Serendip is an independent site partnering with faculty at multiple colleges and universities around the world. Happy exploring!

Notes Towards Day 14 (Thurs, Oct. 25) : Exploring the campus geologically....

This faulted shale-limestone block, from the allochthonous Hamburg Sequence, south of Hamburg, Pa., is a product of the Late Ordovician (ca. 458 millions years ago), and commemorates the founding of the Department of Geology, Bryn Mawr College, by Florence Bascom, Ph.D., in 1895.

I. Coursekeeping

by 5 p.m. on Fri, your 7th writing assignment is due: 3 pp. reflecting on the ways in which your sense of Bryn Mawr has expanded in space and/or time. In what ways is your understanding of the campus shifting? Has your understanding of the need for (or the practice of) ecological literacy begun to alter in any way? (Remember: make a claim, give evidence to back it up, and construct an "opening" conclusion that reflects on the implications of the argument you've developed....) Send this to me and to your new writing partner:

Barbara <-> mbackus

Rochelle <-> Zoe

Susan <-> Sara L

Cahier <-> Hannah

mtran <-> Sarah C

Shengjia <-> wanhong

CMJ <-> alex

by 5 p.m. Sun: continue posting your descriptions of your on-campus site; how might the experiences you are having there be altered by our historical and geological explorations? Since we are 1/2-way through the semester, you could move location, if you'd like (go off campus, as per wanhong's suggestion: make your own field trip!), though I'd recommend your staying @ that site for the remainder of the semester.

by classtime on Tuesday, read Charlene Spretnak's 1987 explanation of ecofeminism. It sets its own context very clearly, offers a response to some of the questions we raised on Tuesday about how to teach environmental studies w/out succumbing to despair, raises another whole series of questions about the realtionship of gender and the environment, and invites us to think about interconnected oppressions. It's an early emergence of the environmental justice movement, which views the environment as encompassing "where we live, work, and play," and seeks to redress inequitable distributions of environmental burdens (pollution, industrial facilities, and crime....). Also bring back your copies of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring--we're not done w/ her!

Sara L will choose our location for Tuesday--here?

II. today, Maria Luisa Crawford will lead us on a campus-wide exploration of the

geological structures that undergird our current linguistic and cultural explorations.

50+ years ago, Prof. Crawford was a BMC undergrad; after

getting her Ph.D. @ Berkeley, taught geology here for over 40 years.....

since her research has focused on mountain belts that are 110 million years old,

I think she's going to enlarge our sense of time/elongate our sense of BMC's history...!

[Anne's notes, then Prof. Crawford's slides and notes follow....]

"I look down…what is the landscape like?

What around here is the result of that?

What do I see? Why is it there?

How can I explain that?

What do I need to know?"

The buildings here are made of very local rocks (or those quarried 70 miles away).

(What happened to the quarries? they are now water reservoirs, landfills...)

What rocks will stand up over time?

(look @ the gravestones: which will dissolve?

granite is best: very hard, and available;

the local rock is very resistant, but harder to carve;

you do NOT want to choose marble or limestone for your tombstones:

the more acid the rain, the easier it dissolves..)

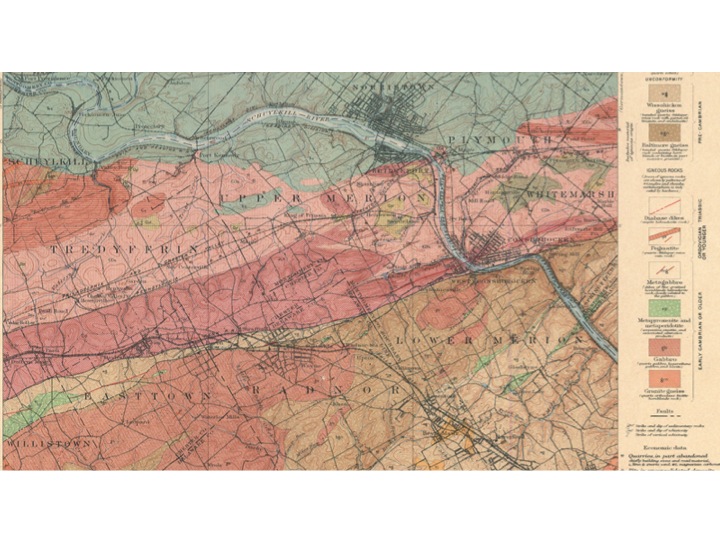

this colored map was made in the late 1880's by Florence Bascomb

(one of the first female geology Ph.D's in the U.S,

hired by the chemistry department to teach a geology course here,

she created both an undergraduate and graduate program in geology

and mapped a 5-mile corridor as long as from here to San Francisco

her geologic map shows different rocks, and draws lines between them:

