think they do.” -Delirium

" Fish live next to the bodies of dead pirates."- Kathy Acker

Since our discussion of Persepolis as a story of a young woman attempting to find her own identity among great destruction and trauma, and our subsequent discussions of feminism in relation to graphic narratives, I’ve been stuck on the idea that Neil Gaiman’s Sandman character Delirium might be a nice counterpart to Marjane Satrapi. Delirium, one of seven characters who are the embodiment of earthy concepts, is, like Satrapi, a child trying to find her way in the world. Also like Satrapi, she is the product of some great trauma, though this trauma is never quite defined. However, the resemblance ends there.

If Persepolis offers us a gray scale world in which one searches for constancy and agency, Delirium’s story offers us a colorful swirl of de-contextualized suffering, out of which comes an utter lack of definition and identity. There is no constancy in Delirium’s world, as she is the embodiment of delirium as a concept. Though much of her back story is never revealed, and Neil Gaiman himself refuses to answer any direct questions about it, there are a few things that are known about her.

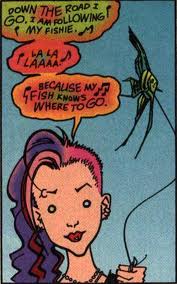

In the Sandman comic, she is the sister of six other Endless, or human concepts embodied in godlike forms; Dream, Death, Desire, Destiny, Despair, and Destruction. It is revealed early in the series that Delirium was once Delight, but that she changed into Delirium as the result of some great, as yet untold, trauma. Delirium’s realm is the realm of confusion, madness, unhinged language, bright abstractions, and an ever shifting outer appearance that sometimes even takes the form of a school of fish. She often speaks in nonsensical phrases and disjointed riddles, which later turn out to be the most insightful dialog in the book, and she is constantly searching for something, only she can almost never remember what, or even that she is searching.

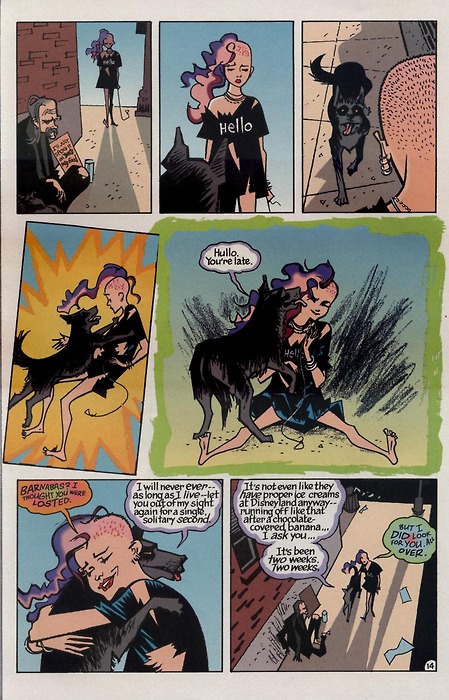

In her most prominent storyline, in Brief Lives, Delirium has remembered that her favorite brother, Destruction, has gone missing. She can’t remember when, and she can’t clearly articulate it, but she remembers that she forgot where he has gone. She somehow manages to convince another brother, Dream, to go searching for Destruction with her. Throughout the story, Delirium often forgets that she is searching but remembers that she is missing something or someone. She and her brother travel through the “real” world, even spending a night in a cheap motel with a cab driver while Dream attempts to figure out where Destruction is hiding. As Delirium alternately searches and forgets and remembers and forgets to remember and remembers to forget, they eventually find their Brother, where he has retired from his post, since humans have done a great job of destroying themselves, and taken up creative pursuits like cooking and painting while living in a cabin with his talking dog Barnabus. When they finally find Destruction, readers not only get a sense of Delirium’s sadness, but they also get a brief glimpse of her as Delight, in the form of a statue in Destruction’s garden. Eventually, Dream and Delirium must part ways with Destruction, but he gives Barnabus to Delirium and he becomes her companion for the rest of the books.

