Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

What is Tiger Mother Really About

There is no doubt that “mother” is one of the most valuable and influential figures in our society. She plays a vital role within the traditional family structure, which is part of our social fabric and is at the core of our culture. However, many of us do not expect that being a mother would make me more of a feminist. In fact, we fear quite the opposite, worrying that feminist convictions would wane under the weight of overfilled diaper bags and the expansive responsibilities of caring for children. I therefore wondered the correlation between motherhood and feminism: Are they compatible? What is the effect of a feminist parenting? Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother by Amy Chua, though may not give me answer to the questions, at least provides me with some interesting hints.

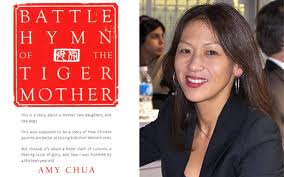

The week that Amy Chua’s book was released, she became one of the most provocative women in the United States because of her relentless, driving way of parenting. Chua’s rules for her girls include: no sleepovers, no playdates, no grade lower than an A on report cards, no choosing your own extracurricular activities, and no ranking lower than No. 1 in any subject. (An exception to this last directive is made for gym and drama.) Everyone held the same belief—Amy Chua is a mean, mean mother. But we cannot neglect that fact that she indeed achieved great success on both her career and child rearing. After obtaining her J.D. from Harvard Law School with GPA 3.9, she is now a professor at Yale Law School. Her first book, World on Fire, which was a New York Times Bestseller, gained a worldwide recognition and got selected by The Economist as one of the Best Books of the year. As a mother, she also made some enviable achievements. Her older daughter Sophia is a piano prodigy who played Carnegie Hall when she was 14 or so. The second daughter, Lulu, is a gifted violinist. In Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, Chua never disguise her sharpness, writing frankly her method of mothering. It seems that Amy Chua, as a determined, assertive and extremely successful working mother found a great balance between feminism and motherhood.

Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother appealed to me right from the start, because the book is strong as a global feminist text. Chua writes about the experiences of her grandparents, parents and herself in this intergenerational, transnational memoir. She is writing about herself and her daughters, of course, but it’s more than that. She’s writing about assimilation and her desire to remain connected to her Chinese immigrant heritage. Realizing that she is unable to raise her children exactly the way she was raised—Chua and her husband are quite professionally successful and have the ability to raise their daughters with a great degree of class privilege which Chua herself did not receive as a child—she opts to emulate the rigor with which she was raised, which includes an overbearing emphasis on schoolwork and perfect grades, demanding extracurricular activities and a minimal social life.

I do not want to make any judgment about if the way that Chua used to raise her daughters is correct or if Chinese mothers are superior to Western mothers, because no outsider can know what their family is really like. As her older daughter Sophia wrote in the letter to speak out in defense of her mother, “They don’t hear us cracking up over each other’s jokes. They don’t see us eating our hamburgers with fried rice. They don’t know how much fun we have when the six of us — dogs included — squeeze into one bed and argue about what movies to download from Netflix.” As Chua reiterates in her book, Chinese parents “assume strength, not fragility” in their children, and therefore demand more of them, setting higher standards, assuming they can handle more pressure in the name of high performance, or at least good behavior. It turns out that she is right—Sophia and Lulu are walking to their bright future as Chua expects. In the letter mentioned above written by Sophia, she expressed her thankfulness to her tiger mother: “now that I’m 18 and about to leave the tiger den, I’m glad you and Daddy raised me the way you did.” This is a happy story for real, in which both the daughters and the mother get what they want.

Nevertheless, it is true that Amy Chua’s tries to design intentionally the lives of her daughters, rather than letting things happen naturally. Her logic follows that her success came from overcoming all the difficulties and growing strong under the pressure that her parents imposed on her, so her daughters will be successful as well her if she creates the same environment for them. In my perspective, the biggest disadvantage of such feminist way of parenting is that it blocks other possibilities for children to live, including the possibility to fail. The mother, as a mature adult, knows what is widely valued in the society, so she carefully premade many choices, including what instruments to learn and what classes to have. Then the children were pushed hard to be the best in those choices made by the mother. Once they succeed and taste the sense of accomplishment, they will become self-motivated, and things will be much easier. Such punishingly hard work — enforced by parents — yields excellence; excellence, in turn, yields satisfaction is what Chua calls a "virtuous circle." This strategy is hard to dispute, because it ensures all things will end up with endless success.

