Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Objectivity, Measurement and Psychiatry

“Humans are themselves natural phenomena” (Barad 336)

Psychiatry has evolved tremendously as a field in the previous centuries; it was not until the mid nineteenth century that psychiatry began to be recognized and organized—to an extent—as a medical practice. Now in the 21st century, medical practitioners specializing in the field of psychiatry must operate at within the tenuous intermediary position between the social and hard sciences, the result of which has been the drive of scientific and social energies into new and exciting directions. Despite its evolution, modern psychiatry is still not without its critics most of whom raise ethical questions regarding patient care: in a field increasingly more fixated within the natural sciences, is patient care and treatment maintained at a high enough, even ethical, level? A group of critics have emerged under the heading “anti-psychiatry” expressing these concerns; it has become increasingly apparent that in order to prevent the social aspects of the field from being undermined by the scientific ones, psychiatrists must tread carefully between the scientific and social approaches.

Barad’s objectivity: a unique approach to scientific inquiry

In her chapter entitled “Quantum Entanglements: Experimental Metaphysics and the Nature of Nature”, Karen Barad introduces a fascinating new approach to scientific methodologies within a new framework of understanding the nature of reality. Barad’s conceptualization of measurement, objectivity and agential realism presents a radically new approach to scientific inquiry, an approach which would be helpful to keep in mind while analyzing current methodologies and practices in various scientific fields, including the field of psychiatry. Framing an analysis of psychiatry—its history, development and the role of women in the field—with Barad’s concepts in mind will help to elucidate the implications of the field’s past and current problems, and, perhaps, introduce an alternative approach for the future.

Barad begins her chapter by reflecting on the traditional scientific approach, commenting: “the tradition in science studies is to position oneself at some remove, to reflect on the nature of scientific practice as a spectator, not a participant” (247). In this introductory reflection Barad refers to the role of the observer or measurer in a scientific experiment, stating that the tradition is to place the observer at “some remove”, at a distance, from the phenomena which he/she is studying. This approach places the measurer as a “spectator”, as one who watches and makes observations separate from the phenomena. Barad is careful to note that this renders the observer as one who merely watches, but does not actively with the phenomena. In response to this traditional approach Barad posits a new model of scientific inquiry: “…scientific practices must be understood as intra-actions among component parts of nature and that our ability to understand the world hinges on our taking account of the fact that our knowledge-making practices are material enactments that contribute to, and are part of, the phenomena we describe” (247). Here Barad introduces her notion of “intra-actions”, suggesting some sort of interactive co-participatory relationship between the two members of the experiment, namely the observer and the observed. In this view the observer is not a spectator in the experiment, but rather a part of the nature he/she observes. Here Barad critically addresses her notion that our “knowledge-making practices”—the way humans understand the world through observation and experimentation—are “material enactments” which both “contribute to” and are a “part of” the phenomena we observe. In this sense our observations contribute to the very phenomena we are observing and we ourselves, as observers, are intrinsically part of that nature we are aiming to understand through observation.

In her new model of scientific inquiry Barad defines two important experimental factors within the framework of her new understanding: measurement and objectivity. She argues that “what we usually call ‘measurement’ is a correlation or entanglement between component parts of a phenomenon, between the ‘measured object’ and the ‘measuring device…” (337). Here she defines measurement as the combination, or “entanglement”, of the observer and the observed. Just as the observer is part of the nature he/she is attempting to understand, through measurement he/she becomes entangled with the very phenomena he/she is trying to describe. Barad references Bohr, whose theory of objectivity is more in line with her own: “Bohr argued that it is possible to secure the notion of objectivity in the face of quantum nonseparability because objectivity is not predicated on an inherent of Cartesian cut between observer and observed, but rather what is required for objectivity is an unambiguous and reproducible account of marks on bodies” (337). Einstein believed that objectivity was predicated on the separability between the observer and the observed. Unlike Einstein, however, Bohr argued that separability—in the sense Einstein viewed it—was unnecessary to preserve objectivity. Rather what was necessary was that the object being measured left “unambiguous” and “reproducible” marks of effects for the observer to see. In this sense, the observer and the observed could be entangled because separability was not necessary to observe objectivity. It is this understanding of objectivity and measurement which allows Barad to conclude that the human observer is not separate from the phenomena he/she observes, but is entangled with the object of observation. The human “seeks to understand the emergence of human along with all other physical systems”.

