March 6, 2015 - 16:28

For the longest time I considered myself a 'science person' (along with an attendant sense of achievement). I was oblivious to the extent to which my personal opinions and beliefs framed my view of the world, what I wanted myself to be, and to be viewed by others. In participating in this course I realize now how utterly subjective my framing of science is, with my opinions interpreting my experience. I realize that it takes a lot of faith to be placed in the subjective in order for me to be objective.

The objectivity of science and the subjectivity of the humanities, I now believe, are integrally related. No person lives completely in the objective world of science, just as there is no person who lives completely in a world of inferences and emotions. Even people who have devoted their entire lives to a narrow slice of scientific investigation are guided by emotions that affect the way they conduct their experiments. In considering medicine as a possible career option, one of the things I am told constantly is that doctors simply can’t be emotional - that personal emotions (as though there are societal emotions) should not play a role in their diagnosis. The funny thing is, they do so anyway. When considering whether someone should undergo surgery, doctors are expected to advise patients taking into consideration their age – not as a measure of fitness and of the potential recovery time, but also whether it is worth it. Who decides for whom, what’s worth or not? While the patient’s family often plays a role, it’s the doctor on whom the families have placed shamanic trust that is expected to be providing unbiased opinion. Doctors, men and women of science, routinely make decisions guided by science and colored by emotional judgments. It is less that they are objective, but more importantly (that I now see) that men of science are seen to be objective.

I was originally going to write this paper on the stark and ever-lasting differences between science and the humanities. It is said that people in science value logic and rational explanations - by rational I mean using available knowledge to piece together an acceptable narrative of what’s happening - and people in the humanities value emotions as ways of interacting and negotiating with the world, and drawing sustenance and meaning - that logic is merely value laden, and hence not a special category to be valorized. But the more I read Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide, and review its characters and their decisions, the more I find that the polarity of science and humanities is a caricature of convenience; the more they depend on each other in order to enable a distinction to be. The subjective and the objective are convenient pegs, on which we hang the tapestry of our lives.

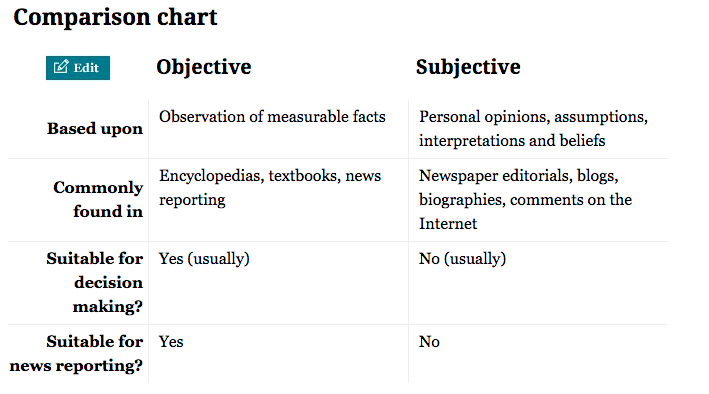

The first thing that came up when I searched “subjective vs. objective” was this chart:

How could I have ever believed that the two columns were insular and independent of each other? What was I thinking? Isn’t a “measureable fact” based on a socially agreed construct? If objectivity is the star lode for decision-making, why is it that CEOs are expected to have high emotional IQs? From a young age we’re taught that Math is objective - it isn’t influenced by personal feelings or opinions, and that English is subjective - influenced by personal feelings, “taste”, and opinion. What didn’t strike me until recently was that even in Mathematical discoveries, subjectivity plays a huge role. When a new formula is discovered (or is it invented?), what constitutes mathematical “elegance”? Especially in a field like Math, there are always multiple pathways to the (same) solution - the path one takes is based on “intuition” and not rigorously articulated by mathematical vigor. In the peculiar dichotomy that we maintain, where does “intuition” fit in? The sum total of each individual's subjective experiences forms their reality, and social reality is the aggregation of individuals’ reality.

In The Hungry Tide, by Amitav Ghosh, we are asked to imagine Piya as the scientist and Kanai as the linguist.

“Piya knew that if she could establish any of this she would have a hypothesis of stunning elegance and economy—a thing of beauty rarely found in the messy domain of mammalian behavior…But the hypothesis begged as many questions as it answered. What, for instance, were the physiological mechanisms that attuned the animals to the flow of the tides? Obviously, it could not be their circadian rhythms since the timing of the changed from day to day. What happened in the monsoon, when the flow of fresh water increased and the balance of salinity changed? Was the daily cycle of migration inscribed on the palimpsest of a longer seasonal rhythm?” (Ghosh 104)

In reading this passage, it is immediately clear that Piya’s manner of thinking is what is commonly accepted to be that of a scientist. Marshaling of facts for their relevance to a given problem, and rejecting explanations that cannot be explained by known facts. From a young age, I was taught to question things around me: how do you know that the colors you see are the colors that exist? Why do I have to drink milk in the morning? How is it that I am a human, and my sister is not an ant? To me, questioning seems to be the essence of science. Challenging statements that were considered as a given, yielded nuggets of knowledge of the specifics under questioning, and also framed the meta particularities of my “scientific” world view. However, each question we ask, regardless of how scientific it may seem, is subjective. Where do the questions come from? Why does Piya focus on physiology and not anatomy of the Orcella? Where is her urge to question, investigate and categorize her world come from? Is that objective as well? Or is it beyond the objective-subjective dichotomy? Clearly habits of the mind are guided by what’s valorized, but are not solely it’s influence.

