Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Americanitis: The Trappings of Modernity

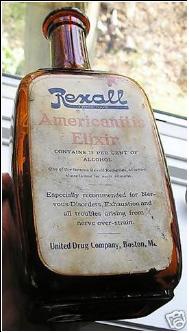

In reaction to the overwhelming response to neurasthenia, many apothecaries, drug stores, pharmacies, entrepreneurs, and medical practitioners chose to capitalize on the unique opportunity by developing potions and elixirs marketed to cure individuals of their nervous disorders. An array of products became available to the American public advertising their ability to relieve neurasthenia including the popular “Neurosine” that contained  cannabis and worked to lessen migraines and agitation while “hop bitters” were an alcohol-containing tonic geared towards men who were seeking a relief from their stressful, energy depleting duties. The “Americanitis Elixir,” “Dr. Miles’s Nervine,” and “Wheller’s Nerve Vitalizers” were also popular remedies and were heavily advertised in periodicals and newspapers. Neurologist S. Weir Mitchell who described Neurosthenia as a “disorder of capitalist modernity” developed the popular “rest cure” that was prescribed to the more serious cases of civilian Neurasthenia and encouraged sufferers to partake in bed rest, sponge baths, massage, and a diet of milk and eggs (11). Interestingly, the treatment of neurasthenia differed between men and women. The illness became increasingly gendered as women, when diagnosed, were instructed to cut themselves off intellectually. Charlotte Perkins Gilman was ordered by Mitchell to ‘never touch pen, brush, or pencil again’ and was confined to her bed. Males sufferers, such as Theodore Roosevelt, were treated much differently. Roosevelt, when diagnosed with asthmatic neurasthenia, was sent to a ranch in the Dakota Badlands. While Gilman found her experience to be the catalyst of a near mental breakdown, Roosevelt found his to be “physically restorative” and “life transforming” (12). While women were discouraged from any mental or physical pursuits, men were encouraged to reconnect with nature and the world around them.

cannabis and worked to lessen migraines and agitation while “hop bitters” were an alcohol-containing tonic geared towards men who were seeking a relief from their stressful, energy depleting duties. The “Americanitis Elixir,” “Dr. Miles’s Nervine,” and “Wheller’s Nerve Vitalizers” were also popular remedies and were heavily advertised in periodicals and newspapers. Neurologist S. Weir Mitchell who described Neurosthenia as a “disorder of capitalist modernity” developed the popular “rest cure” that was prescribed to the more serious cases of civilian Neurasthenia and encouraged sufferers to partake in bed rest, sponge baths, massage, and a diet of milk and eggs (11). Interestingly, the treatment of neurasthenia differed between men and women. The illness became increasingly gendered as women, when diagnosed, were instructed to cut themselves off intellectually. Charlotte Perkins Gilman was ordered by Mitchell to ‘never touch pen, brush, or pencil again’ and was confined to her bed. Males sufferers, such as Theodore Roosevelt, were treated much differently. Roosevelt, when diagnosed with asthmatic neurasthenia, was sent to a ranch in the Dakota Badlands. While Gilman found her experience to be the catalyst of a near mental breakdown, Roosevelt found his to be “physically restorative” and “life transforming” (12). While women were discouraged from any mental or physical pursuits, men were encouraged to reconnect with nature and the world around them.

The mass diagnosis and infatuation with “Americanitis” or neurasthenia in western psychiatry largely died down in the 1930s, but its essence is still ![]() alive today in the forms of similar illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome. Neurasthenia has a large place in today’s society as we are flooded with mental stimulation every moment of our lives in countless forms. College students and youth in general are especially prone to such mental stimulation as they are most informed on the latest technological and social progress rendering them the most susceptible to become entrenched in these new advancements. Previous “trappings of advancement” such as telegraphs and steam power that caused the depleted nerve energy of Americans

alive today in the forms of similar illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome. Neurasthenia has a large place in today’s society as we are flooded with mental stimulation every moment of our lives in countless forms. College students and youth in general are especially prone to such mental stimulation as they are most informed on the latest technological and social progress rendering them the most susceptible to become entrenched in these new advancements. Previous “trappings of advancement” such as telegraphs and steam power that caused the depleted nerve energy of Americans ![]() in the late eighteenth century pale in comparison to the technological trappings of today, including social networking sites, mp3 players, internet, smart phones, video games, television and an array of other technological accoutrements that serve useful purposes but stimulate the mind in ways that it has never experienced before. Video games, for example, are a complete bombardment of the senses as the player is saturated with rich images and booming sounds all the while harnessing their mental skills in order to navigate the game successfully. The stereotypical image of a “gamer” conjures images of laziness and lack of social interaction, if this stereotype is at all accurate it seems that the mental

in the late eighteenth century pale in comparison to the technological trappings of today, including social networking sites, mp3 players, internet, smart phones, video games, television and an array of other technological accoutrements that serve useful purposes but stimulate the mind in ways that it has never experienced before. Video games, for example, are a complete bombardment of the senses as the player is saturated with rich images and booming sounds all the while harnessing their mental skills in order to navigate the game successfully. The stereotypical image of a “gamer” conjures images of laziness and lack of social interaction, if this stereotype is at all accurate it seems that the mental ![]() saturation of video games can cause the depletion of nervous energies resulting in fatigue and inability to concentrate. Social networking sites are another example of modern “trappings of advancement” as they flood users with advertising, music, applications, and the ability to stay constantly connected to friends and family. It is easy to see how this all-encompassing form of communication and pop culture would be so appealing, but it also causes one to become addicted and detached from the outside world. Danielle Pope explains this 21st century addiction, “Frequent Facebook visits actually cause something psychologists refer to as