each "package" of rocks is of a different age--the blue 250 million years old;

the red/brown rocks are older than 450 million years ago;

deeply buried as a huge mountain belt, then heated and transformed

there has been much wearing away since: we have just a few hills here now, no mountains

our typography reflects these rocks

limstone is the most easily dissolved, and forms valleys (such as the valley near Conshohocken)

the "blue" rocks on the map are hardened mud and sand,

similarly erodable, and create generally fairly rolling terrain

running unequally across the surface of the land, water always carves a valley,

and the deepest carvings become a stream valley

this map shows the drop off from harder to softer rock,

from that which is harder to remove to the mud and sand which becomes the lowland/coastal plain

this is a very important concept in the develoment of the eastern U.S.

since you can't sail a ship up the rapids....

the fall line (where all the streams run off the harder rock onto the coastal plain)

is where all the cities are located

"doodily, doodily, doodily....bonk!"

"every city is where it is because of the fall line"

we are elevated 320 ft. above sea level; a rise of 300' is predicted

advice to future homeowners: put yourself in a protected place (atop a hill!)

the pond below Rhodes was created in the 70s,

when the college built the new science building and computer center

we made a deal w/ the township to dam the water

running off from the hill @ the train station, and thereby create Rhodes pond;

the runoff from the pond then travels in pipes under the hockey field down to Mill Creek

(and eventually into the Schuylkill River)

this is a trade-off for the additional run-off we generated,

by paving new, larger parking lots around the science building

the Mill Creek historical district was an industrial site

the first mill was built in 1690 by a Welseh Quaker, John Roberts

it was a "grist" (grain kernels, w/ the outside removed) mill

a lot of mills were set up along this creek,

including flour and paper mills (early currency was printed on the paper produced here)

it was such a good source of energy because it had a 250 ft. drop off

there was always water in it (because this is a rainy climate)

because the creek was always flowing, the mills could always run;

there were very few days without a constant flow

this is very energy efficient: you don't pay for energy if its water driven!

the first dam was built in 1750, to create what is now Dove Lake

(which is now totally full/silted up)

there are a few remains of mills and millers houses,

but the flood of 1893 destroyed most of these mills

one woolen mill continued operating until the 1900s

in the late 18th century huge estate houses began to be built on high points

Tayor Hall was built on the highest point of the campus (it was safer!)

and so the landscape changed from an industrial to a wealthy suburban enclave,

used first as a summer retreat (the main building of the Baldwin School,

across the street, was a hotel run by the Pennsylvania Railroad);

many servants' houses were built in the middle of Bryn Mawr

(go wondering in town and you will note the smaller size)

the steepness of the alley determines how much flooding there is

the topography is too gentle for us to actually see the rock formations in this area

the corner of the playing field would have been a striking one, but

"people don't appreciate rocks," and so planted over the area, covering them up

then we went out to look @ what the buildings were made of:

Denbigh was built out of

Wissahickon (place where it is abundant)

Schist (type of rock, w/ mica in it, created by heat and pressure, forms sheets)

(the result of a deal Florence Bascomb made w/ her former professors at Johns Hopkins:

she traded "Wissahickon Schist" for "Baltimore Gneiss")

Merion (like Taylor Hall) is made out of Baltimore Gneiss

(you can see larger individual grains in the rock)

this came from quarries north of here;

we don't stand on this rock, but it occurs about 2 blocks away

it's made by the same heat and pressure, but hotter,

which changes the surface of the chemically unstable grains;

gneiss has "more things in it": quartz and feldspar (=decomposed mica)

Erdman is the only campus building made of slate

(which is tougher, but not harder, than schist or gneiss)

Campus Center, like Denbigh, is Wissahickon Schist

along the steps going down to the science center,

you can see iron oxide in a red/rusty rock (sedimentary siltstone)

Park Science Center was built in the 1930s (no local rock here!)

