Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Play in the City 2013

still open for conversation!

This on-line forum will remain open...our ESem still here for us collectively.

We hope you all will post here in the years to come.

On the last day of class, Mark and Anne said,

"We think that what we have accomplished together (all of us) is important. It's important because play is the lifeblood of being an authentic intellectual and it's also profoundly healthy. We've assembled a toolbox together--a full, rich array of strategies to use when you are stuck or feeling unconnected to reading, writing, or talking in class.

We think it's important that you each have connections to the city--multiple connections. And that there are 25 other people in your class who understand their connection to the city and on whom you can rely to nurture your connection to the city. Bryn Mawr is an amazing place and one of the amazing things about it is that you can really nourish yourself, socially, emotionally, culturally and spiritually through your connections to the city and to each other.

We hope you feel connected to one another, to at least some of the ideas that we've worked on together, to the notions of play we have explored, and to the city in which we've all played--critically, deeply, and in friendship.

The two of us are happy to be resources to you during your time here--and after. If you're curious about something (something related to Bryn Mawr, to intellectual life, or to the city or your well-being), please be in touch with us.

Self Evaluation

Three months ago, with excitement and a little bit worry, I, an international student from China, came to the United States for the first time. Everything around was new for me, especially, the language environment. At the beginning, when I had to speak English all the time during my daily life, I felt awkward and tired. Even worse, I faced difficulties of various sorts in writing— sometimes, I faced culture collisions; sometimes, I misunderstand the meaning of words; sometimes, I clearly knew what I want to express, but when I started to type, I was trapped and even had no idea about how to build up my words into a shapely essay. Luckily, I joined Esem "Play in the City"this semester. Although it was not easy for me to read so many reading materials and write my essays every week, I, indeed, have to thank for those experiences because I learnt many precious skills of writing from them.

During this semester, we had at least seven trips to Philadelphia, which were all interesting and exciting. We explore the meaning of new definition we learnt in the readings in class; we visited museums; we watched plays; we took photos; and we absorbed knowledge and thinking a lot when we played and enjoyed ourselves.

Unconsciously, three months have passed. These days, I practiced reading and writing to developed my skills of using my second language, which is like that I piled up my experiences as bricks to build up a skyscraper—more bricks I built, higher I reach, and further I overlook. Thus, I will never stop my steps to collect the “bricks”, which build up my second language and bring me to a wider horizon of my new life.

Rewrite Deep Play

Rewrite Deep Play

I am in a daze, sitting in front of my laptop, my eyes staring at the photo of my little cousin Sam on the screen, thinking about that I would never notice that I did a kind of “ deep play” with him before without taking this course and reading the article by Ackerman.

Play is an activity enjoyed for its own sake, while deep play is the ecstatic form of play, which is a fascinating hallmark of being human. (Ackerman) With my own experience, I state the definition of deep play as a kind of play that not only bring fun, but also express something deep inside the players. During most of my playtime, I just have fun—search the Internet, play games or do some sports without think deeply and express anything from my heart. However, when I played hide-and-seek, the common game which seems may not be consider as a deep play, I thought much more than the game itself and did a deep play.

“Five, four, three, two, one …… I am coming!”

I still remember that it was my first time to play hide-and –seek with Sam, a five-years-old boy. I was a seeker and he was a hider. Actually, it was extremely easy for me to find him—he was hidden under the quilt and his back was like a little hill on the bed. Thus, I walked to the bed directly and opened the quilt quickly without any hesitation. I felt proud to be “clever” to find him while he looked a little bit embarrassed and upset. Looking at his bright eyes with depressiveness, I suddenly realized that I had made a mistake—I should not play this game so seriously.

I though of those days my parents played hide-and-seek with me when I was 5 years old, and that was a kind of “deep play”I even left my slippers on the floor in front of the clothespress in which I hided. However, my parents never exposed me directly like I did to my cousin. Instead, they acted like that my technique of hiding was wise enough to avoid their carefully searching. More often than not, they talked to each other loudly to make sure that I could hear clearly: “Where is she? I have no idea at all!”,“She is quite a talent hider!”. Every time I heard such words, I could not control myself and laughed out loud. Even though, my parents would never “find” me until I jumped out by myself.

Stopped recalling my memory of childhood, I began to understand that the game I played was not as simple as it looked like. Different way to play could lead to different result and if I did not care about to be a winner, the result would be better, such as I could make my cousin happy and set up his confidence. Therefore, I decided to change my way to play this game. I went to him and persuaded him to play one more time by giving him a lollipop, and he agreed reluctantly. This time, he hided behind the curtain and, as usual, I saw his feet at once. Nevertheless, I did not point it out immediately, but behaved like my parents did before.

“Where is him? I cannot find him! That is impossible!” I shout aloud.

Faintly, I heard his laughter but ignored.

“How smart he is! I think I have to give up…” I kept acting and felt much more proud than the last time, and that was my first time to felt happier to be a loser than when I was I winner.

“Aha! I am here!” Finally, Sam jumped out of the curtain. He looked so excided and cheerful, just like I had been when my parents played with me before.

This experience of “deep play” impacts me a lot. As the definition I stated in the first paragraph that deep play should be able to express something deeply inside the players, I not only had fun but also expressed my love to my cousin inside my heart when I played with him.

Work Sites

Ackerman, Diane, Chapter One. Deep Play. New York: Random House, 1999.

NW Revisited

Although at first glance the chapter naming system in NW, by Zadie Smith, seems almost arbitrary, there is an underlying intent behind the chapter-nomenclature. This paper intends to examine how the Natalie and Leah’s reactions towards their pasts are revealed through the chapter titles within their sections of the book: Visitation and Host.

The first section, Visitation, focuses on Leah, who desires very much to appear ordinary, and would like nothing so much as to stay still, living in a certain point in time. She does not necessarily desire objectivity; she does not necessarily even consider the past that much better than the present, although it is clear that in many ways she does. She wants to stay in a fixed point in time, because she more or less likes her life, and she does not want it to change. The New Oxford American Dictionary defines visitation as “an official or formal visit, in particular 1. (in church use) an official visit of inspection. 2. The appearance of a divine or supernatural being. 3. A gathering with the family of a deceased person before the funeral.” The title of this section is fitting, then: Leah is constantly examining and re-examining her past, visiting it, and sometimes visited by it, as if it could offer some form of divine protection or favor. In doing so, she has in many ways refused to go on living, preferring to try and stay stationary in time. Of the 27 chapters within the section, they are organized in the very typical, traditional Arabic number system, with only four exceptions; there are four separate occasions where the numbering system skips a chapter; instead of the chapters lining up 17 – 18 – 19, they instead read 17 – 37 – 18. These chapters 37 correspond with chapters wherein Leah attempts to forestall the future.

The first chapter 37 is between chapters 11 and 12, and is only a page long: therein Leah remembers a former true love telling her that humans are naturally drawn to the number 37, and that it will keep showing up throughout life. In the chapter, the scene shifts to contemporary Leah, frozen with indecision or fear, as she considers approaching the people squatting in Number 37 Ridley Avenue. Leah can not convince herself to confront these new intruders, to admit that squatters had moved in, that something had changed; much safer, much simpler, to go on as if it had never been, and to absorb her self with the past. If she approaches these intruders, then she will be forced to admit that they did not used to be there. If she approaches the intruders, she will force them to respond, and they might not respond well; that is another reason she hesitates, out of fear of that response and what it might do, what it might change. “What would she do with 37 lives!”. (46) If she had assurance that things would not change if she confronted the men, this comment implies that she might approach them. This sort of promise is not actually uncommon for Leah, either: throughout the book, she finds herself thinking about how she would act if only something or another were different. Were something to change, however, she would not actually act differently than she did before the change: this is part of Leah’s unwillingness to inspire change, her desire to live in the past.

