Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Redesigning Setting the Scene: Reading for Minaj Feminism

For my final project, I would like to focus on our pop culture discussions in the beginning of each class session, or “Setting the Scene.” Our assignments to bring in a pop culture item, usually a music video or a post from the blogging website, Tumblr, as a potential lead in to our intended academic texts and their subsequent dialogues (particularly the ones revolving around music videos) often were cut short—much too short for a satisfying analytic reading of the often multi-faceted material we were presented with. Some classmates suggested we process topics of our discussions prior to class meeting to allow for a more comprehensive reading. However, my qualm did not arise from ability of lack thereof to process what I was seeing, it was the way in which most discussions ended, an ending reminiscent of our “Is this a feminist text?” conundrum: an ending that reached for the shallow aim of finding our own preset definitions of feminism within these three to four minute worlds. I was most disappointed by the feminisms we didn’t see, even flat out ignored, in certain “setting the scene” presentations. Of our discussion of non-conventional feminist music figures my interest was most peaked by our rather curt reading of Nicki Minaj’s video, “Stupid Hoe.” Her overtly sexual and aggressive music video presentation was quickly judged as trite and not worth the time of the class to watch the entirety of. It was surprising, to say the least, to observe the class who, earlier in the semester, completely rejected the notion of categorizing materials as feminist or nonfemininst, decided this woman, and her possible scope of feminism was to be deemed illegitimate. I was, and still continue to be, puzzled by the seemingly unanimous response to this popular culture representative. Thinking about the validity of our class’ response, I began to wrestle with the questions, “What does it mean that we do not see feminism in our own popular culture? “ and “What then, is the justification for its presence and its mass consumption? Is there really no Minaj feminism?”

It would seem obvious by judging Nicki Minaj’s music video, “Stupid Hoe,” that she does not affiliate herself with an image of a pop star that sets to uplift other women in a markedly feminist way. Admittedly, it may be difficult to see value her highly provocative, outlandish costumes that extenuate her sexuality for the feminist that has been fighting against the public objectification of the “video vixen.” But Nicki Minaj is a highly active participant in the creation of her career, exhibiting a powerful handle on the production of her music video and embodies the defamed image of the video vixen, and within that persona, ushers herself to the forefront of the video’s narrative.

Tackling the issue of our less than successful “Setting the Scene” discussion, I will attempt to do a close reading of the video we saw in class, “Stupid Hoe” in hopes of giving a improved chance of the segment within this course to reach its full potential of realizing there is indeed a palpable manifestation of feminism in our popular culture .

The video opens with Nicki contorted in a statuesque pose as if she if exhibiting herself for the viewer’s voyeuristic consumption. She stands on a pedestal, taking her self-objectification beyond the circus exhibit level to the realm of a inanimacy; she is a trophy.

The video opens with Nicki contorted in a statuesque pose as if she if exhibiting herself for the viewer’s voyeuristic consumption. She stands on a pedestal, taking her self-objectification beyond the circus exhibit level to the realm of a inanimacy; she is a trophy.

Next, and quite prevalently throughout the progression of the video appear the high-speed flashes of two alternating images:

Minaj’s buttocks and the intimidating scowl of her threatening alter-ego, Roman Zolanski. The juxtaposition of these two images provide a stark contrast between the sexually inviting scantily clad gyrating headless female figure and the jarring visage of a reprimanding, angry extremely vocal disembodied woman’s head. Minaj has admitted that her “Roman” side comes to light when she feels someone needs to be harshly reprimanded or put in their proper place. So, what is our offense as viewers? Looking to the image entangled with Roman’s appearance, it would seemed that by simply looking at exclusively at her sexualized body and ignoring the rest of her presence, her creative, artistic agency, we are misstepping as consumers of her persona as an entertainer. Minaj realizes herself as a sexual figure and lets the viewer take pleasure in that fact, but at the same time does not let this pleasure go without the intervention of her commanding rap star presence represented as the impressive force in the character of a defensive Roman. Roman’s costuming directly demonstrates this message:

Roman wears a revealing leotard, heels, and garters but those suggestive items are not without a closed corset hood and a gun holster on her thigh.

