Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Children’s Books and Graphic Novels: One Genre, Different Names (Extended Version)

Children’s Books and Graphic Novels: One Genre, Different Names (Extended Version)

Reading is part of the life and the act of reading can be divided by the stages of our literacy. These stages are visual literacy, language literacy, textual literacy and analytical literacy. Visual literacy is the ability to interpret images and symbols in a given environment, textual literacy is the ability to read (aloud or not) a given text and describe it and analytical literacy is the ability to go beyond what is written and analyze it by dissecting it to find the core meaning of each phrase, the intentionality of the author or to simply compare it to other texts etc. The first stage (visual literacy) begins when parents read picture books to their children and goes on to the following stage (textual literacy) with chapter books once the reader is old enough to read on his or her own. For a number of years graphic narratives have become a part of an emerging genre eagerly read by young adults and mature audiences depending on the subject. Scholars are paying close attention to graphic narratives and the way images and text complement each other. Like children’s books, graphic novels would not achieve their purpose of telling a story in a clear, concise and innovative way if images were not there to enhance the meaning of the text. With this being said, I believe that we have been reading graphic narratives since childhood; the only difference is that they are known by different names based on the stage of our lives in which we read them. The books we were read as children are known as a children’s book, the ones read by adolescents (adults at times) are referred to as comic books and the picture books read individually by adults have been given the name graphic novels by the scholarly community.

As a bilingual student, I will analyze a children’s book I was read to in Spanish and another one in English and share my experiences versus reading Persepolis a decade later.

Images in children’s books are essential to the narrative because children have the tendency to pay a great deal of attention to them mainly because they are not yet capable of reading on their own. Children develop their imagination and the ability to identity objects and their colors, moods and emotions by just looking at images before they are able to speak and read text; they develop their visual literacy. As said by Lee Galda (University of Georgia), in the article Visual literacy: Exploring art and illustrations in picture books, “ children need the ability to see in the fullest sense to recognize the significance of what they are seeing” which allows them to develop their insight that eventually makes them visually literate individuals.

Taking Galda’s statement, it is essential to establish which are the elements children’s books should have in common. Illustrations must have relatable characters such as animals or children close to their age to explain the situation the child might be facing (picture books are often used to explain it in a way kids can understand). For children, reading picture books is an act of communion, they depend on someone else, most likely a parent or family member to read to them. As children grow older, there may be a disconnect between them and their parents, or whoever read to them because the next step is the development of their textual literacy, by reading chapter books that makes them grow out of the habit and need of being read to.

Growing children not just grow out of this habit but also tend to forget about their visual literacy, which affects them during their adulthood. Once we are past the stage of being read to, we enter the stage of textual literacy. We as readers are trained to read words, not pictures. Thomas Forster’s book How to Read Literature Like a Professor mentions a special kind of reader Foster refers to as a “professional reader.” A “professional reader” pays close attention to symbols and patterns in literature. We are trained to go beyond what is written on the page and become “professional readers” that the importance preserving our visual literacy has diminished. It has become harder for us as readers, especially the younger generations, to interpret images by themselves and accompanied by a small amount of text because textual literacy has been prioritized over visual literacy. After striving to become “professional readers” we polish our proficiency with time. It is often thought that those who are polishing their reading skills (critical thinking) proficiency are just young adults, adults can also benefit from becoming better readers. Thinking about what being a visually literate individual entails, I believe that my generation is visually literate, not just literate enough to interpret images with text with confidence and deftness since visual literacy is not prioritized. We are presented with images in multiple platforms like web pages and television and most of us seem to grasp what is being presented but not engage in critical analysis. Nowadays, young adults and other adults may face this situation but not in the scenario of the children’s book. For instance, we see images, people or cartoons interacting amongst each other and they may be talking which means their dialogue must have been text at a given moment. Images are shaping the 21st century way of learning, visual literacy is becoming as essential as textual literacy and very soon both will be of equal necessity.

For those adults who have not enriched their visual literacy as much as their textual literacy, it is much harder to think critically of any image. Unlike small children who loyally abide by their adult reader’s insight, these adults have to regain their visual literacy on their own, passing their own judgment on whatever illustration they encounter.