The next chapter 37 occurs between chapters 15 and 16, wherein Leah, unable to find any ‘discrete home remedy’, finds herself at a suspect clinic as she fondly remembers the before and the after of her first abortion. Again, the chapter 37 is as she attempts to forestall the future; Leah reasons that if she does not have a child, then it will always be Leah-and-Michel, just the two of them. “She doesn’t want to ‘go forward.’ For Leah, that way is not forward. She wants just him and her forever.” (103) Even before Olive’s death, she does not come into the conversation when Leah imagines her future joyful static life with Michael. That is her idea of paradise: the two of them, enjoying each other, with no one else to intrude or disrupt their happiness.

The third 37 is a mere page, a rant spoken by the Black Madonna, chastising her for her attempts to escape and avoid the past. The irony of this rant is that Leah has been actively seeking out the past, a stable place in time, for the entirety of the book up to this point; the diatribe presents it as if the same is true of the Black Madonna, but the her ‘stable place in time’ is centuries ago. This Black Madonna embodies the timelessness quality that Leah desires for herself, the feeling of a world stood still. Again, chapter 37 is where Leah finds herself drawn into the past and anchored there.

The last chapter 37, also the last chapter in Visitation, is notable for several reasons. To begin with, all the other chapter headings of the chapter 37s in this book were formatted differently. While most chapter headings were formatted bold with a period following, the chapter 37s were formatted italicized and free-floating, with the exception of this last chapter 37. In this last chapter, the heading is formatted to match the other numbered chapters thus far; this effectively foreshadows that while all the previous chapter 37s discussed Leah’s obsession with events prior to the book, the last chapter 37 covers her preoccupation with the events that occurred within the book; specifically, with Shar. This is reflected by chapter title’s formatting; while the chapter number is 37, indicating Leah’s chokehold on past events, the formatting is in the same format as the rest of the story’s chapters, as thus the other contemporary events, are.

By contrast, consider Keisha and Natalie’s section, Host. Host is the third section in the book: its “chapters” are of varying length, numbered and labeled in chronological order with a brief title to describe the contents or importance of the story covered in the chapters. The New Oxford American Dictionary defines host as “1. A person who receives or entertains other people as guests. 2. An animal or plant on which a parasite or commensal organism lives”. This is fitting for Natalie’s section. On the one hand, she ‘hosts’ the past through the various stories in her chapters, the stories flashing by like faces of people in a party, Natalie giving them just enough attention to greet them as they come in the door. On the other hand, Natalie is preyed on by her past, and has a mutually productive relationship with Keisha, Natalie’s other personality: she is, in effect, both types of host. Natalie’s chapters are in the expected order, with one exception: there is no chapter 37. Considering that most of the chapters in Host are connected to each other at least tangentially, and that chapter 36 was about Keisha not wanting to date a certain boy, and 38 was titled “On the other hand”, with merely the line “Beggars can’t be choosers”, this would suggest that perhaps the missing chapter 37 told the story of how Keisha and Rodney started dating. More to the point, Natalie, who tries so hard to ignore the past and forget where her roots come from, has thus lost chapter 37 as well. The closest thing to a chapter 37 is chapter 24, “The number 37”. This is fitting, for within this chapter Natalie remembers when Leah first took a train to Camden Lock Lot and the friends from Caldwell, who seem to be part of the reason Leah and Natalie grew to have such different personalities, and grew apart. Clearly, Natalie’s chapters, sometimes titled with a sentence, sometimes with a single word or a line of URL, focus on tales and memories. They follow one train of thought into another, never staying on one story for long. This mutability is similarly reflective of her desire to forget the past; she shows these traits within her stories, but also in how easily and quickly she throws away a story idea before moving onto the next one. 37 is important in Visitation due to its presence, but its importance in Host is due to its absence.

Only one idea repeats within the chapter titles: chapters 73 and 96 were both titled “The sole author”, and both reflect on some aspect Natalie as a person who made herself who she is through conscious decisions. This further emphasizes the desire to forget her past, because she deliberately seeks to separate herself from it, mold her self apart from it. Contrast this to Leah, who heard the line “I am the sole author of the dictionary that defines me” (3) almost before readers met her. Leah was drawn to that line, even tried to write it out to keep: all her pencil could write out was “I am the sole author”, refusing to adequately mark the magazine page with more. Leah was drawn to this aspect of the past, just as Natalie was repelled by it.

Although the chapter titles within Smith’s NW appear random at first, it quickly becomes clear that there is a code at work. In Visitation, all the chapter titles are numbers, and a chapter is only titled “37” when Leah clings to the past; in Host, there is no chapter number 37 at all, and the title “The sole author” is when Natalie steers her ship away from the past. In Visitation, Leah hears the quote “I am the sole author of the dictionary that defines me”, while in Host, “The number 37” is the train that introduced Leah to the people who would help her drift away from Natalie. On close examination, it seems obvious that the chapter titles in Zadie Smith’s NW help declare the attitude the character in question has towards their past.

Works Cited:

Smith, Zadie. NW. New York: Penguin Group, 2012. Print.

The New Oxford American Dictionary

Self-Reflection

When I first walked into Play in the City, I was a decent high school-level essay writer. Over the course of the semester, I learned more. I picked up more tools, things like ‘lenses’ and ‘the believing game’ for my writing toolbox, and these are tools that I expect to be very useful over the years. I discovered new terms and theories with which to interact with the world around me, different types of play and luck, that may or may not affect my writing in the future, but gives me different ways to think about my experiences: I consider that even more valuable to come away from a class with. In the end, I believe that I have improved in a few ways in my writing over the semester: I think about my essays differently, and in doing so I write them differently: I think about things like lens and how best to frame the point I want to make, what best proves my point or what point best discusses what I want to examine. I recognize, however, that I still have a lot to learn: my essays are not always as focused as they would ideally be, and they often have an overabundance of one punctuation mark or another. I thank this course further for that, because it not only taught me, but gave me an idea where to go next.

I enjoyed participating in class: the readings, while sometimes difficult, were usually interesting, even fascinating: sometimes this because of the idea of what if I took their advice and followed it through in the world, like what happened with Flannigan's "Critical Play". Sometimes it was because the essay sparked a moment of 'wait a moment, you mean I'm not the only one who does that?', as with Sontag's "Against Interpretation". The conversations were interesting, too: I usually learned something new, whether about a person, a topic, an idea. It was always exciting to see what someone would say next, whether or not I agreed with them, whether or not they or I were the only person in the room who disagreed with the class.

I think that overall, in the classroom I assumed the role of the prod, and often the devil's advocate: I often nudged people, poking at their ideas from one direct or another until they could fend me off, and leaving them with a stronger idea for it. When I was not asking questions about other people's ideas, I often asked them about my own. One of the reasons I love playing devil's advocate is that you can not play the role if you are unwilling or unable to poke holes in your own beliefs. I think of it almost as the cynic's version of the believing game: you may or may not believe for what you are arguing at the beginning, but if you play your cards right, everyone, including yourself, will be convinced by the end. Outside the classroom, I tended to serve as one of three things: I was the tag along, the conversation partner, or the crew director. On one or two occasions, I would up going on a trip with two classmates who were good friends with each other. This left me third wheeling, unable to join the conversations and not asked to do so. Sometimes I was with a bunch of friends or acquaintances that, although perfectly nice, could not be bothered to plan ahead. On these occasions I served as crew director, making sure everyone was where they needed to be when they needed to be there. Finally, my favorite situation was when I was traveling with people who I knew, liked, and who could get where they needed to without direction. In those situations, I was a conversation partner, and it was lovely. I think, however, that I learned from all of these roles: these are useful life skills, and the tips and tricks I learned this year will be useful next time I need to arrange a group of people, or to not step in and take over.

