November 3, 2006 - 18:56

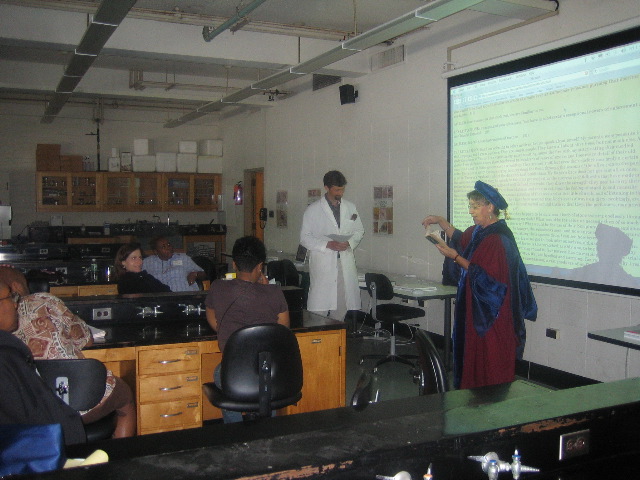

I have for many years used, as a keystone in a first-year writing course I co-designed and co-teach @ Bryn Mawr, a phrase from Scene 8 of Bertold Brecht’s play Galileo: “blest be the land that needs no hero!” Galileo says this, when his friends express their disappointment that he has not held out against the Inquisition (to the right is a performance this scene for a Summer Institute for K-12 teachers). “Blest be the land that needs no hero” is a phrase that my students need some time understanding, much less accepting. We generally arrive at an agreement that Brecht is warning against looking to others as ideals, as models or representations of the good. Rather than blaming others for their cowardice or failure to live up to our ideals, to fulfill our needs, we should look to ourselves.

I have for many years used, as a keystone in a first-year writing course I co-designed and co-teach @ Bryn Mawr, a phrase from Scene 8 of Bertold Brecht’s play Galileo: “blest be the land that needs no hero!” Galileo says this, when his friends express their disappointment that he has not held out against the Inquisition (to the right is a performance this scene for a Summer Institute for K-12 teachers). “Blest be the land that needs no hero” is a phrase that my students need some time understanding, much less accepting. We generally arrive at an agreement that Brecht is warning against looking to others as ideals, as models or representations of the good. Rather than blaming others for their cowardice or failure to live up to our ideals, to fulfill our needs, we should look to ourselves.This ringing phrase, and the discussions it has engendered over the past five years, have come back to haunt me this week. We came to Monteverde less for its famous cloudforest reserve, than because of the history of the Quakers in this area: four draft resistors, all young dairy farmers, were told by an Alabama judge in 1949, “If you like this country you should obey the laws of this country, and if you don’t like it, you ought to move out…” Thirty-some other family members and friends agreed with them that the U.S. economy had become “so involved with military effort throughout the world that a person can hardly make a living without being a part of that system. Even the price of milk depends upon it.” Wanting to live without contributing to that system, and also seeking a less materialistic place to raise their children, this group moved to Monteverde. Theirs is a story filled with much hardship and difficulty (oh, the stories!); by their own account, they were “heretics” (=in the late Latin meaning of “able to choose,” or dissenters). The community they created in Monteverde still exists, complete with Meetinghouse, bilingual school, cooperative creamery and lots of good fellowship—if still @ some distance from the poorer Ticos in this area.

Far as we’ve been able tell, so far, there are three groups here, which intersect but don’t really interact much socially: the Ticos, the tourists, and the ex-pats. The economic gap between the Ticos and the tourists they service is huge. Yesterday morning, my host mother (who works as a cook in a restaurant serving “Nueva Latina” food) was describing to me some of the details of her hard life. Until 20 years ago, there was no electricity and no water in the houses here. She had six children (in as many years): three @ home, and three in the hospital. The ride to the hospital, in each case, was seven hours long--on horseback—in labor.

When our conversation ended, I went for a walk across the road, and up the hill—into the grounds of one of the huge Swiss-like hotels here: there were whirlpool baths beside each cabin, a massage parlor, beautiful (and very expensive) tables on a spacious patio….another world. Another planet.

And yet the existence of the Quakers here makes me think that it is possible to bridge such a distance. I’m deep into the Monteverde Jubilee Family Album--a wonderful collection they put together for their 50th anniversary, one that honors differing stories, including those of Ticos, rather than selecting individual versions. One of these accounts, by Juan Leitón Villalobos ( who was six when the Quakers arrive) reports that

Blest is this land that has some heroes...