Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

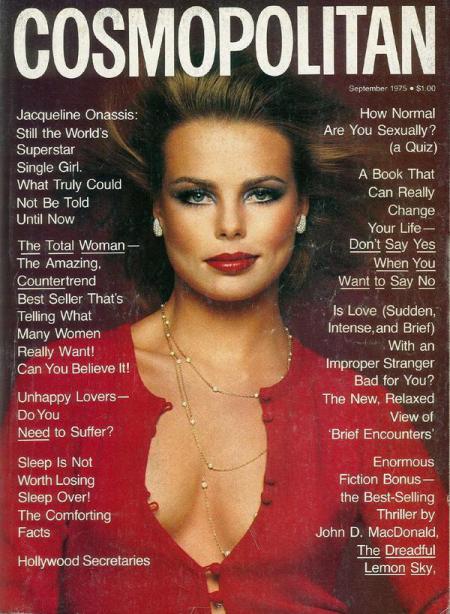

Cosmopolitan Power Feminism and Bad-but-Good Cosmo Girl

I want to explore a text that is considered by mainstream audiences to be a text of female empowerment: Cosmopolitan magazine. I particularly am interested in the way that Cosmopolitan simultaneously instructs/ “empowers” women to reverse the male-female power dynamic through sex and tells them to feel guilty for doing so. The ideal Cosmo girl both objectifies men and feels ashamed of doing so; hence the woman who reverses this dynamic without this requisite guilt is considered shameless and worthy of judgment.

McMahon mentions early on that the magazine rose to prominence as a source of female empowerment (this is not to say it was universally understood as empowering; it was, and is, a controversial text) only after it came under the leadership/editorship of Helen Gurley Brown who at the time (she was editor from 1965-1997) and changed it’s purpose from a periodical of fiction stories to an extended advice column for the single, sexually liberated woman. McMahon does describe Brown as someone considered by Ms and The New York Times (during the 70s and 80s) to be somewhat of a feminist providing “ ‘half a feminist message’ to women who would otherwise have none (New York Times Magazine, 1974)” (McMahon 382): Ms referred to her as “the women’s magazine editor that first admitted that women are sexual too” (July 1985—30th Anniversary Issue). Thus she was considered and for the most-part is considered “somewhat” of a feminist innovator.

I have considered Cosmo’s message too normative to be at all empowering, and as far as I can see its message and method have not changed in the past forty years. If feminism is about liberating all people, or even only women, from the oppression of “shoulds” regarding gender and sexuality, then Cosmopolitan is not feminist because it is only dismantling old “shoulds” while creating new “shoulds”. Yet Cosmopolitan has been enormously successful specifically among 20-ish traditionally college age woman, so it must be providing women with a message they want to hear, or find necessary. This success might indicate first, that when it comes to sex there is no limit to how much people want to hear (Foucault definitely understood this) and second, that there is a strong interest in knowing what sex is “normal”, or what sex should be. But I think McMahon’s account creates a very accurate picture of the very narrow form of power feminism that is considered by the general public to be Feminism. bell hooks understood mainstream feminism as a straightforward power feminism—McMahon understands this as well, and through the lens of Cosmopolitan demonstrates the limitations of power feminism—particularly the its libratory potential.

McMahon describes the power feminism implicit in Cosmo as rooted in the way it addresses relations between subjects (male-female relations) as products of a public market exchange—sex and relationships are explained in terms of winning: men have always been winners, now women need to come and replace men as the winners. The key novelty of this understanding is the implication that women can and should enter into this public sphere where their sexuality is welcome. This is a very classed, white, first wave feminist stance, in which the aim is to liberate women from the home and the “domestic and procreative” understandings of sex that accompany this limited space.

