Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Wisdom, Serenity and Free Will Revisited

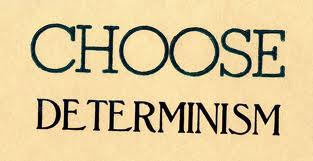

Is life a series of choices or is it predetermined? How each of us addresses this question is key to our understanding of life, our purpose and our happiness. If you feel that you have free will, you feel agency and an ability to impact the behavior of yourself and others and to choose a direction for the events in your life. But is it a binary, are the two possibilities complete free will or complete determinism? In this paper I would like to investigate how they work together. I think that many of us believe that we have free will but then make choices based on determinism. Why do we behave in this way, how can we change it and what would the impact be?

In the Spring of 2012, I was sitting in my Literary Kinds English class, engaged in a discussion of Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-5 when a related debate broke out. How much free will does each of us have in making our life choices? A prime question involved how much free will we give ourselves to make choices. Some say that they HAD to go to college, for example, they can’t imagine what would happen in their lives, in their relationships with their family and friends if they hadn’t. Given those consequences, the only “choice” was to go to college, there was no free will to make a different decision. Others argued that even though choice of not going to college couldn’t be considered, it still counts as a choice and free will is still in tact.

So how can we have free will but not choose to use it…not even consider all of the possibilities? In The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail, Jonathan Haidt makes the argument that many of our decisions are determined by our cultural and social upbringing and that once those influences are in place, we economize our energy by never rethinking the consequences of those accepted choices. In certain defined situations, we always make the same choice without thinking, and we refer to that choice as our gut instinct. We rely on it and fall back on it. For example, in looking at the causality of reasoning, Haidt, Koller and Dias (1993) [1] (Emotional Dog p. 817) asked Americans and Brazilians to react to actions that were offensive, but harmless. The stories indicated that there was no plausible harm done and no one was hurt. These stories included such scenarios as eating one’s dead pet dog. Despite the lack of harmful consequences, respondents found the actions to be universally wrong. They went with their gut instinct despite their lack of ability to reason it out. Haidt and Hersh (Haidt et al., 2000) in questioning conservatives and liberals on sexual morality issues

… also found that participants were often ‘morally dumbfounded;’ that is, they would stutter, laugh and express surprise at their inability to find supporting reasons, yet they would not change their initial judgments of condemnation. [2](Emotional Dog p. 817)

Haidt makes the argument that we are socialized to have certain “gut” instincts. The social intuitionist model of reasoning proposes that moral judgment is driven by intuitions and then reasoned ex post facto. So how do these intuitions form? Haidt molds several experimental findings to determine that it is through maturation and participation in a specific cultural environment:

… it is primarily through participation in custom complexes (Shweder et all., 1998) involving sensory, motor and other forms of implicit knowledge (Fiske, 1999; Lieberman, 2000; Shore 1996) shared with one’s peers during the sensitive period of late childhood and adolescence (Harris, 1995; Huttenlocher, 1994; Minoura, 1992) that one comes to feel, physically and emotionally (Damasio, 1994; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999), the self-evident truth of moral propositions.[3] (Emotional Dog p. 828)

These findings show that there are sensitive periods during childhood when we are primed to learn from and imitate those in our culture and to engage in activities in such a way as to feel benefits from the physical and emotional environment that shape how we act and how we make our “innate” judgments and decisions later in life. All of these aspects are necessary and important to that molding of our instincts and are unique to our environment. He uses the example of children in Orissa, India who learn about purity at a young age. There is structure in the temple in terms of only allowing those who have properly bathed into the central courtyard, and additional structures at home and with the body. There are levels and rules that govern different zones of purity. Children learn customs such as when to remove their shoes and when to show deference, which then primes them, later in life, to accept the ideas that are in concert with what they have learned, imitated and experienced so “their truth feels self-evident (Lakoff, 1987).” [4] (Emotional Dog p.827) He contrasts this with American children who are immersed in a different culture. As a result, when an American adult travels to Orissa, he can learn the rules,

…but he knows these things only in a shallow, factual, consciously accessible way; he does not know these things in a deep cognitive, affective, motoric way that a properly enculturated Oriya knows them. [5] (Emotional Dog p.827-828]

In addition to our cultural indoctrinations producing a quick form of non-conscious decision making, there is also the expense that we pay when we expend energy to consciously make decisions and, as a result, we tend to try to find ways to economize. In The Paradox of Choice, [6] Barry Schwartz discusses the overwhelming number of choices we’re presented with on a day-to-day, moment-to-moment basis. Even when you go to the grocery store just to buy mustard, you have so many options to take into consideration that it becomes mentally tiring and so time-consuming that it detracts from the other aspects of our lives that are more enjoyable and rewarding. If you take the time to thoroughly reason through every possibility available to you, you would not have time for anything else.

