Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Dear Middleschoolers, Love, Charlie

Dear boys, girls, and those of you who just aren’t quite sure yet (because that is totally cool too),

For many of you, this is a confusing time. Things are growing in places where you aren’t sure if they are supposed to be growing, new places might develop novel smells, and you might start to feel differently. If any of these things apply to you, or if none of these things apply to you, you are still normal. Every body goes through different changes at different speeds and in completely different orders. So if your best friend is growing armpit hair, but you haven’t reached that point yet, don’t worry – we all catch up in the end! I am writing to you, middle-schoolers, because this time can be a bit scary; there are a lot of changes that you can expect in the next couple of years, and a lot of information out there, both true and false, so a quick guide to the next few years seems like a pretty good resource for you right about now. Read on to learn about what makes boys and girls different biologically, some of the changes that you can expect to your body during puberty, how babies are made, and a quick peek at the different categorizations of gender!

Let’s start from the very beginning. How did we get here and what exactly makes girls different from boys?

The process of how an egg is fertilized is the best race out there, bar none. A woman produces many millions of eggs as a fetus herself, stabilizing at two million by the time that she is born. After she hits puberty (we’ll get back to that one!), she begins to release one egg a month, every month, known as menstruating (or her period). Along with releasing the egg, she also discards the old lining for the egg, which is comprised of tissue and blood (Roughgarden 188). As for the sperm piece of the equation, men are born with some sperm, but continue to create more continually, as well as releasing sperm on a regular basis. (Hey boys, those times that you wake up in the morning and you’re bed is kind of wet and sticky, that’s what your body is supposed to be doing – it is releasing some of the older sperm so that it has space to store the newer sperm – so fret not!) When a man and a woman have sex, the man ejaculates, or releases, sperm into the woman’s vagina. The sperm swim towards the woman’s egg, which is waiting further up her vagina in a part of her body called the oviduct (Roughgarden 190). The egg thins its outer layer so that a sperm can attach itself. Once one sperm attaches itself to the egg, the egg changes its surface so that the other sperm give up trying to attach themselves as well. This means that the egg is now fertilized. The fertilized egg, called a zygote, begins to divide internally, and begins the process of growing into a fetus (Roughgarden 191). The baby-growing process is divided into three trimesters. The first trimester includes the creation of the baby’s sex and the beginning of the development of the baby’s organs. The second trimester is when the baby can officially be called a fetus. At this point, the fetus will have arms, legs, and begin to look human! The third trimester is all about brain growth. And then, the baby is ready to be born! (Neat, huh?!) (Roughgarden 194).

As an embryo in utero, we are all the same gender. The sex of the embryo is determined by whether the “primordial germ cells mature as eggs or as sperm” (Roughgarden 167). Gender differentiation begins with the gonads, and whether they turn into testes or ovaries. The gonads are the site in which testosterone and estrogen are produced. From there, the body begins to mature into a male or a female (Roughgarden 196-7). The next key player in the game of “which gender will the embryo be” is SRY. SRY is a gene on the Y chromosome. SRY either takes over the embryo, creating a male, or without SRY, the embryo become a female. However, none of these steps alone determines gender (Roughgarden 198-9). While these are not the only steps in creating the sex and gender of an embryo, they are the basic steps. There are many different points in which certain hormones or chemicals override others, and the embryo then takes a different route to finding its gender. For more information on the nitty-gritty science behind the world of how exactly an embryo’s gender is created, head on over to your local library and do a little extra reading.

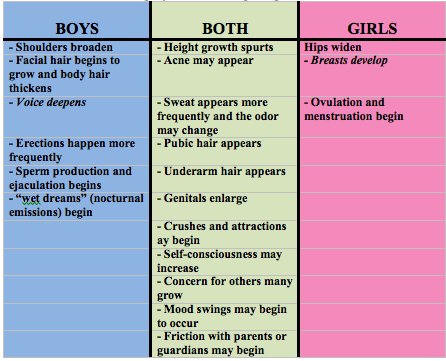

So, assuming that you’re still following, you’re probably wondering what happens next, right? The next stop on this maze through gender and growing up and all of the pit stops in between is puberty. (Of course there are a whole bunch of scraped knees, yummy snacks, first steps, maybe some siblings, et cetera along the way). Puberty can best be described as “a time when a person’s body, feelings and relationships change from a child’s into an adult’s” (FLASH 9-3). Puberty happens at different times in different people’s bodies, which makes pinpointing an exact starting point next to impossible. That being said, most girls will begin to see changes to their bodies between ages 9 and 16, and boy will generally begin to see changes to their bodies between ages 10 and 16 (FLASH 9-3). These changes are kick started into action because of the pituitary gland, which is found in the brain. The pituitary gland is basically the master switchboard operator for the body, controlling just about every kind of function from growth to sex hormones to temperature regulation. So what are these changes of which I speak? Well, they differ from boys to girls with a few changes which will overlap. Because there are so many changes, instead of writing out a list, I have made a chart to help to better understand what changes you should be expecting.