Beyond the marketplace metaphor of sex, McMahon finds the “fantasy” depicted in Cosmo problematic. She describes the way that the magazine portrays itself as providing solution for the everyday problems of the Cosmo girl, it actually serves to “maintain and even emphasizes conflicts while offering fantasy as temporary amelioration of anxiety or as containment of conflict” (McMahon 384). I think this manufacturing of female anxiety is still a large part of the Cosmopolitan ideology: it serves to make the magazine eternally necessary—if an issue actually “solved” on of these numerous conflicts then it would cease to be useful and necessary. The Cosmo girl is a one who constantly needs to know what to do—what she should be doing. Cosmopolitan both manufactures and satiates this need. This notion of the world as a bad, dangerous one full of endless strife makes it more acceptable for women to discriminate against the bad men, and even all the other women with whom she must compete. Cosmo creates a war zone of sexual relationships in which a woman can only depend on herself.

The Cosmopolitan power feminist female liberation can only be achieved through the reversal of male domination and hence the oppression of men: “the freedom of one individual is defined as the unfreedom of another” (McMahon 386). The Cosmopolitan woman must subordinate men as objects, or face objectification herself; yet, the woman successful in this reversal of power who effectively “depersonalizes (men) to the point that she doesn’t recognize them” is commanded to feel guilt about doing so—only her guilt can excuse her behavior and ensure her purity of heart. The Cosmo girl is necessarily a “good girl at heart” (McMahon 391). This expectation of female guilt is ubiquitous in modern depictions of sexual women; this is exemplified by the cliché of the “hooker with a heart of gold” or the “innocent whore” turned to prostitution by the dirtiness of the world (Pretty Woman et cetera). The problem with Cosmopolitan is not its power feminism—that is unavoidable everywhere, it is Feminism as far as mainstream audiences are concerned. The problem is the prescription of guilt—a guilt that has metasisized into the ability of women to discriminate against other women. It has created a hierarchy that subjugated the genuine slut beneath false slut. In effect, a woman’s goodness is defined by her intention and degree of pleasure. If she actually enjoys this perpetual objectification prescribed by power feminism then she is dirty and a whore, but if she feels bad and is remorseful, yet does it anyway she is redeemed. Today a woman is saved from her sluttiness by the fact that it’s not her ultimate desire—her ultimate desire is to be a subject in relation to another subject, yet she objectifies men out of necessity, out the need to survive in a man’s world. If she dares to actually enjoy and desire to use others for sex then her actions are tainted.

In sleeping around for the pursuit of love the Cosmo girl gains the power to discriminate against other women. This is what is abhorrent to me in Cosmopolitan and all that has flowed from its ideology. While the prescription of power feminism and its redefinition of rules (rather than the elimination of rules) is misguided, it is not nearly as damaging as the prescription of female guilt which produces nothing but a new means for women to subjugate their fellow women. While it is frustrating to see a new version of female expectation created under the banner of female empowerment and emancipation, I don’t see power feminism as pushing the “women’s movement” backwards. But once the text moves from power feminism to endowing particular women with the power to discriminate against and oppress other women—to marginalize them anew—then this text has shifted into the realm of actively working against the movement to end oppression. The power feminism of Cosmopolitan might be ultimately ineffective/unproductive, but it is the prescription of guild and permission to judge that makes Cosmopolitan explicitly counter-productive. This counterproductive hierarchy has seeped out of the popularity of the magazine and out into other texts of female empowerment. A show like Sex and the City, which draws explicitly from the sexual liberation that Cosmo proclaimed, places female characters in hierarchies based upon the intention and degree of enjoyment in their sexual behaviors—ranking them from well-meaning promiscuity down to unrepentant “slut”.

McMahon, Kathryn. “The Cosmopolitan Ideology and the Management of Desire”. The Journal of Sex Research. Vol 27.No 3. Aug. 1990, pps. 381-396.

hooks, bell. Feminism is for Everybody. South End Press: Cambridge, 2000.

The pictured issue from September 1975 is one my mother bought right before she started college. I found it about six years ago in her parents' basement. I've been thinking about this topic since that time.