Therefore, it is sometimes necessary to have a quick way to make a determination. We need to use what Schwartz refers to as “Second Order” decisions. For example, the decision to follow a rule. When you have a rule, you don’t think about how to make the decision, you just follow the rule. Presumptions are another form of second order decisions. They involve setting a default decision and sticking with it, for example the size font that you use on the computer. A third form of second order decision is a standard. Options are divided into two categories based on whether they meet the standard. This makes the reasoning less involved because all you are evaluating is whether something meets the standard.

But how do we determine which decisions should be made using “Second Order” strategies and which should be fully reasoned? In The Paradox of Choice, Schwartz argues that we need to first decide on what the important decision are. How much does this decision really matter in our lives? This is the crucial step in determining whether a decision can be made in a “Second Order” fashion or whether it should be fully reasoned. Despite the importance of this step, I would argue that it’s not always considered. As described in The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail, I think that our indoctrinations don’t always allow us to take a step back and figure out what is important. Our instincts are used as presumptions and are left alone.

So with all of this determinism that develops throughout our lives that may not even be considered on a conscious level, how do we break out of these molds? What can we do to affect a change when it really matters?

In Daniel Dennett’s Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, Dennett argues that what makes humans so unique is our ability to imagine possibilities and play them out in our heads to determine the best choice. “…as Sir Karl Popper once elegantly put it, this design enhancement ‘permits our hypothesis to die in our stead.’” [7] (Dangerous Idea p. 375) Different scenarios can be performed in an inner environment (our heads) and the optimal outcome can then be enacted. Dennett quotes Holland, (1992 p. 25)

An internal model allows a system to look ahead to the future consequences of current actions, without actually committing itself to those actions. In particular, the system can avoid acts that would set it irretrievable down some road to future disaster. [8] (Dangerous Idea p.379)

Dennett goes on to say that there is a way to take this advantage a step farther. The “Gregorian” creature “imports mind tools from the (cultural) environment.” [9] (Dangerous Idea p. 378) This provides an inner environment with an expanded canvas to explore additional possibilities and outcomes.

When we read fiction, we are often challenged about why we believe the things that we do. In a satire, for example, our default reasoning is questioned. Might fiction be the tool of the “Gregorian” creature?... A way to bring the assumptions of our cultural indoctrinations and the subjects of our “Second Order” decisions into the realm of consciousness? Might it help us to explore why we make the decisions that we do and to break out of our indoctrinated molds?

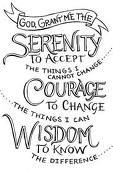

I think that Slaughterhouse-5 is just this type of tool. Vonnegut presents us with a new environment to explore the boundaries of free will, the consequences of believing in determinism and a scenario that helps us to reimagine how we make our own decisions. Vonnegut’s novel introduces us to Billy Pilgrim, a man who was subject to all of war’s physical destruction and mental hollowing. Throughout the story, Pilgrim wonders through in acceptance of all of the situations that are presented to him. He readily allows himself to be kidnapped by Aliens, he accepts when he will die and he accepts that he is in war. Despite the main character’s acquiescence, Vonnegut displays the Serenity prayer in the novel, a mantra of free will:

God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom always to tell the difference.

Does Billy have the ability to follow this advice? The Trafalmadorians only follow the first phrase, acceptance, but Earthlings believe that we have the agency in all of these phrases. Is Vonnegut suggesting that Billy does have free will and that we can choose not to have war?

To explore this theme, I’d like to look at the contrast between the Trafalmadorian view of agency versus the Earthling view. The Trafalmadorians believe that the idea of free will is exclusive to those on Earth:

"If I hadn’t spent so much time studying Earthlings,” said the Trafalmadorian, “I wouldn’t have any idea what was meant be ‘free will…’ only on Earth is there any talk of free will.” [10]

They believe that, “All time is all time… it does not lend itself to warnings or expectations.” [11] As a result of this view, there is no agency for change, everything that is supposed to happen will happen, you cannot choose to go in a different direction, you must accept what happens because that is what is supposed to happen. The Trafalmadorians can only practice acceptance, not change.

By contrast, those on Earth think that there is free will. According to the Trafalmadorian,

“Earthlings are great explainers, explaining why this event is structured as it is, telling how other events may be achieved or avoided.” [12]

Further, at the beginning of his war experience, Billy would always tell his fellow soldiers, “’You guys go on without me,’ he said again and again.” [13] But he was always pushed on and they would never leave him alone or let him quit as he desired. In the beginning, we see that Billy was making an attempt at agency, he believed it was possible, but the war was too big for him to change, so he had to go along and accept it.