We have found the object to use to teach children how to be visually literate but the approach as to how they should be taught that concept is still being debated. Due to the fact that a child’s first interaction with a book involves an experienced adult, it should be the adult’s responsibility to be proactive and explicit in the process and control and mediate the situation. This way the adult can enrich the reading experience and the text that is being presented to the child. The books should serve as a tool to explain a child a particular situation so that the adult can jump off from what the book says and possibly elaborate what the text says (in terms of acquiring a solid vocabulary) provide a forum for any questions during or after the reading and even ask the child questions. Being an explicit reader is also essential due to the fact children learn what to identify what is and is not important based on what the adult tells them.

Art is an efficient method of communication, after careful examination of the illustrations; the adult reading aloud can pinpoint the multiple things that may be going on in the image as a whole or the stories inside the pictures themselves. A good skill to implement once the child is familiar with picture books, is the ability to anticipate and identify the outcome of a sequence of illustrations put together. These skills can apply to native speakers of English and those children learning it as a second language simultaneously with their native tongue. In short, visual literacy is universal. Years of reading picture and chapter books and recently graphic novels have allowed me to come to these conclusions.

There is a certain novelty in picture books because the reader can write the story the way he or she wants to, provide a new caption for the image. These books normally have a picture and very little text. The image depicts the literal thing (s) that is going on, and the text reinforces the meaning of the image. This reinforcement allows for the image to provide information the text does not, its job is to contribute something new to the narrative. To make myself clear, I will use the analogy of the supplementary and complementary angles used in Geometry. The supplementary angle is that one that adds up to 180 degrees and the complementary adds up to 90 degrees. The supplementary angle relies on the complementary angle in order to add up to 180 degrees. In conclusion, the text in picture books rely on the illustrations in order to get the point across efficiently.

To prove my point, I have chosen two children’s books that are very dear to me: Mi mamá, Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) and Mo Willems’ The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog!