Comments

i was actually going to add a paragraph about that...

But I was afraid what I was saying would seem to imply that only women desire an environment of strife in which there is always a new problem to be solved. If a the message of Cosmo has been over and over again, generation after generation, received with open arms, then it must be saying something or addressing something women want to hear. Perhaps the fantasy of Cosmo are the very problems it addresses--maybe it frees readers from real problems in their lives by addressing issues like "should I have sex in the shower or in bed?". Maybe the draw of Cosmo is the solidarity behind the problems--it feels good to be united with all these other readers, experiencing the same oppression that you are experiences--rather than to be alone in a personal or very pertinent problem like "I don't have rent money" or "I got dumped" or even "I am lonely". I guess this escapism I am describing is the very purpose of entertainment in the first place. Cosmo and Sex and the City are both equally forms of entertainment, means of distraction.

But beyond that, to return to my first idea, I do think that there is a desire for conflict that the text of Cosmo has been responding to for the past 40 years. The Cosmo quiz is legendary and ubiquitous because it responds to a need, to a demand. As McMahon describes the text does in many ways push its readers to compare themselves to the idealized Cosmo girl, but there is an implicit desire in taking the quiz in the first place, that this quiz taker wants to compare themself to some standard. It's exciting to be caught in the middle of the tangled jungle of sexual relations in which at every turn there is a big bad man who might use you and toss you right back into the war zone. There are limitless dilemmas to be solved in this jungle. One things for sure, you'll never be bored.

BUT again, perhaps McMahon and I are simply taking Cosmo waaay too seriously. I read that 1975 Cosmo, and I have definitely flipped through more than a few times since High School. And I can say definitively that I doubt anyone takes the Cosmo quiz or even most of Cosmo's advice too seriously. There are only so many ways to say "do something new! bite his ear!" in 12 issues a year...and the quiz is just a sexualized version of goldilocks in which you are either too sexual, juust right, or not sexual enough, in which case there's no hope for you--you're a spinster. (This is actually one of the categories from a quiz in the 1975 issue, I remember the category "spinster" distinctly. If you selected too many "c's then you were destined to spinsterhood.)

People with actual dilemmas write Dear Abby, not Cosmo...

now I truly do not know what I am fighting for

Limited liberatory potential?

dear.abby--

Towards the end of the semester, when I'd pretty much "had it" with your all's insistent, repetitive "setting the scene" with problematic pop cultural images of women's sexuality,--I was REALLY TIRED of being shown music videos that objectified women--I said something like, "how about you all bring in something empowering? If you can't find it, create it!"

So, fair warning: that's the orientation I bring to this essay. It's sharp, thoughtful, and provocative in its analysis of Cosmo as representing a "narrow form of power feminism," with very "limited liberatory potential." You do a nice job of demonstrating those limits, by cataloguing the ways in which the magazine presents "relationships as products of a public market exchange, explained in terms of winning"; manufactures female anxiety, then produces fantasies to ameliorate it; creates a world in which “the freedom of one individual is defined as the unfreedom of another,” in which "female liberation can only be achieved through the oppression of men." The nicest turn of our screw (sic) here is your condemnation of Cosmo's "prescription of guilt," as not just damaging the guilty woman, but subjugating other women, too.

But. Having. Said .All. That. I'd be very interested in nudging you beyond a catalogue of the limitations of popular magazines (or t.v. shows, which you seem to promise in your essay's final paragraph). What is it, anyway, about human psychology that demands, over generations, the sorts of stories that Cosmo and Sex in the City provide? Why do we buy, repeatedly, over time, in such great numbers, stories that fail to "liberate all people from the oppressive 'should,'" by simply creating a new "should"? Why do we seek the repetition of oppressive structures, the normative, rather than truly liberating representations of what we might be, and how we might act with one another, as human beings? Those are the questions I'd like to hear answered!