Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Alison Bechdel's Fun Home - Repetitions of Disability & Queerness

I'm particularly interested in exploring Alison Bechdel's (2006) Fun Home in the context of my independent study because it explores issues of both disability (Bechdel has suffered from obsessive-compulsive disorder, or OCD since the age of 10) and also queerness (both Alison and her father are gay).

Some ideas that I've been exploring throughout the text:

- How might the form of the text itself (a graphic novel) mirror the way in which both disability and queerness are managed in the book? Alison attempts to control her escalating anxiety through compulsive behaviors just as her father is attempting to control his own sexuality. Do the images in the text, each contained in separate boxes, come to highlight this desire for containment, to not let the supposed “otherness” (anxiety/queerness) leak out? The maps that are placed throughout the book also seem to provide a certain safety to Alison and her father by providing them with control. In her Wind in the Willows coloring book, for example, Alison’s “favorite page was the map” (146).

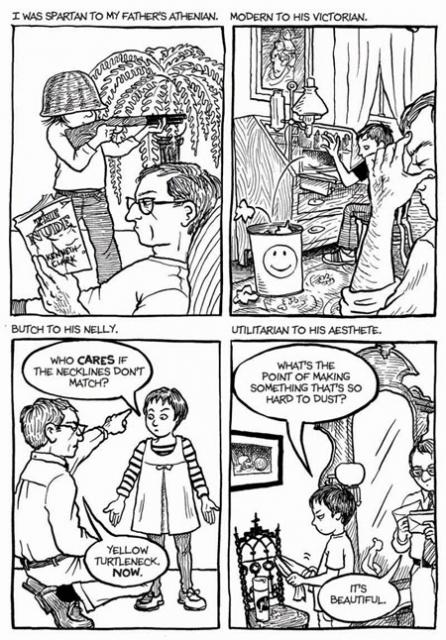

- Importance of repetition? Bechdel’s compulsions (some of which include counting, replicating specific behaviors that she believes have positive effects, wiping away “the invisible substance that hung in doorways” (135), repeating specific phrases, lining up her shoes perfectly to ensure that both of her parents are safe, kissing her stuffed animals, and writing “I think” in between words and phrases in her diary) are obviously repetitive, but so too are her father’s attempts to contain his homosexuality (taking care of the garden, tending to the family’s home, ensuring that his daughter look feminine). After all, Judith Butler theorizes gender as “a stylized repetition of acts." How is the text itself a performance of identity? Do all the references to literature and fiction serve to highlight this performance? Alison and her father both come out to one another through the medium of the Colette book that her father had given Alison. Does fiction become a medium for understanding reality?

- In the image above, Alison's father is inflicting his own compulsive behavior in regards to gender onto his obsessive-compulsive, but also queer daughter. He wants the necklines of her dress to match so that she appears "feminine", whereas she opts for the mismatching colors in an attempt to reject the confines of femininity. It is here that her father appears to have more symptoms of OCD than Alison herself. Queerness and disability become interchangeable.

- Alison is very much intent on trying to understand the relationship between herself and her father. She seems interested in the “affective” relations of the preposition “besides” that Eve Sedgwick discusses in Touching Feeling. What happens when these images of both herself and her father (both exploring their queerness) exist side by side? What might the white space, or gap between the images do for Bechdel in terms of sexuality? In her 1993 Tendencies, Sedgwick writes, “That’s one of the things that ‘queer’ can refer to: the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically” (8). Bechdel seems very much concerned with the "gap" throughout the texts--specifically the gap between herself and her father who share so much, yet remain so far apart. Bechdel comments on her fear of thresholds (doorways, for example) when she was younger and suffering from severe OCD and I see this threshold as making the line between “disabled” and “non-disabled”, between “queerness” and being “straight”, between “reality and “fiction”.

- Truth also plays a significant role in the text. Part of Bechdel’s OCD revolves around her fear that she’s not being truthful or that she can't accurately depict what has happened on a given day (which is why she makes marks over particular words or phrases in her diary to signify her uncertainty). She writes, “How did I know that the things I was writing were absolutely, objectively true?” (141). Perhaps this relates to one of my previous posts, where I questioned whether or not Kay Redfield Jamison’s memoir “An Unquiet Mind” accurately or “truthfully” portrayed her battle with manic-depressive illness? Because of the intensity of the doubt that her OCD causes her, Bechdel loses a sense of who she is; her OCD, in a way, causes her to lose her identity. In Fun Home, queerness and disability are less about labels (or particular markers of identity), then they are about a disruption of identity, a loss of self. My question then becomes: do queerness and disability come to reject identity? (Interestingly, in his book No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Lee Edelman writes, "For queerness can never define an identity; it can only ever disturb one" (17)).

Comments

Discussion with Anne: Repetition and Fear

Anne and I came up with a really interesting way of bridging this idea of queerness and disability. I talked a lot in my post about how OCD becomes a way to manage queerness in Bechdel's Fun Home and we came to the conclusion that the repetition associated with both OCD and also gender (as I mentioned in my post, Butler defines gender as "a stylized repetition of acts") stem from fear. The repetition associated with gender comes from a fear that there is no gender binary or essential gender and the repetition only serves as a means of enforcing gender categories. The repetitive rituals or compulsions of OCD are an attempt to lessen anxiety in hopes of controlling what is uncontrollable. So, both gender and OCD are about attempting to manage the uncertain world through repetition. And in a way, this repetition aims to create a fictitious world--one that is neat and contained--rather than one that is real and disorderly (which goes back to Bechdel's playing with fiction and reality).