In their specific traits, Piya and Kanai have “decided” to direct attention more in one direction than the other. While Piya examines the present, Kanai sets out to discover the region’s history. Although traveling to the same islands, one is going for a “scientific purpose” – aided by a grant; the other seems to be on a quixotic journey, to discover and retrieve a notebook of a deceased uncle. What motivates each?

Kanai said, “For him it meant that everything which existed was interconnected: the trees, the sky, the weather, people, poetry, science, nature. He hunted down facts in the way a magpie collects shiny things. Yet when he strung them all together, somehow they did become stories — of a kind (Ghosh 223).” In a way, Nirmal’s thoughts obfuscate the science vs. humanities dichotomy, and hint at the co-existence and co-dependencies that are necessities of this world.

By the end of the novel, it becomes clear that the character traits the Piya has do not fall under a distinct category – although she is a scientist, some of her thought processes follow those of a more humanities oriented person. At the very end of the book, Ghosh writes, “’You know, Nilima,’ she said at last, ‘for me, home is where the Orcaella are, so there’s no reason why this couldn’t be it” (Ghosh 329). It seems as though Piya is finally addressing the fact that unlike a stereotypical scientist who has a lab and only works there, she has to be willing to have a mobile home. People tend to always associate writers, journalists, and linguists as not being stationary but when it comes down to it, there are no pure science or pure humanities fields – everything is intertwined.

The question I keep coming back to is whether or not it’s possible for subjectivity to exist without objectivity. Objective information reviews many points of view and is intended to be unbiased, but who decides whether or not something is unbiased? Is that not then subjective?

Ghosh, Amitav. The Hungry Tide. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2006. Print.

"Objective vs. Subjective." Diffen. 1 Jan. 2015. Web. 4 Mar. 2015. <http://www.diffen.com/difference/Objective_vs_Subjective>.

Comments

The Two Cultures, or One?

Submitted by Anne Dalke on March 14, 2015 - 12:20 Permalink

asomeshwar--

Last month, you created an “eco-zine,” as an alternative to “a learned exegesis that is linear with a single dominant voice.” This month, you’re doing something related: digging into the difference between the ways of knowing, acknowledging the subjective basis of science, less so the objective dimensions of the humanities…;)

This is a topic that has long interested me; my first foray onto Serendip was in a faculty discussion of The Two Cultures (when I hypothesized that scientists are continually repeating-&-comparing stories/experiments, in a search for truth claims that are broadly replicable, while humanists are engaged in tracing the "special structure of exemplarity" of each text).

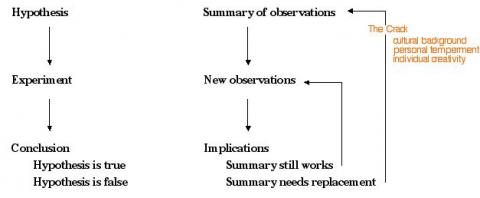

You’ll find lots of other explorations of these ideas on Serendip; my friend Paul used to argue that what distinguished the process of science (or, more generally, all empirically/inductively derived understanding), is testing all current summaries of observations with cultural biases, personal temperament, and individual creativity:

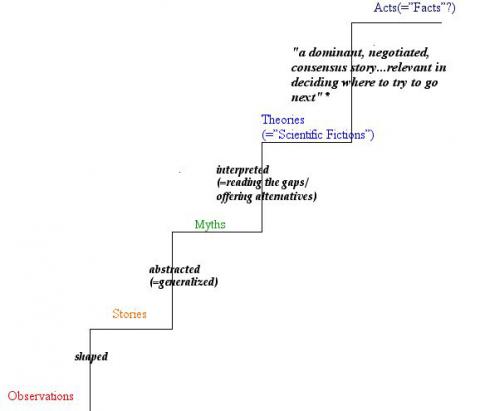

I argued, elsewhere, that “facts” were “acts” of negotiated consensus:

Both of these charts envision (and figure) a sort of “disciplined subjectivity,” which might be another way of challenging the dichotomy you query here.

As you think some more about whether you’re heading to medical school, you might also want to check out Atul Gawande's Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. It’s a profound critique of the subjectivity (and fears) of physicians who can not face the “fact” of mortality—either that of their patients or of themselves, a failure that has profound social consequences.

I’m also wondering what sort of image might represent your understanding of the two-sidedness of objectivity/subjectivity…perhaps an ambiguous figure?

P.S. You need to go back and tag both your web-events as such; you’ll see that otherwise they don’t stand out in your portfolio as they should.

asomeshwar and Purple Finch—

give a look @ (and comment on?!) your explorations of subjectivity and objectivity!

I've actually read not only

Submitted by asomeshwar on March 16, 2015 - 21:13 Permalink

I've actually read not only Being Mortal, by Atul Gawande, but his other three books, The Checklist Manifesto, Complications, and Better, as well! I thoroughly enjoy his writing because I feel like it perfectly fits into the 'in between' of the subjective and the objective.

With regards to what image might represent this understanding, I was reminded (for some odd reason) of a sycamore tree I had seen an image of once, that was referred to as a "circus tree." The way the trunk developed makes it seem like there's no beginning or end and no right or wrong, similar to how I've discovered the subjective and objective play a role in the humanties and in science.