Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Sex Workers’ Rights: A Call for Decriminalization

*Sex workers can be male, female, intersex, trans*, genderqueer, or otherwise, and exist in every corner of the world, but for the sake of this web event I have focused on female sex workers in the United States.

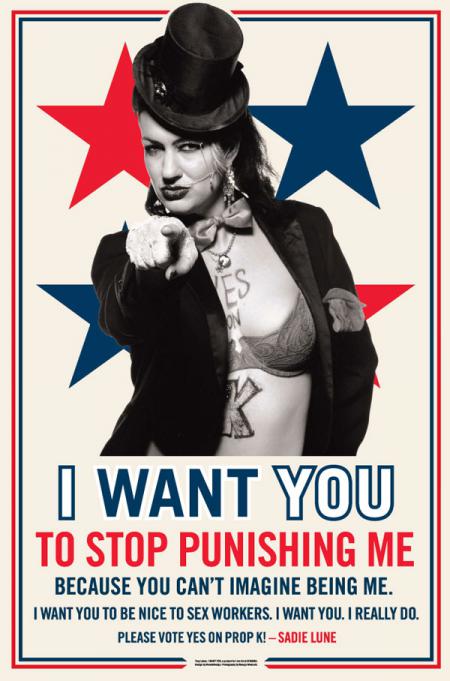

This web event proposes potential goals for sex workers’ activism and outlines many of the challenges to achieving these goals. Due to the polarizing nature of the subject, a sex workers’ rights campaign would need to address both social and political components. A solely political project, without address confronting seminal issues of stigmatization and discrimination, would struggle in garnering support and would unlikely improve the actual lives of sex workers. Exclusively cultural change would fail to protect sex workers under law and would give implicit consent to the current legal system that regards sex workers as second-rate citizens.

Currently, in the United States, prostitution is illegal throughout the country, except in a few counties in Nevada in which regulated brothels are legal. In contexts where prostitution is legalized it is often met with strict governmental controls and regulations, which dehumanize the sex workers and deny them agency rather than protect them. Laura Reanda, in her article “Prostitution as a Human Rights Question: Problems and Prospects of United Nations Action,” critiques this regulationist system because it “entrenches the notion of prostitution as a necessary social service performed by a separate class of women” (Reanda 203). She similarly dismisses the criminalization of prostitution because she believes it has largely manifested itself in “police harassment [that] does not end prostitution but drives it underground, increases the power of pimps, and contributes to the psychology of violence against women” (Reanda 203).

Additionally, an ideological shift towards the fight against the traffic in women has produced laws that necessarily demote sex workers to second-class citizens by restricting their basic human rights, such as free movement across borders. These anti-trafficking laws have serious repercussions for all undocumented sex workers because fear of deportation prevents the reporting of crimes or injustices. The political stronghold of trafficking discourse allows the larger issues of economic disparity and need to go unaddressed. As long as prostitution remains an economically lucrative option and when unemployment or low-wage work are the only other alternatives, individuals will continue to choose sex work.

Ronald Weitzer explores the “failure” of the prostitutes’ rights groups in the 1970s in the United States in his article “Prostitutes Rights in the United States: The Failure of a Movement.” He focuses his analysis on the sex workers’ rights group COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), which he argues failed despite emerging in an era defined by its welcoming environment of social change and sexual exploration and acceptance. He compares COYOTE with the relative success of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) movement to argue that a call for the legalization and regulation of prostitution needs much more than the moral support of the immediate community, a tall order itself, but also requires sufficient resources of money, facilities and labor that are often provided by a backing third-party (Weitzer 24). He argues that, among other factors, the gay rights movement benefited from a preexisting sense of group support that was fostered by the shared space of gay bars, an element missing from the prostitutes’ foundation. Weitzer’s data about the very small percentage of prostitutes nationwide that are members of COYOTE reaffirms the need for allied support. Unfortunately, a relationship with the women’s movement, the most obvious choice for a backing third party, was fundamentally difficult to create and sustain because of the deep theoretical divide within the movement about prostitution and the fear of contamination by the “deviant” status of prostitutes.