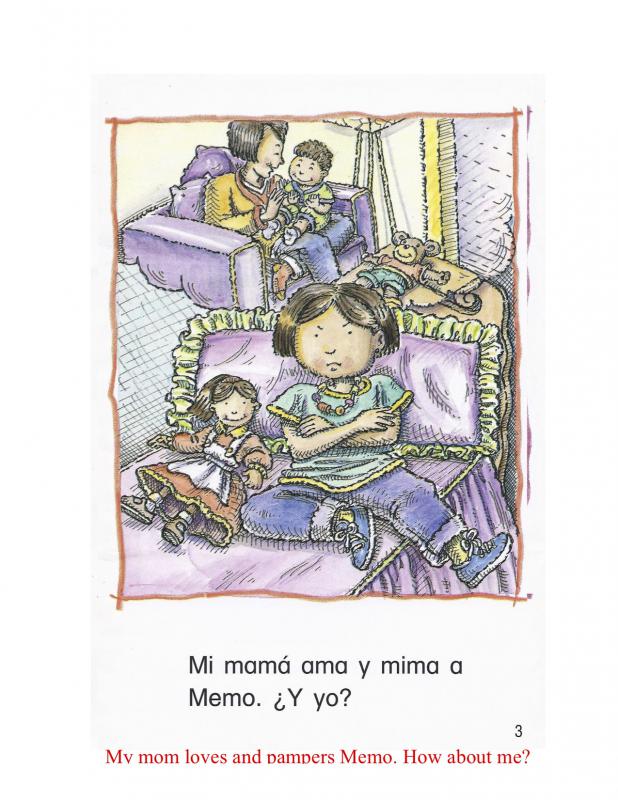

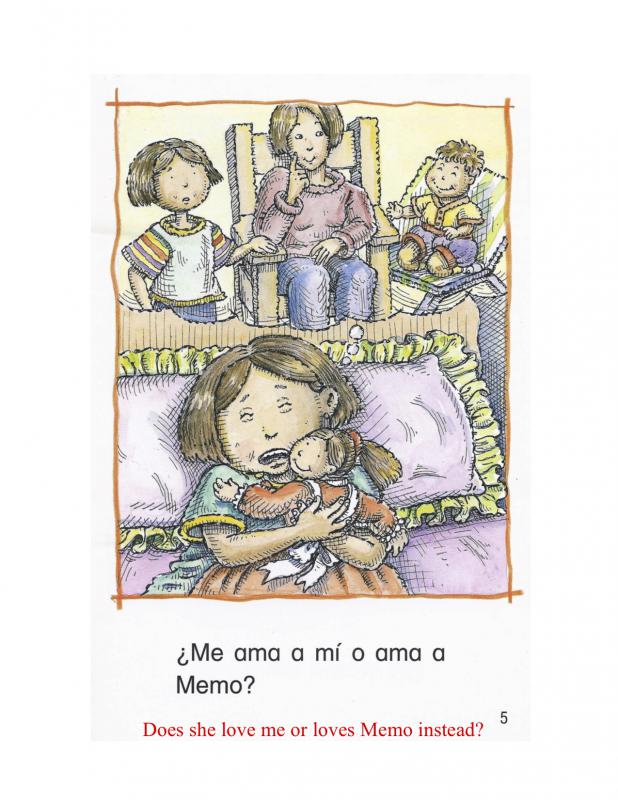

Mi mamá, Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) is a short story narrated by a young girl, this is why the title includes an “I”, who struggles to accept that she is no longer an only child. The author, Wanda De Jesús- Arvelo, was given the challenge of creating a short story by only using words that had the syllables ma,me,mi,mo and mu and the words "yo" (I) and "ayudo", (first person present tense of the verb “to help”). Having accepted the challenge, De Jesús- Arvelo, had to make sure her story was coherent and understandable for parents and children that are going through that particular situation, however, she knew her story was missing the key element that would help get the point across effortlessly: illustrations. With illustrations that go beyond words, the child can clearly interpret anger and distress and see the reactions that come as a consequence of acting that way. This can also apply to Mo Willems’ The Pigeon Finds a Hot Dog! On the first page the reader knows the pigeon is excited about finding a hot dog:“Oooooh! A hot dog!”, I must add that the person reading to the child is most likely to know that an exclamation mark indicates excitement. The child now knows what being excited sounds like but he/ she may not know how to react towards excitement. It is important for the child to see the image that is with the text because that is the only way he/she can perceive the notion of being excited. The pigeon shows he is excited by vigorously flapping his feathers to the point that some fall off. After seeing the image and hearing what the pigeon says, the child can identify the reader’s tone of voice and vigorous repeated movements with being excited over something.

The reading of images is not only pertinent to children who have not undergone the training of reading text, it applies to adults as well. Many adults who have preserved and enriched their visual literacy are not only attuned to images in graphic novels and their topics but editorial cartoons that criticize society in a humorous manner. Editorial cartoons are great for those adults trying to regain visual literacy due to the fact the address topics such as politics. Images with these connotations have been part of a tradition of communicating a message that is often a critique to an element or individual in society aimed for mature adult audience that has often experienced what is being criticized. Magazines like Time and The New Yorker are known for their cartoons. For example, the ones featured in Time magazine are mostly concerned with politics whereas the ones in The New Yorker include a variety of topics like politics, family and business etc. Below is an example from The New Yorker magazine.

The illustration above shows a critique that employees(ers) lack originality and do not “think outside the box”; the fact that a submissive animal represents the employee that quietly listens to its owner’s (boss’) instructions. It is much easier for an adult to make similar interpretations due to the fast he/she is visually literate and therefore, knows about the circumstances behind each image and can associate certain images with certain situations. This exercise showed me that it is essential to apply Foster’s idea of what a “professional reader” is into our visual literacy because those patterns and connections can also be made with images. Becoming a “professional reader” of both texts and images leads to the thirds stage of literacies, analytical literacy which requires lots of practice.

Scott Mc Cloud (Understanding Comics) addresses the premise that children do know what a comic is from an early age, they simply refer to it by a different name. In comics artists also appeal to the reader’s emotions, when reading Persepolis, there were times a times where I was able to gain a better understanding of what the author was trying to say if I read the image and the text individually and them the two of them together.