Though I had originally thought of Delirium as a bizarre counterpart to Satrapi, in the sense that while Satrapi’s story is centered in her journey away from and in spite of destruction, while Delirium can only find any peace if she finds Destruction, I kept getting stuck on Delirium’s language. When I brought it up in a writing conference and learned that Delirium was based on real life literary theorist Kathy Acker, I was delighted.

In her piece, “Seeing Gender’, Acker tells of her own search for de-constructed identity through her childhood desire to become a pirate, and her crushing understanding that such a thing was not possible for a girl. She tells of her own retreat into the world of books, where she could stop being a girl and begin being a “nothing”. She uses the story of Alice in Wonderland, and its internal poem The Jabberwocky, to show how a simple word choice can queer an entire narrative about who is allowed to have great adventures, and then asks her readers to consider the possibility that these word choices are also what creates people.

If we look at Delirium as the product of words, beyond the fact that she is a literary character, she begins to loom large as a potential peer to Stein with her de-contextualized language, and even Bihn, with his careful examination of salt, in the sense that, by never making sense, Delirium is free to exist as she sees fit when she sees fit. With Acker’s help then, what initially reads as Delirium’s suffering at her own lack of identity and ability to communicate can be read as the reader’s sadness at having to identify. We are not driven to delirium as a result of our own inability to make sense to others, but rather we are driven to madness by others’ inability allow us to stop making sense.

Acker uses this idea as a way to deconstruct gender. If words make us, she says, then words also make gender, and perhaps disabusing them of their certainty is the only way out of the gender trap. Though I am not sure how this could be accomplished in the actual world, the idea, in contrast to Stein’s “Lifting Belly”, is exhilarating to me, or maybe I’m exhilarating to it? Regardless, perhaps, like Delirium, the key to our collective peace could be finding destruction.

Comments

Thank you

Thanks for share!

Perfect

I think the comic is perfect.

Best,

Valorizing mental illness?

SYaeger--

when we last left off talking, I was asking you some questions about re-writing the canon of feminist graphic narratives:

What comics should we be looking @, to contextualize what Satrapi has done in terms of including women in comics? "What counts as canon worthy literature"? What texts "break the tropes of the genre," in ways that are worth our studying them? What else do we need to read, in order "to imagine a future for the comic genre that includes strong female characters in mainstream superhero settings"? In order to bring "an even broader scope of voices" (and body forms?) into academic settings?

Although you don't reference this conversation explicitly here, it seems to me that this new web event you've created is one response to that range of questions, a rich and exciting response. I like very much your contrasting Gaiman's rich swirl of colors with Satrapi's greyscale narrative, as two alternative renditions of trauma.

Your central claim is in line with much of the post-identity politics now circulating among queer theorists [check out, in this regard, an essay by one of your classmates that is also troubling the notions of fixed identity and ideology: just speak nearby/working towards ideas]. Your focus is on the suffering created by the need to identify as some concrete THING: "by never making sense, Delirium is free to exist as she sees fit when she sees fit….We are not driven to delirium as a result of our own inability to make sense to others, but rather we are driven to madness by others’ inability allow us to stop making sense."

This seems to me profound.

And also to raise another profound question--perhaps best articulated (for me) in Keith Doubt's 1996 "Towards a Sociology of Schizophrenia: Humanistic Reflections," a critique of post-modernism's tendency to valorize the mentally ill (in particular, to use schizophrenia as a metaphor for the human condition). Doubt (a striking name, in this context!) constructs his critique by using the terms of George Herbert Mead (Mind, Self and Society, 1934): "me" is the attitudes of others, which oneself assumes; "I" is "what we cannot tell in advance," that which "gives the sense of freedom, of initiative," is "never entirely calculable." According to Mead, it is the "social process" of these two distinguishable phrases ("conscious responsibility" and "something novel in experience") which constitutes the self. When the "me" co-opts the "I," it's a tragedy (shades of Hamlet?); when the "me" can't cut or tie "I," it's a comedy. Whatever the genre, it is the synthesis/reflexiveness/dialectic between the two which make up the grounds of identity and self-development. And valorizing mental illness is not (in this Doubt's view) the way to go.

What do you, and Delirium, and Kathy Acker, have to say about those apples? fish? dead pirates?