I do not know who I learned the most from: that was the lovely thing about this class, we all learned from each other simultaneously. Nor, for that matter, do i know who I was most helpful to: there were some students I barely interacted with, and some I developed good friendships with, but there was no single person I recognized spending a lot of time helping, or who spent very long helping me. That said, I found the class work, the class discussions, very helpful: I loved the point of view exercise after the trip to the Eastern State Penitentiary, because it was very interesting to see everyone's opinions so clearly written. I liked the concept behind the small groups of classmates responding to our writing as well, although I did not find those as helpful as I would like. I learned a lot during the class discussions, and I think that those helped me the most.

Overall, I am very glad that I took this course, and pleased that I can walk away from this new semester with all of this in my new toolbox.

Essay Rewrite #4

When I went to Zagar’s Magic Gardens, which is a concentrated space of his mosaics in one building, I was experiencing a form of escapism. The various details in the piece where too much too take in. The mosaic was made up of tiles, glass, found items, and homemade molds. A common theme was to have paint over the tiles, which outlined human forms and quotes about the city. The painted quotes often had misspelled words in them for example; “Forms are converes of meaning” In this quote “converes” might be converse, conveyers, or another word. Having this misspelling forces the quote to be open-ended and untranslatable.

I interpret the gardens as a space that welcomes you to be aware of your surroundings, but not necessarily to interpret or understand them. This is also true for natural gardens. Unlike other forms of art, people are often more willing to take form over interpretation when visiting a garden. This is facilitated by a garden being so large and detailed that it is nearly impossible to take in everything.

Looking at form is made easier in a garden because of its detachment from humans, which relieves the pressure for it to be useful or meaningful. Gardeners collect plants, arrange them in a space, and then let them grow and take root. Zagar is similar to a gardener in that he collects and organizes trash and then presents it in a space. The Magic Gardens are like a garden made of human trash, rooted in a city space.

Gardens provide a form you cannot take in completely, you are not encouraged to analyze it deeply, you are supposed to let it make you feel. Zagar’s Magic Gardens facilitate a space where people can look at the “the pure, untranslatable, sensuous immediacy of some…images,” in the way that Sontag describes in Against Interpretation. In this essay Sontag reflects on interpretation and it’s ability to hinder us from simply looking at art for the sake of looking, “Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there. This cannot be taken for granted, now....ours is a culture based on...a steady loss of sharpness in our sensory experience.” Sontag does not want us to look at art with a critical lens, but to rather look at it, see it, and let it affect us. I think in order to thoughtfully look at something and encounter it as a live creature; we must believe that there is something there to see.

Seeing is believing in something. Believing in art is a less biased and more naïve then a distinct point of view. However, it is still a side of compliance towards artwork. When I went to visit the Magic Gardens I believed in it because I looked and was entranced by the detail and encompassing beauty. I had positive emotions towards it because of I was witnessing. This pollutes Sontag’s idea to simply look at art without interpretation.

In cases when we doubt art Sontag thinks that this is the most important instance to believe in art, “Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. By reducing the work of art to its content and then interpreting that, one tames the work of art. Interpretation makes art manageable (and) comfortable” Sontag’s subliminal use of believing and doubting in her essay shows how she is built on the vocabulary we have learned this semester, as much as she is asking us to throw it out. In order to look at and let artwork affect you, you need to believe and doubt.

Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1966: 4-14.

How We Learn

How We Learn

In my elementary school, we had a day devoted to diagnostic testing. They had tests to determine what level of different classes we should be in. Tests that could show whether we were left-brained or right-brained. And they had tests that would determine what type of learner we are. I was determined to be a visual-kinesthetic learner with a strong preference toward logic and mathematics; I needed to be shown something and to do something with my hands and could solve problems more easily than many of my classmates.

This classification has lasted my entire life. I still learn best when I can see or touch what it is I am learning about and numbers and science still make much more sense to me than symbols and metaphors. This does not mean that I cannot learn through sounds or that I cannot understand the deeper meanings of certain things, it just means that I must work harder at it.

Different assignments in Play in the City allowed me to see these differences and recognize why some did not work for me.

When we were reading NW I struggled to believe what Zadie Smith said. I took all of her words at the dictionary definition because I never knew what was meant to have a deeper meaning and what was not. I wrote a paper on how Smith was wrong.

“Though seemingly realistic, Zadie Smith’s NW is loaded with inaccuracies.”

“In addition to the flawed character depictions, Smith also included many inaccuracies with geographical concepts.”

I could not accept her descriptions as anything but the settings of a story she wanted to tell. Her Willesden does not match the Willesden in the data and, in my head, she was wrong because of it. It was like trying to fit a square peg into a round hole, it would not work. I was frustrated because I could not connect to a place where I want to live, England.

When we started to discuss deep play I finally saw what the problem was. Every time I classified something as “deep play” I was interacting with some thing. It was never an idea or an activity, it was objects. The moment in the Titanic exhibit when “the young girl’s shoes before me were suddenly filled and a young man from third class was standing next to me. I could feel all of these people with me even though I was completely alone,” I was interacting with the artifacts from a disaster. Or when I was in the Barnes Foundation and “I [saw] the street in France where this hung. High above the street over the door to the locksmith’s shop, alerting people to its presence. It goes unnoticed,” I was connecting to a giant key. They were objects right in front of me. I could look at them from all angles and read the descriptions.

I wondered when I was looking at the locksmith sign “Why do I only have these feelings with artifacts?” but I now realize that it is because of the way I think and learn. Objects make sense to me because, like numbers, they are constant. The young girl’s shoes have looked as they do now for more than one hundred years and the sign for a locksmith has looked more or less the same since it was created in the 1800s. But Willesden, or depictions thereof, changes. I can not get a good idea of what the area is like because it is constantly changing and I need stasis.

Our first trip into the city, to experience “The Quiet Volume”, was another moment when I could tell that I was missing something. “The Quiet Volume” was interesting but it did not make me think about the world around me that differently. One of our last trips, to Eastern State Penitentiary, affected me much more. Both experiences involved listening to a person speaking directly into my ears, something that, as a visual-kinesthetic learner, is not particularly useful, and both involved observing my surroundings. So why was walking through Eastern State was a much more moving experience for me?

Touch.

Yes, during “The Quiet Volume” I had to touch the books and the table and turn pages, but at Eastern State, all of the touches were deeper. I touched a wall where a guard once leaned. I sat on the floor of a cell where a prisoner once paced. I was walking in history, touching it and feeling it, as opposed to sitting in a library with someone whispering in my ear.

The Titanic exhibit, the key and Eastern State, though very different, each provided me with something tangible. They were all things. Physical objects that take up space and can be seen from different vantage points. They are unchanging and touchable. I can interact with them.

It is not that I cannot understand that Smith’s novel presents one person’s view of Willesden or that “The Quiet Volume” makes people notice sounds around them. It is just that I do not think that way. I understand things through sight and feeling, numbers and logic not sound or symbols. I need the experiences and sights not the stories and pictures.

The Value of Presentation

What does a painting look like? That depends, here are many different way to look at the same painting and each person that views it will see it in a new way. However, the viewer is not the only factor that can be changed to alter the way a painting looks. The environment in which it is displayed is also a very important factor in what the painting looks like even though it is not an inherent trait of the painting. This applies not only to art, but to everything in the world. The way in which something is presented is a key factor in determining how that thing is perceived and understood.