* Italicized terms apply to both genders, but predominately apply to the gender in which they are categorized

** items in the chart are taken from FLASH 9-3 – FLASH 9-6

All of the changes in the chart are normal. They can happen in any order, and at different times. If you ever have any questions about your changing body, be sure to ask someone! Ask a grown up, a parent, a teacher, or a doctor. Be wary of searching for things on the internet because then you can’t be sure that the information that you are getting is true. If after the age of 17 you have found that your body hasn’t gone through any of the changes in the chart, then its time to go a see a doctor, just to make sure that everything is working correctly.

The last thing to cover, in brief, is gender. Many consider there to be a gender binary, meaning there are only two genders – male and female. However, for some people, these categories are too loosely defined. After going through puberty, or even while going through puberty, you might notice that you look at yourself, and others, in a different way. Some people are comfortable as just “male” or just “female”, some are born with tricky genitals and it is unclear if they are a boy or a girl. These people are called “intersex”. Others are born as a biological male, but feel they should have been a woman, or vice versa. These individuals are called “transgender”. Some of these individuals make a more permanent change and use hormones and surgery to fully switch to the other gender. These individuals are called “transsexuals”. Sometimes, people aren’t really sure which gender they want to fully commit to, and change each day, based on clothing, or choose to dress in a gender-neutral fashion, and these people are called “gender queer”. Whatever label, or non-label, you choose to affix to yourself is up to you. If none of these labels seem to fit just right, create your own! Only you can really know which label fits you best. And if that label changes in six months, six years, or never, that is cool too. It is wholly up to you.

I hope that this letter is helpful to you. I realize that this can be a difficult, scary time with all of the changes that your body is going through. It is also intimidating if you are the first or the last person in your grade or group of friends who goes through these changes. If you are that person, don’t worry. Everyone else will either catch up to you or you will catch up to them. You will still be able to accomplish everything in life that you wanted to, whether you entered puberty at 9 or at 16 (or even later). Don’t spend time worrying about what is happening to everyone else’s body; instead, focus on the beautiful individual that you are growing into and getting to know.

With love and advice from the future,

Charlie

Sources:

Family Life and Sexual Health (F.L.A.S.H.) curriculum, Public Health – Seattle & King County. www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/personal/famplan/educators/~/media/health/publichealth/documents/famplan/G456_L9.ashx

Roughgarden, Joan. Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Comments

Entangling

Charlie--

Many of your classmates also took on the education of middle-schoolers this time ‘round; check out (for starters!) Gavi’s Rainbow of Sex Difference, jfwright’s Beginning Book about Sex and Gender for Trans* and Intersex Kids, Katie Randall’s Template: and phenoms’ Lesson Plan. I'm encouraged by all these letters to the future!

Your own letter is distinctive in its insistently binary framework (“Dear boys and girls, and those of you who just aren’t quite sure yet”); in its presumptions about normal sex development (“just to make sure that everything is working correctly,” vs. those “tricky genitals”); in its valorization of individual choice and will (“It is wholly up to you…You will be able to accomplish everything in life that you want to”); and in its mash-up of sex and gender: "Gender differentiation begins with the gonads, and whether they turn into testes or ovaries" (this is actually sexual differentiation); "Many consider there to be a gender binary, meaning there are only two genders – male and female" (male/female is a sexual binary); "For more information on the nitty-gritty science behind the world of how exactly an embryo’s gender is created" (but an embryo does not have a gender).

So I find myself wanting to say again what I said last month, that I’m puzzled by how absent--the-context of this class this letter seems to be. There’s no trace of our questioning of the binary, or of the oppressiveness of norms, no acknowledgement of the social construction and limitations on individual choice that we’ve been examining so insistently in our conversations, no recognition of the difference between sex and gender.

The last time we were “talking” about this on line (when I questioned your choice not to use much of the class material we’d discussed, in your exploration of the increased freakishness and increased agency of a series of portraits of naked women), you responded w/ a very thoughtful piece about the dangers of misrepresenting others when using their work out of context. Kaye added a few complicating questions to the conversation—“ How can we honor texts that catalyzed our thoughts, especially when our ideas contradict the original writer's? …Does every statement need to begin with a caveat and a statement of the writer's standpoint? Can't we ever just get to our point?” And now we have both Judith Butler and Karen Barad, reminding us about the great difficulty of “disentangling” who we are from those with whom we are in relationship. In Chapter 2 of Precarious Life, which we’re reading for this week, Butler suggests that “the attachment to ‘you’ is part of what composes who ‘I’ am”; and throughout her work, Barad asks us to consider the possibility that "'we' have 'intra-actively' written each other...an iterative and mutually constitutive working out."

I love that you are sending love and advice from the future to your imagined audience of middleschoolers. It's because this talking-across-time is so important that I'm also wanting you to send them advice more entangled w/--supported and buttressed by, or @ least more deeply engaged in conversation with--the material we’ve been engaging together in this class. Might the "anxiety of normalcy" be balanced less by assuring children that they are normal, not by pink and blue columns, more by celebrating "the beauty of diversity,” a rainbow-like spectrum?

This American Life: The Middle School Edition!

Charlie,

I thought this was GREAT and I loved your idea - middle school is such an awkward, drama-filled, hopeless time, and I wish I'd had more support or kind words from young men and women who had gone through the same things. I was listening to NPR's This American Life this morning, and their newest episode is all about - lo and behold - middle school! Episode one talks a bit about the biological changes going on that contribute to making middle school an especially difficult time. You can listen to the episode online for free at their website!