Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Defining Linguistics

In our class discussions this semester, we strove toward a definition of literary theory, and what the courses in that field of study were trying to accomplish. We described literature classes as having a set structure – they begin by tracing, or defining, the outlines of the genre they will be studying. Then they pick examples of the genre, and dissect them to see how well they fit within this definition, or where the specific examples go beyond the defined boundaries. But, as we pointed out on the first day of class, when placing ourselves into categories, not everyone in the room was an English major, or had taken many literary theory courses before. So, how do other classes within our school’s system work? Do other subjects have similar teaching styles to that used in literary theory? What is different about the structure used in other departments?

To answer this question, one would need to have taken a number of classes in one specific department within the college. As linguistics is a field in which I have taken a number of courses both here and at Haverford, I will strive to come up with answers to these questions in regards to linguistics.

The modern field of linguistics has its origins in the study of Greek and Sanskrit grammar performed by European linguists in the 18th century. This study eventually developed into the field of historical linguistics, a branch of linguistics which concentrates on describing and accounting for changes in languages over large periods of time, as well as studying the history of specific words or of whole speech communities.

Then some linguists noted that there were similarities between Persian and Sanskrit languages and Greek, Latin and Celtic ones. From this idea, historical linguistics branched into comparative linguistics, a field mainly concerned with comparing languages and establishing any relations they may have. For example, Spanish and Italian are both romance languages; that is a relationship. Japanese is not related to any romance languages, however, but the languages share some words in common. The Japanese word for bread, “pan,” is the same as the Spanish one, and very similar to the Italian one, “pane.” Why, if the languages are not related? Perhaps because Marco Polo and other sailors of his time, who were mainly speakers of one romance language or another, were the first to widely introduce bread into the Japanese culture, prompting the Japanese to adopt their name for it. The field of comparative linguistics is comparable to literary theory, insofar as it has to do with comparing and contrasting specific examples (languages in this case) within a genre (language families in this case) and seeing where and how they exceed the generic limits (what makes one Romance language different from another; what influences caused this, etc).

Ferdinand de Saussure, on the other hand, proposed a different way of considering the study of language – he looked at it as a formal system composed of distinct elements which could be separated and studied on their own, in order to better understand the whole. His ideas eventually helped to form the basis of descriptive linguistics. Descriptive linguists seek to analyze and describe the structure of a language with regard to how it is spoken. The aim is to describe the language as it is used in the world, not as it should be used according to prescriptive grammar.

From the descriptive theory come the four main subdivisions of the field that are taught in schools today (historical linguistics classes aside): phonetics, phonology, syntax and semantics. Phonetics studies the physical properties of speech (how sounds are produced by the mouth, the properties of the sound waves emitted during speech, etc). Phonology studies the sound system (stress, accent, tone, etc) and the way those sounds function within a language. Syntax studies the generalized rules, or the underlying grammar, of a language (what the rules are that generate all of the possible utterances of speech in a given language). Semantics studies the meaning of words and phrases, as well as the different interpretations that can be given to a specific utterance (for example, “I want a cat” could mean that I want a specific cat which I have already picked out at the pet store, or it could mean that in general, I would like to acquire a cat, but do not have a specific feline in mind). Here in the Tri-Co (since most of the classes are either at Swarthmore or run on Bryn Mawr or Haverford campuses by visiting professors from Swarthmore), these last four areas form the basis for most of the linguistics major programs (classes in historical linguistics and related fields are also offered, but since I’ll be speaking from personal experience and I haven’t taken any of those, I can’t comment on the way those classes are structured).