In general, the idea that an object’s presentation can change the way a person looks at that object is not a new or revolutionary idea. It is the reason why people spend so long rearranging the objects in their house until everything pleases their eye. Each of the things that they have in their home looks different in each of the possible place that they could place it, so they keep moving things around to find the places that make every object look the best that it can. This concept can also be seen through the use of seasonal decorations. In December when it starts to really get cold, people fill their homes with decorations to make their homes feel warmer. This is particularly true with Christmas decorations because when you add the tree and all the garlands and lights to a home it fills the extra space in a room with objects that area associated with feelings of warmth and protection from the winter weather. This makes the home itself seem more pleasant to all who enter. In both of these cases people change the way their house and the things inside of it are perceived by the inhabitants and their guests.

Although this seems to make perfect sense in the context of organizing and decorating, when it comes to art this idea has been severely neglected. In general when artwork is displayed anywhere it is done in a very scientific and sterilized way, especially when it comes to two-dimensional art. When it can be hung up on a wall, generally it ends up there alone, with nothing like it within a few feet in any direction. The walls are generally white and boring, they are meant to isolate that single piece of artwork in its spot on the wall so that nothing gets in the way of the viewer seeing that piece and nothing else. Albert Barnes saw this traditional format for displaying art and decided that it was not a very good way to look at art. As he put together his vast collection of art, he intentionally arranged it to go against that formula. He filled his house with art from some of the most famous painters and artists of all time in arrangements that displayed the art in ways that the works had never been seen before. He arranged the art to highlight certain aspect of each piece and connect them together with the pieces around them and the other features of the room (furniture, wall decorations). In a way he made his own artwork out of the works of others. He then created the Barnes Foundation to teach people about his way of viewing art and specifically his private collection.

In his will Barnes clearly stated that his art was never to me moved from the exact location in which he left it, never to be changed. He wanted to preserve his unique way of viewing the art because he believed it to be the only true way to view art. When Barnes died unexpectedly, a whole array of different people tried to sneak past the rules outlined in the will, most were unsuccessful. However, in the end the Barnes Foundation was moved in its entirety from its home in Merion, Pennsylvania to a new location on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Despite the obvious deviation from Barnes’ will, there was a significant effort made to keep the general presentation of the artwork the same. However, these efforts were not enough to maintain exactly what Barnes had created. What the movers didn’t consider is the fact that a part of the presentation of the art is the outside location of the building. Even though the viewer might not be thinking about the fact that they are in Merion or the canter of Philadelphia, it has an affect on their mindset when they enter the foundation that can change their whole experience.

One aspect of the Barnes Foundation that did not change with the move was the arrangement of the paintings themselves and the appearance of the interior of the rooms. The appreciation and understanding of the collection is entirely hinged on this arrangement, there is no other way to arrange the art and produce the same effect that Barnes created. The flow from one piece to the next and the interconnectivity between all of the pieces on each wall and all of the wall together defined the meaning of each painting by the context provided. In any other setting a given painting in the foundation could not bee seen in the same way.

Another way in which people today end up viewing art is through representations of art. Since before the opening of the Barnes there have been advertisements all over Philadelphia about the Barnes that show a representation of one of the paintings in the museum. Besides the fact that this is clearly not the way in which Barnes had intended for the art to be viewed, it is also not the same as looking at the real painting. When you look at the representation you cannot see the brush strokes and the texture of the painting or have the personal experience with the art that is gained when viewing the original.

There are an infinite number of ways to view anything in this world and beyond it. In art, this idea usually only extended to the superficial level of the direct relationship between the specific piece and the person viewing it. Little attention is paid to the relationship between the piece and its environment or the relationship between the environment and the viewer, even though these relationships are essential to the way in which people appreciate art to its fullest. Perhaps Barnes was right in his attempt to perfect the viewing experience of art in that there are ways to view art that truly enhances not only the experience of viewing the art but the art itself.

Revisiting the Magic Gardens

When thinking of critical and deep play, I always come back to the mosaics created by Isaiah Zagar, and the playfully creative impact they have had on the world. They redefined mosaics, and have fabricated one of the most creative outlets of street art. All along South Street his mosaics glimmer in the sunlight, illuminating the numerous fragmented mirrors, reflecting light all around. Words written forwards, sideways, backwards, with many of them relaying powerful messages. The art that Zagar has dedicated his life to is as playful to the onlooker as it is to the creator.

Although I cannot make assumptions on Zagar’s experiences in creating the mosaics, I would hope that through the years of his creations he has had moments of deep play. Explained by Diane Ackerman, “In rare moments of deep play, we can lay aside our sense of self, shed time's continuum, ignore pain, and sit quietly in the absolute present, watching the world's ordinary miracles.” When looking at some of the mosaics that Zagar has created, his passion and playfulness is unmistakable, and allows the viewer to have the same playful and deep experience when viewing his life’s work.

The nature of a mosaic is chaotic and fragmented, but somehow they all work together to create a piece of art that evokes emotions that are original to each and every viewer. Mosaics are abstract in that they are open to every person to create their own interpretations, and I love that everyone who was in the Gardens with me was each having a unique and original experience, although we all occupied the same space. This is the magic of the Gardens; they allow each person to play individually within the playground of art and broken pieces.

Although the Magic Gardens was only the second trip into Philadelphia, this visit to the city was to the most impactful and playful to me, and was my initial look into the world of critical and deep play. I remember walking through the gardens, overwhelmed by the grand quantity of fragmented trash, ceramics, mirrors, and colors that interacted with one another to create a chaotic whole. The art created by Zagar is boundless and distinct from any form of traditional art in that it can be contained to one singular piece of broken ceramic, and can likewise expand to fill a 360-degree space. Each mosaic able to tell its own story, and induce different emotions in its observers, creating a playground from the youngest child to the oldest intellectual.

In looking at the Magic Gardens as a result of critical play we can see the inherent non-linearity that Mary Flanagan describes in “Critical Play,” Zagar creates no set patterns or rules to his art, but rather lets it develop as he works, letting it create itself, allowing for change. The playfulness that is present in his work is an effect of his casual creations that are not meant for critical interpretation. Zagar is “making for making’s sake,” as Flanagan describes critical play artists, and this allows the viewers to experience the mosaics with the same playfulness in which they were created.

I would not go as far to define my experiences viewing Isaiah Zagar’s work as “deeply playful,” but I could see how a deeply playful experience could be derived from his work. It encourages its viewers to think, but not criticize. We accept the art for what it is, and move on to thinking about the emotions this art makes us feel, and the messages it is telling us, whether through words or through images that Zagar has created. This door to an endless variety of thought leads me to believe that at least one person has had a deeply playful experience in the gardens, even if they do not realize it.

The power of Zagar’s work is in its playfulness. Although the art is created through a unique skill, I would not categorize it as art that contains the same meticulous details of a realist painting. This is what makes it special though– it is free and open to more creation. The beauty of his work is that it is unbounded and appears in the oddest of places, always bringing a smile to my face when I see them pop up around a street corner. This playfulness is what makes Zagar’s mosaics special. As I travelled within Philadelphia for the remainder of the trips I always found myself playing in new and unique ways, but whenever I look back, I always regard my trip to the Magic Gardens as the most special. It made me think and taught me how to play meaningfully, impacting me in such a way that I hope to execute the same powerful playfulness in my life.

Culinary Spirit

Culinary Spirit

There was a discovery by British scientists that taste and smell would last longer than visual memories. So today instead of taking everyone to tourist attractions and visit visually, I would like to use the “taste” to approach my city---Chengdu.

I’ve been out of the city for 4 months, and when I closed my eyes, I could still reencounter the taste of the restaurant in front our house. The taste in Chengdu might be the most unforgettable thing in the city.

