Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Female Genital Mutilation

Rebecca Sheriff

Female Genital Mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting is a

practice that has been going on for thousands of years based in northern Africa, the

Middle East, and parts of south Asia. Although there are claims that FMG is done for

religious reasons, there are no passages in the Koran, Bible, or Torah supporting FGM.

Because FGM has no health benefits, but instead serious health risks, including death, the

World Health Organization (WHO), Human Rights Watch, and countless other

organizations are trying to put an end to it. Many countries including western nations that

have immigrants from the main countries of FGM , have made FGM illegal. Several

politicians and activists have proposed implementing mandatory gynecological exams in

elementary schools for at risk students, but this has been rejected. The governments of

these countries who have outlawed FGM are working with many organizations like

UNICEF, Amnesty International, and WHO to take preventative measures, which mainly

consist of spreading education on the affects of FGM.

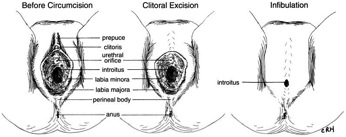

Female genital mutilation is classified into four groups. Type 1 is the excision of

the clitoral hood, usually as well as the clitoris. Type 2 is the excision of the clitoris and

inner labia. Type 3 is commonly called infibulation, which consists of cutting off all

external genitalia, and then binding the girl’s legs together for 2-6 weeks so a scar will

form over the opening of the vulva. Before this huge scar is formed, a twig is usually

stuck in between the flesh to create a small hole for urine and menstrual blood to flow

from. The hole that is produced is initially made small enough to prevent women from

having sex, but this is problematic because the small opening obstructs blood and urine

flow, which causes infection. When a girl who has infibulation is about to have sex the

man either tries to force his penis through the hole, or has to cut it with a knife which

frequently results in organ damage, urinary incontinence, obstetric fistula, and death (7).

Type 4 includes the following damage to female genitalia: pricking, piercing, burning,

cutting, applying corrosive substances to tighten it, and cutting into the vagina to widen it

(7). FGM has many harmful effects such as: hemorrhaging, urinary infection, hepatitis

and HIV (due to unsterile tools), pelvic infections, epidermoid cysts, and infertility (5).

The pictures and charts below can help conceptualize this information.

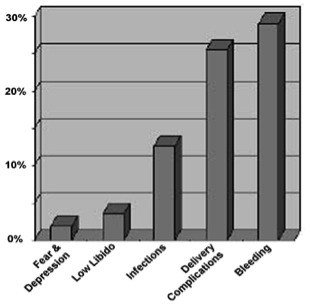

Chronic FGM-Related Complications Encountered by Health

Providers in Kenya

FGM is practiced in 28 African countries, with incidence varying from 98% of

women in Somalia to 5% is Zaire. FGM is also found in Oman, the United Arab

Emirates, and Yemen, as well as in parts of India, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Immigrants

from these countries to Europe, Canada, and the United States continue to undergo FGM.

Overall 85% of women who have FGM have Types 1 and 2, and 15% of females have

Type 3; but some countries like Somalia, Sudan, and Djibouti have almost exclusively

Type 3. Approximately 100-140 million females have undergone FGM, with an

additional 3 million girls and women undergoing FGM every year. The following picture

is shows the prevalence of FGM in Africa.

Many people claim that FGM is necessary to be a ‘good Muslim,’ but there are no

passages in the Koran that support this; in fact the Koran states that it is forbidden to

mutilate God’s creation. In Sura 95, Verse 4, the Koran states: “We have created man in

our most perfect image”. Islam, Christianity, and Judaism “define man as a perfect

creation of the Almighty, and condemn doing any harm to God’s creation” (8). Women

from countries with high rates of FGM are afraid of not being cut because they will be

perceived as being unclean, and can have trouble finding a husband. Myths are spread

around in FGM areas that the clitoris grows so big it will rub your clothes and be

uncomfortable. The following graph shows the beliefs of FGM in certain African

countries.

Reasons for Supporting FGM in Egypt, Mali, Central African Republic,

and Eritrea

FGM violates many human rights charters, and organizations’ beliefs. The

following is an example of the countless violations people feel FGM creates. The

African (Banjul) Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights take objection with the

following aspects of FGM: the right to life could be violated, the right to health could be

violated, the right to physical integrity could be violated, which includes freedom from

violence, the right not to be subjected to torture or ill treatment could be violated, the

right to non-discrimination could be violated, and specific children’s rights could be

violated (8).

Because many people consider FGM a violation of human rights of girls and

women, countries have been outlawing this practice since the 1980s. Because the U.S.

and European countries have received immigrants who practice FGM, these countries

have started penalizing FGM. Sweden was the first western country to pass legislation

banning FGM in 1982. Since 1982 the following industrialized nations have passed laws

criminalizing FGM: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Italy, New Zealand,

Norway, Spain, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States. France uses existing

criminal legislation to prosecute both people who perform FGM and parents who get the

service for their daughters. The following African nations have made criminal legislation

banning FGM: Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d'Ivoire,

Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal,

South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, and Nigeria (1). The penalties range from 3 months to life

in prison, as well as monetary fines.

