Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Speechless: Language, Gender, and Sexuality

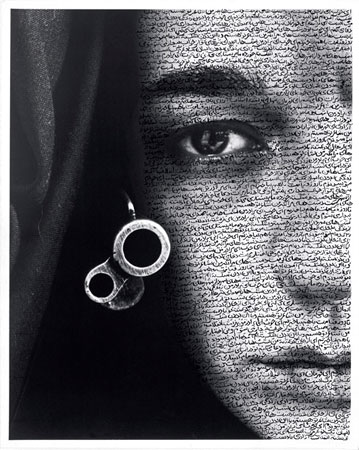

Speechless, Shirin Neshaat (1996) source: www.artstor.com

Growing up, gender and sexuality were topics rarely discussed. Sure, exclamations of “you’re so gay” were rampant and words such as “pussy” were used to belittle men, but neither of these expressions were ever deemed problematic because issues of gender and sexuality were never talked about. If anyone did have a problem with it or wanted to bring up these topics, they were not allowed. Each year one student tried to establish a gay-straight alliance, but each year the school administration denied her proposition in that it was too “controversial.” I remember her well: she had short hair, didn’t shave her legs or armpits, and was referred to as “that lesbian.” I think she was the only openly gay student who ever went to my school. It didn’t help that she was a self-proclaimed feminist and therefore was ridiculed further. It was not that people had a problem with her sexuality, but the topic was avoided to the extent that we did not have the language or the means to discuss it. It was taboo. We did not even realize that some of the things we were saying were offensive! Interestingly enough, I maintained this sense of the fluidity of gender and sexuality, although I did not have the theological knowledge or language to express how I felt about issues of gender and sexuality or even a place to talk about it.

When Sherry Ortner visited our class, we talked about the “shock” of coming to Bryn Mawr. For me, it was not so much a shock, but more of an emergence from a dark, suffocating cave. I felt as if this heavy weight had been lifted and I could feel free to talk about the issues that interested me, which were often of gender and sexuality. I noticed fliers in dining halls advertising talks about LGBTQ issues, films about pornography and prostitution, and seminars around issues of safe sex. Diverse representations of femininity and masculinity existed as well as openly straight, gay, and trans people. I found myself in a community in which gender and sexuality were discussed in passing, at meal times, in the lecture halls, and I began to build a vocabulary in order to describe what I saw and felt.

I found myself eager to learn more about the dynamics of gender and sexuality. I wanted to understand what it was about these topics that made it so taboo growing up, yet so accepted here. So, I began to take classes.

My gender and sexuality education began with an art history class called, “Women, Feminism, and the History of Art.” We looked at art history from a feminist perspective, focusing on representations of the female body throughout history and how these representations reflected the views of women in popular culture. I learnt how to critique a work of art with a feminist eye by analyzing paintings and reading feminist critiques. I understood the strong relationship between woman and body- the obsession, even, with portraying a woman’s sexuality. I became aware of the differences between an artist and a woman artist, the “real” representations of women versus the distorted, over-sexualized representations, and the duality between the ideal woman being exotic and primitive, yet innocent and pure. Reflecting upon the class now, and recalling McIntosh’s system of education, I find that much of the curriculum was in stage 3. We acknowledged the lack of women in art history as problematic. We described what we saw, the lines, the movement, the color, the shapes, and usually came to one conclusion: the rampant objectification of the female form. But, I found that our education pretty much stopped there. We came to these broad conclusions about perceptions of women in art, yet never discussed the broader discourses surrounding gender representation that contributed to these depictions. Even though the subject of the matter was quite progressive considering most art history classes which are typical still in McIntosh’s idea of stage 1, it was surprisingly conducted in a very traditional manner. Each day we looked at slides of art work as the teacher lectured about what the paintings meant establishing a relationship in which the teacher knew everything and the student, nothing.