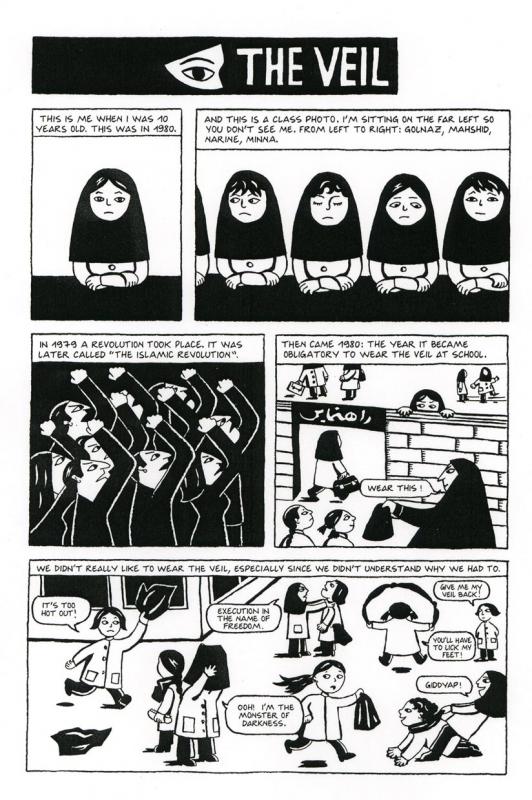

When I last interacted with children books, I was read to and mostly paid attention to the images that when put in a particular sequence told a story and not the small of text that accompanied each image. Compared to Persepolis, the experience reading it was different because my maturity as a reader has evolved since I last read those children’s books. In terms of content, the topics presented in this graphic novel are meant for a more mature audience due to the fact it deals with Marjane Satrapi’s trials and tribulations growing up during a war in Iran and defying a society’s beliefs etc. The difference between Persepolis and the children’s books previously mentioned is that Persepolis includes pictures and text divided into panels. There are numerous short stories compiled into two large volumes that make up most of Satrapi’s life whereas a children’s book only has one story.

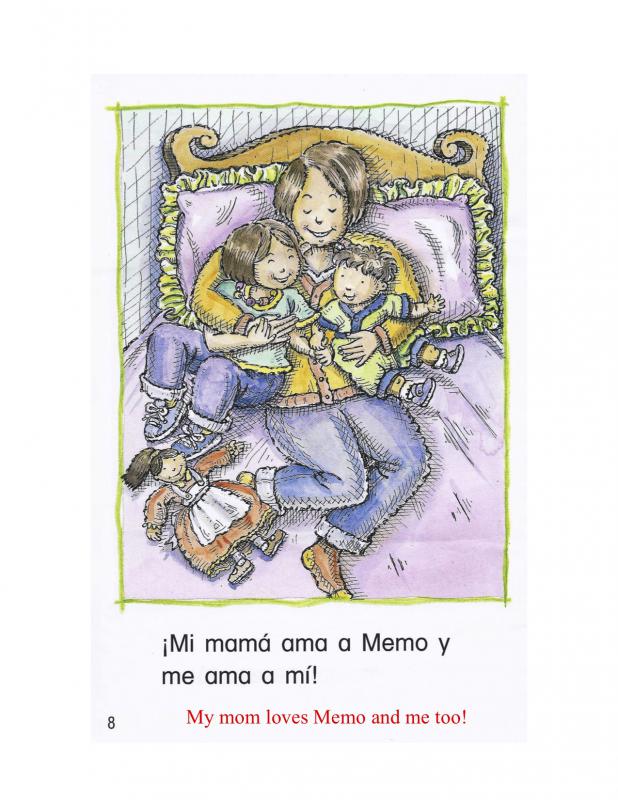

Mi mamá, Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) and Persepolis can attest to Mc. Cloud’s idea that realistic depictions do not allow to fully take in the feeling of what the plot is. On the other hand, cartoons help us readers make a connection with the image of the character on the page with the image of the character we have in our minds and we give authority to the image we see on the page. In Mi mamá, Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) the child can see a reflection of how a kid looks and acts given a particular situation. In Persepolis the cartoon of the young girl immediately reflects who Marjane Satrapi is, it says so on the first panel of the first page of the first book as shown below:

