Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Precarious and Performative Play

An "Out of Focus" Utopia

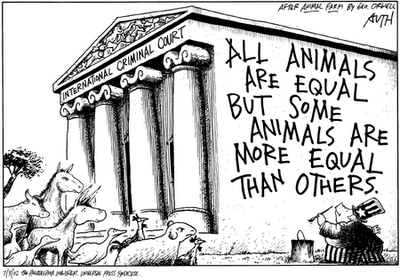

After our discussion ended on Tuesday, I left class still pondering the results of our utopia exercise. While some might think a perfect socio-politico-legal system is easy to construct in theory, I had (and continue to have) trouble conceptualizing a world in which “equality,” a word that implies affording all people the same status, rights, and opportunities*, does not inevitably translate into “sameness,” a word that wipes away all sense of individuality and fails to acknowledge or cherish differences. I’m reminded of Orwell’s Animal Farm, which details first the liberation of animals on a farm from oppressive humans, then the animals’ attempt to set up a utopian society in which all members of the farm are equal, and finally the emergence of a hierarchy in which (spoiler alert) the pigs take control of the farm and reduce the original seven commandments to only one: “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others.”

(An interesting take on the current state of our society...)

Where Words Fail, Music Speaks

At the suggestion of Kaye, here are links to the songs I've used as titles for my previous blog entries. I'll be including a link to the corresponding song in each of my upcoming posts, which can be listened to separately or while you read.

9/3/2011 - "Down By The Water" -The Decemberists

9/11/2011 - "Bitch" -Meredith Brooks

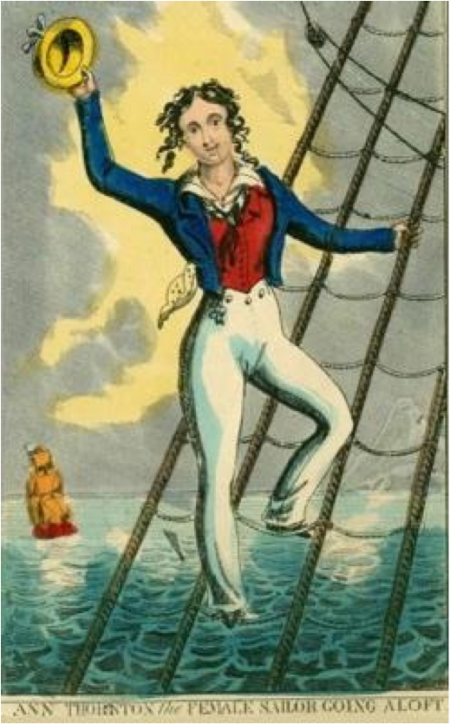

9/17/2011 - "Cape Cod Girls" -New England Sea Chantey (composor unknown)

All The Different Names For The Same Thing

Upon reading the Margaret Price selection from her text Mad At School, I was struck by the necessity we exhibit for a sense of identity. An identity is something that we take on ourselves, something that we can choose to abort or adopt on our own free will. While I may be influenced by those I associate with in my community, no one forces me to identify as one particular thing; it is my own free will that allows me to do so.

I am intrigued by the motifs of identity written about in Margaret Price’s Mad At School introduction. Like Price, I may appear “healthy as a horse yet walk with a mind that whispers in many voices.” Can’t those “voices” be viewed as my many identities? Can I not obtain something unique from each of them, something intriguing with which another individual may identify? Morever, who is to say if I am mad or sane? After all, it does take one to know one.

Disability: The Clash Between Culture and Self

McDermott and Varenne’s essay on cultural constructions of disability nicely supplements Tuesday’s discussion of how we define “norms” and the ways in which norms come to exist in any given society. The class’s thoughts seem to closely mirror McDermott and Varenne’s claim that disability is best viewed as a culturally constructed concept, and we too attempted to picture whether the concept of disability would exist at all if the socially constructed boxes that confine our thoughts, not to mention our world, were lifted.

The Powers of Culture to Disable in Reading Terminal Market

Reading terminal market is a buzzing hotspot for locals and tourists to experience the intra-action of the stirring, culinary melting pot that is Philadelphia. I first traveled here on a date last spring and was pleasantly surprised to discover so many foods and beverages that I like easily and cheaply available. Chicken samosas, mango, banana, and pineapple smoothies, Italian hoagies, Thai fried rice… I could go on! Sitting in the food court, in the heart of the market, amidst the hustle and bustle of the crowds of families, couples, friends, tour groups, band troops, and others is quite an experience.