When I came across an introductory class to gender and sexuality, I felt like it would help me answer some of my more philosophical questions around gender and sexuality: why do these categories exist? What do they mean historically? Through readings of Hegel, Freud, Sacher-Masoch, Krafft-Ebing, Butler, and Irigaray (and many others) I gained a philosophical and theoretical understanding of gender and sexuality. I learned how ideas of patriarchy and sexism developed in history through descriptions of gender relations and sexual behavior in fiction, psychology, and philosophy. Yet, I found that while we read all these historical and interesting texts, we often never related it to the modern world. We never questioned if the interpretations by the authors were relevant today or even why we were reading each text in the first place. We simply read, discussed, and moved on. By the end of the course, I understood key terms such as hermaphrodite and transsexual or asexual , but did not really know what to do with this information.

At the same time, I was also taking a class which analyzed the broad structural problems that contribute to the “other-ing” of non-western nations and the establishment of ideologies of masculine, more powerful and therefore, morally superior countries as opposed to their feminine, weak, and morally backwards counterparts. What I enjoyed most about this course was how we used feminist theory to describe the structures that exist today, often using our observations and our experiences to formulate arguments. We discussed capitalism and neo-colonialism and how they contributed to the gendering of nations as well as issues surrounding prostitution and gendered labor. I learnt about gender and sexuality in how it contributes to the construction of transnational structures, policies, and relationships.

Looking back on year one of my gender and sexuality education, I find that discussions and readings often revolved around culture’s ideologies of gender and sexuality as a discourse as opposed to the individual’s construction of it. I never thought to question my own constructions of gender and sexuality until now. In reading texts from multiple disciplines such as biology, anthropology, and literature, I learnt not to simply accept the author’s interpretations and opinions, but to question them and relate their theories to my own understanding of gender and sexuality. Especially in reading The Doll’s House, a work of fiction by Neil Gaiman, I have begun to think about the unconscious and dreams as a constructor of meaning. We often put so much emphasis on society and how society constructs ideas of gender and sexuality, but rarely look to the world of fantasy and literature as a discipline to be taken seriously. In literature, there is the possibility for countless interpretations. Each reader reads the text in a different way and can relate on entirely different levels because of our individual historical and social locations. Sure, we can analyze each word the author uses and why, but what is most important is how we each formulate thoughts and dreams.

Furthing this emphasis on the self and the constructs of gender and sexuality, I have begun to think critically about language and how it contributes to our formation of thoughts and ideas. I have thought a lot about what I want to get out of this course on gender and sexuality and have found that a unit on linguistics would be exciting and interesting. I am fascinated by the idea of language as either a limiting or liberating force. Are we constricted by language because everything is put into distinct categories or can we use language to free ourselves from constricting societal structures? Does thought proceed language or language proceed thought? Using linguistical theory as a base, we can begin to ask questions such as whether language is intrinsically sexist, if there is specific gender-associated language, or even sexuality-associated language. Does our language change depending on the identity we take on? I recommend that we start off with some basic linguistic theory such as the work of Derrida and broaden our discussion of language by reading works such as Kiesling’s “Power and the Language of Men” and Land and Kitzinger’s, “Speaking as a Lesbian: Correcting the Heterosexist Presumption.”

Continuing our focus on language and how it relates to thought, I also thought it would be interesting to look at how our thoughts and interpretations are affected by different mediums. We have already touched on this a little bit by discussing the significance of a graphic novel as opposed to a novel, but I thought it would be interesting if we looked at how our discussions would change depending on if we were talking about a text, a film, or a painting. Is there more freedom of expression and interpretation in one as opposed to another? Are we allowed more freedom to dream and interpret in a novel that lacks pictures, or a film that “shows it all”? A film I thought would be interesting to watch in our class is “Jules et Jim” because it plays around with complicated gender roles and has an interesting twist. It is also a French movie, so the idea of translation from the original form could be something to be discussed as well. Lastly, in order to take these discussions of language and gender and sexuality outside of a purely academic sphere, I thought it would be interesting to do exercises and projects that explore different mediums. For example, instead of writing a paper about our experiences with gender and sexuality, we could make a silent film or create a slideshow of pictures to convey our thoughts or feelings without the use of language. Would it be more liberating or constricting? Are we more affected by the visual or the textual? Then we could relate this back to issues of gender and sexuality by examining the relationships between language and the reproduction of gender inequalities and the (mis)representation of reality. Must we be problematizing our language or our individual thoughts in our effort to more accurately discuss gender and sexuality? Are we, as women, speechless as the photograph suggests? All these questions (and more), I am interested in discussing.