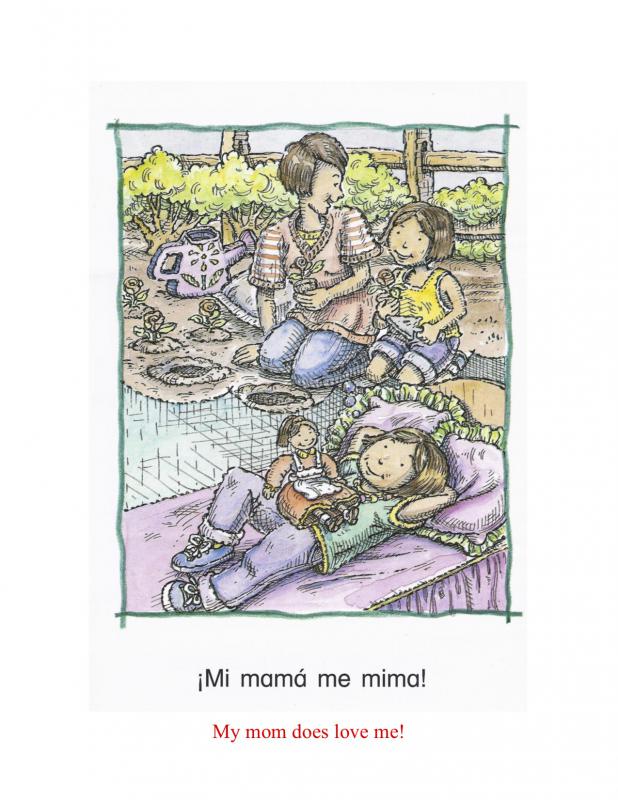

Relateability is essential for both the picture book and the graphic novel but in the case of children’s books it goes hand in hand with empathy. Picture books can provide the children with the feeling that it is fine to vicariously express certain feelings that come with the situation at hand and later finding a solution for them.

Since children’s books and graphic novels share many similarities, we can read children’s books as if they were a graphic novel and put our visual, textual and analytical literacies to the test. For this exercise I will use Memo y yo (My Mom, Memo and I) because of the quality of the illustrations; they are more colorful and have more details. These illustrations have lots of details, are colorful and are large enough for the child to read the image on its own and find the story within the initial illustration. It is common knowledge that children’s books have a simple storyline, which translates into very few illustrations and very few pages. Mi mamá, Memo y yo has only eight pages in which six of them are have their respective line of text at the bottom.

If this short story was read as a graphic novel each illustration is equivalent to a panel. The best way to read it as if it were a graphic novel would be from left to right (not from top to bottom, if it had multiple panels and then proceed to the following page) and keep in mind the “gutter” that bisects the pages. As mentioned before, “gutters” give our minds a time span (you choose how big or small you want it to be) to imagine or anticipate what will come next in the upcoming panel. The reader can use the “gutter” to ask the child questions or have the child ask him/her questions.

Both graphic novels and children books can belong to the same genre regardless of their length, Persepolis and Mi mamá, Memo y yo narrate someone’s life story, they share the structure of having a picture complement text and tell a story that way. The only new aspect that currently differentiates children’s books and graphic novels is the importance and dedication in which the scholarly community is studying the graphic novel. Even though scholars consider them an emerging genre, we have always been exposed to graphic novels; we just refer to them with a different name based on the time in our lives we read them. The stages that must be followed with the act of reading (the way a text is read and interpreted might) will remain the same.

Works Cited:

Foster, Thomas. How to Read Literature Like a Professor. 1st. New York,London,Toronto,Sydney: Harper and Row Publishers, 2003. Print.

Galda, Lee. "Children's Books: Visual Literacy: Exploring Art and Illustration in Children's Books." Web. 5 May 2012. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20201117