saturation of video games can cause the depletion of nervous energies resulting in fatigue and inability to concentrate. Social networking sites are another example of modern “trappings of advancement” as they flood users with advertising, music, applications, and the ability to stay constantly connected to friends and family. It is easy to see how this all-encompassing form of communication and pop culture would be so appealing, but it also causes one to become addicted and detached from the outside world. Danielle Pope explains this 21st century addiction, “Frequent Facebook visits actually cause something psychologists refer to as  intermittent reinforcement. Notifications, messages and invites reward you with an unpredictable high, much like gambling. That anticipation can get dangerously addictive” (Pope). Sites such as Facebook and MySpace not only put individuals at risk for neurasthenic symptoms, but the anticipation of connecting with peers can lead to an infatuation and obsession with checking for updates and messages. Although in the early eighteenth century this stimulation would be countered by potions and elixirs, the methods of today would include counseling and, in extreme cases, behavioral therapy. However, some potions and elixirs prescribed in the 18th century did contain substances such as cannabis and alcohol which remains a social problem of today. Many individuals in today’s fast pace society attempt to calm their nerves with the help of illegal substances and activities. It seems the only method that would successfully combat this mental bombardment would be a balancing act of sorts- an attempt to counter the mental stimulation with some kind of form of mental relaxation. If this balance is achieved, the depleted energies could recuperate and allow the individual to regain full mental capacity without the aid of substances or behavioral therapy.

intermittent reinforcement. Notifications, messages and invites reward you with an unpredictable high, much like gambling. That anticipation can get dangerously addictive” (Pope). Sites such as Facebook and MySpace not only put individuals at risk for neurasthenic symptoms, but the anticipation of connecting with peers can lead to an infatuation and obsession with checking for updates and messages. Although in the early eighteenth century this stimulation would be countered by potions and elixirs, the methods of today would include counseling and, in extreme cases, behavioral therapy. However, some potions and elixirs prescribed in the 18th century did contain substances such as cannabis and alcohol which remains a social problem of today. Many individuals in today’s fast pace society attempt to calm their nerves with the help of illegal substances and activities. It seems the only method that would successfully combat this mental bombardment would be a balancing act of sorts- an attempt to counter the mental stimulation with some kind of form of mental relaxation. If this balance is achieved, the depleted energies could recuperate and allow the individual to regain full mental capacity without the aid of substances or behavioral therapy.

Works Cited

Pope, Danielle. "Potential Facebook Addiction." Addiction Info. Interspire Webpublisher, 01/24/2008.

Web. 22 Apr 2010. <http://www.addictioninfo.org/articles/2171/1/Potential-Facebook-addiction/Page1.html>.

Comments

Pragmatism as a response to nervous exhaustion?

Marina--

I'm delighted, of course, that the work you are doing elsewhere on "cultural psychology" turned up the culturally specific diagnosis of "Americanitis," along with its diagnotistician and sufferer, our own William James. This is a great report both on the 19th century diagnosis and its contemporary trace, though I would like to know more about how you draw those latter connections (especially to chronic fatigue syndrome, for example, which from my understanding is seen now as post-viral, rather than as a reaction to overstimulation).

I have long been familiar with neurasthenia as part of the history of the treatment of women in this country, but had no idea that men were treated differently--"encouraged to reconnect with nature and the world around them," as you say, rather than, as women were, "discouraged from any mental or physical pursuits." That the disease was also class specific, understood as a “disorder of capitalist modernity” to which "the affluent and well-educated" were most susceptible, is also of great interest to me, and certainly expands my gender-specific understanding of both the disease and its treatment.

There are two ways in which I might imagine this project going on. One is to loop back to William James's advice about countering "mental stimulation with some kind of form of mental relaxation"; his talk on The Gospel of Relaxation, which he delivered @ Bryn Mawr in 1907, and which we'll be discussing in class this coming week, is a clear demonstration of that advice, since he addresses explicitly there "the over-contracted person," and her "over-tense and excited habit of mind."

So I repeat to you, in that context, the queries I lobbed @ kjmason: how much you think depression might be specific to, or particularly exacerbated by, the particular environment in which we find ourselves here: the hothouse of a small, intense liberal arts college, where a premium is placed on performance? I'm thinking here of some of Paul Grobstein's observations about the relationship between depression and analytic/ academic/ intellectual work: that it can offer, for example, a danger in "thinking too much," in spending too much time reflecting.

Where I'd also invite further conversation would be in your linking this historical work to our own class conversations about the psychology, philosophy and pragmatism of William James. How might the themes of his life-and-thinking that we have been tracing be understood differently, or more completely, through the lens of his "nervous exhaustion" and "tired nerves"? We've framed our discussion familially, and culturally, and historically, and psychologically--through his depression--but not medically, through his neurasthenia. How might our understanding of James's ideas be altered, by the use of such an interpretive frame?