Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

What is in a name? That which we call an adaptation.

In the past the thought of a film adaption of a novel brought so much joy to my heart that I could barely contain the excitement. I hoped that by seeing my favorite characters brought to life on screen people like my sister, who did not enjoy reading, would be able to understand my love for the novels. Movie after movie was a disappointment. Ella Enchanted, “O”, Harry Potter, Cruel Intentions, The Joy Luck Club, North Country, Apocalypse Now, To Kill a Mockingbird, etc. I either found myself whispering “that never happened”, or “I promise it was much cooler in the book”. Frankly my heart could not take it anymore. I stopped hoping and learned to expect the worst.

![]()

When I started watching Persepolis the movie I was pleasantly surprised at seeing that the film was in black and white. As the movie progressed a smile would secretly crawl on my face as I saw the film was in French and the Marji I knew and loved from the graphic narrative was the Marji on my screen. By the time the credits were rolling I found myself satisfied with the adaptation but, I did not love it as I did the graphic narrative. At first I did not understand what went wrong. The characters were the same as the ones in the graphic narrative. The dialogue was the same. The plot was the same. Even the the animation was the same as the art in the graphic narrative. It was too much of the same!

![]()

Although I do understand Satrapi's desire to remain true to her original piece of work, not everything that is created and written on a page translates to the screen. At times what is written in a book should remain in the book because it could never have the same effect on film.The medium of film offers new possibilities as to how one can represent a book and the director should take advantage of the opportunity. Sound tracks, special effects, transitions, animation, and actors can be the tools that one needs to transform the events in a book to a wonderful movie. On the other hand, taking too much artistic freedom can result in a blotched version of the novel where a reader watching the movie asks themselves “wait, this movie is based on what book exactly?”. Similar to a remix, a successful film adaptation is one that respects and maintains the essence of the text while at the same time adding flair that was not always present.

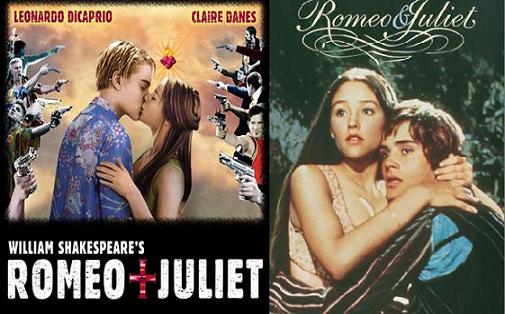

William Shakespeare's epic romance Romeo and Juliet is possibly one of the most famous plays in the history of literature and as result there are hundreds of television and film adaptations. The most popular versions being Franco Zeffirelli's 1968 Romeo and Juliet, and Baz Lurhmann's 1996 Romeo+Juliet.

The Zeffirelli version lacks originality as it is a direct copy of the text to the screen. The costumes, weapons, dialogue, locations, and the characters stay completely faithful to Shakespeare's play. Overall, it is an well-made movie version with talented actors as well as a talented director. The only issue I have with such a movie is that if the content is the same between the play and the movie, then I have no reason to watch the movie as I would much rather read the play. The movie should offer something that the play cannot or else there is no point of having a film version. Unlike Zeffirelli, Lurhmann has no problems whatsoever exercising his artistic freedom in his Romeo+Juliet. His version creates a more diverse and modern Verona in which the Capulets and Montagues fight with guns rather than swords and dress in contemporary clothing. One could say Lurhmann updated the play and brought it in to the 20th century offering his audience of viewers a Shakespeare that relates more to their own personal lives.

Romeo drives a convertible, Juliet marries dressed in white, Mercutio dies on a beach, and Tybalt is killed in a car crash.

The changes never really cease but, despite all the changes to the original play, the important components that make Romeo and Juliet so iconic are still visible on the screen. The dialogue, the balcony scene, the plot, and the characters remain unaltered.

More importantly, the essence that is Romeo and Juliet is still intact because the romance, the passionate kisses, the youthful innocence, and the tragic sorrow is present.