Given the contrasting views of agency for Earthlings versus Trafalmadorians, what can be gleaned, is it better to just accept that war is our “fate” or do we have free will to change that?

When Billy starts to accept the Trafalmadorian point of view, as seen by the fact that he doesn’t ever try to escape from the Alien Zoo or to alter the outcome of the events surrounding his death or try to prevent himself from being taken by the Aliens in the first place, his life becomes locked in. Whether or not he has any free will is of no consequence, he just accepts everything that comes to him. He learned this in war when he tried to express free will to quit, but it was not possible, so instead he’s learned to accept all that comes to him. This is the heart of the Trafalmadorian outlook, where they have wars but dismiss their consequences because that’s just the way that it goes. Their serenity is, “to accept the things I cannot change.” But putting this in conversation with free will, what could be different if we have the courage to change?

Currently, both points of view can result in war, but what if war was not glorified in movies and TV and Billy’s fellow soldiers didn’t drag him along in the war, what if war was not thought of as something to just accept? If you have the courage to make a change and enough people have that view or can be convinced of that view, then war would not be inevitable, it would be unacceptable. What it means to have a free will is to believe that you have a free will, otherwise you’re just subject to “the way things are supposed to be” and the bad things can never change. The Trafalmadorians will always have war. There is a well-known quote by Edmund Burke:

All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.

If you don’t believe that you can do anything then how can you do anything?

In looking at the final phrase of the Serenity prayer, “the wisdom always to tell the difference,” wisdom is developed through experience. Billy experienced a lack of free will in the war so his view of his ability to make a difference is skewed in favor of acceptance rather than change. But what happens to Billy’s outlook if he was able to have the experience of free will? Might his wisdom be that you can change war if you don’t glorify it and go along with it?

The novel makes me wonder about all of the ways that I don’t express what I believe to be my free will. When we had the discussion in our Literary Kinds class, about whether or not we HAD to go to college, so many of us accepted the decision to go using our cultural backdrop and very undeveloped reasoning along the lines of “my family would disown me if I didn’t” or “all smart people go to college after High School and I consider myself smart so I must go to college.” This leads to “Second Order” reasoning and a mere acceptance and non-consideration of so many decisions in life.

One of Schwartz’s central reasons for writing The Paradox of Choice was to explore the role of decision-making in happiness. While fully reasoning every decision will be too time-consuming to allow us to be the social beings that we need to be in order to be happy, we really need to consider how our decisions affect our happiness and be able to carefully select the decisions that we should reason through. The story of Billy Pilgrim and others like him help us to explore the role of our decision-making in our happiness and to explore how we decide which “choices” should be reasoned through. Fiction has the power to be the true friend and tool of the sophisticated “Gregorian” creature!

Bibliography and Works Cited

[1] Haidt, Jonathan. The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail. Psychological Review. 2001. Vol 108, No. 4 (p. 817)

[2] Haidt, Jonathan. The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail. Psychological Review. 2001. Vol 108, No. 4 (p. 817)

[3] Haidt, Jonathan. The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail. Psychological Review. 2001. Vol 108, No. 4 (p. 828)

[4] Haidt, Jonathan. The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail. Psychological Review. 2001. Vol 108, No. 4 (p. 827)

[5] Haidt, Jonathan. The Emotional Dog and His Rational Tail. Psychological Review. 2001. Vol 108, No. 4 (p. 827-828)

[ 6] Schwartz, Barry The Paradox of Choice: Why More is Less. Harper- Collins E-Books. 2004. Kindle Edition.

[7] Dennett, Daniel G., Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. Simon & Shuster Paperbacks, (1995). (p.375)

[8] Dennett, Daniel G., Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. Simon & Shuster Paperbacks, (1995). (p.379)

[9] Dennett, Daniel G., Darwin’s Dangerous Idea. Simon & Shuster Paperbacks, (1995). (p.378)

[10] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (location 1020-23)

[11] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (loc. 1015-20)

[12] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (loc 1015-20)

[13] Vonnegut, Kurt. Slaughterhouse-5. RosettaBooks LLC, New York. Kindle Edition (loc 418-22)

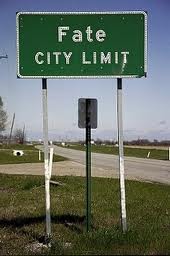

Pic Fate - [Google images: Determinism - William Lane Craig]