Underlying Barad’s notion of objectivity and approach to scientific inquiry is the notion that the measurement of a natural phenomenon involves the entanglement of the observer and observed. Quantum mechanics is related to this theory that the very act of measurement alters the presentation of the phenomena, the experimental conditions impact the result. The notion of measurement and objectivity is integral to any science, and may in fact be useful in examining the field of psychiatry, its development and the implications for its future. Because psychiatry involves the study of human patients it seems this notion of measurement would be even more applicable to this field. The model of observer/observed can be applied to the dialectic of psychiatrist/patient. If Barad’s model were applied however, that would suggest some type of “intra-action” or “entanglement” between patient and psychiatrist. The notion that once something is measured, its natural state or manifestation is somehow altered or changed can be directly applied to psychiatry. This concept is very similar to the social concept that when people are observed they act differently.

Psychiatry as a discipline: a brief history

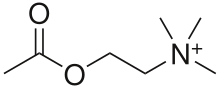

The number of insane asylums increased drastically in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth century. The first psychiatric hospital in the United States was built by Anna Marsh (Doctor’s widow) in 1834. Although there we some asylums and psychiatric institutions in the seventeenth-nineteenth centuries, it wasn’t until the twentieth century that psychiatry really developed into a medical field with a biological/anatomical approach to understanding mental disorders. The biological approach to psychiatry began with a new understanding of a network of “nerves”, which eventually led into other neurological based fields such as neurology and neuropsychiatry. Freud’s psychoanalytic therapy permitted patients to be treated in private practices rather than the public asylums. However, as early as the 1970s the field began to move away from the psychoanalytic method. One of the first major breakthroughs was Otto Loewi’s finding of the first neurotransmitter: acetylcholine. This breakthrough begins the close interplay between psychiatry and psychopharmacology. As early as the 1980s neuroimaging techniques become utilized to examine functional patterns in the brain. All of these developments in the late twentieth century allowed for the increasing scientific focus in the field which was beginning to implement a number of scientific methodologies—neurotransmitters (neurology), neuroimaging (physics), psychiatric medications (involving a number of scientific approaches), influence of genetics (biology). Psychiatry quickly became more associated with the biological sciences and less with the social sciences. It is precisely this movement away from the social and into the realm of the hard sciences which has raised recent criticism about deterioration in patient care and treatment, suggesting that the loss of the social approach has been a disadvantage to the field. acetylcholine

<- Otto Loewi & Acetylcholine ->

Neuroimaging

Women in psychiatry: a brief history

This elusive intermediary position between the hard and social sciences seems to be one of the most important issues in modern psychiatry. Considering the necessity to tread a boundary between these two dialectical approaches raises questions concerning the field as it stands now: who composes its practitioners and the methods and practices of these doctors. The notion of a binary between the social and hard sciences may be related to issues and stereotypes which arise within the binary established between male and female psychiatrists. In order to assess the role of women in psychiatry and the current implications within the field for gender and treatment, it would be helpful to see the hstory of women in psychiatry as both patients and doctors.

Gender played a substantial role in the early stages of psychiatry. The Victorian notion of domesticity ensured that those women who rejected this lifestyle were committed to asylums. The author of an article “Women and Psychiatry” argues that the “cornerstone of Victorian psychiatry claimed male dominance was therapeutic. The doctor ruled the asylum like a father ruled his family.” In this sense the long established patriarchal structuring of the asylum—and the consequent subordination of women patients—may have some correlation to the modern gender binaries within the field and the general approach to psychiatry as being less sympathetic and compassionate (traditionally female characteristics) and more domineering and objective (traditionally male characteristics).