In some countries like England and France, you can be prosecuted even if you

send your daughter abroad to get FGM. “In the UK, the Prohibition of Female

Circumcision Act 1985 outlawed the procedure in Britain itself, and the Female Genital

Mutilation Act 2003 and Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005

made it an offence for FGM to be performed anywhere in the world on British citizens or

permanent residents.” (5). Although so many countries have outlawed FGM, it is very

hard to monitor because it involves genitalia. Former member of the Dutch Parliament,

Ayaan Hirsi Ali, activist Kadra Yosuf, politician Nyamko Sabuni, and others have

proposed a mandatory physical examination among girls from the risk group. Ayann

Hirsi Ali proposed that these examinations happen in grade school, with the hope to

discourage female circumcision. The Dutch parliament said that was not possible because

“(1) it would be considered discriminatory to only let girls and women from specific

countries undergo a physical examination; (2) the Dutch law does not provide for the

possibility of a mandatory physical examination in FGM cases; (3) a compulsory physical

medical examination would interfere too much with the private life of a person and would

therefore violate article 10 of the Dutch Constitution, article 17 ICCPR, and article 8

ECHR” (8).

The main way governments, NGO’s, and social justice groups are trying to

combat FGM is through prevention by empowering women with education. The

following are examples of prevention. The Inter-African Committee on Traditional

Practices, with the help of NGO’s has started an extensive educational campaign in over

20 African countries, with the goal of eliminating FGM. The United States is trying to

eliminate FGM through policies that include education, the empowerment of women, and

enforcement of laws against FGM. The Dutch prevention policy consists of awareness

raising, education and training of medical professionals and health-care workers, and the

empowerment of women.

Although people are attempting to eliminate FGM, organizations such as

Amnesty International want to respect culture by replacing physical FGM with symbolic

ceremonies. The main goal of eliminating FGM is for female’s integrity and safety, not to

ignore traditions that include a rite of passage (9).

Bibliography

1) http://reproductiverights.org/en/document/female-genital-mutilationfgm-

legal-prohibitions-worldwide

2) http://reproductiverights.org/sites/crr.civicactions.net/files/documents/B

RB_FGM_10.08.pdf

3) http://www.ednahospital.org/hospital-mission/female-genitalmutilation/

4) http://www.socialcohesion.co.uk/files/1231525439_1.pdf

5) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:FGC_Types.svg

6) http://www.path.org/files/FGM-The-Facts.htm

7) http://www.ednahospital.org/hospital-mission/female-genitalmutilation/

8) http://www.stopfgm.net/dox/SPoldermansFGMinEurope.pdf

9) http://www.global-sisterhood-network.org/content/view/1470/59/

10) http://feminist.org/global/fgm.html

Comments

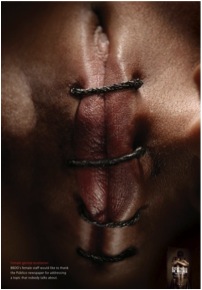

photo of sewn vagina

Dear Rebecca,

I am a Sex Educator putting together a large, inclusive web site and would like to include the powerful photograph in your article for the section on FGM. Would that be okay?

And thank you so much for putting this strong, well-researched article on the web!

-Shain Stodt

Genital surgeries?

buffalo--

you've done a power of research about a very controversial issue, one that highlights the questions of cultural difference that you gesture towards just @ the close of your study. I'd appreciate fuller citation for each of your sources--your list of url's doesn't tell me who wrote this material, under what circumstances, or on what dates.

If you'd like to go on thinking about these issues for your next project, I'd recommend your beginning (again) in two directions: first, by finding out more about how women on whom these procedures are performed (and who perform these procedures on their own daughters and nieces) describe and justify their practices; secondly, by learning more about genital surgeries conducted in this country, both on little boys (= male circumcision) and on infants w/ ambiguous genitalia. For the first topic, some sources include

Warrior Marks. Dir. Pratibha Parmar. Videocassette. Hauer Rawlence, 1993. 54 minutes.

Fire Eyes. Dir. Soraya Mire. Videorecording. Persistent Productions,1994. 60 minutes.

Dorkenoo, Efua and Scilla Elworthy. “Female Genital Mutilation: Proposals for Change.” London: Minority Rights Group, 1992.

Lane, Sandra and Robert A. Rubinstein. “Judging the Other: Responding to Traditional Female Genital Surgeries.” Hastings Center Report 26, 3 (1996): 31-40.

for the second, see, for starters,

Slaughenhaupt, Bruce. “Diagnostic Evaluation and Management of the Child With Ambiguous Genitalia.” The Journal of the Kentucky Medical Association 95 (April 1997): 135-141.

Erik Parens. “Thinking about Surgically Shaping Children.” Surgically Shaping Children: Technology, Ethics, and the Pursuit of Normality. Johns Hopkins, 2006. xiii-xxx.

As with your last web-event, by suggesting these readings, I'm nudging you towards a project that frames the issues less starkly as "pro" and "con," as "us" vs. "them," placing the questions you raise and the answers you offer on more of a nuanced continuum. You might want to look, too, @ the work of some of your classmates that looks @ feminism "across geographies"....