Another remix that is less radical in it's changes is Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings trilogy. Jackson being a very devoted fan of the author J.R.R. Tolkien states:

“We made a promise to ourselves at the beginning of the process that we weren't going to put any of our own politics, our own messages or our own themes into these movies. What we were trying to do was to analyze what was important to Tolkien and to try to honor that. In a way, we were trying to make these films for him, not for ourselves.”

That being said, Jackson retained the elements and characters that made the books so well known, such as the language of the Elves, but was also able to distinguish the sections of the novels that belonged to the novel and not onscreen. He also was able to use tools of film medium, such as soundtrack and special effects, to leave his personal mark on the trilogy. Jackson's remix of the Lord of the Rings trilogy received is possibly one of the most successful film adaptations ever created and outstanding reviews across the board (as well as eleven Oscars).

Pleasing the masses of readers and movie watchers is nearly impossible to say the least. No one will ever be truly satisfied with an adaption of their beloved books, and no movie watcher wants to pay money to see a dull representation of a novel. A successful adaptation should be similar to a remix where a balance between mimicking the book word for word and forgetting the original source must be found. Unfortunately there is no set formula in order to achieve this elusive balance, but at least we have trial and error.

Sources

1.Romeo and Juliet. Photograph. Teach with Movies. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://www.teachwithmovies.org/guides/romeo-and-juliet-DVDcover.jpg>.

2.Romeo + Juliet. Photograph. Literacy Advisor. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://literacyadviser.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/romeo-and-juliet1.jpg>.

3.Olivia HUssey. Photograph. Photobucket. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://i176.photobucket.com/albums/w185/cassia12/Olivia_Hussey2.jpg>.

4.Claire Danes. Photograph. Blog Spot. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_yzyslK4e7wM/SohL1PE1ohI/AAAAAAAAABU/37s-3q7onqg/s400/Claire-Danes---Romeo-Juliet--C10103871.jpeg>.

5.Romeo. Photograph. Fan Pop. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://images2.fanpop.com/images/photos/7000000/Romeo-Pic-1-romeo-montague-7013237-888-455.jpg>.

6.Romeo 2. Photograph. Quizilla. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://quizilla.teennick.com/user_images/X/XR/XRO/xRosethornx/1178759870_Romeo.jpg>.

7.Romeo-and-Juliet. Photograph. Word Press. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://lisawallerrogers.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/romeo-and-juliet-1968.jpg>.

8.Wedding. Photograph. Flixster. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://content6.flixster.com/photo/71/62/38/7162384_gal.jpg>.

9.Don't Judge a Book. Photograph. ZCache. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://rlv.zcache.com/dont_judge_a_book_by_its_movie_mug-p1689972484392913352om5b_400.jpg>.

10.Filming a Book. Photograph. Weekly Reader. Google Images. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. <http://www.weeklyreader.com/readandwriting/content/binary/filmofbook.jpg>.

Comments

"Don't judge a book by its movie"

TBP1988--

I begin my response by repeating your two opening visual quotes--they are just so cute, so apt as illustrations of the story you are telling here. I follow that opening by directing you to Herbie's essay, The Book and the Film Should be Friends, which argues, much more emphatically than you do, that adaptations must "closely follow the original," that their value is directly measured by the amount of detail transferred from book to film. And I follow that direction by sending you both on to a summary essay on the field of adaptation studies, which traces the "pervasive legacy that haunts adaptation studies: both the assumption that the primary context within which adaptations are to be studied is literature," and "the notion that adaptations ought to be faithful to their ostensible sourcetexts."

The bottom line of this review essay is that adaptation studies needs to problematize the "evaluative problems the field has inherited from literary studies—fidelity, hierarchy, canonicity"; that theorists of adaptation should look "more closely at the ways adaptations play with their sourcetexts instead of merely aping or analyzing them," and so replace the questions about appropriation and adaptation with what was once called "intertexuality," but might now more accurately seen as "intermediality."

What might such a re-ordering do to your claims (for instance) that a "successful film adaptation is one that respects and maintains the essence of the text while at the same time adding flair that was not always present," is "similar to a remix where a balance between mimicking the book word for word and forgetting the original source must be found"? Is your essay anticipating the new directions in this field? Or are you holding on to notions of the "iconic," of "essence" and of "honor" which the field of "intermediality" would not acknowledge?