It is a spicy city, everyone loves spice here, and it somewhat influences the attitude of the residents. Food takes a great proportion in the residents’ life, especially “malatang”. There is at least one malatang place in every block (not exaggerating, there are three in front of my home), and it’s the most representing thing that the city cannot live off.

The idea of malatang actually came out from the boat trackers---their major work is to load goods on ships and travel along the river to deliver. That was usually a whole day travel, so they took the water of the river in a pot, boil with spices and put what they have in there. Then this became popular in the whole district, and people put all kinds of things in it: goose intestine, pig kidney, heart… Those might sound strange for people from other countries or even other province in China, but those are the cheapest ingredients and can create the same delicacy.

There’s a saying in Chengdu called: the best food is hidden in the corner. If you take a walk on a small street of Chengdu during dinner hours, you would probably see people lining up for malatang in front of a small booth. My family used to drive for an hour to get to a famous street corner with only a few chairs to try the famous malatang. And in every district, there would be some places crowded with all kinds of people. The price is cheap (mainly 0.5 RMB per stick) ---partly because of its lower class background, and the low cost of cooking. But all kinds of people come for it: there are expensive cars parking in front of small booths, there are bicycles in the front line, students sitting down for a chat time and also people randomly walk there for takeout. There’s no segregation for food in here, the residents here don’t care that much about the scale or furniture of restaurants, as long as they taste good.

Spices in Chengdu melted the boundary of different classes successfully, because even with different education background and economical well-beings, everyone still shares the same “food culture” living there. It might be for the lower-class brought up the trend of the city that the very cheap street food could bring more pleasure than sitting in fancy restaurants.

However, not many cities are willing to be like Chengdu, even hard to admitted, boundaries are forming the city to advance. The less wealthy would work harder to make them better-off, and the already wealthy people would spend money on educational investment of their children to keep the wealth. And they did all this to pursue a better life status: eat in a better restaurant, live in a better house, and get to a better neighborhood (that’s where American Dream comes from). In Philadelphia, Utah, or any other places I’ve been, I can feel the clear boundaries in the city, the segregation of races made them live in different places and have different restaurants opened in their own closed circle.

But in Chengdu, economical status does not matter that much, everyone can afford to have the city’s taste and feel the recognizable spice for a moment in their mouths. I always believed this city is different, not for the long history or nice weather, but the attitude towards life. The enthusiasm for food broke the invisible walls of rich and poor, old and young, while everyone sits in the same crowded booth with a satisfied smile.

The culinary spirit, the enthusiasm put into food made Chengdu itself a malatang: It has all kinds of different food in it, but the temperature melted the difference, and made it a delicious meal.

Link: http://scienceblogs.com/cortex/2009/11/09/smell-and-memory/

That's All, Folks.

This is a little bittersweet, honestly. I know I probably don’t seem like the type who would get emotional about things, and typically, I’m not, but I’m sad that this is the last paper I get to write for this class. I want to take a breath, even though I just started. It’s a strange feeling. We’re not coming back on Tuesday this time so we can all do our best to figure out what the twenty pages of reading we did actually meant. How am I supposed to explain my issues with Deep Play to my mother? She’s not going to understand. I need fourteen other people to argue with me about it.

I definitely think I’m a different person from the one that started this class. I don’t honestly know if I’m AnotherAbby anymore—yes, when we started class, I thought that was clever and hilarious. There were even more Abbys around me than I was used to, and I already used the name as a gmail account, so it seemed to fit. But, I feel like I’m more than that now. This class sort of bionic (wo)man’d me. We can rebuild her. We have the technology. Coming out of the first writing conference, I was shaken. I’d never gone through something like that before, where someone I respected pointed out to me that yes, I was an okay writer, but I wasn’t going far enough with it. My concepts weren’t great. I hit a good idea near the end of the essay, but I hadn’t gone anywhere with it. And, the scariest part to me was that it wasn’t something I’d half-assed and knew was going to come with criticism. No, I’d actually tried to write that paper. I knew it wasn’t my best work, but it wasn’t until the writing conference that I knew just what I would need to do to succeed: Start over.

So I took the technology of Serendip and I rebuilt myself.

I don’t mean that in metaphysical kind of way. I mean that I had to entirely rethink how I went about my writing process. At first, it was alien to me. I can’t use the format I learned in high school to write papers, with five paragraphs of assertion/evidence/commentary, but I also can’t just talk about my day? Then what’s left?

That was what I tried to work with. What was left. And, from there, I started writing the way I thought was right for the class. That process was messy, and took a lot of trial and error, and I’m still not entirely sure that I’ve worked out how to write the way I think I should, but I think I’m getting there.

The discussion was probably my favorite part of class. I honestly just like hearing people talk, and this was a perfect platform for that, because no one was talking for the sake of hearing their own voice. When we spoke, we had to back whatever we were saying up with our reasoning, whether it be an opinion we hold thanks to a unique experience or an idea that grew out of one of the readings. Personally, I liked when my opinion changed over the course of a class. I guess I was playing the believing game before I even knew what it was, which is probably one of the best concepts I’ll be taking away from this class. I may be a cynic, but in spite of an maybe even because of that, I find that trying to believe wholeheartedly in ideas that are not my own is the best method I can use to see where someone else is coming from.

With that tool at my disposal, I’m not sure where the edges of my learning are now. If I can convince myself that anything someone tells me is right and try to see the world as it would be with that “anything” as one of its components, then I don’t think my learning has edges. I can keep going. If I can see a new world for each and every idea I’m told. I can synthesize what that means, and if I like that world and that idea, I can try to make it happen.

Although, I definitely still have learning edges in subjects outside of what we’ve covered. I know where my edges lie in calculus. That’s kind of the point of calculus.

I’m glad I was placed in this ESem. I know the others couldn’t have given me the same experience, and, as corny as this sounds, I feel like this class was where I needed to be. It helped my writing skills, my discussion skills, taught me reading strategies, and introduced me to Bryn Mawr. It really grew me from AnotherAbby into Abby. And I don’t care if they need to ask me which one I am.

Ruminations on the Class

Well, I’m sure Anne has read a lot of this before. But, I’ll write it out anyway. I love creative writing. It is my passion. Yet, I have never been able to merge analytical writing and creative writing. This class showed me that that is possible. It didn’t teach me that I should quote Sontag and write fiction at the same time. Instead, “Play in the City” showed me that I can be as free in my Creative Writing as I am in my analytical writing.

Or, to use the language of the class, “Play in the City” showed me that there’s no harm playing in my writing, that the times in which I write the best and enjoy my writing the most are when I take risks. Moreover, these risks often pay off. Deep play and critical play aren’t hard to find while I’m writing. Critical play comes far more easily to me than deep play when I am writing because in the past I have felt constrained by structure. But, now as I’m writing this I realize that there is a physical structure to writing. This is unavoidable. The structure I feared was just a mental roadblock. Deep play allows me to go past this roadblock. By the time I’m deep playing, there is no concern over whether I write the word “Penis” or “Headband.” I am only hoping that I’m going somewhere with my writing.

I think a third great thing that this course gave me is the decision to write essays about questions that I don’t have the answer to. This is terrifying. Yet, I think I have often written my worst papers when I have just asserted my opinion again and again and used quotations to support it. This sort of writing doesn’t go anywhere. I mean, what does writing do for an argument that has already solidified in my head? Not much. But, more recently, when I’ve thought about interconnectedness and the Barnes’, I feel quite fearless. This may seem like an exaggeration, but let me assure you. For anyone (including me), it is extremely hard to just write. No reservations. No worrying about what Anne will say or what my classmates will say or (oh my!) what my future employer’s might say. And, this fear hinders my writing. After I take away the intimidation and the roadblocks, I just go. And it feels like joy. Really, I feel quite joyous writing this right now. Some might accredit that to Winter Break and Christmas Spirit. But, I believe that it is thanks to this course.