To start off with, of the courses I’ve taken, I think semantics is the area of linguistics that most relates to literary theory courses. A lot of the ideas in semantics come from Saussure’s ideas of the signifier, the signified and the referent (as in, the relationships between the idea being references, and the word or symbol used to refer to it), ideas which are reminiscent of Derrida’s theory of an idea as “reality,” spoken word as an interpretation of that reality, written word as an interpretation of that, and so forth. Semantics is not as concerned with the written word, as it is with the spoken word, and how interpretation affects comprehension in oral discourses (or, in the case of sign languages, gestured ones), whereas literary theory is obviously usually more concerned with the interpretation of written words, but still, the two disciplines seem to overlap in that area. Semantics courses tend to play with the boundaries of definition by examining all possible interpretations of specific words or phrases, and analyzing which interpretation speakers are likely to make based on the context of the word/phrase, and on the speaker’s knowledge of the language (for example, native speakers have an easier time understanding subtly distinct phrases than nonnative speakers do). In some ways, this could be likened to the manner in which literary theorists try to look at different interpretations of a text as a whole, but theorists usually tend to be arguing for one specific interpretation or manner of interpreting over another, whereas semanticists would just try to describe all of the different possible interpretations without issuing any value judgments.

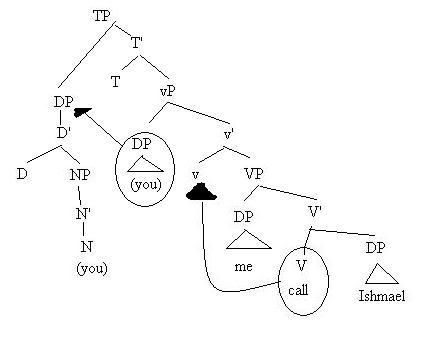

Syntax courses, on the other hand, probably more closely resemble math classes than classes on literature. A main goal in the field of syntax is to try to come up with a “universal grammar,” or, the underlying grammatical principles that govern all languages. The surface rules of all of the languages in the world can be vastly different, but syntax attempts to find generalized (and often less obvious) traits that can be considered common to them all. For this purpose, syntax generates and tests rules, with the object of finding commonalities that hold true for all languages. An example of one such rule would be the head rule. Two languages might appear to have nothing in common, because the sentence structure trees for a sentence in, say, English might look like the following:

Notice that the “heads” of each phrase (for instance, the head of the NP is the N, the head of the DP is the D) fall to the left in each portion of the tree. That is because English is a head-initial language. Whereas in a sentence structure for another language, say, most Oriental languages, the heads would fall to the right of the phrases (so, “a friend” would be written “friend a”). If one only looks at the surface grammar, the two languages are unrelated. However, if one takes a more general look at the rules behind it, a relationship can be found. The head rule indicates whether a language is head-initial or head-final with its utterances. The majority of the world’s languages (around 97%) can be categorized by using a series of rules such as the head rule in order to set the parameters for the languages. However, the rules are still being adjusted (as you can see even from the relatively simple tree above, syntax rules have come a long way from drawing sentence trees simply according to diagrams like:

S

NP VP

NP

which were commonly used in the earlier days of the field’s development. Of course, the noun and verb phrases still appear within the sentence structures, but other clauses have been added in order to allow for broader generalizations, and so that more of the world’s languages can be included.

Phonetics, the study of the physical properties of speech, is taught as more of a laboratory class than either a math or a literary course, on the other hand. Phonetics courses usually take place at least partially in a computer lab, working with equipment to analyze sound waves and speech patterns. Usually the speaker uses his/her own voice recordings to observe the various traits of speech and learn how to read pitch and intonation, though previously recorded files of other speakers can be used (especially if the specific trait being analyzed is better demonstrable in a language other than English – for example, tone is not a major factor in the English language, because placing influence on one syllable over another doesn’t usually differentiate words; however, in Thai, the same word pronounced with different tonal values can mean completely different things). Visual recordings of X-rays (previously taken, of course, since the modern world discovered the risks of using X-ray machines too often) also often feature in phonetics classes, in order to study the physical contractions and exercises the mouth needs to perform in order to produce speech (the movements of the tongue are among the fastest and most precise ones that human beings can make). The main goal of phonetics is to understand the process of speech, and again, to describe all of the varied physical properties associated with it.

