Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

The Medical Treatment of… gayness?

In the New York Times Magazine in June an article was published entitled “Living The Good Lie,” a narrative about therapists who help people stay in the closet. Many individuals who have homosexual urges do not want to “come out,” usually for religious, familial, or social reasons; these therapists help them with this. They argue that for people for whom faith plays an inordinately large role in their lives, it would be more damaging for them to lose their place in the community of their faith than to subdue their homosexual feelings. By acknowledging their feelings to themselves but not acting upon them, they are “cured.”

Ex-gay camps and organizations supporting ex-gay therapy, such as Exodus International and Homosexuality Anonymous, have been in existence since the 1970s. These groups use various methods from counseling to electroshock therapy to sexual abuse, and continue to try to “convert” individuals from a life of homosexuality towards Jesus, despite warnings from the American Psychological Association on the trauma and damage that such therapy can cause. A few years ago the Catholic Church headlined their successful members who were “cured” from SSA (struggle with same-sex attraction), and still preach their successfulness despite the fact that most of these members recanted, saying that they were pressured by the church.

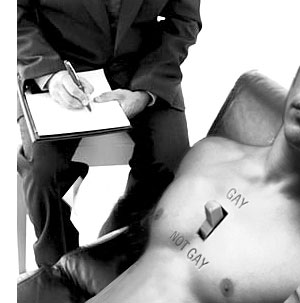

I do not support ex-gay therapy, and I believe that denying who you really are can only end up causing harm not only to the individual themselves but also to family and community members. I would, however, like to explore how homosexuality has been medicalized as a condition, and look at how and when the brain responds to stimuli. In other words, can what gives us pleasure be altered by examining the brain and observing what triggers what we find to be pleasurable?

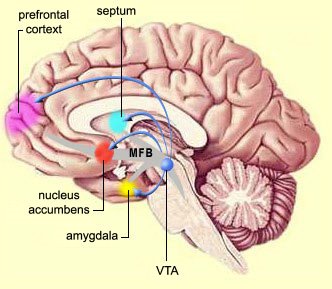

The regions of the brain involved in pleasure are commonly referred to as pleasure centers; structures contributing to pleasure are primarily the prefrontal cortex and the nucleus accumbens. Research has shown that if an electrode is implanted into the medial forebrain bundle of a rat, when it is placed in a Skinner box it will press a lever to self-stimulate about 10,000 times an hour without stopping. In fact if a rat is left in a Skinner box with food and water 24 hours a day, the rat will develop a work-sleep cycle but will starve to death, refusing to stop the brain stimulation to eat or drink. The rats will also overcome obstacles such as shocks to get brain stimulation that they will not overcome for food or water.

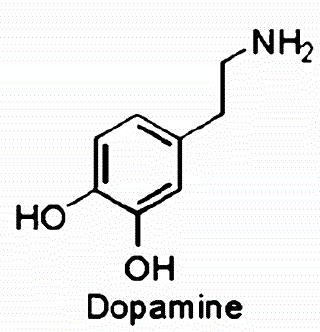

When we experience pleasurable things such as food, sex, and drugs, dopamine floods the pleasure centers, reinforcing such activities. The more dopamine you release, the more you want, or crave, something. A Dutch scientist looking at the brain of a man orgasming saw the same flood of dopamine into the brain as a heroin addict experienced with a heroin rush. And similarly to drugs, you can build up a tolerance to this rush of dopamine; here romance comes into play, because if a relationship is purely sexual you will eventually not get a “high” (just as a heroin addict will need to up levels of heroin to experience a rush once tolerance has been developed) and will lose interest in a person. So by changing dopamine levels, can we change who we are attracted to?

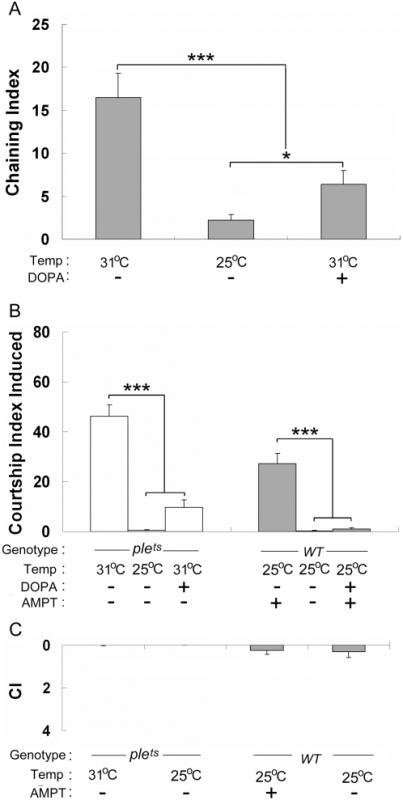

In looking for research on a link between dopamine and homosexuality I found an article entitled “Reduction of Dopamine Level Enhances the Attractiveness of Male Drosophila to Other Males” where neuroscientists varied dopamine levels in Drosophila and observed sexual interactions. Tyrosine hydroxylase is the rate-limiting enzyme for dopamine synthesis, and the Drosophila that were used had a temperature-sensitive allele that encodes tyrosine hydroxylase. They raised some males in an environment with a temperature of 25° C and a second group of males in an environment with a temperature of 31° C. Tests revealed that the males who were raised at 31° C had “significantly lower levels of [dopamine] as compared with sibling males raised at 25° C.” Males raised at 25° C (higher dopamine) also showed rare male-male interaction while males raised at 31° C (lower dopamine) showed increased male-male interactions. The experiment was done both with the Drosophila being fed supplemented food and without supplements.