Although they didn’t have much “success,” as defined by Weitzer, their stance on decriminalization stands today. COYOTE calls for decriminalization because the current illegality fosters client brutality by forcing prostitution underground and to the margins of society and discourages prostitutes from reporting abuse. Additionally, COYOTE acknowledges that there are moral objections to the sale of sexual activities; however, they believe that morality should never be regulated by the state, but should rather be matters of individual choice (Paterson-Iyer 27). An acceptance of sex work as legitimate in the mainstream consciousness would require either a rejection of state regulated morality, as advocated for by the members of COYOTE, or radical changes in the mentality and of the masses.

In the chapter “Depicting Prostitutes Under Patriarchy,” Russell Campbell uses a Freudian platform to address many of the underlying gender issues that drive sex work. According to Freud “the man almost always feels his sexual activity hampered by his respect for the woman and only develops full sexual potency when he finds himself in the presence of a lower type of sexual object” created because “a strong incestuous fixation in childhood...requires [the boy] to repress any erotic impulse towards his mother in order to avoid transgressing the incest taboo” (Campbell 24). Men suffering this psychical impotence “could be sexually excited only by a woman whom society regarded as degraded: the woman of loose morals, in particular the prostitute” (Campbell 25). In other words, good women resemble the mother and cannot illicit sexual feelings, while ‘bad‘ women are viable objects of sexual attraction. Shulamith Firestone, quoted in Campbell, argues that this theory is projected from individuals outward onto the larger society and whole classes of women are categorized as either good or bad. Firestone extending this logic, argues that “a critical result of this psychological process is an alignment, and often a confusion, of erotic and violent impulses directed toward the “bad” woman, which may explain why the prostitute so often becomes the substitute target for the hostility of the frustrated male” (Campbell 26). And because the lowered status and general disposability of sex workers is upheld by the entire society, not just by the frustrated male, they are an easier target, and there are fewer consequences for their rape and/or killing, than women who society deems “decent.”

There must be strong efforts to combat the stigma around prostitution and to promote the understanding that women who perform sex work are not intrinsically different than anyone else. Sex work is a job for sex workers—not a defining personal characteristic. However, currently, sex workers face extreme marginalization from mainstream society and lack of reintegration into the public sphere after retirement from sex work. Reanda argues that once entered, prostitution is incredibly difficult to leave due to a combination of “overt coercion and physical abuse, but more frequently the result of emotional blackmail, economic deprivation [and] marginalization” (Reanda 205). Our society is uncomfortable with the idea that women can perform sexual acts for pay and not be damaged or innately different from the women who society accepts as decent. It is threatening to men within a patriarchal society to accept that the same women who gave birth to them, marry them, and raise their children could choose to prostitute themselves, without coercion, because of economic pressures.

Wendy Chapkis, in her article “The Emotional Labor of Sex,” argues that sex work is not any different from other emotional labor such as childcare or psychotherapy, traditionally gendered occupations that do not carry the same stigma as sex work. She dismisses the portrait of the emotionally damaged and unadjusted prostitute who’s “soul is in necessary and mortal danger through the commodification of its most intimate aspects” (Chapkis 71). Instead, Chapkis commends sex workers for their skilled ability to accurately guess what their client wants and then to subsequently use deep acting to convey the appropriate emotions. In the same vain, sex workers learn strategies of distancing, disengagement, dissociation and disembodiment that allow for the separation of their work from their self.

The aforementioned critical divide within the feminist movement around issues of prostitution is simplified into two camps, liberal/contractarian and domination/subjection, by Karen Paterson-Iyer in her article “Prostitution: A Feminist Ethical Analysis.” In short, liberal/contractarians believe that sex work can be an equal contract between two consenting adults in which an exchange between sexual activities and money occurs. On the other hand, supporters of the domination/subjection mentality believe that prostitution necessarily entails male domination over females and is in turn inevitably detrimental to women.

The liberal/contractarian mentality has been espoused above through the works of COYOTE, Wendy Chapkis and Laura Reanda. The work of Kathleen Barry, a leading anti-prostitution feminist, fits easily the domination/subjection mentality. In her seminal article “The Prostitution of Sexuality,” Barry does not distinguish between explicitly coerced prostitution and prostitution per se. She argues that all prostitution is the “fullest patriarchal reduction of woman to sexed body” (Barry 22). This abolitionist mentality dually disallows constructive discourse about the actual lives of the prostitutes as well as any discussion about the socioeconomic context that created the necessity to enter sex work in the first place. Barry’s model also permanently relegates prostitutes to an all-encompassing victim status, which discredits their own agency and devalues any actions they are already taking to improve their own lives and working conditions.