Phonology might be best described as the union of phonetics and syntax. Phonology considers the physical properties of speech, again, but it categorizes these properties in order to understand how meaning is made. For example, the vowel [u] (pronounced like the vowel in “boo”) is a high back vowel, meaning it is pronounced in the back of the mouth with the tongue raised (or high). Phonology categorizes this vowel as [+back +high], and contrasts it with the [-back +high] vowel, which would be [i] (pronounced like the vowel in “street”), and is pronounced in the front of the mouth. Phonology uses these categories to mathematically define shifts in a language, hence its relation to syntax. For instance, phonological categories would be used to write a “mathematic” formula to explain why, in English, the plural ending is pronounced differently in different cases. In “cases,” it is pronounced [əz], whereas in “cats,” it is pronounced [s]. A simple set of rules explains that firstly, /-z/ à [s] / [-voice]__ (that is, the underlying “z” form of the plural in English is pronounced as an “s” after a voiceless consonant – that is, a consonant that is pronounced without vibration of the vocal cords, such as “t”), and secondly, ø à [ə] / [+sibilant]__[+sibilant] (that is, if a plural comes after a sibilant sound – any sound of the “s” or “z” variety, or some variation thereof – a schwa vowel, which is usually pronounced “eh” or “uh” is inserted). These two rules together explain why the word “cases” is not pronounced “case-sss.” The main goal of phonology is similar to that of syntax, in that phonologists seek to find the principles that govern pronunciation throughout the world’s languages. However, phonology does not seek to generalize quite so much as syntax does, in that the phonological rules of a language are written to apply only to that language, although they are written with the same parameters used to write the rules for all languages. The same definition system, written using such specifiers as [+back] or [-voice], is used in all of the rules, but the rules themselves differ from language to language, unlike in syntax, where the field searches for one set of rules to use universally.

One element that carries across all of these sub-fields, though, is the descriptivism which formed the basis for these branches of linguistics. Grammar-school classes teach prescriptively, telling students what is and is not proper in language (do not use “they” to refer to a singular, gender-neutral person; do not say “ain’t”), whereas linguistics classes teach a descriptive view of language. In English, nowadays, one can make themselves perfectly understood by using “they” in order to refer to a singular, gender-neutral person (since the use of “he” in such positions, as it was done in the past, is discouraged now). “Ain’t” is a perfectly comprehensible word, and even the strictest prescriptive grammar teachers ain’t going to misunderstand the word if you use it in a sentence, they’re merely going to protest the use of it because “isn’t” is “proper.”

While college English courses are more focused on topics such as literary theory, and not so much on prescribed grammar, academic writing and literary essays still require that the prescribed grammar rules be followed by the authors. This is the first area of conflict that comes to mind when comparing and contrasting literature courses with linguistic ones. Many linguists would go so far as to say that academic writing is not an example of a natural use of the language, in fact, because the rules and regulations that accompany it are so prescribed. Others would say that it is one example of a use for language, but even they would probably agree that it is not the best example to study in order to discover the underlying grammatical rules and structure of said language, because the underlying rules are obscured by the prescribed ones enforced in such a usage.

On the other hand, literary theorists and linguists have similar tasks when it comes to analyzing within their fields. Theorists analyze a text (or texts, or a genre) to make an argument or claim about it, other theorists analyze that analysis and make a claim or argument disputing the first, and so on. Linguists go through the same revision processes – one linguist will write a paper about how sentence structures should be drawn using S as the heading, then another linguist writes a paper about how the heading should be TP, for tense phrase, because otherwise it’s difficult to explain how past, present or future tenses are brought into a sentence structure, then someone else writes a paper about how other phrases should come before the tense phrase, and so on. In the way that theorists propose methods of defining genres and analyzing specific examples within them, linguists propose methods of defining rule-sets and analyzing specific languages to see how those rules hold up.