The neuroscientists wanted to study the individual behavior of each Drosophila partner and so they measured the courtship index (CI) between males raised in the two temperatures and with the two different food regimens. This was to “confirm the implication of [dopamine] reduction in male homosexual attractiveness (the male tendency to stimulate the courtship of other males, as opposed to the male propensity to court other males).” It was found that while dopamine could be a contributing factor in male-male courtship, it did not hold equal weight for all types of Drosophila, and it was not the only factor; chemical signaling was also found to affect courtship behavior.

At the University of Illinois at Chicago a team of neurobiologists found that “sexual orientation in fruit flies is controlled by a previously unknown regulator of synapse strength” which led them to the successful turning “on” and “off” of homosexuality in Drosophila using genetic manipulation or drugs. They also discovered a gene that they named GB, or gender-blind, that contained a mutation that turned the Drosophila bisexual. They also found that the GB gene was connected to scent and the perception of pheromones, which are sexual stimuli.

While clearly there is still a great deal of research to be done on the biological structures related to sexual attraction, as you can see the idea of medically changing sexuality is something that neuroscientists are already actively pursuing. If, for example, a drug became available that could change sexual orientation, what would that mean for the LGBT community? Like the deaf community who sometimes laments the hearing aids implanted in children today, would the LGBT community lose some of that community and cultural identity? What would the public reaction be to the idea that what gives us pleasure can be “treated?” Drosophila are a long way from humans, but as we are learning in our readings what holds true in one species usually holds true in others. For now all we can do is wait and wonder, watching while what we thought we knew about gender and sexuality continues to be rewritten. What hand will be delt next?

Comments

Drugs solutions only address the SURFACE

Very interesting information. However, I think science is missing the mark on this. Dophamine is clearly associated with the brain's rewards system. Of course, a lot of it either stimulates more craving or lessens them. But, what's missing here? Our THOUGHTS. The chemical was emitted because on pleasures that the person indulged in. This emits dopamine when TRAINS the body to like certain things. So, if we don't do those things to begin with (homosexuality) and don't let our curiousity get the best of us...we will never develop a dopamine addiction to them. Of course, science can develop a drug to reduce dopamine levels...and that might help sexual craving, but clearly dopamine affects other motivations in human behavior besides sex. If you try to stop just the sex part...you might make the position not goal oriented at all. In other words, drugs are not always the best solution. We don't know how all the body's chemicals interact. For now, the best solution is to seek theraphy to redirect improper sexual yearnings...in the right direction. The same thing can be done with food addictions. Willpower is important.

sexual attractions is switch " off and on"?

i'm so interested for the studies and research that you guys are trying to come up with conclusion, not because i'm neurologist but because i'm one of thousand man who's suffering of homosexuality that are craving to get rid and become a straight one. I'm glad that there's any possibility that the problem i'm in countering now is nearly to come up with solution.keep up the good job. im looking forward of the better and successful conclusion of your study.

i do not believe that gayness

i do not believe that gayness can be cured. im almost 16 and im bisexual i fought if for years and all it did was kill me inside. im so much happyer now that ive come out and accepted it.

dopamine and sexual attraction

As a fellow biologist, I appreciate how you examined sexual attraction through the lens of your own academic work in neuroscience. You introduce new genetic research on Drosophila by highlighting how past therapeutic approaches for changing "same sex attraction" in humans have ranged from "counseling to electroshock therapy to sexual abuse," are not always imposed on others, and have largely been ineffective. You then suggest that new understandings of the role that the neurotransmitter dopamine plays in pleasure-seeking behavior raise the possibility that less crude methods, which are pharmacologically based, might eventually be developed for changing sexual orientation. I'd also like to thank you for acknowledging that understanding the molecular genetics and neural pathways of courting in fruit flies does not mean that a pharmacological "treatment" for gayness is around the corner!

However, I wonder if the crudeness of current conversion therapy methods is the primary problem for many people? Subjecting someone to shock therapy or sexual abuse is often seen to be abhorrent, but would objections to conversion therapy diminish if the therapeutic methods were pharmacological--if psychiatrists could prescribe a pill to change someone's sexual orientation? I think more people need to understand the complexity of the bio-psycho-social networks that undergird behavior and that any intervention (talk therapy, pharmacology, electroconvulsive therapy) can have negative unintended side-effects on individuals. You raise the stakes on unintended consequences beyond individual bodies to communal bodies by asking what does the medicalization of sexual attraction do to the LGBTQ community? This is an important issue that already plays out in other areas of sexual diversity such as intersexual bodies.

I look forward to continued conversations about the biology of sexual diversity and would appreciate links to the orignal research articles as well as citations to the claims you make in your introduction. The graphics you included are quite striking--I especially like the LOVE hand of cards--but I was unable to interpret some of the graphs you showed--e.g., what is a "chaining index"?