Dorothea Dix

Dorothea Dix played an indispensable role in arguing for the rights of those in asylums and improving the conditions of the institutions. The majority of doctors considered women “more fragile and sensitive than men” (“Women and Psychiatry”) making them predisposed to mental instability and breakdown. The characteristics and behaviors used to describe the diagnosis of “hysteria” were most often found in women patients, and those men who were diagnosed were appropriated as “feminine” men. A woman displaying symptoms of hysteria was often recommended to treat it by marrying. As the author of this article notes these gender typical stereotypes persisted into the 1960s and 1970s.

Interestingly, it was during this period in the late twentieth century when the field saw a sudden increase in the number of female psychiatrists. It was also during this time, as the author of an article “history of women in psychiatry” Laura D. Hirshbein notes, that the field of medicine began to receive criticism for its overly scientific approach at the expense of compassionate, sympathetic human approach to treatment. The women who began to earn degrees and practice this profession frequently asserted that entrance of women in the field of psychiatry would make a difference: it was the participation of women that would restore the lost human, sympathetic approach. It is interesting to note that it was the women themselves—who by entering the field began to break the gender binary—that paradoxically asserted the benefit of their participation to be the traditional female characteristics of heightened emotional intelligence and compassion. Additionally, during the 1970s women psychiatrists began to be requested by women patients.

Hirshbein also reflects on the professional difficulties of women who historically had a difficult time advancing within their respective field. This is especially true of women within the medical profession. The author is careful to note that the simple increase in the number of practicing women psychiatrists in the field may not have been enough to break the gender binary and perhaps the preformed notions and stereotypes of women still remain as impede women’s achievement in the field; instead, what’s needed is a complete reassessment of the role of women within this field (341). Hirshbein suggests that women should take on pedagogical roles with the field of psychiatry acting as role models of female psychiatrists.

Modern Feminization within Psychiatry

In an article entitled “The feminization of psychiatry: changing gender balance in the psychiatric workforce”, Wilson and Eagles review a couple of studies concerning gender differences in the field of medicine, particularly psychiatry. The authors reference one study (Rey et al, 2004) which suggested that female psychiatrists experienced fewer patient complaints, legal threats and other negative patient outcomes than men, but the authors are careful to add that some studies have shown a higher incidence of work-related stress (Rathod et al, 2000). The authors suggest that perhaps women are better at dealing with difficult clinical scenarios and cases but are more emotionally impacted by the experience.

Another common assumption is that women chose to go into psychiatry precisely because it is more suited to family life. The authors of the article reference studies which support this notion that women are more likely than men to choose careers based on how they will impact family life. As the study Goldacre et al, 2005 suggested, the field of psychiatry has better hours and work related conditions. The authors also note the historically inferior merit achievement of women (less likely to be awarded) and that in general females are underrepresented among faculty at medical schools, and tend to have lower rankings.

Issues and Implications for the field:

In their article “The female psychiatrist: professional, personal and social issues”, Dora Cohen and Elaine Arnold reflect more directly on gender issues within the field of psychiatry and their implications for the field. In the article they refer to a study (Goerg et al, 1999) which suggested that “gender-based constraints may be leading female psychiatrists to work shorter weeks and show less diversification in their clinical activities and to refer more frequently to the psychological model rather than the biological model” (82). This suggests that the gender binary within the field may be perpetuating the differences in between male and female practitioners: in this sense the female psychiatrist characteristics—working shorter hours, appealing to psychological as opposed to biological models—may be a result of the historical gender stereotype in the field.

In his article “When Women Rule Psychiatry”, H. Steven Moffic reflects on similar issues and their implications. In the article he reflects on a talk he went to by a Dr. Cassell which suggested an intriguing possibility within the field of medicine. He writes: “She went on to wonder whether the social forces of male power, the rise of evidence-based medicine, and increasing time constraints make the expression of compassion more difficult for all physicians” (1). In this sense Dr. Cassel attributes the lack of compassion and sympathy in the medical field to the residual “social forces of male power” and the increase in the hard scientific approach to medicine. Towards the ends of his article Moffic interestingly reflects on the notion that perhaps “socialization cause[s] [women] to be like the men they succeed—especially if they need to adopt male values to rise to the top” (4)? In this sense the social history and structure of the gender norms and binary within the field may only serve to perpetuate the “male” approach in medicine, particularly psychiatry as one which is evidence-based, objective, and wholly scientific. Because males dominated the field of medicine for so long, perhaps the structure of the field itself is imbued with these male dominant characteristics, suggesting, as Moffic does, that in order to succeed all students—male and female—have to adopt these traditionally “male” characteristics. Moffic posits that perhaps a change in leadership style, one that is focused on “care and nurture of colleagues and patients” would make a difference (4)