Moon Bench is built of granite, and won't wear away

@ the base of the gym we noted rocks with smaller grains and no obvious layers:

they are limestone, quarried near Conshocken, and are softer and cheaper,

used here to accomodate run-off/stop erosion

just before Batten House (which is probably built of Baltimore Gneiss--but it's painted over!)

we turned right to examine piles of

slate (w/ holes in it, used as roofing material; it splits easily)

white squares of granite,

Wissahickon Schist,

and large sheets of sandstone (which is mostly quartz, harder than mica, and often splits)

we also examined a fake rock (used to disguise a satellite dish?)

an abandoned fireplace (Baltimore Gneiss, with sandstone atop)

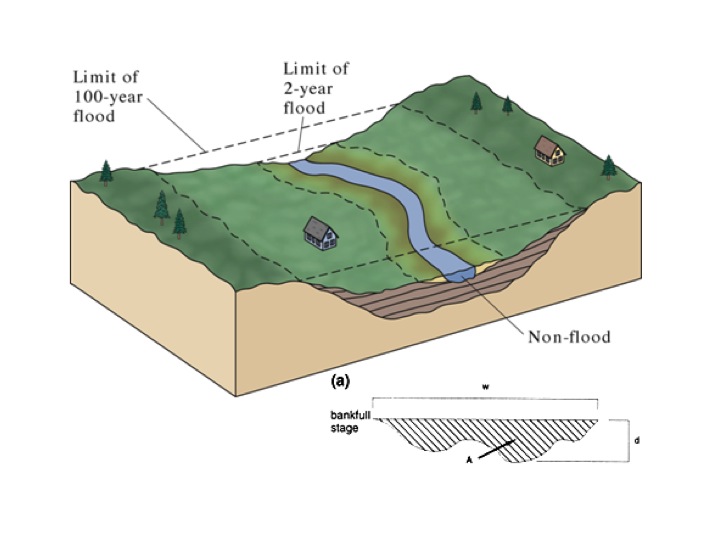

and then ....a sudden flatness! the floodplain for Mill Creek:

mud and sand are transported here whenever it floods

heavier material "falls out first," and gets deposited closer to the creek;

lighter material is further afield (where it's muddier and puddles-->

never build or buy on a flood plain, no matter how pretty!)

the creek meanders downstream to Dove Lake, creating natural levies,

deposting material on one side, causing erosion on the other,

cutting itself off, then straighening out again

(google "Mississippi River" to study this process),

we returned by way of Brecon, which is made of concrete, w/ some stones inset

Additional Notes---->

Mill Creek has its source in Villanova, runs southeast through Bryn Mawr, links with a tributary just east of Ardmore. There it turns sharply eastward and with new tributaries eventually empties into the Schuylkill at Flat Rock Park.

It flows down a heavily wooded ravine, under nineteenth century stone bridges, over paved fords, and through eighteenth and early nineteenth century mill settlements before finally meeting the Schuylkill River. It remains the best preserved mill stream along the southern Schuylkill River and one of the best in southeastern Pennsylvania.

It contains a landscape that has a rural historic characteristic yet is surrounded by suburban Philadelphia.

— all in a wooded setting along Mill Creek. This cluster of houses and mills is typical of mill villages of the 18th and early 19th century.

They were dispersed along the length of Mill Creek as it falls approximately 250 feet between the point of its origin south west of the boundary increase and the Schuylkill River.

Mill Creek had plenty of fall to turn mill wheels, and there were very few days during the year when there was not a constant flow of water. John Roberts I set up the first mill where there was a natural 10-12 foot head or fall of water. Many of the subsequent mills on the creek were set up in an area where there were either no natural fall, or falls not large enough to turn a wheel. In these areas, the millers did one of several things: they either built a dam and artificially raised the level of the creek, or they used a flume to carry the water to the top of their wheel.

Due to the narrowness of the creek gorge, the mill ponds tended to be small but deep, providing more than sufficient power to the mills. There are no surviving mill ponds along Mill Creek within the Mill Creek Historic District boundary increase.

The power of the water had devastating effects when uncontrolled. Storms and floods frequently destroyed dams and mills, wiping out the businesses. The flood of 1893 brought the final destruction of most remaining mills on the creek with one exception – the formed Nippes gun factory converted to the Barker Woolen Mill. Produced woolen thread into the 1950s.