A task of literary theorists when it comes to genres seems to be deciding which texts fall within which genres and why, or explaining why a text should still be considered a part of one genre, even if it violates or strains at the definition of that genre. Linguists come up against a similar challenge, when analyzing dialects of a language, or language hybrids (such as Spanglish), but they do not generally try to argue for the merits of one dialect over another or to place such examples into categories. Linguistics is descriptive, by and large, and categorizing a language, or calling one dialect a language and another merely a dialect, is prescriptive. In that way, the two fields differ, I think, because literary theory strives to make or break or dispute judgments, whereas linguistics strives to make as few judgments as possible about what is being studied.

That is not to say that value judgments are never made, they certainly are, but usually it is done when the speaker has an agenda to press. For example, constant disputes are being raised about whether regional dialects, such as the southern dialect or the northeastern one, are dialects of English or merely accents or, as some have argued, individual languages unto themselves. Many times judgments are made about people depending on what dialect or version of English they speak. The “standard” American accent is the Midwestern one, used on most public television and radio stations, which is why it is the accent most readily associated with a person who is “well off” or “successful.” Someone applying for a job who speaks the dialect used in the Bronx or New York City in general, on the other hand, may be judged less intelligent or successful for using that dialect.

Because language is so often related to politics and issues of regional pride or discrimination, most linguistics courses do remain as descriptive as possible in this regard. Accents will be discussed (technically, every single person speaks a different accent, because our accent is what makes our voice distinguishable from everyone else’s, but people raised in a closer proximity will tend to speak more similarly than a person raised in another area or with a different group of speakers), dialects will be covered (dialects are groupings of these speakers raised in close proximity or with the same influences, who have developed relatively similar accents in their pronunciation), and language boundaries will be touched-upon (for example, the differences between British and American English will be discussed – are they separate languages? They are mutually intelligible, yet Swedish and Icelandic are mutually intelligible, yet are classified as separate languages, not dialects). But papers arguing one way or another definitively on such topics are rarer in linguistics than in literary theory, probably because if you argued that Moby Dick was not a novel, unless Herman Melville returned from the grave, no one would be personally offended at this declaration, even if they disagreed with it strongly. However, if you were to argue that Catalan is not a language, merely a dialect of Spanish, you would probably offend a great deal of Catalan-speakers who tie their identity as Catalonians to their use of the Catalan language rather than the Spanish (Castilian) one.

Linguistics courses teach students to look very carefully at all sides of an issue and to analyze situations by breaking them down systematically and looking at the parts to help better understand the whole. However, linguistics also tends to avoid making arguments and discussions which could provoke interesting disputes. The debates over dialects versus languages and the divides therein are being discussed in other fields already, such as specific language fields (for example, in Spanish departments, the different regional languages of Spain are discussed, and whether or not they should be considered separate languages is debated). The majority of linguistics courses are avoiding the subject, though, when the in-depth analyses performed in those fields could add new topics to the discussions.

Some courses which aren’t officially linguistics courses, but which are closely related, do touch on the subject, which may mean that discussions will eventually open up within the specific fields of linguistics. For instance, politics of language and philosophy of language courses both touch on the topic of language and/or dialect as identity, as well as how languages can be used as tools of political power, while oppressing other minority languages. Spanish courses discuss the linguistic situation in the Spanish-speaking world, with relation to the many different varieties of the language, and how the varieties are looked upon by the Academy of Spanish. Some French courses (I have heard, though I have not taken one myself) touch on the subject of the Academy of French, too, and raised discussion about whether it is “preserving the French language,” or causing even more bias again those who speak an “un-prescribed” dialect of French. The discussions are happening, just perhaps not in all of the classrooms where they should be.

Saying so, of course, might be cross-listing linguistics with literary theory a little too closely. On the other hand, my major is something of a hybrid of the two, so I wouldn’t say such crossings are necessarily a bad thing.

Comments

putting linguistics into play with politics

Thanks for the thoughtful overview of your field, Ellen; there's much here of interest/instruction for me. Three moments stay with me: