Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Queering Weakness: The Refusal of Strong Female Characters

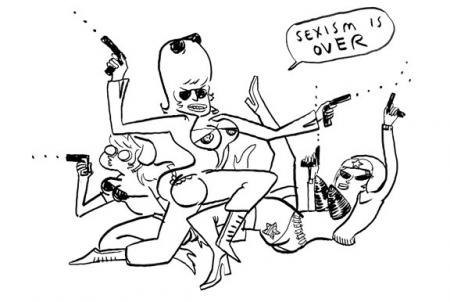

Kate Beaton, creator of the webcomic “Hark! A Vagrant”, in collaboration with two other cartoonists, Meredith Gran and Carly Monardo, created a small series of comics called “Strong Female Characters”. In the author’s notes on her site, Beaton comments:

“We are professionals in the entertainment industry and we think we know what we are talking about when we say that there needs to be more strong female characters out there and we know just what to do about it. Finally, some women to look up to!”

In her New York Times article from July of 2011, "Tough, Cold, Terse, Taciturn and Prone to Not Saying Goodbye When They Hang Up the Phone," Carina Chocano argues that the this idea of “strength” in the 21st-century fills the function that “virtue” has in centuries past. She says that “culturally sanctioned, socially acceptable behavior now, in women as in men, is the ability to play down qualities that have been traditionally considered feminine and play up the qualities that have traditionally been considered masculine”. The concept that this ideal, “strong female character” is predicated on masculinity and masculine presentations of strength is a fascinating one. Chocano states that these characters “reinforce the unspoken idea that in order for a female character to be worth identifying with, she should really try to rein in the gross girly stuff”. The somewhat paradoxical distortion that occurs is that this attempt to strengthen female characters, a reasonably feminist goal, is carried out by ascribing to such characters traditionally masculine traits. There is a misogyny in the way that a project of equalizing the value and quality of female and male characters has deviated from that goal and become a project of “elevating” female characters by masculinizing them. By interpreting the desire for strength in female characters with this specific definition of strength that is centered on the conventionally masculine, the patriarchal hierarchy where masculinity is valued above femininity can be preserved.

There are a couple of ways in which this gets configured, and they often overlap and intertwine. These masculine definitions of strength are imposed on female characters to evoke a false and appropriative “empowerment” branch into two main areas, the first being a complicated kind of hypersexuality divorced from “girly” feelings and emotional attachments-- a kind of relationship to sex that is conventionally attached to masculinity that includes a constant willingness and interest in sex that is separate from emotion. When applied to a female character, such an attitude toward sex is painted as “empowerment”. A recent case in pop culture which sparked a conversation about the usage of “empowerment” language intersecting with hypersexualized female characters was DC Comic’s reboot of their character, Starfire. They came under fire by many fans for the alteration of Starfire into a significantly more promiscuous character, to which many others calling the backlash slut-shaming and arguing that the new Starfire’s sexuality is an example of empowerment. Blogger Laura Hudson of Comics Alliance examined the issue and argued in her article “The Big Sexy Problem with Superheroines and Their 'Liberated Sexuality'” that “the sexual dynamics that are in play here both creatively and culturally” mean that instances like this “don't support sexually liberated women; they undermine them”. A key point that Hudson goes on to make that often gets overlooked in the discourse surrounding these issues is that there is a core problem with the idea of a “sexually liberated” female character-- they aren’t real women. The problem with Starfire is not that the idea of a woman being promiscuous or overtly sexual is wrong or bad or shameful, the problem is that Starfire isn’t an actual woman with agency who gets to make those choices about her sex life. A character is a very different entity than a real woman, and when a character like the rebooted Starfire is written and drawn to be a certain way it is in fact “not about these women wanting things; it’s about men wanting to see them do things, and that takes something that really should be empowering--the idea that women can own their sexuality-- and transforms it into yet another male fantasy”. One obvious way in which the real intent of the prevalence of the “strong female character” whose supposed “strength” lies in her hypersexuality becomes obvious is in the fact that these characters are inevitably conventionally attractive women that preserve the standard male fantasy of what a woman is or should be like. Appropriating the term “sexual liberation” and other language surrounding female empowerment for the purpose of these fictional women who are often written by men and certainly created with an audience of men in mind turns actual female agency into an eroticized, fictionalized contrivance. It allows that language of empowerment to become oppressive and accusatory-- empowerment and sexual liberation does not necessarily equal the specific kind of sexuality present in the narrative of Starfire. Moreover, the problem is compounded by the lack of diversity among the media depiction of the strong, “empowered” woman as being “sexually liberated” in this very particular and singular way that in actuality has very little to do with the development of a rich and complex female character and very much to do with a simplistic pleasure mechanism for the audience.