Early in the course, I did not feel as if the course suited me because I was a sophomore. But, I strongly believe that this course exposed me to a variety of ideas and perspective and it opened up my writing. I am very glad.

rewrite, lucky number 13

There is something defiant about Isaiah Zagar’s mosaics. Cities are built for efficiency, functionality, but not necessarily beauty. Yet, around South Street, a glimmer of light in the gap between two buildings could mean a mosaic of mirrors and color. Upon closer investigation, a pedestrian could find his or herself in a different Zagar’s art is a street intervention, playfully ignoring Philadelphia’s figurative and literal grids to bring subversiveness and spontaneity to its streets.

Isaiah Zagar doesn’t always plan ahead where his next mosaic will be, what it will look like, or where he will get his materials. Many of his mosaics spill across alleyways and onto the back walls of houses, creeping along fence lines as if they’re no longer in the artist’s control. The mosaics fill cracks in alleys with seemingly random words and images. Looking at a map of Zagar’s mosaics is not like looking at a map of a typical art gallery. The mosaics make no distinctive pattern and many do not even appear on the map. In the magic gardens, the route you take is not restricted to a single path. Zagar’s art defies the city’s nearly symmetrical grid pattern in its meandering nature. The art is there “to disrupt the everyday actions in the city” by giving people a chance to think for themselves about what it could mean (Flanagan 14).

Zagar’s mosaics are also intentional. They are deliberate, obsessive acts of subversiveness. Because of the repeating patterns, colors, words, and images, it seems as though Zagar is pointing out certain things to his audience, pushing us to think about the words and images and why he is showing them to us. Using materials like old glass bottles, discarded bicycle wheels, and ceramic plates, materials usually thought of as trash, Zagar redefines what art can be. Hands of all shapes and sizes are prevalent throughout the magic gardens and all of his mosaics, his hands, hands used to create. And from the walls and the ground, eyes of many colors stare in different directions, eyes looking at art from many points of view. Zagar encourages his audience to consider the way society sees art. On one of the walls in the magic gardens, “Philadelphia is the center of the art world” was spelled out with broken pieces of tile. I would usually think of the center of the art world as a museum somewhere in Europe full of historical paintings, but Zagar’s quote undermined that notion, which had been pushed on me by what other people consider important. Philadelphia is the center of Zagar’s art world. I agree with Flanagan that there is a “particular potency in subversive acts through participatory play” (Flanagan 173). Zagar’s work is made to be shared with the neighborhood. By being intentional about putting his art in public places, Zagar allows the public to play and participate in his art and be influenced by his questions about society. A street intervention, like Zagar’s mosaics, is intentional and bold.

My experience in the Magic Gardens was that it was an almost separate world from the street, a street intervention. It was colorful and full of light that had been filtered through green glass bottles, but the mirrors reflected back buildings on either side, cars driving down the street, the sidewalk, and the viewer of the mosaics. I experienced Zagar’s art as a subversive act, because by bringing me into the mosaics, Zagar encouraged me to think of my own relation to the rest of the pieces. I thought about my relationship to all the material things I’ve discarded as I saw similar items incorporated into art. Perhaps this was unintended on Zagar’s part, and maybe no one else in the magic gardens had similar thoughts, but part of what makes a street intervention a street intervention is that it gives its viewers freedom to decide what they want to make of it. It also intervenes in their thinking, and gives them the chance to consider what the artist is trying to ask through the art. Because street interventions are subversive and expressions of ideas, I consider them to be artful as well.

Like Dove Bradshaw and her fire hose, Isaiah Zagar has claimed South Street as his art. He has disrupted it from the grid of the rest of the city using fragments of tile, trash, and mirrors, and he shares it with the people who allow themselves to become a part of the mosaic.

The Beautiful Little Rhomboid

After taking a step back, going home to California and driving to my city (San Francisco), I think the best way for me to end this class is to write an essay lauding discussion-based classes. While I drove through the city, I realized that so much of what we’ve talked about is there: Simmel, Zetkin, and many more. But more importantly, it became clear to me that it wasn’t just Simmel or Zetkin who was correct. They all were. And, they all weren’t.

Steadily, throughout the course, I’ve come to realize something about rightness and wrongness. I’ve written about wrongness before, but this is different. I still love being wrong and being told I’m wrong. But now, I think there’s something bigger than this and perhaps better.

Every day, we would come to class and disagree and agree. Some people would promote the Believing Game. Others would ask us to turn back to the Doubting Game. And slowly, I think everyone realized that it’s not black and white. In fact, few things are. We shouldn’t just scorn interpretation, but we also shouldn’t constantly search for some personal narrative, some greater meaning.

In another class, a week ago, I went on a mini-rant about KONY 2012. I said something like, “This ‘white savior complex,’ it’s ridiculous. Completely. It’s so pretentious to believe that we as Americans can go into another country and fix problems that they’ve been dealing with for decades. They aren’t inept. They don’t lack the resources. The real problem with how our generation romanticizes quick-and-dirty revolutions is that they’re never successful. We simplify people’s complex lives.” Now, I wouldn’t dare compare questions like ‘What is Art?’ to ‘What should we do about Kony?’ But, I think some of the rhetoric I used in this argument is similar. People have been asking questions like ‘What is Art?’ and ‘What is play?’ and ‘What the heck is a city?’ for a long time. That’s because the questions aren’t simple. And, instead of looking for one bright golden truth, we should acknowledge complexity.

For example, the ongoing determinism vs. free will debate. Until I was eighteen, I was sure that I had free will. And then, I found determinism. For two years, I fought for it. Literally, I would argue with countless people over determinism. I would try to sway them with diatribes and words like ‘nature’ and ‘nurture.’ But now, I’m in the middle. You see, I’ve realized that perhaps I don’t care much for THE TRUTH. I’m sure it’s out there. I’ll probably spend the rest of my life pursuing THE TRUTH in many different ways. But, for now, I am content being on the fence about determinism and free will. I realize that what’s truly important about determinism and free will isn’t THE TRUTH, it’s what determinism and free will can give me. Determinism let’s me forgive people. It shows me that poor people don’t equal freeloaders and that there are reasons why people go into a life of crime. Yet, free will reminds me of accountability. Free will dictates that I can’t just go into the kitchen and eat all of the food in the fridge. And, when my parents get upset, I can’t turn to them and say, “Well, I don’t have free will. What else was I supposed to do?”

To turn back to discussion-based learning, this is what it does (when it’s successful). There are people sitting in a room and they talk about things. No one is trying to prove themselves or to prove that their interpretation of Keisha/Natalie is THE TRUTH. Instead, we’re all just trying to learn, to see the complexity.

Often, I let my imagination wander in class. Sometimes a giraffe stands behind Anne Dalke. Sometimes an orb bounces from window to window and lands on the desk of whoever is talking. But, my favorite is when people are speaking and the argument expands before me from 1D to 2D to 3D.

Discussion-based learning allows me to understand, not to suck in knowledge like a vacuum cleaner. I hear many points of view and I am not asked to accept or bad-mouth any of them. Instead, I leave the class with a clear picture in mind: a beautiful little rhomboid, filled with many arguments and many perspectives.

Rewrite: Oh City, My City

When I think of a city, the first thing that comes to mind is skyscrapers and well-dressed businessmen, subways and taxis, Starbucks and a distinct lack of greenery. Cupertino is certainly not a traditional city. But it is a city, an important one. What it lacks in tradition it makes up for in innovation.