After reading Culture as Disability, I began thinking about the ways in which spaces of “social interaction” are constructed to create accessibility and/or inaccessibility. I was quick to dismiss the intellectual exercise of thinking about the ways in which these spaces physically create accessibility or inaccessibility, but then realized the mere notion I would consider this a worthless exercise was part of the message of culture as disability that McDermott and Varenne enumerated.

I was in Reading Terminal Market yesterday with my mother, who was visiting me while on business in the area, and found myself observing many ways that the layout and design of the market made itself inaccessible to people with physical disabilities. I’ll flesh some of those thoughts out below, but first want to mention the people I observed who I lumped into this category.

On Deafness and Being Heard

I've been thinking more about what rachelr said in her post and what we discussed in class about the repetitive nature of Eli Clare's book. I remembered an experience I had that helped me better understand the Clare's repitition, so I will share it in the hope that whoever reads it might gain something from it.

Last summer, I interned with a judge who worked with both civil and criminal cases. One of the cases I got to sit in on had been brought by a deaf woman. In court, when a questioning attorney asks a question, the witness is supposed to just answer that question, not add anything else. But whenever this woman was asked a question about what had happened, she not only answered the question; she went on at great length about other details until the judge inevitably cut her off. It was strange and somewhat frustrating. I had trouble understanding why she kept over-answering after both attorneys and the judge asked her to stop.

Questions, questions, questions

“…No group stands alone, nor even in a simple relation to more dominant other groups, but always in relation to the wider system of which all groups, dominant and minority, are a part.”

McDermott and Varenne describe culture as a set of collective norms rather than individual behaviors. Since our last class, I’ve been thinking about what is “normal” – the authors describe assumption that culture is universal as fundamentally flawed because that results in the perception that those who do not confine to those norms are missing something, in effect, “disabled.” The concept of “health” is defined as being “free from illness or injury,” and the origin of the word is related to “whole” – but then, most people are never “healthy” or “whole.” Is it “normal,” then, for the body to be “unhealthy” or not “whole?” Then why do shows like “Britain’s Missing Top Model” exist? Where do we draw the lines between which injuries/illnesses/disabilities are “normal” and which stray from the norm? Does it matter whether or not they are hidden, or how common they are? But then, how do we know how common they are if they are hidden? Normalcy is driven by perception, and, I would argue, in contrast to McDermott and Varenne’s arguments, these perceptions are individual rather than collective, based on one’s own experiences and diffracted upon their own world.

Cape Cod Girls Ain't Got No Combs, They Brush Their Hair With Codfish Bones

I write this entry from the marine science laboratory at Williams-Mystic, a maritime studies program based in Mystic, CT. I spent last semester with the program, which provides an interdisciplinary academic experience for students interested in marine and maritime studies; I also remained here over the summer, where I worked with a professor from the program on an academic paper detailing Virginia Woolf and her first novel The Voyage Out. I'm back once again for Alumni Weekend, having conquered a very late SEPTA train and 4.5 hours on Amtrak with a screaming infant seated in front of me. During the block of time I spent riding up the coast, I thought a lot about what physical efforts I had to make for the weekend. Starting at my room on Merion 3rd, I walked down two flights of stairs and up to the R5. From there, I wove through 30th Street Station, stood in line for my Amtrak train for about 30 minutes, went down two escalators, and got onto my train. Once in Mystic, I had to walk approximately one mile from the train station to the Williams-Mystic campus, pitch my tent (being a poor college student, I'm not staying in a hotel), and finally met up with a friend to go sailing on the estuary.

Posting Part 3/3: A Summary... but not really

I won't attempt to summarize each documentary's interrogations with 'disability' and 'gender.' I do know, however, that each of them helped unhinge my preconceived notions about and subtle prejudice toward people with disabilities and individuals that may not fit neatly into the social construction of the male or female gender, respectively. In both cases, I was confronted by my discomfort in ways that helped me realize that as progressive, liberal, and non-judgmental I may consider myself, I have much still to learn, accept, and embrace.

I plan to rewatch each of these documentaries if anyone would like to get together to watch them for the first time or rewatch them with me... perhaps in preparation for our first web paper posting.

Posting Part 2/3: My Flesh and Blood

My Flesh and Blood

2003 UR 84 minutes

Winner of both the Audience and Directing Awards at the 2003 Sundance Film Festival, this inspiring documentary tracks a year in the life of Susan Tom, a single parent from suburban Fairfield, Calif., who has adopted 11 children with special needs. Directed by Jonathan Karsh, the film obliterates stereotypes about people with disabilities, sharing joyful moments and everyday challenges without shying away from the family's heartbreaking losses.

http://movies.netflix.com/WiMovie/My_Flesh_and_Blood/60032556?trkid=2361637

My Flesh and Blood is available on Netflix instant watch