But is it fair when being success become the only possibility of life? Don’t children also need failures? Amy Chua doesn’t think so. "In Disney movies," she says, the [studious kid] always has to have a breakdown and realize that life is not all about following rules and winning prizes, and then take off her clothes and run into the ocean or something like that. But that's just Disney's way of appealing to all the people who never win any prizes. Winning prizes gives you opportunities, and that's freedom — not running into the ocean." However, don’t failures also give you opportunities—opportunities to be strong and rise from failures? If feminist is about giving women and girls equal opportunities to choose and experience the life they want, then obviously that Amy Chua’s model fails to do so.

More generally, I also feel that Amy Chua’s view on issues in a too binary way. Chua unnecessarily and unfortunately reinforces this artificial distinction between “Chinese/Asian” and “American.” Parenting does not have to be an “either-or” proposition — there does not have to be a rigid line drawn between “rigorous” and “permissive” styles, nor does there have to be a complete separation of “Chinese” and “American” styles. Chua does not seem to give much credence to the possibility that many Chinese Americans and Asian American parents do both — combining the best elements of the different cultures with which we’re familiar. In fact, this is just another example of the kind of “transcultural” assimilation that Asian Americans have done ever since they first arrived in the U.S. It is understandable that as a daughter of Chinese immigrants, Amy Chua understand that as a racial minority in American society, she need to push her children a little further to make sure that they are able to overcome some of the hurdles and barriers that stand in our way when it comes to socioeconomic success and full institutional integration into American society, especially in tough economic times when competition for jobs and other resources is even more intense and potentially filled with racial tension. Yet in this age of globalization, the need for advanced educational and professional skills in order to stay competitive in the global marketplace is readily apparent and increasingly stressed by almost everyone from all backgrounds.

I do like Amy Chua’s book, because it functions as a starting point for dialogue about bigger issues such as feminist-parenting techniques, the maintenance of one’s cultural heritage and the importance of potential over ability. Never once does the tiger mother declare that she chose the best method of mothering. She doesn’t make excuses for her actions, but she doesn’t ignore the massive problems they caused, either. And I think Chua should be respected for the choices that she made. Does that mean she’s free of mistakes? Of course not. Though she made both herself and her daughters become representatives of successful modern women, the lack of freedom in her parenting method and the closeness in her binary view of the world cannot be neglected. I appreciated Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother for its honesty and its ability to open a dialogue about parenting and cultural heritage, feminism and motherhood. Now it’s time for that dialogue to begin.

Comments

Correlating Motherhood and Feminism

melal--

Many of your classmates created webevents this month that offer comparative analysis of feminist issues in different geographical locations (see, for ex, An Issue Transcending Borders), whereas others (most particularly and distinctively, just speak nearby/working towards ideas) challenged the usefulness of marking our experiences according to geographical borders: "our labeling of feminisms as rooted in some national identity/location/region can have the possibility of flattening and erasing nuance from how feminists express themselves in a variety of contexts."

Your work here, in its attentiveness to what you call “transcultural assimilation," also refuses such geographical boundaries; doing so is part of another intellectual move that has become very important to your thinking: that of refusing binary constructions in any formulation of a problem. I saw you doing that, last month, in your analysis

of dating game shows and feminism in China, when you focused on a key problematic highlighted by one particularly popular show: however outspoken the women contestants may be, the game they are playing is still simply one of "catching" a man (and yet, you add: how poignant the need and desire to do so!).

This month you turn your attention to a similarly complex phenomenon: how to correlate motherhood and feminism? What modes are most helpful in helping children to flourish? "Winning prizes gives you opportunities, and that's freedom" is Chua's strong answer to that question: "punishingly hard work yields excellence; excellence, in turn, yields satisfaction," because "it ensures all things will end up with endless success."

Your analysis of Chua's book, like that of If You Are The One, is measured and balanced; I'm particularly struck by your highlighting Chua's assumption of "strength, not fragility" in her children, and by your observation that she intentionally "designs" their lives, rather than letting things happen naturally--which "blocks other possibilities for children to live, including the possibility to fail." This reminds me of an article by Paul Tough that we looked @ together last semester, which argued that what kids need for "a happy, meaningful, productive life" is to " learn how to fail."

That Chua's model "yields excellence," on the one hand, but fails, on the other, to give her daughters "equal opportunities to choose and experience the life they want," is certainly a feminist conundrum. Perhaps the main questions your essay begs, though, are "What counts as success?" How to measure a successful life? Who gets to say what makes any individual life a success? What form of assessment can possibly pass such a profound judgment? Is success "staying competitive in the global marketplace," by acquiring "advanced educational and professional skills"? You say, towards the end, that Chua "doesn’t ignore the massive problems" caused by her parenting methods. What are they? (I mean, the ones she acknowledges, not those you foreground….)