For More Information:

Two Contemporary Coalitions:

International Prostitutes Collective

Sex Work Activists, Allies and You (SWAAY)

How you can help:

Works Cited:

Barry, Kathleen. "Prostitution of Sexuality." The Prostitution of Sexuality. New York:

New York UP, 1995. 20-48. Print.

Campbell, Russell. "Depicting Prostitution Under Patriarchy." Marked Women: Prostitutes

and Prostitution in the Cinema. Madison: University of Wisconsin, 2006. 21-40.

Print.

Chapkis, Wendy. "The Emotional Labor of Sex." Live Sex Acts: Women Performing

Erotic Labor. New York: Routledge, 1997. Print.

Peterson-Iyer, Karen. "Prostitution: A Feminist Ethical Analysis." Journal of Feminist

Studies in Religion 14.2 (1998): 19-44. Print.

Reanda, Laura. "Prostitution as a Human Rights Question: Problems and Prospects of

United Nations Action." Human Rights Quarterly 13.2 (1991): 202-28. Web.

Weitzer, Ronald. "Prostitutes' Rights in the United States: The Failure of a Movement."

The Sociological Quarterly 32.1 (1991): 23-41. Web.

Images:

http://pizzadiavola.files.wordpress.com/2008/10/sadie-lune.jpg

http://blogs.laweekly.com/informer/swaay%20billboard.JPG

http://www.prostitutescollective.net/ecplh.jpg

Comments

bodies of alliance

Venn Diagram: thank you for this thoughtful and well-researched analysis of continuing efforts to decriminalize and destigmatize prostitution. By including posters, red boxes to demarcate sections, bolded conclusions, and links to further resources and modes of action, you've made a visually strong and compelling web event. I also like how you've channeled Barad here and diffracted this issue through history and psychology!

Your elaboration of the pyschoanalytic foundation of the Mother/Whore binary was clearly articulated and highlighted the ways in which the psyche begets social discrimination. It also deepened my understanding of why COYOTE's movement did not gain political traction even in the culturally transformative 60s and 70s. I remain curious about what is going on in the US today with COYOTE or other organizations. I appreciate the need to focus a 4-page paper, but the "global" leaks into your US-centric analysis as you bring in issues of human trafficking across our international borders and SWAAY's petition that addresses the murder of sex workers in the UK. Since many (most?) sex acts cross boundaries between bodies, it seems inevitable that sex work would cross boundaries of nation states.

In thinking further about how economic pressures can lead to sex work, you might want to return to Paul Farmer's analysis of how structural violence reduces economic opportunities for marginalized people and how these pathologies of power lead to poor health outcomes. Your recognition that we need both political and cultural changes to improve the well-being of sex workers is on target. However, one challenge in confronting these larger structural issues is how to address the immediate needs of people who are suffering within the current webs of power. This is where I see the importance of the public health strategy of harm reduction, which gives us a way to provide support for individuals while also working to change policies and cultural perspectives. (When I checked out SWAAYs website, I saw that harm reduction was an important element of their work. Is it also a key dimension for other groups? And one other thought: what about women with other options for sustaining their livelihoods, who freely choose sex work as their profession? How do they figure into considerations of structural violence?

By situating sex work within the larger sex industry ("- which includes movie directors, club owners, webmasters, retail stores, and more - but are distinct because their job involves making money off of their own sexual labor, not writing about, photographing, managing, or selling the sexual labor or performances of others") you drew my attention to ways in which corporations, but not individuals, are protected from prosecution within our society. Because most sex workers are female and the majority of movie directors, club owners, etc. are male, the targeting of sex workers, but not these corporate entities, also highlights how sexism permeates our political and economic systems.

I also wanted to comment on your statement that "sex workers learn strategies of distancing, disengagement, dissociation and disembodiment that allow for the separation of their work from their self" and note that this happens for many others, including emergency workers, health care providers, social workers, police, etc., who need to distance themselves from the trauma that they encounter and not let their work hemorrhage into their personal relationships. I'm puzzling over how these common modes of denial (distancing, disengagement, etc.) prevent us from recognizing our shared precarity as humans and, therefore, restrict our willingness to build alliances.

bodies of alliance

sorry for the double posting--i just erased this copy