The building material used in this district is locally quarried stone.

Mill buildings and mill workers' housing are located along the banks of the creek and in the ravines of its important tributaries. Large estate homes are mainly located on the hilltops.

MILL CREEK

The area was originally settled by a Welsh Quaker named John Roberts "the miller" who purchased the rights to 500 acres of land in the Welsh Tract in 1682. Taking title to 250 acres; he set up his grist mill called "The Wain" by 1690 or earlier.

John Roberts the Miller's grist mill which started here by 1690 was the beginning of an important milling industry which spread along Mill Creek until it eventually included up to twenty-three mills. These were in operation until a flood in 1893 virtually destroyed the industry.

The Mill Creek Historic District is significant because it played a major part in the genesis of industrial development of Lower Merion and, indirectly, of Philadelphia as well.

Mill Creek was easily dammed for water power. It was also well-situated in the eighteenth century for water traffic to Philadelphia. Moreover, there were early land routes to the Merion and Upper Gulph Mills areas and to fording places on the Schuylkill River.

By the mid-1700's it was discovered that the clear water and 250 foot fall of Mill Creek were perfect for the manufacture of fine hand-make white paper. In a cultural drift from Germantown, Whitemarsh and Roxborough (all on the opposite side of the Schuylkill), several families of German paper makers established mills on Mill Creek. The earliest of these was that of Conrad Sheetz (Shultz) of Germantown who bought David Davis' fulling mill in 1748 and began a paper mill.

Sheetz' "upper mill" was located at what is now Dove Lake. After Sheetz' death, his son-in-law George Helmbold(t) sold the "upper mill" to Thomas Amies (Amos) of Philadelphia in 1798. The mill was then called the "Dove Mill" and its dove-and-olive branch trademark were widely known. Here paper was manufactured for the Second Bank of the U.S. The "upper mill" site disappeared when Dove Lake was impounded in 1873.

After George McClenahan's death in 1833, his wife, Mary, inherited all of his 378 acres, save a small section with a paper mill which he had sold previously (not in district). In 1844, Mary sold ten acres, a factory and two frame tenements to Samuel Croft. The following years she sold an additional piece of land to him, giving Croft a total of thirty-five acres. Here, in 1846 (date-stone on pillar on Mill Creek Road), Croft established a brass and copper rolling mill called "the Croft-Kettle Mill." Croft rolled silver and copper for the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia (see John Levering's 1851 Map). This mill was in use throughout most of the second half of the nineteenth century.

Thus, the milling industry which began in the Mill Creek Historic District c.1690 continued for over two hundred years and was an important factor in the settlement and economic growth of the area.

---------------------------------------

Architecturally, it is significant for its large body of surviving eighteenth and nineteenth century mill complex resources, its group of large turn-of-the-century estate houses, and for the residential buildings designed and constructed in the nineteen twenties, thirties and forties by a locally prominent and nationally influential architect

Twentieth Century Contributing Estate Buildings

The highland areas are dotted with early twentieth century country estate buildings and structures designed in an eclectic and diverse group of revivalist styles. The estates are indicative of the transition between early industrial beginnings and to what became a wealthy suburban enclave. Wealthy individuals who wanted well-built homes carefully sited in scenic, natural settings.

The most striking attribute of the area encompassed by the Mill Creek Historic District Boundary Increase is the degree to which the eighteenth and nineteenth century rural landscape remains intact.

The fall line marks the geologic boundary of hard metamorphosed terrain – product of the Taconic orogeny – and the sandy, relatively flat outwash plain of the upper continental shelf formed of unconsolidated K and Tertiary sediments. Other examples the Great Falls of the Potomac river and the rapids in Richmond, VA where the James river fall across a series of rapids to the tidal estuary of the James River

Baltimore Gneiss ("granite" in construction language): Pennsylvania

Taylor

Brecon, 1905

Cartref, 1885

Merion, c. 1879

Wissahickon Schist:

Marie Salant Neuberger Centennial Campus Center, 1907-9, 1983 from Media Quarry (500 Beatty Rd, Springfield, Pennsylvania) or Chestnut Hill Quarry, Pennsylvania or Mermaid Quarry, 7811 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia?

Denbigh, Pembroke, Rhoads, Radnor, Thomas

Pennsylvania slate:

Eleanor Donnelley Erdman Hall, 1960-1965