Cupertino has none of the elements of a traditional city. We don’t have skyscrapers (in my opinion, an excellent decision given our proclivity for earthquakes). Most of our employers are tech companies, and many employees tend to dress towards the causal end of the business-casual spectrum. Our only public transport is the bus, but most people have their own cars and embrace the California Roll whole-heartedly (in which people don’t stop for stop signs but rather roll slowly through them). And while people do love their Starbucks, they love their Pearl Milk Tea (PMT) even more.

I come from the home of Apple, yes. But I come from much more than that. When I think of Cupertino, I think of sidewalks appearing and disappearing as you walk to school, because half the homes are still small homes from the 60s and the other half are McMansions built within the last 10 years. You can’t walk through Cupertino without hearing at least three languages that are different from your own. Cupertino is the library with fountains outside that kids run through in the summer. Cupertino is Panera filled with students. Cupertino is Mystery Spot bumper stickers. Cupertino is Asian markets and 4.0s and a really terrible football team. We’re a city full of people who were born to be San Francisco Giants fans, and no one can tell us otherwise.

Cupertino is where my friends will naturally switch accents depending on whether they’re talking to their mother or their friends. It is where you have many “aunties,” as we call our friends’ moms. It is where the most popular club on campus is the Bhangra team and where the high school includes a Bollywood number in their spring play set in Cupertino. It is where it is impossible to only have friends of one race. Cupertino is warm. It is sunny. It is closer to the beach than to the mountains, but you could still get to either easily. It is safe. It is a bubble. But it is cracking.

Cupertino is where there has been a bomb threat and a shooting in one year. Cupertino is where people have started to really pay attention to the outside world. Cupertino is where students have started taking charge of their education. Cupertino is changing. It has to. The Cupertino I know was born out of change and must continue to change if it hopes to stay alive.

Because Cupertino is so centered around technology, it works its way into every facet of our lives. People move quickly. The focus in school is on math and science. The majority of the population always has the newest Apple product. The wifi is exceptionally fast. We live close enough to San Francisco that we can visit whenever we want to. And far enough away that we never want to (except for Giants games, as stated above).

Cupertino is different. We have to be, it’s what keeps us ahead of the competition. We’re a city of intellectuals –– but if we want something to happen, we can do it ourselves. And at the end of the day, that’s what we’re proud of: being able to make something out of nothing, and being able to share that with the world. Well, that and the beaches.

final trip

in the final trip of the class, I went out to take the septa with only a sweater and it began to snow in the middle of the train trip. So I changed my original plan of going to Franklin Square. I went to Market East and found a window seat of a tea place, and watched the snowy weather and people outside. There were many people went outside in snow, most of them walked into supermarkets, and some are travelers with suitcases. The shop owners all come out to clear the snow, even it would be covered by snow again later. The interesting thing I found is in the supermarket, maybe it's because it's chinatown, everything is not sold outside US. Even all the pots, chopsticks might appear in US, but everything inside the Chinatown supermarket is having a label tag in Chinese. It come up to me with Barne's segregation of his museum and outside world. It's a segregated world.

re-view of mosaics

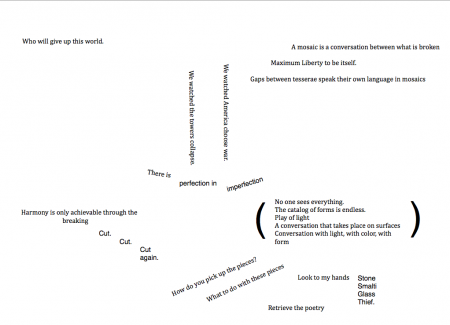

I always regarded the mosaic as fragmented and broken. It is said that“the earliest theory of art… proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of reality.” Thus, whenever I saw the mosaic, I just directly interpret its broken nature as a reflection of our fragmented world, where is collaged by separated people, various emotions and different thoughts. But I forget how magic its connection power is. In other world, I tend to see mosaic as a broken world, but in fact, mosaic itself is a complete art with whole image and expression.

I think the reason is that I’m distracted by the “form” of art. Mosaic is magic because it challenges the way we used to value the art- “whether we conceive of the work of art on the model of a picture or on the model of a statement, content still comes first.” Mosaic is a kind of special art that attracting people first by its form. Moreover, it is the form of mosaic that still causes the interpretation.

When I first visited the magic garden, I thought it’s an artwork, which is collaged by separated parts. People tend to value the mosaic as a broken world. When standing in front of the mosaic, most of my classmates and I see the broken glasses, wheels and bottles. I found mosaic interesting because it is “subversive”. Different from the original art such as paintings hanging on the wall of a museum, it breaks the rule. Thus, mosaic is a kind of critical play-which is defined by Flanagan as “to create or occupy play environments and activities that represent one or more questions about aspects of human life.” It challenges the traditional form of art.

But is it all- a subversive form of art is what mosaic is special about? In other word, recall the experience in magic garden, what we have seen? The broken brick, the mirror that reflects our own image in the art and the separated letters on the wall is not mosaic. We are interpreting the deep and elusive meaning behind the form of mosaic. So what we have seen is not the art itself, but what it is made of and why the artist wants to create this kind of art. We focus on the background and the stories of the art- “wishing to replace it by something else.” What I interpreted in front of the mosaic is that Isaiah Zagar uses the mirror because he wants to encourage people to involve in this broken world, and to some extent, our own world is collaged by separated pieces. I naturally manage the mosaic by pushing my own idea on the art- after all, I become satisfied with my interpretation, acting like an intimate with mosaic who understands all about it.

However, “what matters is the pure, untranslatable, sensuous immediacy of some images.” So mosaic is not only a broken world, more importantly, itself is a complete art. We used to value the art through interpretation-“ a conscious act of the mind which illustrate a certain code… plucking the elements from the whole work.” Thus, what we saw is the detail we especially pay attention to analyze. Without any interpretation and just see the image of mosaic, it is a man, a woman, a dog or a smiling face. The first impression people think about mosaic is that it’s separated, but why can’t we say that it’s only a whole art with portrait of people. Just like we are so get used to the idea of critiquing game-how the mosaic critically challenge the traditional art, we forget to believe the mosaic is still a whole thing, still an art.

Maybe it is the time “to recover our senses. We must to see more, to hear more, to feel more.” So imagine a mosaic is a whole piece of art and do not focus on how it is made, what can we see? It is the sky, the running dog and talking people. Mosaic makes much more sense to us when we see from a full view. In other words, using separated pieces to create art is the method and form Zagar uses but not the mosaic itself. “ In order to understand the esthetic in its ultimate and approved forms, one must begin with it in the raw (Dewey)”. From my point of view, the raw of the mosaic is what really is about and what image is on it. People are so easily obsessed in analyzing and interpreting. Same for the viewer of the paintings in the museum, people tend to analyze the technique artist used when creating and how he expressed a sense of gloom in a portrait when he was not in good health or had no inspiration. But all these transitions are not the pure art itself but the interpretation from viewer.

The mosaics maximize and substantiate the effect of people’s interpretation when viewing art. The distraction of interpretation even prevents people from appreciating what the pure image of mosaic. In other words, it is undeniable that most of the time, what we are doing when appreciating the mosaic is focusing on the broken aspect of the art. It is quite possible that when we talk about the mosaic we have seen, we don’t even know what is it about and what image is collaged. We are not viewing art but thinking. In order to analyze, people can’t see the art, just like kill the goose laying the golden eggs.

The loss of pure appreciation and interaction with arts in returns of interpretation is not what Barnes want either. He doesn’t want people just see the interests and novelty of mosaics’ forms. The most important aspect of mosaic is the direct image and how it is related to the environment, to the wall and to other arts as a whole.

For a real viewer of art, mosaic is complete, not fragmented. It’s a connection, not a separation. Maybe that’s why the mosaic is special- not because of the broken aspects but because it can connect pieces as a whole. Like all arts, mosaic is magic and powerful not because of the separated piece of information, but because of its interaction with and implications to the whole environment in general.