Ultimately, taking Barad’s quantum entanglement into account it seems that the most effective approach is some combination of a social and scientific approach within the field of psychiatry. A field which is divorced from the social sciences may lose its humanistic touch and social approach to problems within the field, whereas a field divorced from the hard sciences loses medical credibility and scientific validity. The centuries long battle of the social and scientific domains within psychiatry have naturally lead to a false dichotomized approach to the field. The implications of the social vs. scientific approaches are related to the gender-related issues within the field of medicine—where the overly-social approach tends to be traditionally associated with females and the wholly scientific approach tends to be traditionally associated with males. The current statistics on the achievement gap between men and women in the field are directly related to the issues within the field regarding the best approach. Because it is not fully tied with the hard sciences it becomes stigmatized as a less rigorous—if not more “female” suited—field, yet a complete alienation from the social sciences would result in an overly scientific compassionless field, which doesn’t seem to lend itself to effective psychiatry. Barad’s approach to entanglement and objectivity suggests great implications for the future of scientific inquiry. Just as Barad’s entanglement theory breaks down the barriers between observer and the observed, perhaps the boundary between hard and social sciences should be broken down to allow for a more entangled methodology within the field of psychiatry. Furthermore, applying Barad’s model to the psychiatric model, is it possible for the observer (psychiatrist) and the observed (patient) to be in a more entangled state? Could not the psychiatrist maintain objectivity in the Baradian sense which still ensures understanding of the observed phenomenon? In the combined social and scientific field that is psychiatry it seems a Baradian break down would be most effective to ensure an objective process of measuring human phenomena.

Works Cited

Barad, Karen. “Quantum Entanglements: Experimental Metaphysics and the Nature of Nature”. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press, London: 1997.

Cohen, Dora and Arnold, Elaine. “The female psychiatrist: professional, personal and social issues”. Web. 31 Mar. 2011. <http://apt.rcpsych.org/cgi/reprint/8/2/81>

Hirshbein, Laura D. “History of women in psychiatry”. Web. 31 Mar. 2011 <http://ap.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/28/4/337>

Moffic, Steven. “When Women Rule Psychiatry”. Web. Mar. 201. <http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb4345/is_3_36/ai_n29426743/pg_3/?tag=content;col1>

“Psychiatry”. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychiatry#Early_modern_period>

Wilson and Eagles. “The feminisation of psychiatry: changing gender balance in the psychiatric workforce”. Web. 31Mar. 2011. <http://pb.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/30/9/321>

“Women and Psychiatry”. Web. 31 Mar. 2011. <http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/themes/menalhealthandillness/womanandpsychiatry.aspx>

Comments

entangled practitioners

An excellent thesis--could Barad's work help to elucidate the implications of the nature of the field of psychiatry on its current tensions, and perhaps introduce a new approach for the future. You go on to exemplify this with the gender wars in the field mapped onto two embattled conceptual definitions of the field: the biological and chemical hard sciences and the more whole-person-centered social sciences.

You raise very engaging questions. I was left wanting to know more about your thoughts on how you might answer them. How are patients and psychiatrists entangled? What are the consequences of such entanglement?--advantages, disadvantages? What might the new approach actually look like?

Your writing raised for me a question that has broader implications. How are the power dynamics of a field entangled with how a field progresses and is shaped? Your description of the field of psychiatry reminded me of the climate in the physics profession, specifically, the adaption to the dominate culture to succeed. Been there.

p.s. I wondered about the choice and use of your figures--did you mean for them to reinforce a point in particular? You might address them in the text to flush that out.