The second very common way in which “strong female characters” are created by imposing a masculine-identified kind of “strength” upon a female character and then undermining even that form of power is in the case of the high-powered woman archetype who is either very physically strong or highly positioned in a career field. While there are a great many ways in which this archetype is very powerful and even subversive-- a woman in a predominantly male field is admirable and a good role model, a woman who is has a lot of literal bodily strength is an overturning of the weakness usually associated with femininity-- there are also many ways in which it can also be problematized. For one thing, oftentimes a female character whose “strength” comes from her high-powered career is the only female among her colleagues, serving as the token woman and therefore acting as professional, calm, and collected at all times. It is problematic in that it arises from a system which makes it an accepted and predominant narrative in which there is a token female character who must not have many (or even any) flaws in order to be able to be representative of women. But even as this “strong female character” is in fact one who is admirable and serves as a good role model, this put-together demeanor often serves as her only atttribute.

Tavi Gevinson, a 15 year old girl who has run a very successful fashion blog for the past four years and is now the editor-in-chief of RookieMag.com, an online magazine aimed at teenage girls, is a self-described feminist who gave a TED Talk exactly about “strong female characters”. In it, she argues that the characters often troped as “strong female characters” are like “cardboard characters,” disappointingly and damagingly two-dimensional and unrealistically underdeveloped. Women, she points out, are complicated because people are complicated, and she calls out simplistic depictions of women as problematic because “people expect women to be that easy to understand and women get mad at themselves for not being that simple" (Gevinson). This has many consequences to average women, whose role models in media must be this shining beacon if she is to exist at all. Even real women celebrities seem to largely be held to these standards, and it is a pop culture favorite to morbidly savor the fall-from-grace that occurs every time a female celebrity at all breaks out of the mold. Britney Spears, her younger sister Jaime Lynn Spears, Miley Cyrus, Lindsay Lohan, Paris Hilton-- a handful of examples among many where flaws in the facade that they were expected to uphold as women in the public eye damned them to a veritable storm of negative media attention. Gevinson is truly hitting a core point that opens up the real possibilities missed by the “strong female character” trope-- that perhaps even when successful, a “strong female character” who is flawless and glittering onscreen does not serve women who are real and human and flawed. The standard perpetuated even by the good role models is harmful to the actual women who are then held to such an impossible standard.

Carina Chocano’s article, "Tough, Cold, Terse, Taciturn and Prone to Not Saying Goodbye When They Hang Up the Phone," argues that “traditional ‘strong male characters’ have been almost entirely abandoned in favor of male characters who are blubbery, dithering, neurotic, anxious, melancholic or otherwise ‘weak,’ because this weakness is precisely what makes characters interesting, relatable and funny.” This is a daring claim, but one that seems to be cropping up more and more in the discourse surrounding the issue of the “strong female characters”. Perhaps, a truly strong female character lies in well-written, whole characters who happen to be female-- and the way to write such a multi-faceted character is to include weakness, struggle, and failure.

To hold up failure as a queered form of successful achievement of freedom is an idea explored by theorist Judith Halberstam in “The Queer Art of Failure”, in which Halberstam proposes that “feminists refuse the choices as offered” and think about a resistance that “articulates itself in terms of evacuation, refusal, passivity, unbecoming, unbeing” (Halberstam 129). Particularly interesting is the use of the word “unbecoming” with its dual meaning, both a refusal to become and “unflattering”. In this, Halberstam’s theorization joins very nicely, cleaving an “unbecoming” image of women in media to resistance articulated in a refusal to become. If strength is conventionally an inherently male trait, a female character that serves women cannot also be strong-- that would be an acceptance of the choices as offered, it would not subvert but rather play neatly into a patriarchal system which easily allows for women to strive for and fail at acquiring male attributes. Rather, female characters that serve women can embody a sort of queered weakness by refusing to become strong, with all of its patriarchal underpinnings, allow themselves the unflattering position of being portrayed as flawed and complicated and human. Perhaps, according to Halberstam's theorizations, there is more to our damsel in distress than meets the eye.

Beaton, Kate. "Hark, a Vagrant: 311." Hark, a Vagrant. Web. 9 May 2012. <http://harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=311>.

Beaton, Kate. "Hark, a Vagrant: 336." Hark, a Vagrant. Web. 9 May 2012. <http://harkavagrant.com/index.php?id=336>.

Chocano, Carina. "Tough, Cold, Terse, Taciturn and Prone to Not Saying Goodbye When They Hang Up the Phone." New York Times 1 July 2011.

Hudson, Laura. "The Big Sexy Problem with Superheroines and Their 'Liberated Sexuality'" Comics Alliance. Web. 9 May 2012. <http://www.comicsalliance.com/2011/09/22/starfire-catwoman-sex-superheroine/>.

Gevinson, Tavi. "Still Figuring It Out." TEDxTeen. 9 Apr. 2012. Lecture.

Halberstam, Judith. "Shadow Feminisms." The Queer Art of Failure. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2011. Print.

other resources

http://io9.com/5844355/a-7+year+old-girl-responds-to-dc-comics-sexed+up-reboot-of-starfire

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cYaczoJMRhs

***image by Kate Beaton