Borders

When you live in a suburb of Cincinnati, you orient yourself by the highways. Get on I-71 and head south into the city. Or you could take a detour on I-275 and take the long way, avoiding the city itself as you drive into Kentucky. However, if you head just a little bit east on 275, you’ll hit Terrace Park, while west will get you to Sharon Woods. Anywhere North and you’re probably heading the wrong way because it’s just cornfields until you hit Columbus an hour and a half later. Let’s stick to the simple things, though, and head South, straight into Cincinnati.

But where does Cincinnati start?

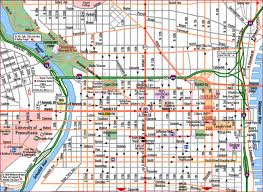

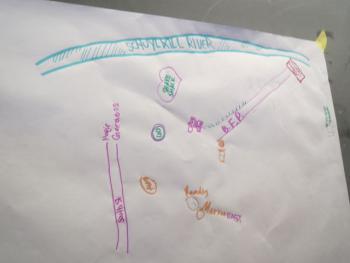

Philadelphia has a border, a river on either side, and a clear, at least from this student’s point of view, delineation between the city and the surrounding areas. Much like the maps we built in class, even detailed published maps use the Schuylkill and the Delaware as the boundaries of the map:

Of course the exact border might change depending on an individual’s approach to the city, whether car, train, bus, or even walking, but that is the nature of boundaries in cities: they constantly shift as the neighborhoods and roads morph over time. In Philadelphia’s case, the subway and other public transit stations probably have a great influence on how commuters see the borders of the city. Indeed, city boundaries are not just concrete lines, but they change both over time and from person to person. Cincinnati is a city that takes this concept way too seriously. It is nearly impossible to find a single, solid ‘boundary’ for Cincinnati. Sure, you can probably try to point out the Ohio River dividing Kentucky and Ohio as some sort of landmark, but even that’s not particularly effective. The city across the river from Ohio, which is technically called Newport, is essentially an extension of Cincinnati. There’s a walking bridge across the water and celebrations and gatherings that span both sides. They are integrally linked socio-economically to the point that only locals would be able to tell them apart. The Northern border of Cincinnati is even more debatable; ask a local (I’m the obvious candidate in this situation), and they might say that the Taft exit off of I-71 is the first exit that will get you into the city. It has the major regional hospitals and a branch of the city’s university, but even that is not the heart of the city. In order to reach what most people would call “downtown”, the hustle and bustle of tall metal buildings and a distinct lack of greenery, you have to travel at least four more miles south. Others could argue that the city extends north of this seemingly arbitrary line to incorporate the largest, oldest, and most famous neighborhoods in the area. Indeed, Cincinnati is not much of a robust cultural and economic center without these neighborhoods included; they contain most of the local restaurants, the small, privately-owned shops, most of the city’s schools, and a lot of the cultural centers. The statistics on the region are most significant here when you realize that the city of Cincinnati (as in the downtown region of concrete blocks and skyscrapers) only has 300,000 residents whereas the whole metropolitan area, which includes all of those neighborhoods has 2.1 million people. Compare Cincinnati to Philadelphia and you see the real importance of this; Philly has 1.5 million people in its downtown region and 6 million in the entire area, which means that a quarter of the population of Philadelphia lives in downtown whereas only a seventh of Cincinnati’s population does the same. Cincinnati cannot exist as a city independent of the large neighborhoods that might be considered by some as ‘outside of city limits’. To simplify: Cincinnati is suburbia with a mini-metropolis in the middle, while Philadelphia is a towering metropolis surrounded by suburbia.

However, they are such different cities that a comparison to find out which one is the ‘better’ city is unfair to both of them. It’s like trying to decide which one’s better: A giant panda or a red panda. They both are labelled as pandas, they both share some of the most obvious features (four legs, snouts protruding from rounded heads, and circular ears stuck on top), but they are two entirely different species. They do not even belong to the same family and are only distantly related. The same is true of cities because they are each their own separate and unrelated entities. It seems so easy and simple to call Philadelphia the better city because it’s bigger, grander, more cultured or some other such nonsense, but for every massive market like Reading Terminal, Cincinnati has a Findlay market. For every history museum snug on the parkway, Cincinnati has Union Terminal Museum Center. For every Philly cheesesteak cart, Cincinnati has a Skyline chili. For every Rittenhouse Square, a Fountain Square. You want to compare size? The Public Library of Cincinnati has more books than Philadelphia’s Public library even though Philly is three times the size of Cincinnati. Size means nothing, particularly among two cities that are fundamentally different. Cincinnatians don’t go into downtown to meet at a café and chat with friends, they go five miles North to Hyde Park and wander down to the Coffee Emporium nestled among all of the neighborhood’s free-standing houses. Not to say that Cincinnati does not have its pitfalls: there is no public transportation system to speak of, but that is just one more thing that makes the city what it is. I’m no urban theorist, but without public transportation, everyone needs to independently commute, which means that everyone has cars. That is one of the reasons the city is so spread out among its suburban neighborhoods, because everyone has to commute anyways, so they tend to live farther away in a balance between the smaller population density and longer commute. Philadelphia on the other hand has the wonderful SEPTA, which is beloved of all car-less college students and shuttles thousands of people to work every day.

Now I know it seems circular to make an argument against comparisons by doing one myself, but the point is that the differences (e.g. population size, restaurants, types of museums, etc.) do not make one city better than the other, but simply makes them different. Furthermore, the identity of a city is constantly morphing, building upon itself, recreating itself using the incessantly changing people that live both within and without its limits. The people are unique and the cities that house them are unique. As I return home to Cincinnati tomorrow, I take back with me the knowledge of the city not just as a metal and concrete, but as a living creature capable of extraordinary things.

Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. United States Census Bureau, n.d. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. <http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/42/42101.html>.

Road Map of Philadelphia. AccessMaps.com, 2007. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. <http://www.aaccessmaps.com/show/map/us/pa/philadelphia_overall>/.

Thomas, G S. Census: Cincinnati 57th-largest U.S. city. Cincinnati Business Courier, n.d. Web. 19 Dec. 2013. <http://www.bizjournals.com/cincinnati/stories/2010/06/21/daily22.html>.

[Re-write] Being A Participant in Art -- Discussing with Kaprow And Sontag

Before my trip to the Old City, I thought it was the spectator that made the picture. But this recent experience helped me realize that it was not that simple. It is not only the audience makes the picture, but also the performer, the creator and the artwork. These elements together make the "participants", who are actively engaged in the art or playful activities and jointly infuse dynamics and diversity into the work. The art is not complete without either the artist or spectators. A work engenders its true meanings with its participants. This also corresponds to Sontag's article on Against Interpretation. We should learn to "see more, to hear more, to feel more".

This point was perfectly illustrated in my trip this weekend. On our way back, we ran into a piece of mosaic by Isaiah Zagar in an area that was not fairly close to the Magic Garden. Even if we were rushing for the train, we still stopped there for a while to take a clearer look. Located at the entrance inside an art school, the mosaic was still a shining piece for all of us. Because we had participated in Isaiah's artwork, had tried to find the beauty in every corner of his Magic Garden, and had quietly had a wonderful "conversation" with him through the shimmering art pieces. We were amazed at coming across his mosaic, but the women who sit outside the entrance looked at us strangely and wondered why seeing a colored wall made us so happy. Those women were merely spectators, unlike us. We engaged in Isaiah's work, therefore we were able to fully appreciate this amazing serendipity and understand the importance of this piece. Our joy was not due to the content of this piece of art, but because of feel the form and true self of it.