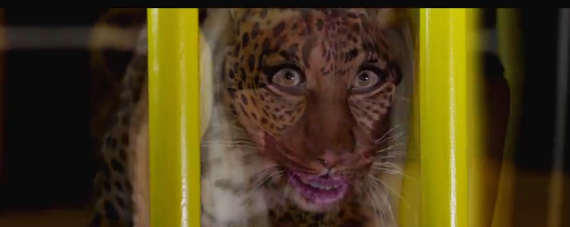

In the next segment of the video, Nicki addresses the dehumanizing aspect of her perceived image in the animalizing sphere. She appears with her hair pulled back to reveal her small, cat-like ears accompanied with cat eye makeup and the dotting of whiskers on her cheeks.

Once again, the slight allusion is taken to an more obvious and arresting level of imagery when Minaj presents herself as a caged sexualized figure in a cat suit. She literally transforms into a leopard— an animal thought biblically to represent lustfulness and sin—soon after finding herself in the cage. This is to suggest that the overwhelming voyeurism, in this case the viewer watching Nicki through glaring yellow bars, is such to reduce her presence that of an exoticized, lustful animal that is voiceless and must be consumed visually solely.

In the third segment of the video, Minaj infantilizes herself and dissolves into yet another the alter-ego. Standing on a large pink chair in a doll’s costume, it is clear by Nicki’s heightened, singsong pitch that she is assuming a child’s position. Even from this belittled standpoint she is understood as an extension of the Zolanski family and its confrontational disposition. As an aid to her disadvantage short stature, just in the way women as disadvantaged in the rap industry, she stands on the power of a chair to continue the attacking narrative.

Considering the themes and images at work in this music video, one is left to grapple with the elephant in the proverbial room: Why this particular song for this particular music video narrative?

The bizarre sideshow motif is reminiscent of what Sara Baartman, the original figure of African descent to be subject to vixenhood voyeurism, experienced. Beginning with the abduction and career of Baartman as a sexual sideshow freak to be paraded around “civilized” circles, the video vixen has long stemming roots. Minaj, by exhibiting herself in the “Stupid Hoe” video, snatches an abducted sexual agency back from a tradition of viewers who have made inanimate, infantilized, and animalized the viewed. The “Stupid Hoe” maintains the sentiment of snatching agency by turning the viewer’s judgments back on the viewer and condescending to them.

Does this make Minaj a feminist? If her goal seems to be role reversal, is she a power feminist?

By close reading her interactions with men in which she features in music videos, one may be able to get closer to those answers. In fellow rapper Ludacris’ music video for the song “My Chick Bad” he paints a bare bones theme with the single creative assumption that he plays a director’s role in relation to the women he associates with; to put it simply, Ludacris is calling the shots. By his direction, the women in the video are merely silhouettes, providing an avenue for removed voyeurism. According to this “My Chick” could be absolutely anyone. Soon after this dynamic has been set up, Minaj interrupts this narrative of possessive braggery. Comparable to her intervention in the “Stupid Hoe” video, Nicki Minaj takes a clearly sexual narrative in which the woman is, for the most part, a passive participant and inserts an active, fierce character. Her she appears as Roman once again, but this time she assumes the role of a source of horror. She wrestles madly in a constrictive chair in a makeshift straight jacket as she raps:

By close reading her interactions with men in which she features in music videos, one may be able to get closer to those answers. In fellow rapper Ludacris’ music video for the song “My Chick Bad” he paints a bare bones theme with the single creative assumption that he plays a director’s role in relation to the women he associates with; to put it simply, Ludacris is calling the shots. By his direction, the women in the video are merely silhouettes, providing an avenue for removed voyeurism. According to this “My Chick” could be absolutely anyone. Soon after this dynamic has been set up, Minaj interrupts this narrative of possessive braggery. Comparable to her intervention in the “Stupid Hoe” video, Nicki Minaj takes a clearly sexual narrative in which the woman is, for the most part, a passive participant and inserts an active, fierce character. Her she appears as Roman once again, but this time she assumes the role of a source of horror. She wrestles madly in a constrictive chair in a makeshift straight jacket as she raps:

“It-it-it-it-it's goin' down, basement

Friday the 13th, guess who's playin' Jason

Tuck yourself in, you better hold onto your teddy

It's Nightmare on Elm Street and guess who's playin' Freddy

My chick bad, chef cookin' for me

They say my shoe game crazy, the mental asylum lookin for me”

By her allusions to horror films such as Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th, she places herself within a category of nightmarish characters— characters who aim to jar their victims from their otherwise placid lifestyles. While the world of women within the rap industry is quite a ways from placid, Minaj still confronts that women are possessions, not independent entities of their own reputable consequence. Minaj, by literally presenting herself as restrained, she brings the plight of the video vixen of being praised, as they as in Ludacris’ song and many other male rappers, but only as long they are possessions, or “My Chick.” Minaj has a growing repertoire of making this feature intervention in most of her guest rap verses and video performances. In Big Sean’s Dance (A$$) music video, Minaj combats Big Sean’s directive lyrics and turns the gaze back on him:

B-B-Big Sean, b-boy, how big is you?

Gimme all yo’ money and gimme all yo’ residuals

Then slap it on my ass, ass, ass…

Here she makes it clear that as men in the music industry like Big Sean may see her and other vixens to be used as a means to an end (i.e. : sex), she too has motives of her. Actively placing herself within the role of a sexual temptress or “bad bitch,” Minaj makes the intervention that women too, are interested in optimum sexual prowess and can take power or “money” Minaj makes the intervention that women too, are interested in optimum sexual prowess and can take power or “money” and “residuals” from men with the tool of her sexuality. Her “ass” or sexuality is her power and she is in control. She visually demonstrates this sentiment by her interactions with Big Sean. She participates in the trend throughout the video of rump shaking but remains impossible for Big Sean to get a full grasp or handle on. Minaj barely touches Sean in most of their shared screen time, only allowing him to loosely hold her hand for any extended period during the video. It is apparent he is incapable of controlling of her sexuality as his verses claim (“I’m looking all good I’m making her wet/ They pay me respect they pay me in checks/ And if she look good she pay me in sex/ Bounce that ass (ass) it’s the roundest.”) She repeats this showing in her music video, “Beez In The Trap,” as she flaunts her body to the viewer but refuses to share or give up her powerful handle on her sex, poised and exerting absolute fierceness when put in interaction with guest rapper, 2Chainz.

In this video once again, she exhibits bondage imagery as she does in “My Chick Bad” and “Stupid Hoe.” She appears at the very beginning of the video behind a garble of barbed wire. As the video progresses however, the binded Nicki fades and is replaced by images of a the stoic Nicki Minaj in dialogue with other rappers in a club setting. She seats herself with both the male rappers and the video vixens and exhibits her control by not solely presenting herself as sexually appealing, but maintaining a position of power and authority as she holds wads of money while she raps.

When she is not in conflict with any male rap influence in shared rap roles she inhibits, Nicki moves into a progressive mode. In her music video for her song with Rihanna, “Fly,” she takes on a similar philosophy to that of Bell Hooks in the respect of revolutionary feminism. As opposed to the reformist feminism, which has the ultimate goal of reversing the roles of men and women, she seems to support in her rap embattlements with male rappers in aforementioned song performances, Minaj, in this video, brings out her endorsement of a revolutionary feminist cause. Using the powerful lyrics:

Everybody wanna' try to box me in

Suffocatin' everytime it locks me in

Paintin' their own pictures then they crop me in

But I will remain where the top begins

Caus' I am not a word, I am not a line

I am not a girl that could ever be defined

I am not fly I am levitation I represent an entire generation

it is clear that Minaj realizes and wants to break free from stereotypes placed upon her and other women of her “entire generation.” In this video performance the set is literally in ruins, with Minaj and Rihanna being the only ones present. Considering the interaction of the lyrics and the images in the video, both suggest that in order for the intent of Minaj’s lyrics to be manifested, something, the current rap industry must be destroyed or revolutionized.

By taking an in-depth look at Nicki Minaj’s entire music video exposure instead of one sampling followed by a 5 minute conversation, an entire world of her feminisms are uncovered. The issue with “Setting the Scene” is that music videos are often as independently pregnant with imagery and significance as much as the more scholarly texts we surrounded ourselves with during the semester. Music video analysis is an uprising form of literature that should be respected as such, and not lumped together as to miss its wonderful intricacies.

Works Cited

"Dance (A$$) Remix"- Big Sean Feat. Nicki Minaj

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pn1VGytzXus

"Beez In The Trap"- Nicki Minaj

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EmZvOhHF85I

"My Chick Bad" - Ludacris Feat. Nicki Minaj

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JqHliQijgvA&ob=av2e

"Stupid Hoe"- Nicki Minaj

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T6j4f8cHBIM&ob=av2e

Fly- Nicki Minaj Feat. Rihanna

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3n71KUiWn1I&feature=relmfu